Village Survey Monograph 28. Sunnambukulam Part VI Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Ancient Goddess Temple in South India

ANCIENT GODDESS TEMPLE IN SOUTH INDIA By Robert Scheer I had to stretch my neck to look up at the enormous tower. Nine stories tall, the gopuram was alive with colourfully painted, sculpted gods, goddesses and animals, soaring above the entrance to one of the largest and most unusual Hindu temples in South India. The Meenakshi Sundareswarar temple in Madurai attracts 10,000 visitors on a slow day, 25,000 on Fridays, and even more during a festival. I was there on a Friday evening during the Navaratri festival, and I felt grateful to have met a local who agreed to show me around. We left our shoes and socks at the gatehouse and walked past stalls selling garlands of fresh flowers—bright orange marigolds and red and yellow flowers that looked like chrysanthemums. The temple was busy, but it wasn’t as crowded as I feared it might be. Covering an area greater than fourteen acres, it can comfortably hold thousands of people, as well as at least one elephant. There was so much activity going on that it took me a moment to realize I was face to face with a live elephant. She had white spirals and floral patterns painted on her head, ears and trunk, and bells around her neck. I held out a 20 rupee note and she whisked it out of my hand. Suddenly her trunk was pressed against my forehead, nearly knocking off my eyeglasses; I had been blessed by a sacred elephant. Mr. Siva told me that the temple was unusual because its primary deity is not the god Shiva (known locally as Sundareswarar) but the goddess Meenakshi (another name for Shakti). -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

Tamil Nadu Highway Department, Salem Division. K.K Thangamuthu

Company Name(mandatory) Company Sector(mandatory) Incorporation Status(mandatory) Discipline(mandatory) Level(mandatory) Date From (mandatory) No of students(mandatory) Date To(mandatory) BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LIMITED (A Government of India Undertaking) BOILER AUXILIARIES PLANT, Indira Gandhi Industrial Complex RANIPET – 632 406 Energy Government Body Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 5/20/2019 1 5/25/2019 Tamil Nadu Public Work Department, Madurai. Engineering Government Body Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 5/27/2019 1 6/10/2019 Falcon Reality & Construction Pvt Ltd #16, 1st floor, race view colony 3rd street, maduvinkarai, Guindy,Chennai – 600 032 Engineering Private Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 5/23/2019 1 6/24/2019 Balamurugan Associates 87, GH road, EB office basement floor, Gobichettipalayam – 638 452 Engineering Private Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 12/3/2019 1 12/13/2019 Ranm Mala Builders, Appakoodal, Erode – 638 057 Engineering Private Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 25/12/2019 12 12/31/2019 Swifterz solutions, #100, 2nd Floor, Ramanuja Nagar, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641015 Engineering Private Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 12/1/2019 8 3/20/2020 Tamil Nadu Highway Department, Salem Division. Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 11/25/2018 7 12/18/2018 Thangavel Builders, S K Nagar, Pm Nagar, Seelanaickenpatti, Salem, Tamil Nadu 636006 Engineering Private Civil Engineering and Allied Degree 12/1/2018 6 12/9/2018 V.K.P Engineering India Pvt Ltd, Perundurai, Tamil Nadu 638052 Engineering Private Civil -

Chendrachoodeshwarar Temple Tank, Hosur-Tamil Nadu

SURFACE WATER WONDER: CHENDRACHOODESHWARAR TEMPLE TANK, HOSUR-TAMIL NADU M.ALAGURAJ Assistant Professor, Er.Perumal Manimekali College of Engineering, E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract - Temple tanks of south India are ancient water bodies that are integral components of temples. These tanks are a manifestation of a cultural sensitivity to water that is given a godly status within Hindu philosophy. Tanks are important for the sustainability of the environment and the economy of the village they serve. Temple tanks are the vital link in the water system and cater to the community scale of use, while the irrigation tanks cater to agriculture and the wells cater to domestic use. They harvest and store rainwater that is used for direct consumption through the year. However, their most important and often unnoticed function is providing percolation points with in the precincts of inhabitation of a town. Designed for recharging groundwater, they maintain the aquifer balance. The loss of this important environmental contribution is how being felt with urban tanks going dry. Temple tanks cater to various cultural, ritual, community and utilitarian functions. The connected temple tank of Chandrachoodeshwarar temple of Hosur exemplify this system. This traditional system gives us clues on how to improve our unsustainable urban water management mechanisms. I. INTRODUCTION of the tank. Fish consume algae which would otherwise turn the water coldly. Water has played a central role in Indian religious Curing several diseases- some pilgrims dip in ritual and as a result many places worship have water these water to cure their diseases. bodies associated with them. The temple tanks are Some of the tanks are significant either on account of revered no less than the temple itself. -

