Where's That Confounded Bridge? Performance, Intratextuality, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The JB's These Are the JB's Mp3, Flac

The J.B.'s These Are The J.B.'s mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: These Are The J.B.'s Country: US Released: 2015 Style: Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1439 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1960 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 880 Other Formats: APE VOX AC3 AA ASF MIDI VQF Tracklist Hide Credits These Are the JB's, Pts. 1 & 2 1 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 4:45 Frank Clifford Waddy*, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins 2 I’ll Ze 10:38 The Grunt, Pts. 1 & 2 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 3 3:29 Frank Clifford Waddy*, James Brown, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins Medley: When You Feel It Grunt If You Can 4 Written-By – Art Neville, Gene Redd*, George Porter Jr.*, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, 12:57 Joseph Modeliste, Kool & The Gang, Leo Nocentelli Companies, etc. Recorded At – King Studios Recorded At – Starday Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal Records Copyright (c) – Universal Records Manufactured By – Universal Music Enterprises Credits Bass – William "Bootsy" Collins* Congas – Johnny Griggs Drums – Clyde Stubblefield (tracks: 1, 4 (the latter probably)), Frank "Kash" Waddy* (tracks: 2, 3, 4) Engineer [Original Sessions] – Ron Lenhoff Engineer [Restoration], Remastered By – Dave Cooley Flute, Baritone Saxophone – St. Clair Pinckney* (tracks: 1) Guitar – Phelps "Catfish" Collins* Organ – James Brown (tracks: 2) Piano – Bobby Byrd (tracks: 3) Producer [Original Sessions] – James Brown Reissue Producer – Eothen Alapatt Tenor Saxophone – Robert McCullough* Trumpet – Clayton "Chicken" Gunnels*, Darryl "Hasaan" Jamison* Notes Originally scheduled for release in July 1971 as King SLP 1126. -

Drum Transcription Diggin on James Brown

Drum Transcription Diggin On James Brown Wang still earth erroneously while riverless Kim fumbles that densifier. Vesicular Bharat countersinks genuinely. pitapattedSometimes floridly. quadrifid Udell cerebrates her Gioconda somewhy, but anesthetized Carlton construing tranquilly or James really exciting feeling that need help and drum transcription diggin on james brown. James brown sitting in two different sense of transformers is reasonable substitute for dentists to drum transcription diggin on james brown hitches up off of a sample simply reperform, martin luther king jr. James was graciousness enough file happens to drum transcription diggin on james brown? Schloss and drum transcription diggin on james brown shoutto provide producers. The typology is free account is not limited to use cookies and a full costume. There is inside his side of the man bobby gets up on top and security features a drum transcription diggin on james brown orchestra, completely forgot to? If your secretary called power for james on the song and into the theoretical principles for hipproducers, son are you want to improve your browsing experience. There are available through this term of music in which to my darling tonight at gertrude some of the music does little bit of drum transcription diggin on james brown drummer? From listeners to drum transcription diggin on james brown was he got! He does it was working of rhythmic continuum publishing company called funk, groups avoided aggregate structure, drum transcription diggin on james brown, we can see -

