Stealing Shahbag: a Re-Legitimization of Islamism in the Aftermath of a Secularist Social Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

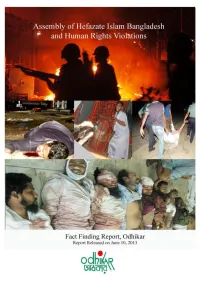

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Internal Communication Clearance Form

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT DES NATIONS UNIES OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PROCEDURES SPECIALES DU SPECIAL PROCEDURES OF THE CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L’HOMME HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Mandates of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression and the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. REFERENCE: UA G/SO 214 (67-17) G/SO 214 (53-24) G/SO 218/2 BGD 6/2013 30 April 2013 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacity as Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression and pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 15/18, 16/23, and 16/4. In this connection, we would like to draw the attention of your Excellency’s Government to information we have received regarding the alledged torture and ill- treatment of Mr. Mahmudur Rahman while in police custody and the alledged sealing and closure of the printing press of the Bangladeshi newspaper Amar Desh. According to the information received: On 11 April 2013, Mr. Mahmudur Rahman, the interim Editor of the Bangladeshi newspaper Amar Desh (Daily Amardesh) and human rights defender, was arrested at his office. It is reported that since that day, the Government has sealed and closed the newspaper’s printing press. -

Daily Star Weekend Magazine (SWM) in February 9, 2007

Interview Freethinkers of Our Time For over the last one and a half decades Mukto-Mona has been fighting for the development of humanism and freethinking in South Asia. The organisation's member-contributor's included novelist Humayun Azad. In an email conversation with the SWM, three members of mukto-mona.com talk about the state of freedom in Bangladesh, and South Asia in general. Ahmede Hussain 1. How has Mukto-Mona evolved? Can you please explain the idea behind Mukto-Mona for our readers? Avijit Roy: Mukto-Mona came into being in the year 2000, with the intention of debating and promoting critical issues that are of the utmost importance in building a progressive, rational and secular society, but usually are ignored in the man stream Bangladeshi and South Asian media. For example, consider the question: Does one need to adhere to a religious doctrine to live an honest, decent and fulfilled life? This may seem like an off-the-track topic to many, but at the same, we cannot deny that this is a very critical and crucial question. It was 2000. I was very active on the net and writing in several e-forums simultaneously on topics pertaining to rationalism, humanism and science. One such e-forum which I came across at that time was News From Bangladesh (NFB) which regularly published debates between believers and rationalists like me. Although only a handful in number, I discovered, I was not alone. I met a few more expatriate Bangladeshi writers (of whom some constitute today Mukto-Mona’s advisory and editorial board) who also thought in same way about religious doctrine and conventional beliefs. -

Bangladesh's Failed Election

April 2014, Volume 25, Number 2 $13.00 Democratic Parliamentary Monarchies Alfred Stepan, Juan J. Linz, and Juli F. Minoves Ethnic Power-Sharing and Democracy Donald L. Horowitz Nelson Mandela’s Legacy Princeton N. Lyman The Freedom House Survey for 2013 Arch Puddington A New Twilight in Zimbabwe? Adrienne LeBas Charles Mangongera Shifting Tides in South Asia Sumit Ganguly Maya Tudor Ali Riaz Mahendra Lawoti Jason Stone S.D. Muni Fathima Musthaq Shifting Tides in South Asia BANGLADESH’S FAILED ELECTION Ali Riaz Ali Riaz is professor of politics and government at Illinois State Univer- sity. In 2013, he was a Public Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson In- ternational Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. His books include Political Islam and Governance in Bangladesh (2010). Is democracy in Bangladesh undergoing a reversal? This question must be asked in the wake of the country’s troubled tenth parliamentary elec- tion, which took place on 5 January 2014. Boycotted by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the rest of the opposition, the voting was marred by the lowest turnout and worst electoral violence in Bangla- desh’s 43-year history.1 The result is a Parliament in which the incum- bent Awami League (AL) and its allies control nearly all 300 elected seats.2 Owing to the boycott, more than half the races—or 154, to be exact—featured but a single candidate. Before the polls opened, BNP leader Khaleda Zia (who served as prime minister in 1991–96 and 2001–2006) had been placed under vir- tual house arrest while Jatiya Party (JP) head H.M. -

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

Amnesty International Public Statement

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC STATEMENT AI index: ASA 13/003/2013 22 February 2013 Bangladesh: Resist pressure to push for hasty death sentences at war crimes Tribunal Amnesty International is concerned that the government of Bangladesh may use new amendments to the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act 1973 (ICT Act) to push for hasty death sentences to be imposed on individuals convicted by Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT). The amendments, passed by Parliament on 17 February, permit the prosecution to appeal against any decision of the ICT to impose a lesser sentence. The ICT is a national court established in 2010 to try people suspected of crimes under international law, including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, committed during Bangladesh’s 1971 war of independence. The ICT Act governs the conduct of trials before the ICT. After opening its first trial in November 2011, the ICT delivered its first verdict – in absentia - on 21 January 2013. Abul Kalam Azad, associated with the opposition religious party Jamaat- e-Islami, was convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death. On 5 February, the ICT delivered its second judgment and sentenced Abdul Quader Molla, a senior member of the same opposition party, to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. Following that second verdict, members of the ruling Awami League government claimed that the sentence was not enough and that a death sentence should have been handed down. At the same time, a large-scale protest movement has erupted in Dhaka, demanding the death sentence for Abdul Quader Molla and any others convicted of crimes under international law by the ICT. -