JSS 049 2D Parvatithampi Te

TEMPLES OF SOUTH INDIA by CjJaruati 73hampi Untouched by the architectural concepts of the West, un moved by Islamic influence, relatively undisturbed by the various invasions which the rest of India was periodically subject to, the temples of South India are some of the purest examples of Hindu and Dravidian art existing today. These buildings are no monarch's appeasement of his own vanity. Nor are they memorials to the dead. Nor again are they a more commemoration of one particular event. Rather are they testaments to Man's timeless faith in something or someone beyond himself. In fact these massive structures surging upwards and encompassing all the manifold aspects of Hindu reli gion and mythology are symbols of humanity's eternal reaching out to the sublime, the divine, the infinite. And whereas most well known architectural monuments are things of the past, wrapped in the silence of the dead, these temples today are still teeming with life and with a vitality all their own. The heyday of the South Indian temples lasted from the 7th to the 17th century, a.d.-from the reign of the Pallavas to the Vija yanagar and Nayyak dynasties. However, from references to them in the Puranas such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana, in the early Dravidian annals and in the works oE Tamil, Telugu, Malayalee and Canarese poets and scholars, the origin of this temple art dates back many hundreds of years before that, even to pre-Aryan times. Such a reference in a very early Dravidian work is made to the temple of Kanya Kumari at the extreme southern tip of India where the three oceans meet. -

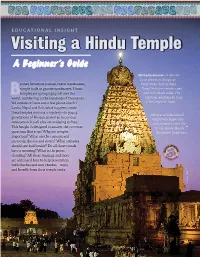

Visiting a Hindu Temple

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT Visiting a Hindu Temple A Beginner’s Guide Brihadeeswarar: A massive stone temple in Thanjavur, e they luxurious palaces, rustic warehouses, Tamil Nadu, built by Raja simple halls or granite sanctuaries, Hindu Raja Chola ten centuries ago B temples are springing up all over the and still vibrant today. The world, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. capstone, weighing 80 tons, Yet outside of India and a few places like Sri is the largest in India. Lanka, Nepal and Bali, what happens inside these temples remains a mystery—to young This special Educational generations of Hindus as well as to curious Insight was inspired by newcomers. It’s all a bit intimidating at first. and produced expressly This Insight is designed to answer the common for the Hindu Mandir questions that arise: Why are temples Executives’ Conference important? What are the customs and protocols, the dos and don’ts? What attitudes should one hold inside? Do all those rituals ATI O C N U A D have a meaning? What is the priest L E chanting? All these musings and more I N S S T are addressed here to help newcomers— I G H both Hindus and non-Hindus—enjoy and benefit from their temple visits. dinodia.com Quick Start… Dress modestly, no shorts or short skirts. Remove shoes before entering. Be respectful of God and the Gods. Bring your problems, prayers or sorrows but leave food and improper manners outside. Do not enter the shrines without invitation or sit with your feet pointing toward the Deities or another person. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

Temple Structure

DR. JYOTI PRABHA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY M.R.M. COLLEGE, L.N.M.U., DARBHANGA 2ND SEMESTER, SESSION: 2019-21 CC- 8: SOCIETY AND ECONOMY IN INDIAN HISTORY UNIT- 2: ART AND ARCHITECTURE Temple Structure Most of the art and architectural remains that survive from Ancient and Medieval India are religious in nature. That does not mean that people did not have art in their homes at those times, but domestic dwellings and the things in them were mostly made from materials like wood and clay which have perished. This chapter introduces us to many types of temples from India. Although we have focused mostly on Hindu temples, at the end of the chapter you will find some information on major Buddhist and Jain temples too. However, at all times, we must keep in mind that religious shrines were also made for many local cults in villages and forest areas, but again, not being of stone the ancient or medieval shrines in those areas have also vanished. Temple Architecture Gupta period marks the beginning of Indian temple architecture. Manuals were written regarding how to form temples. The Gupta temples were of five main types: 1) Square building with flat roof shallow pillared porch; as Kankali Devi temple at Tigawa and the Vishnu Varaha temples at Eran. The nucleus of a temple – the sanctum or cella (garbhagriha) – with a single entrance and apporch (Mandapa) appears for the first time here. 2) An elaboration of the first type with the addition of an ambulatory (paradakshina) around the sanctum sometimes a second storey; examples the Shiva temple at Bhumara(M.P.) and the lad-khan at Aihole. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Hon'ble Judges