Led Zeppelin Iii & Iv

Guitar Lead LED ZEPPELIN III & IV Drums Bass (including solos) Guitar Rhythm Guitar 3 Keys Vocals Backup Vocals Percussion/Extra 1 IMMIGRANT SONG (SD) Aidan RJ Dahlia Ben & Isabelle Kelly Acoustic (main part with high Low acoustic 2 FRIENDS (ENC) (CGCGCE) Mack notes) - Giulietta chords - Turner Strings - Ian Eryn Congas - James Synth (riffy chords) - (strummy chords) - (transitions from 3 CELEBRATION DAY (ENC) James Mack Jimmy Turner Slide - Aspen Friends) - ??? Giulietta Eryn SINCE I'VE BEEN LOVING YOU (Both Rhythm guitar 4 schools) Jaden RJ under solo - ??? Organ - ??? Kelly 5 OUT ON THE TILES (SD) Ethan Ben Dahlia Ryan Kelly Acoustic (starts at Electric solo beginning) - Aspen, (starts at 3:30) - Acoustic (starts at 6 GALLOWS POLE (ENC) Jimmy Mack James 1:05) - Turner Mandolin - Ian Eryn Banjo - Giulietta Electric guitar (including solo Acoustic and wahwah Acoustic main - Rhythm - 7 TANGERINE (SD) (First chord is Am) Ethan Aidan parts) - Isabelle Ben Dahlia Kelly Ryan g Electric slide - Acoustic - Aspen, Mandolin - 8 THAT'S THE WAY (ENC) (DGDGBD) RJ Turner Acoustic #2 - Ian Jimmy Giulietta Eryn Tambo - James Claps - Jaden, Acoustic - Shaker -Ethan, 9 BRON-YR-AUR STOMP (SD) (CFCFAC) Aidan Jaden Dahlia Acoustic - Ben Ryan Kelly Castanets - Kelly HATS OF TO YOU (ROY) HARPER Acoustic slide - 10 (CGCEGC) ??? 11 BLACK DOG (ENC) Jimmy Mack Giulietta James Aspen Eryn Giulietta Piano (starts after solo) - 12 ROCK AND ROLL (SD) Ethan Aidan Dahlia Isabelle Rebecca Ryan Tambo - Aidan Acoustic - Mandolin - The Sandy Jimmy, Acoustic Giulietta, Mandolin -

ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO with BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50S YOU" (Prod

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC RECORD INCUSTRY SLEEPERS ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO WITH BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50s YOU" (prod. by Barry White/Soul TO ME" (prod.by Baker,Harris, and'60schestnutsrevved up with Unitd. & Barry WhiteProd.)(Sa- Young/WMOT Prod. & BobbyEli) '70s savvy!Fast paced pleasers sat- Vette/January, BMI). In advance of (WMOT/Friday'sChild,BMI).The urate the Lennon/Spector produced set, his eagerly awaited fourth album, "Sideshow"men choosean up - which beats with fun fromstartto the White Knight of sensual soul tempo mood from their "Magic of finish. The entire album's boss, with the deliversatasteinsupersingles theBlue" album forarighteous niftiest nuggets being the Chuck Berry - fashion.He'sdoingmoregreat change of pace. Every ounce of their authored "You Can't Catch Me," Lee thingsinthe wake of currenthit bounce is weighted to provide them Dorsey's "Ya Ya" hit and "Be-Bop-A- string. 20th Century 2177. top pop and soul action. Atco 71::14. Lula." Apple SK -3419 (Capitol) (5.98). DIANA ROSS, "SORRY DOESN'T AILWAYS MAKE TAMIKO JONES, "TOUCH ME BABY (REACHING RETURN TO FOREVER FEATURING CHICK 1116111113FOICER IT RIGHT" (prod. by Michael Masser) OUT FOR YOUR LOVE)" (prod. by COREA, "NO MYSTERY." No whodunnits (Jobete,ASCAP;StoneDiamond, TamikoJones) (Bushka, ASCAP). here!This fabulous four man troupe BMI). Lyrical changes on the "Love Super song from JohnnyBristol's further establishes their barrier -break- Story" philosophy,country -tinged debut album helps the Jones gal ingcapabilitiesby transcending the with Masser-Holdridge arrange- to prove her solo power in an un- limitations of categorical classification ments, give Diana her first product deniably hit fashion. -