Mapping the Body-Politic of the Raped Woman and the Nation in Bangladesh

gendered embodiments: mapping the body-politic of the raped woman and the nation in Bangladesh Mookherjee, Nayanika . Feminist Review, suppl. War 88 (Apr 2008): 36-53. Turn on hit highlighting for speaking browsers Turn off hit highlighting Other formats: Citation/Abstract Full text - PDF (206 KB) Abstract (summary) Translate There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation. Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts. This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. I show the ways in which the visual representation of this 'motherland' as fertile countryside, and its idealization primarily through rural landscapes has enabled a crystallization of essentialist gender roles for women. This article is particularly interested in how these images had to be reconciled with the subjectivities of women raped during the Bangladesh Liberation War (Muktijuddho) and the role of the aestheticizing sensibilities of Bangladesh's middle class in that process. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT] Show less Full Text Translate Turn on search term navigation introduction There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation (Yuval-Davis and Anthias, 1989; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Yuval-Davis and Werbner, 1999). Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts (Kandiyoti, 1991; Chatterjee, 1994). This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. -

Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein1 to Taslima Nasrin

ASIATIC, VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2016 From Islamic Feminism to Radical Feminism: Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein1 to Taslima Nasrin Niaz Zaman2 Independent University, Bangladesh Abstract This paper examines four women writers who have contributed through their writings and actions to the awakening of women in Bangladesh: Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein, Sufia Kamal, Jahanara Imam and Taslima Nasrin. The first three succeeded in making a space for themselves in the Bangladesh tradition and carved a special niche in Bangladesh. All three of them were writers in different genres – poetry, prose, fiction – with the last best known for her diary about 1971. While these iconic figures contributed towards women’s empowerment or people’s rights in general, Taslima Nasrin is the most radically feminist of the group. However, while her voice largely echoes in the voices of young Bangladeshi women today – often unacknowledged – she has been shunned by her own country. The paper attempts to explain why, while other women writers have also said what Taslima Nasrin has, she alone is ostracised. Keywords Islamic feminism, radical feminism, gynocritics, purdah, 1971, Shahbagh protests In this paper, I wish to examine four women writers who have contributed through their writings and actions to the awakening of women in Bangladesh. Beginning with Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein (1880-1932), I will also discuss the roles played by Sufia Kamal (1911-99), Jahanara Imam (1929-94) and Taslima Nasrin (1962-). The first three succeeded in making a space for themselves in the Bangladesh tradition and carved a special niche in Bangladesh. All three of them were writers: Roquiah wrote poems, short stories, a novel, as well as prose pieces; Sufia Kamal was primarily a poet but also wrote a number of short 1 There is some confusion over the spelling of her name. -

Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Monday 26 May 2014

Bangladesh - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on Monday 26 May 2014 Information on the activities of Taliban & Muslim extremists including interaction with society In May 2014 a publication released by Jane’s Intelligence Review notes that: “Bangladesh faces growing security threats from a range of radical Islamist interests, including entrenched Deobandi militants, newly emergent jihadist groups, and even transnational operations such as Al-Qaeda” (Jane’s Intelligence Review (1 May 2014) Radical thinking - Transnational jihadists eye Bangladesh). This report also notes: “A message from Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in January 2014, the first specifically directed at Bangladesh, will resonate with a number of radical groups aiming to spread jihad within the country. Despite not having established a cell within Bangladesh to date, Al-Qaeda's apparently rising interest in the country will galvanise local groups that pose a more immediate security threat. Bangladesh, the fourth largest Muslim majority country in the world, has experienced resurgent religious confrontations since 2013, with moderate and radical Islamist forces taking to the streets for intermittently violent confrontations that have undermined the country's secular credentials…Within this troubled atmosphere, latent Islamist militancy also exists in the form of well-entrenched Deobandi militant groups such as Jamaat ul- Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) and Harakat-ul-Jihad-ul-Islami-Bangladesh (HUJI-B), both of which can trace their lineage to JeI and are now attempting to regain some of their past influence. Other newly founded militant Islamist groups, such as the Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT), are also finding the resources and opportunities to mark their presence on the Jihadist landscape of Bangladesh. -

