Reading Between Blurred Lines: the Complexity of Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

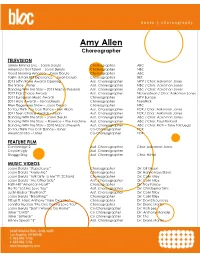

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

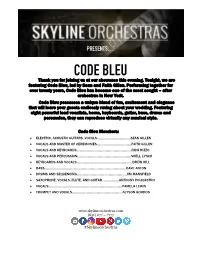

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Hollywood Stars Nicole Kidman, Uma Thurman and Andy Garcia As

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 09/20/2019 2:38:30 PM PRINCE ALBERT II OF MONACO /W\ FOUNDATION Hollywood Stars Nicole Kidman, Uma Thurman and Andy Garcia as Masters of Ceremony; Robert Redford as Honoree; Gwen Stefani, Andrea Bocelli, Robin Thicke and Kool and the Gang as Performers; and Many More International Stars are Joining Forces with HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco to Save the Ocean and Fight Climate Change Impressive List of International Stars to Attend and Perform at the Third Annual Monte-Carlo Gala for the Global Ocean in Support of Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation Initiatives to Protect the Global Ocean September 20, 2019 (Monte-Carlo) - The Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, the world leading Foundation for the protection of the Global Ocean and the Planet’s Environment, today revealed the impressive list of international artists and superstars who will join HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco on September 26, 2019, at the third Monte-Carlo Gala for the Global Ocean, which is the world’s biggest charity fundraiser of today. “Above all, the Ocean is a vital component for our global balance. It represents 97% of its biosphere. It is host to the majority of living species, produces most of the oxygen we breathe, regulates our climate and generates 60% of the ecosystem services which enable us to live. Sadly, however, the Ocean is also symbol of our irresponsibility. It suffers all the damage we inflict on our planet.” said HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco. “That’s why this year’s Gala for the Global Ocean in Monte-Carlo is so important. -

In the Thicke of It Jessie M

SURGE Center for Public Service 9-2-2013 In The Thicke Of It Jessie M. Pierce Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Pierce, Jessie M., "In The Thicke Of It" (2013). SURGE. 84. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge/84 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge/84 This open access blog post is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In The Thicke Of It Abstract If you’ve been anywhere near your Facebook newsfeed in the last few days, you’re probably familiar with the most recent images of Miley Cyrus at her less-than-graceful VMA performance. From CNN’s front page headline, “What Was Miley Thinking?” to Buzzfeed’s gifset of a cartoon Cyrus twerking on famous paintings, her antics have, for better or for worse, become a hyper-inflated mega-sensation that I, frankly, don’t care about at all. I’m not going to talk about Miley anymore. Instead, let’s talk about her co-performer, Robin Thicke. [excerpt] Keywords Surge, Surge Gettysburg, Gettysburg College, Center for Public Service, VMA awards, Miley Cyrus, Robin Thicke, rape culture Disciplines American Popular Culture | Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence | Gender and Sexuality Comments Surge is a student blog at Gettysburg College where systemic issues of justice matter. -