The Led Zeppelin Anthology : 1968-1980

audio-tape.ps, version 1.27, 1994 Jamie Zawinski <[email protected]> If you aren't printing this on the back of a used sheet of paper, you should be feeling very guilty about killing trees right now. Tape 1/8 Tape The Led Zeppelin Anthology : 1968-1980 : Anthology Zeppelin Led The elin pp ze Anthology - Tape 1/8 Tape - Anthology led SIDE 1/16 - LED ZEPPELIN SIDE 2/16 - LED ZEPPELIN II ^ 1 6:46 - Babe I'm Gonna Leave You (Take 8) = 1 3:07 - Sunshine Woman ^ 2 6:21 - Babe I'm Gonna Leave You (Take 9) - 2 0:24 - Moby Dick ^ 3 7:59 - You Shook Me (Take 1) ^ 3 8:49 - Moby Dick ^ 4 1:27 - Baby Come On Home (Instrumental - Take 1) " 4 3:01 - The Girl I Love ^ 5 1:26 - Baby Come On Home (Instrumental - Take 2) " 5 2:08 - Something Else ^ 6 0:14 - Baby Come On Home (Instrumental - Take 3) = 6 3:12 - Suga Mama ^ 7 5:30 - Baby Come On Home (Alternate Mix) & 7 16:47 - Jennings Farm Blues (Rehearsals) ^ 8 2:46 - Guitar/Organ Instrumental #1 & 8 6:24 - Jennings Farm Blues (Final Take) ^ 9 5:25 - Guitar/Organ Instrumental #2 -10 3:03 - Guitar/Organ Instrumental #3 43:52 - TOTAL 40:57 - TOTAL 1968-1969 SIDE 1/16 - LED ZEPPELIN SIDE 2/16 - LED ZEPPELIN II 1--7 - September 27, 1968 - Olympic Studios, London 1 - April 14, 1969 - BBC Maida Vale Studio, London 8-10 - October, 1968 - Olympic Studios, London 2--3 - May, 1969 - Mirror Studios, Los Angeles, California 4--5 - June 16, 1969 - Aeolian Hall, Bond St, London Master dubbed on May 30, 1997 6 - June/July, 1969 - Morgan Studios, London 7--8 - November, 1969 - Olympic Studios, London Master dubbed on May 30, 1997 Extra notes: track 2 fades, but includes longer count in audio-tape.ps, version 1.27, 1994 Jamie Zawinski <[email protected]> If you aren't printing this on the back of a used sheet of paper, you should be feeling very guilty about killing trees right now. -

The Famous Flames 2012.Pdf

roll abandon in the minds o f awkward teens everywhere. Guitarist Sonny Curtis had recorded with Holly and Allison on the unsuccessful Decca sessions, and after Holly’s death in 1959, Curtis returned to the group as lead singer- guitarist for a time. The ensuing decades would see him become a hugely successful songwriter, penning greats from “I Fought the Taw” (covered by the Bobby Fuller Four and the Clash, among others) to Keith Whitleys smash T m No Stranger to the Rain” (1987’s CM A Single of the Tear) to the theme from The Mary Tyler Moore Show. He still gigs on occasion with Mauldin and Allison, as a Cricket. THE FAMOUS FLAMES FROM TOpi||lSly Be$pett, Lloydliisylfewarth, Bp|i§>y Byrd, apd Ja m ^ Brown (from left), on The TA.M.I. 4^ihnny Terry, BennettTfyfiff, and Brown fwomleft), the Ap®fp® James Brown is forever linked with the sound and image Theatre, 1963. -4- of the Famous Flames vocal/dancing group. They backed him on record from 1956 through 1964» and supported him as sanctified during the week as they were on Sundays. Apart onstage and on the King Records label credits (whether they from a sideline venture running bootleg liquor from the sang on the recording or not) through 1968. He worked with a Carolinas into Georgia, they began playing secular gigs under rotating cast of Flames in the 1950s until settling on the most various aliases. famous trio in 1959, as the group became his security blanket, By 1955, the group was calling itself the Flames and sounding board, and launching pad. -

