Rhetoric and Reader Engagement in Rūmī's Mathnawī

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

Blasphemy, Charlie Hebdo, and the Freedom of Belief and Expression

Blasphemy, Charlie Hebdo, and the Freedom of Belief and Expression The Paris attacks and the reactions rashad ali The horrific events in Paris, with the killing of a group of Other reactions highlight and emphasise the fact journalists, a Police officer, and members of the Jewish that Muslims are also victims of terrorism – often the community in France have shocked and horrified most main victims – a point which Charlie Hebdo made in commentators. These atrocities, which the Yemen branch an editorial of the first issue of the magazine published of the global terrorist group al-Qaeda have claimed the following the attack on its staff. Still others highlight responsibility for,1 have led to condemnations from that Jews were targeted merely because they were Jews.2 across the political spectrum and across religious divides. This was even more relevant given how a BBC journalist Some ubiquitous slogans that have arisen, whether appeared to suggest that there was a connection between Je suis Charlie, Ahmed, or Juif, have been used to show how “Jews” treated Palestinians in Israel and the killing of empathy with various victims of these horrid events. Jews in France in a kosher shop.3 These different responses illustrate some of the divides in The most notorious response arguably has not come public reaction, with solidarity shown to various camps. from Islamist circles but from the French neo-fascist For example, some have wished to show support and comedian Dieudonne for stating on his Facebook solidarity with the victims but have not wished to imply account “je me sens Charlie Coulibaly” (“I feel like Charlie or show support to Charlie Hebdo as a publication, Coulibaly”). -

Identification of Urdu Ghazal Poets Using SVM

Mehran University Research Journal of Engineering & Technology Vol. 38, No. 4, 935-944 October 2019 p-ISSN: 0254-7821, e-ISSN: 2413-7219 DOI: 10.22581/muet1982.1904.07 Identification of Urdu Ghazal Poets using SVM NIDA TARIQ*, IQRA EJAZ*, MUHAMMAD KAMRAN MALIK*, ZUBAIR NAWAZ*, AND FAISAL BUKHARI* RECEIVED ON 08.06.2018 ACCEPTED ON 30.10.2018 ABSTRACT Urdu literature has a rich tradition of poetry, with many forms, one of which is Ghazal. Urdu poetry structures are mainly of Arabic origin. It has complex and different sentence structure compared to our daily language which makes it hard to classify. Our research is focused on the identification of poets if given with ghazals as input. Previously, no one has done this type of work. Two main factors which help categorize and classify a given text are the contents and writing style. Urdu poets like Mirza Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir, Iqbal and many others have a different writing style and the topic of interest. Our model caters these two factors, classify ghazals using different classification models such as SVM (Support Vector Machines), Decision Tree, Random forest, Naïve Bayes and KNN (K-Nearest Neighbors). Furthermore, we have also applied feature selection techniques like chi square model and L1 based feature selection. For experimentation, we have prepared a dataset of about 4000 Ghazals. We have also compared the accuracy of different classifiers and concluded the best results for the collected dataset of Ghazals. Key Words: Text classification, Support Vector Machines, Urdu poetry, Naïve Bayes, Decision Tree, Feature Selection, Chi Square, k-Nearest Neighbors, Ghazal, L1, Random Forest. -