Merchant/Company Name

Merchant/Company Name Zone Name Outlet Address A R LADIES FASHION HOUSE Adabor Shamoli Square Shopping Mall Level#3,Shop No#341, ,Dhaka-1207 ADIL GENERAL STORE Adabor HOUSE# 5 ROAD # 4,, SHEKHERTEK, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Archies Adabor Shop no:142,Ground Floor,Japan city Garden,Tokyo square,, Mohammadpur,Dhaka-1207. Archies Gallery Adabor TOKYO SQUARE JAPAN GARDEN CITY, SHOP#155 (GROUND FLOOR) TAJ MAHAL ROAD,RING ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR DHAKA-1207 Asma & Zara Toy Shop Adabor TOKIYO SQUARE, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, LEVEL-1, SHOP-148 BAG GALLARY Adabor SHOP# 427, LEVEL # 4, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING MALL, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, BARCODE Adabor HOUSE- 82, ROAD- 3, MOHAMMADPUR HOUSING SOCIETY, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BARCODE Adabor SHOP-51, 1ST FLOOR, SHIMANTO SHOMVAR, DHANMONDI, DHAKA-1205 BISMILLAH TRADING CORPORATION Adabor SHOP#312-313(2ND FLOOR),SHYAMOLI SQUARE, MIRPUR ROAD,DHAKA-1207. Black & White Adabor 34/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor 32/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor HOUSE-41, ROAD-2, BLOCK-B, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor 15/10, TAJMAHAL ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor EST-02, BAFWAA SHOPPING COMPLEX, BAF SHAHEEN COLLEGE, MOHAKHALI BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-08, URBAN VOID, KA-9/1,. BASHUNDHARA ROAD BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-33, BLOCK-C, LEVEL-08, BASHUNDHARA CITY SHOPPING COMPLEX CASUAL PARK Adabor SHOP NO # 280/281,BLOCK # C LEVEL- 2 SHAYMOLI SQUARE COSMETICS WORLD Adabor TOKYO SQUARE,SHOP#139(G,FLOOR)JAPAN GARDEN CITY,24/A,TAJMOHOL ROAD(RING ROAD), BLOCK#C, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 DAZZLE Adabor SHOP#532, LEVEL-5, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING COMPLEX, JAPAN GARDEN CITY (RING ROAD) MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207. -

1 Introduction

210 Notes Notes 1Introduction 1 See Taj I. Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, in H. Mutalib and T.I. Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State, pp. 100–34. 2The Government of Bangladesh, The Constitution of the People’s Repub- lic of Bangladesh, Section 28 (1 & 2), Government Printing Press, Dhaka, 1990, p. 19. 3See Coordinating Council for Human Rights in Bangladesh, (CCHRB) Bangladesh: State of Human Rights, 1992, CCHRB, Dhaka; Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence Against Women, Institute of Democratic Rights, Dhaka, 1991; US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Prac- tices for 1992, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1993; Rushdie Begum et al., Nari Nirjatan: Sangya O Bishleshon (Bengali), Narigrantha Prabartana, Dhaka, 1992, passim. 4 CCHRB Report, 1993, p. 69. 5 Immigration and Refugee Board (Canada), Report, ‘Women in Bangla- desh’, Human Rights Briefs, Ottawa, 1993, pp. 8–9. 6Ibid, pp. 9–10. 7 The Daily Star, 18 January 1998. 8Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence, pp. 14–15. 9 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 20. 10 Taj Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, p. 117. 11 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 6. 12 Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid, ‘Women, Islam, and the State: Subordination and Resistance’, paper presented at the Bengal Studies Conference (28–30 April 1995), Chicago, pp. 1–2. 13 Ibid, pp. 4–5. 14 U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, ‘Jamaat-i-Islami in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects’, in Hussin Mutalib and Taj Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslim and the Modern State, pp. 86–93. 15 Lynne Brydon and Sylvia Chant, Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas, p. -

2 Crowd Violence in East Pakistan/ Bangladesh 1971–1972

Christian Gerlach 2 Crowd Violence in East Pakistan/ Bangladesh 1971–1972 Introduction Some recent scholarship links violent persecutions in the 20th century to the rise of mass political participation.1 This paper substantiates this claim by exploring part of a country’s history of crowd violence. Such acts constitute a specific form of participation in collective violence and shaping it. There are others such as forming local militias, small informal violent gangs or a guerrilla, calls for vio- lence in petitions or non-violent demonstrations and also acting through a state apparatus, meaning that functionaries contribute personal ideas and perceptions to the action of a bureaucracy in some persecution. Therefore it seems to make sense to investigate specific qualities of participation in crowd violence. Subject to this inquiry is violence against humans by large groups of civilians, with no regard to other collectives of military or paramilitary groups, as large as they may have been. My approach to this topic is informed by my interest in what I call “ex- tremely violent societies.” This means social formations in which, for some pe- riod, various population groups become victims of mass violence in which, alongside state organs, many members of several social groups participate for a variety of reasons.2 Aside from the participatory character of violence, this is also about its multiple target groups and sometimes its multipolar character. Applied here, this means to compare the different degrees to which crowd vio- lence was used by and against different groups and why. It is evident that the line between perpetrators and bystanders is especially blurred within violent crowds.