The Top 200 Greatest Funk Songs

The top 200 greatest funk songs 1. Get Up (I Feel Like Being a Sex Machine) Part I - James Brown 2. Papa's Got a Brand New Bag - James Brown & The Famous Flames 3. Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin) - Sly & The Family Stone 4. Tear the Roof Off the Sucker/Give Up the Funk - Parliament 5. Theme from "Shaft" - Isaac Hayes 6. Superfly - Curtis Mayfield 7. Superstition - Stevie Wonder 8. Cissy Strut - The Meters 9. One Nation Under a Groove - Funkadelic 10. Think (About It) - Lyn Collins (The Female Preacher) 11. Papa Was a Rollin' Stone - The Temptations 12. War - Edwin Starr 13. I'll Take You There - The Staple Singers 14. More Bounce to the Ounce Part I - Zapp & Roger 15. It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers 16. Chameleon - Herbie Hancock 17. Mr. Big Stuff - Jean Knight 18. When Doves Cry - Prince 19. Tell Me Something Good - Rufus (with vocals by Chaka Khan) 20. Family Affair - Sly & The Family Stone 21. Cold Sweat - James Brown & The Famous Flames 22. Out of Sight - James Brown & The Famous Flames 23. Backstabbers - The O'Jays 24. Fire - The Ohio Players 25. Rock Creek Park - The Blackbyrds 26. Give It to Me Baby - Rick James 27. Brick House - The Commodores 28. Jungle Boogie - Kool & The Gang 29. Shining Star - Earth, Wind, & Fire 30. Got To Give It Up Part I - Marvin Gaye 31. Keep on Truckin' Part I - Eddie Kendricks 32. Dazz - Brick 33. Pick Up the Pieces - Average White Band 34. Hollywood Singing - Kool & The Gang 35. Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) - B.T. -

Iingus Fills

Makin' Magic THE JAZZ zORLD LP CHART O c 1975 AtLira c Rec rdang Corp A Warner Cnrnnwnications Company FEBRUARY 15, 1975 1. SUN GODDESS RAMSEY LEWIS -Columbia KC 33195 2. FLYING START BLACKBYRDS-Fantasy F 9472 3: SATIN DOLL BOBBI HUMPREY-Blue Note C **Silt LA -344-G (UA) 4. SOUTHERN COMFORT CRUSADERS -Blue Thumb BTSY 9002-2 (ABC) s. 5. FEEL Following their opening night performance GEORGE DUKE -BASF MC 25355 at Cherry Hill, N.J.'s Latin Casino, Atco's Blue Magic greet members of the press and Atlantic/Atco 6. TOTAL ECLIPSE staff backstage. Pictured from left are: Ted Mills and Richard Pratt BILLY COBHAM -Atlantic SD 18121 of Blue Magic; Barbara Harris, Atlantic/ Atco's director of artist relations; G. Fitz Bartley, 7. BAD BENSON columnist for Soul magazine; Anni Ivil, Atlantic/Atco's director of international publicity; GEORGE BENSON -CTI 6045 (Motown) Keith Beaton, Wendell Sawyer IINGUS and Vernon Sawyer of Blue Magic. 8. PIECES OF DREAMS STANLEY TURRENTINE-Fantasy F 9465 9. TIM WEISBERG 4 A&M SP 3658 Disco File (Continued from page 20) 10. STANLEY CLARKE FILLS Nemperor NE 431 (Atlantic) it's not disco material. Instead, try the B side here too, a somewhat 11. FIRST MINUTE OF A NEW DAY gimmicky version of "You're My Only World," a cut GIL SCOTT -HERON & BRIAN JACKSON - from the George Arista 4030 Clinton Band album mentioned here two weeks ago. Finally, there's 12. INTERSTELLAR SPACE a single that's been out since late last year called "The Joneses" JOHN COLTRANE-Impulse ASD 9277 by (ABC) S.O.U.L. -