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography official website COMMERCIALS (partial list) Verizon, Workday ft. Naomi Osaka, IBM, M&Ms, *Beats by Dre, Absolut, Chase, Kellogg’s, Google, Ellen Beauty, Instagram, AT&T, Apple, Adidas, Gap, Old Navy, Bumble, P&G, eBay, Amazon Prime, **Netflix “A Great Day in Hollywood”, Nivea, Spectrum, YouTube, Checkers, Lexus, Dobel, Comcast XFinity, Captain Morgan, ***Nike, Marriott, Chevrolet, Sky Vodka, Cadillac, UNCF, Union Bank, 02, Juicy Couture, Tacori Jewelry, Samsung, Asahi Beer, Duracell, Weight Watchers, Gillette, Timberland, Uniqlo, Lee Jeans, Abreva, GMC, Grey Goose, EA Sports, Kia, Harley Davidson, Gatorade, Burlington, Sunsilk, Versus, Kose, Escada, Mennen, Dolce & Gabbana, Citizen Watches, Aruba Tourism, Texas Instruments, Sunlight, Cover Girl, Clairol, Coppertone, GMC, Reebok, Dockers, Dasani, Smirnoff Ice, Big Red, Budweiser, Nintendo, Jenny Craig, Wild Turkey, Tommy Hilfiger, Fuji, Almay, Anti-Smoking PSA, Sony, Canon, Levi’s, Jaguar, Pepsi, Sears, Coke, Avon, American Express, Snapple, Polaroid, Oxford Insurance, Liberty Mutual, ESPN, Yamaha, Nissan, Miller Lite, Pantene, LG *2021 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial – Beats by Dre “You Love Me” **2019 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial ***2017 D&AD Professional Awards Winner – Cinematography for Film Advertising – Nike “Equality” MUSIC VIDEOS (partial list) Arianna Grande, Miley Cyrus & Lana Del Rey, Kanye West feat. Nicki Minaj & Ty Dolla $ign, N.E.R.D. & Rihanna, Jay Z, Charli XCX, Damian Marley, *Beyoncé, Kanye West, Nate Ruess, Kendrick Lamar, Sia, Nicole Scherzinger, Arcade Fire, Bruno Mars, The Weekend, Selena Gomez, **Lana Del Rey, Mariah Carey, Nicki Minaj, Drake, Ciara, Usher, Rihanna, Will I Am, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J, Black Eyed Peas, Pharrell, Robin Thicke, Ricky Martin, Lauryn Hill, Nas, Ziggy Marley, Youssou N’Dour, Jennifer Lopez, Michael Jackson, Mary J. -

Smr Td Resume 2011

FILM | TELEVISION MUSIC VIDEOS PRODUCTION DESIGNER PRODUCTION DESIGNER Disney XD • Zero Displacement • Director: Pat Notaro DUFFY • Keeping the Baby • Director: Petro Pappa • DRAW PICTURES Babylon Beach • Infidelis Productions • Director: Eric Bergemann FRANKI LOVE • Shadows • Director: Bryan Robbins • DI POST Red Weather • ABC | Disney • Director : Jordan Downey (Pre - Production) • Super Duper Love • Director: David LaChapelle • HSI JOSS STONE Small Town News (pilot) • STN LLC • Directors : Holt Bailey & Eric Steele PLACEBO • Follow the ... • Director: Daniel Askill • RADICAL MEDIA Lost • SILVERCREST FILM • Director: Darren Lemke • Producer : Ralph Winter THRICE • Come All You... • Director : Zach Merck • RADICAL MEDIA Down South • BEDFORD FILMS • Director : Hank Bedford SWITCHFOOT • Oh! Gravity • Director: P.R. Brown • RADICAL MEDIA Emergency • EMERGENCY LLC • Director : Jordan Downey Way of the Tiger • THE MINE • Director: Chris Salzgeber TRANSPLANTS • What I Can’t... • Director: Estevan Oriol • HSI THE BRAVERY • Fearless • Director: Diane Martel • DNA THE ACADEMY IS • The Phrase...• Director: Marvin Jarrett • TOYSTORE ART DIRECTOR • [2nd Unit / Pick-Ups] SHANE M. RICHARDSON Harold and Kumar... • SENATOR FILMS • Director : Danny leiner VHS OR BETA • You Got Me • Director: Ryan Rickett • REFUSED TV [email protected] LIMBECK • People Don’t Change • Director: Ryan Rickett • REFUSED TV SET DECORATOR | PROPMASTER KARRI KIMMEL • Not Make Believe • Director: Garreth O’Neil • DISNEY www.tandemdesign.biz Jingles (reality gameshow) • MARK -