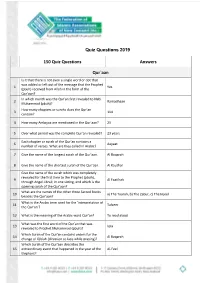

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

Durr-E-Sameen English Translation

Revised: December 19, 2008 m-dash corrected PRECIOUS PEARLS English translation of Durr-e Sameen (Urdu) By Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Translated by Waheed Ahmad Precious Pearls 3 Translation copyright 2008 by Waheed Ahmad All rights reserved Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Ahmad, Ghulam, 1835-1908 Precious Pearls: English translation of Durr-e Sameen First published in Urdu in 1896 ISBN 1. Ahmad, Waheed II. Title Printed by 4 LIST OF CONTENTS Page 1. Help of God 23 Nusrat-e Ilahi 2. Invitation to ponder 23 Da’wat-e fikr 3. Beneficence of the glorious Quran 23 Fazail-e Quran 4. Addressing the Christians 24 ‘Isaiyoon se khitaab 5. Excellences of the glorious Quran 25 Ausaaf Quran majeed 6. Praise to the Lord of the worlds 26 Hamd Rabbil ‘Alameen 7. The fleeting world 27 Sara-e khaam 8. The Vedas 27 Ved 9. Death of Jesus of Nazareth 28 Wafaat-e Masih Nasri 10. The Signs of near ones 29 ‘Alamaat-il muqarrabeen 11. A plea to God Almighty 29 Qadir Mutlaq ke hazoor 12. Love with Islam and its founder 30 Islam aur bani-e Islam se ‘ishq 13. The Cloak of Baba Nanak 31 Chola Baba Nanak 14. The fruit of Truth 42 Taseer-e sadaqat 15. Mahmood’s Ameen 42 Mahmood ki ameen 16. In the words of Amman Jaan 47 … ba zubaan-e Amman Jaan 17. The Mother of Books 48 Ummul Kitaab 18. Knowledge of God 49 Ma’arfat-e Haq 19. Basheer Ahmad’s Ameen 49 Basheer Ahmad … ki ameen 20. The status of Ahmad of Arabia 58 Shaan-e Ahmad-e ‘Arabi 21. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Urdu Ug Cbcs Syllabus-01.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF MYSORE DEPARTMENT OF STUDIES IN URDU MANASAGANGOTRI MYSORE-570 005 B.A Programme (Optionals) DSC – Discipline Specific Course (Core) Sem. Course Title of the paper L – T - P Total Credit I DSC - 1 Dastan aur Masnavi 5 – 1- 0 6 II DSC - 2 Novel aur Marsiya 5 – 1- 0 6 III DSC - 3 Drama aur Gazlein 5 – 1- 0 6 IV DSC - 4 Afsanay aur Manzomath 5 – 1- 0 6 DSE – Discipline Specific Elective (Soft Core) Sem. Course Title of the paper L – T - P Total Credit V DSE-1 1. Tareekh-e-Zaban-o- 5-1-0 6 Adab 2. Tanqeed Arooz-o- 5-1-0 6 Balagath 3. Special author Altaf Hussain Hali VI DSE-2 1. History of Urdu 5-1-0 6 literature 2. Urdu mein Khaka 5-1-0 6 Nigari 3. Urdu Afsana 5-1-0 6 GE – Generic Elective (Open Elective) Sem. Course Title of the paper L – T - P Total Credit V GE-1 1. Tarjuma Nigari 1-1-0 2 2. Urdu Sahafath VI GE-2 1. Iblag-e-Aamma 1-1-0 2 2. Computer -2- Urdu Syllabus under CBCS BA/B.SC Programme (Language) AECC – Ability Enhancement Compulsory Course (MIL) Language Sem. Course Title of the paper L – T - P Total Credit I AECC-1 Prose and Poetry 2-1-0 3 II AECC-2 Prose and Poetry 2-1-0 3 III AECC-3 Prose and Poetry 2-1-0 3 IV AECC-4 Drama and Poetry 2-1-0 3 SEC Skill Enhancement Course Sem. -

Hamd House Preparatory School Independent School Inspection Report

Hamd House Preparatory School Independent School Inspection report DfES registration number 330 6097 Unique reference number 131687 Inspection number 301531 Inspection dates 13–14 June 2007 Reporting inspector Dr Nasim Butt This inspection of the school was carried out under section 162A of the Education Act 2002 (as amended by schedule 8 of the Education Act 2005). Inspection of funded nursery education was carried out under Schedule 26 of the Schools Standards and Framework Act 1998. Inspection report: Hamd House Preparatory School, 13–14 June 2007 © Crown copyright 2007 Website: www.ofsted.gov.uk This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that the information quoted is reproduced without adaptation and the source and date of publication are stated. Inspection report: Hamd House Preparatory School, 13–14 June 2007 2 Purpose and scope of the inspection This inspection of the school was carried out by Ofsted under section 162A of the Education Act 2002, as amended by schedule 8 of the Education Act 2005, in order to advise the Secretary of State for Education and Skills about the school’s suitability for continued registration as an independent school. Information about the school Hamd House Preparatory School was established in 1998 and caters for pupils aged 3 to 11 years. It is situated in a refurbished, Victorian church in the Small Heath area of Birmingham. Funded nursery education is provided for children under five and over three years and is registered with Ofsted’s Children’s Directorate. This provision was inspected separately and is reported on at the end of this report. -