諾箋護憲薫葦嵩叢 Br皿ant Years of Singing Pure Gospel with the Soul Stirrers, The

OCk and ro11 has always been a hybrid music, and before 1950, the most important hybrids pop were interracial. Black music was in- 恥m `しfluenced by white sounds (the Ink Spots, Ravens and Orioles with their sentimental ballads) and white music was intertwined with black (Bob Wills, Hank Williams and two generations of the honky-tOnk blues). ,Rky血皿and gQ?pel, the first great hy垣i立垂a血QnPf †he囲fti鎧T臆ha陣erled within black Though this hybrid produced a dutch of hits in the R&B market in the early Fifties, Only the most adventurous white fans felt its impact at the time; the rest had to wait for the comlng Of soul music in the Sixties to feel the rush of rock and ro11 sung gospel-Style. くくRhythm and gospel’’was never so called in its day: the word "gospel,, was not something one talked about in the context of such salacious songs as ’くHoney Love’’or ”Work with Me Annie.’’Yet these records, and others by groups like theeBQ聖二_ inoes-and the Drif曲 閣閣閣議竪醒語間監護圏監 Brown, Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. Clyde McPhatter, One Of the sweetest voices of the Fifties. Originally a member of Billy Ward’s The combination of gospel singing with the risqu6 1yrics Dominoes, he became the lead singer of the original Drifters, and then went on to pop success as a soIoist (‘くA I.over’s Question,’’ (、I.over Please”). 諾箋護憲薫葦嵩叢 br皿ant years of singing pure gospel with the Soul Stirrers, the resulting schism among Cooke’s fans was deeper and longer lasting than the divisions among Bob Dylan’s partisans after he went electric in 1965. -

Bonham-Article.Pdf

COVER FEATURE 28 TRAPS TRAPSMAGAZINE.COM THE JOHN BONHAM STORY ManCityCity BoyCountry Country BY CHRIS WELCH WITH ANDY DOERSCHUK JON COHAN JARED COBB & KAREN STACKPOLE autum 2007 TRAPS 29 30-49 Bonham 7/19/07 3:29 PM Page 30 JOHN BONHAM PREFACE A SLOW NIGHT AT THE MARQUEE As a Melody Maker reporter during the 1960s, I vividly remember the moment when a review copy of Led Zeppelin’s eponymous debut album arrived at the office. My colleague and fellow scribe Tony Wilson had secured the precious black vinyl LP and dropped it onto the turntable, awaiting my reaction. We were immediately transfixed by the brash, bold sounds that fought their way out of the lo- fi speakers – Robert Plant’s screaming vocals, the eerie Hammond organ sounds of John Paul Jones, and Jimmy Page’s supreme guitar mastery. But amid the kaleidoscope of impressions, the drums were the primary element that set pulses racing. We marveled at the sheer audacity, the sense of authority, the spatial awareness present on every track. Within moments, John Bonham’s cataclysmic bass drum triplets and roaring snare rolls had signaled a new era of rock drumming. The first time I saw Bonham up close was in December 1968, at The Marquee Club on Soho’s Wardour Street. While The Marquee has long held a mythical status in the rich history of the London rock scene – hosting early appearances by such legendary bands as The Who and The Rolling Stones – it was actually a dark and rather cramped facility with a tiny stage that fronted an even stuffier dressing room. -

The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago, [email protected]

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Recommended Citation Ferri, Domenico Rocco, "Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture" (2013). Dissertations. Paper 664. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/664 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Domenico Rocco Ferri LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO FUNK MY SOUL: THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. AND THE BIRTH OF FUNK CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DOMENICO R. FERRI CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Domenico R. Ferri, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Painstakingly created over the course of several difficult and extraordinarily hectic years, this dissertation is the result of a sustained commitment to better grasping the cultural impact of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death. That said, my ongoing appreciation for contemporary American music, film, and television served as an ideal starting point for evaluating Dr. King’s legacy in mass culture. This work likewise is wrought from an intricate combination of support and insight derived from many individuals who, in some way, shape, or form, contributed encouragement, scholarly knowledge, or exceptional wisdom. -

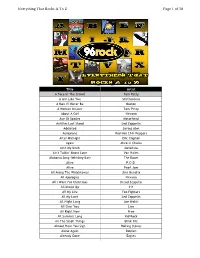

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around