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS Reserved on : 20..01..2016 Delivered on : 05..07..2016 CORAM The Hon'ble Mr. SANJAY KISHAN KAUL, CHIEF JUSTICE and The Honourable Mrs. Justice PUSHPA SATHYANARAYANA Writ Petition Nos.1215 and 20372 of 2015 and Criminal Original Petition Nos.7086 and 7153 of 2015 W.P. No.1215 of 2015 1. S. Tamilselvan 2. Perumal Murugan … Petitioners (R-2 impleaded as per order dated 24.02.2015 in M.P. No.2 of 2015 in W.P. No.1215 of 2015) Versus 1. The Government of Tamil Nadu, Rep. by the Secretary, Home Department, Fort St. George, Chennai 600 009. 2. The District Collector, Namakkal. 3. The District Revenue Officer Tiruchencode, Namakkal District. 4. The Deputy Superintendent of Police Tiruchencode, Namakkal District. 5. Pon. Govindarasu, Arulmigu Arthanaareeswarar Girivala Nala Sangam, No.36, Anjaneyar Koil Street, Tiruchengode Taluk, Namakkal District. P a g e | 2 6. K. Chinnusamy, Hindu Munnani Office, Door No.74/34, Anjaneyar Koil Street, Tiruchengode, Namakkal District. 7. Kandasamy, President, Morur Kannakula Kongu Nattu Vellalar Trust, Morur Village & Post, Sangagiri Taluk, Salem District-637 304. 8. M. Madesh, President, Sengunthar Mahajana Sangam, No.9-H, B. Komarapalayam, Namakkal District. 9. P.T. Rajamanickam, General Secretary, Federation of Kongu Vellalar Sangam, Kongu Kalai Arangam, No.34, Sampath Nagar, Erode-11. 10. Mahalingam, President, Hindu Munnani, Tiruchengode Taluk, Namakkal District. 11. Yuvaraj, President, Dheeran Chinnamalai Peravai, Sangagiri, Salem District. 12. Anitha Velu, President, Lorry Owners Association, Tiruchengode, Namakkal District. 13. Muthusamy, T.V.A.N. Jewellery, President, Vaniga Peravai, Tiruchengode, Namakkal District. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2014 [Price: Rs. 26.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 43] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2014 Aippasi 26, Jaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2045 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 13313-3378 Notice .. 3378 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 57699. I, Mohamed Fathima, wife of Thiru Kaja Mohideen, 57702. I, Chinnapparaj, son of Thiru Shanmugavel, born on born on 17th August 1978 (native district: Tirunelveli), 7th April 1966 (native district: Coimbatore), residing at Old residing at No. 27, Moolan Ahamed Pillai Street, No. 82-139, New No. 19-203, S.O. Tempower House Loyar Melapalayam, Tirunelveli-627 005, shall henceforth be Camp, Solaiyar Nagar, Valparai Taluk, Coimbatore-642 125, known as SYED ALI FATHIMA. shall henceforth be known as S. RAJ. ºý‹ñ¶ ð£ˆFñ£. CHINNAPPARAJ. Melapalayam, 3rd November 2014. Valparai, 3rd November 2014. 57700. I, Jansi, wife of Thiru Stephen Esurajan, born on 57703. I, J. Alagu, wife of Thiru P. Jeevanandham, born on 14th October 1953 (native district: Madurai), residing at 6th April 1971 (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 115/30A, Vaithiyanadha puram West Lane, Madurai- Old No. 23, New No. 2/103, West Street, Agraharam, 625 016, shall henceforth be known as S.