S. No. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders without / invalid CNIC # as of 31-12-2019 S. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address No. of No. Securities 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN S/O MR. MOHAMMAD WAZIR KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI S/O MR. MOHD ABDUL HAFEEZ 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3,280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN S/O MURTUZA MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD MR. HAMID HUSSAIN C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE S/O A. RAHIM B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9,382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED S/O GHULAM QADDIR KHAN H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN S/O MOHD NASRULLAH KHAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA S/O FAZAL-I-MAHMOOD 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1,919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN S/O ABDUR REHMAN KHAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8,530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN SARDAR M. FAROOQ IBRAHIM 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5,945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN S/O KH. -

2019-2020-Student Handbook

AIA Weekend Islamic School American Islamic Association 8860 W. St Francis Rd, Frankfort, IL 60423 Phone: (815) 469-1551 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.aiamasjid.org AIA Student Handbook – 2019-2020 Contents Page 3……. INTRODUCTION -- Open Letter to Parents Page 4……. Attendance Page 4……. Tardiness Page 4……. Security and Safety of Students Page 4……. Homework Page 4……. Class Supplies Page 4……. Weather Emergencies Page 4……. Emergency Drills Page 5……. Competitions Page 5……. Examinations Page 5……. Complaints and Questions Page 5……. Parents Involvement Page 5……. Dress Code Page 5……. Parent-Teacher Conferences Page 6……. Discipline Policy Page 7……. Students Classification Page 8……. Class Schedule Page 9……. Calendar of Events Page 10……. Syllabus Course Material – Kindergarten and Elementary Page 11……. Syllabus Course Material – Level 1 and Level 2 Page 12……. Syllabus Course Material – Level 3 and Level 4 Page 13……. Syllabus Course Material – Level 5, Level 6 and Level 7 Page 14……. Syllabus Course Material – Level 8, Level 9 and Level 10 Page 15……. Syllabus Course Material – Level 11 & Level 12 Effective 09/01/2019 Page 2 AIA Student Handbook – 2019-2020 In the Name of Allah, The Beneficent, The Most Merciful INTRODUCTION Dear Parents: Welcome to the new school year at the AIA Weekend Islamic School. We are committed to provide quality Islamic education and excellent services to your children. We are excited to build on our successes from the past by implementing what worked best for us and learning lessons from our mistakes. We are grateful to Allah (SWT) that we have a very competent and dedicated group of teachers who offer their services to the school despite constraints of their social and family obligations. -

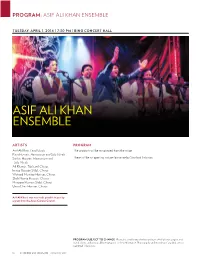

Asif Ali Khan Ensemble

PROGRAM: ASIF ALI KHAN ENSEMBLE T UESDAY, APRil 1, 2014 / 7:30 PM / BiNG CONCERT HALL ASIF ALI KHAN ENSEMBLE ARTISTS PROGRAM Asif Ali Khan, Lead Vocals The program will be announced from the stage. Raza Hussain, Harmonium and Solo Vocals Sarfraz Hussain, Harmonium and There will be an opening-act performance by Stanford Talisman. Solo Vocals Ali Khawar, Tabla and Chorus Imtiaz Hussain Shibli, Chorus Waheed Mumtaz Hussain, Chorus Shah Nawaz Hussain, Chorus Manzoor Hussain Shibli, Chorus Umar Draz Hussain, Chorus Asif Ali Khan’s tour was made possible in part by a grant from the Asian Cultural Council. PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE. Please be considerate of others and turn off all phones, pagers, and watch alarms, and unwrap all lozenges prior to the performance. Photography and recording of any kind are not permitted. Thank you. 14 STANFORD LIVE MAGAZINE APRIL/MAy 2014 PROGRAM: ASIF ALI KHAN ENSEMBLE PROGRAM NOTES a residency at the University of an end in itself, implying that the state It is the courage of each, it is the power Washington in 1992 that qawwali began of ecstasy is a manifestation of God. of flight, to be heard again in the United States outside the South Asian community. In Because the art of qawwali, as with Some fly and remain in the garden, 1993, a 13-city tour of North America most of the great Asian musical and some go beyond the stars. organized by the World Music Institute literary traditions, is transmitted cemented Nusrat’s reputation in the orally, the mystical verse associated —Amir Khusrau, 13th century United States and helped to build with qawwali is best appreciated by a far wider interest in qawwali.