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

RICHARD BUSCH the Man, Whose Wife Was the Copyright Administra- Force Majeure Provisions in Contracts

“ I COME FROM A FIRM THAT DOESN’T HAVE CONNECTIONS AT THE RECORD LABELS. WHEN PEOPLE COME TO ME, THEY KNOW THEY HAVE 100% OF MY LOYALTY.” What is it like being a litigator in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic? It’s a challenge. Hearings are either being ruled on based on the submitted papers or after a telephonic 1 hearing. I like to think my papers are pretty persua- sive, but clients want you in the room, in person. When you go to a courtroom, you can read the room lead sheet, to get it on file with the Copyright Office. and take signals from the judge’s questions. What they are saying by that decision is that Marvin Depositions over Zoom create their own obstacles. Gaye is no longer the composer of “Got To Give It Part of the purpose of a deposition is to be right there Up” — that rather some unknown person hired to with the witness. Now you don’t know what’s going do a lead sheet to get a copyright registration is the on behind the scenes, what’s going on during the author. It’s absurd! I believe the Supreme Court, if it breaks. It’s just not an effective process. Unfortunate- looked at the issue, would conclude that the Ninth ly, I think this is going to continue for most of 2020, Circuit was absolutely wrong. and when we get back into the courtrooms there is going to be a bottleneck of cases. In your lawsuit against Spotify brought by Eminem’s publisher Eight Mile Style, you have called the The pandemic has hit the music industry hard, espe- Music Modernization Act “unconstitutional.” Why Busch photographed cially the live business. -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

12 BM~~~R~~~F5tftr{Ilfution 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 CENTRAL DISTRICT of CALIFORNIA, WESTERN DIVISION

Case 2:13-cv-06004-JAK-AGR Document 385 Filed 05/11/15 Page 1 of 38 Page ID #:11528 1 KING, HOLMES, PATERNO & BERLINER, LLP HOWARD E. KING, ESQ., STATE BARNO. 77012 2 STEPHEN D. ROTHSCHILD, ESQ., STATE BARNO. 132514 [email protected] 3 SETHMILLER,ESQ., STATEBARNO. 175130 [email protected] 4 1900 A VENUE OF THE STARS, 25TH FLOOR Los ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90067-4506 5 TELEPHONE: (31 0) 282-8989 FACSIMILE: (31 0) 282-8903 6 Attorneys for Plaintiffs and Counter- 7 Defendants PHARRELL WILLIAMS, ROBIN THICKE and CLIFFORD 8 HARRIS, JR. and Counter-Defendants MORE WATER FROM NAZARETH 9 PUBLISHING, INC., PAULA MAXINE PATTON individ}l~ly and d/b/a 10 HADDINGTON MUSIC, STAR TRAK ENTERT~NT GEFFEN 11 RECORDS, INTERSCOPE RECORDS, 12 BM~~~R~~~f5tftr{ilfuTION 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA, WESTERN DIVISION 15 PHARRELL WILLIAMS, an CASE NO. CV13-06004-JAK ~AGRx) individual; ROBIN THICKE, an Hon. John A. Kronstadt, Ctrm 50 16 individua~ and CLIFFORD HARRIS, JR., an in ividual, CORRECTED NOTICE OF 17 MOTION AND MOTION OF Plaintiffs, PHARRELL WILLIAMS, ROBIN 18 THICKE AND MORE WATER vs. FROM NAZARETH PUBLISHING, 19 INC. FOR JUDGMENT AS A BRIDGEPORT MUSIC INC., a MATTER OF LAW, 20 Michi§an CODJoration; FRAN:KiE DECLARATORY RELIEF, A NEW CHRI TIAN GAYE, an individual; TRIAL, OR REMITTITUR; 21 MARVIN GAYE lib an individual; NONA MARVISA AYE, an MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND 22 individual; and DOES 1 through 10, AUTHORITIES inclusive, 23 Date: June 29, 2015 Defendants. Time: 8:30a.m. 24 Ctrm.: 750 25 AND RELATED COUNTERCLAIMS. -

Jemel Mcwilliams Resume

jemel mcwilliams choreographer selected credits contact: (818) 509-0121 LIVE STAGING / TOURS LIZZO “Cuz I Love Your” Tour ’19 Choreographer Big GRRRL Janelle Monáe – Lollapalooza / Osheaga Festival Choreographer Tuxedo Touring LLC John Legend - Hollywood Bowl Choreographer John Legend Touring Inc. LIZZO Coachella ‘19 Co-Creative/Choreographer Big GRRRL Janelle Monáe Coachella ‘19 Artistic Dir./Choreographer Wondaland Records John Legend “A Legendary Christmas” Tour ’18 Choreographer Sony Music John Legend iHeartRadio Live ’18 Choreographer Sony Music Janelle Monáe “Dirty Computer” World Tour ’18 Artistic Dir./Choreographer Wondaland Records Janelle Monáe - Mempho Festival ’18 Artistic Dir./Choreographer Wondaland Records Janelle Monáe - Made in America ’18 Artistic Dir./Choreographer TIDAL John Legend “Darkness and Light” World Tour ’17-’18 Choreographer/Movement Coach Live Nation Tours The Boy Band Promo Tour ’16 Creative Director/Choreographer RCA Records BET Awards Jidenna Pre-Show Performance ’16 Choreographer BET MAGIC! (Maroon 5 opener) World Tour ’15 Choreographer/Movement Coach RCA Records Shontelle Promo Tour ’11 Choreographer Republic Records Alicia Keys “Set the World on Fire” Tour Assoc. Artistic Dir./Assoc. Choreographer Sony Music Robin Thicke “Blurred Lines” Tour Assoc. Choreographer Interscope TELEVISION / COMMERCIAL American Music Awards ‘19 – LIZZO “Jerome” Choreographer ABC The Today Show – John Legend “Bring Me Love” Choreographer NBC UK Celebrity X-Factor – LIZZO “Good As Hell” Choreographer FOX The Ellen DeGeneres -

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 2018 This List Is Compiled Based on Over 2 Million Song Requests Made Using the DJ Event Planner Song Request System

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs In 2018 This list is compiled based on over 2 million song requests made using the DJ Event Planner song request system. Rank Artist Song Title 1 Killers Mr. Brightside 2 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 3 Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 4 Bon Jov i Livin' On A Prayer 5 ABBA Dancing Queen 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 8 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 9 Pharrell Williams Happy 10 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 11 Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 12 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 13 Luis Fonsi feat. Daddy Yankee Despacito 14 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 15 Queen Don't Stop Me Now 16 Bruno Mars Marry You 17 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline 18 Oasis Wonderwall 19 Toploader Dancing In The Moonlight 20 Beyonce feat. Jay-Z Crazy In Love 21 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 22 Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 23 Rihanna feat. Calv in Harris We Found Love 24 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 25 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-go 26 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 27 Ed Sheeran Shape Of You 28 Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse Valerie 29 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 30 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 31 Cyndi Lauper Girls Just Want To Have Fun 32 John Trav olta & Oliv ia Newton-John Grease Megamix 33 R. Kelly Ignition (Remix) 34 September 34 Earth, Wind and Fire September 35 B-52's Love Shack 36 Los Del Rio Macarena 37 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 38 Kenny Loggins Footloose 39 Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger 40 Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life 41 Stev ie Wonder Superstition 42 Creedence Clearwater Rev iv al / Tina Turner Proud Mary 43 Snap! Rhythm Is A Dancer 44 Usher Yeah! 45 Spice Girls Wannabe 46 OutKast Hey Ya! 47 Robin S Show Me Love 48 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 49 House Of Pain Jump Around 50 Beatles Twist And Shout 51 Village People Y.M.C.A.