The Nurse and the Mental Patient; a Study in Interpersonal Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Students Turn Into "Stars." Ces at 'D:45 P.M

U The Florida Alligator ci. 0, yJrl r p fri Albert The Original Returns From Exile Hootenanny Tonight Hootenanny! Tomorrow night, Jimmie Rodgers, Josh 'From the campus of the University of White and Family; the 'Tarriers, Hoyt Florida." Axton, Joan Myers and comedian Jackie It starts at 8 o'clock tonight as Florida Vernon will star. Gym becomes a TV studio and thousands Doors close for the evening performan- of U!' students turn into "stars." ces at 'd:45 p.m. both nights and at 4:45 One of the nationally-televised show's p.m. for the two afternoon dress reher- main features is the closeups of the stu- sals. - dent audiences it entertains all over the The original Albert the Alligator, UF's nation. mascot, was hauled here by truck from A few UJE-ers have already been caught his home at Ross Allen's Reptile Ranch on video t ape. Hundreds of students in Ocala for a special TV sequence with, gathered around cameras on the Plaza of the program's emcee, Jack Linkletter. - the A m e r I c a s yesterday as Hootenanny He spent a few minutes out on the lawn stars taped the show's first outdoor in the Plaza before handlers put him sequences. back in the truck for his journey back Tonight's show will feature Johnny Cash, 1om e. Jo Mapes, Bob Gibson, Leon Bibb, the Albert I was turned out to "pasture" I Johnson Family, the Coventry singers and at Ocala two years ago and was replaced ALERT TUSSLES comedian Adam Keefe. -

Walter Winchell Part 52 of 58

FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION A/92/A 4.7%/Q-k/1} /i/4_f<;?_~*__ _ _ J P;92RT# /01Q1?/FE PAGES.»9292I.=92lL.;92Bl,E THISPART j ?_ W /1; --£-. FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION A» FILES CONTAINED IN THIS PART FILE # " PAGES AVAIL-ABLE :2 '-"2/6/jérmeamz/! __ ,{_é_~_'>_ _ _ _g /F .5--4/ J I ____'_ ;e1,§-F? x V ' . - ' - 'v"A-¢T'1-__-__ ;'j;;¢ <==o~=--q-5-; ~ ' _ .~ " _*f¢a> 92_ . _' _ -; in ?...:.Ew ' ah." rt -- '- - - - -v~' ~._ - 7- .-~.- -~.-.-..'--- -.-.--"Bali.-,:1'_.._-a .92.:.;,..-.3:-=._:. 7;}-..-F-_~'-I ' - - V -' -..- _ - _ 5 L --A .7 :_:__,. _. - _ ~ __ -, ' - _.1--1; - -- -~ -._.r. ., _,__,.., 4.». .-I .--.___.. rb=o.zB~1I-11-"-5" ' . L , <2 Y-'""""i.-.i_ A 4;-,_..,:" En 'I'oIoog___ . _ __ . ., ' ,_,_ . Y . .;. :1. -_' i Ii. Belmo1lt_.. 92,., .._ I , ., _ __. _- V-v _ _ _ , _...,,n.,:'__ n -- '92 . ; u . - -' ' '92 - _ - ~ _ Q. - -- , _- . r . 92_-I.! . N.,., i, 1- _ -_..--- _ _ 1 ~ ., Ir. lfohr 4 _,- 1| ..- ; w-~%- =:--.-.=e." = 1 lb. cum, _ __ _ _V .:.__ _._..-V-7*:-T . ,:J ___ --~..- , - FBI,--.¢:~.,.-7q,;Z¢.3....»f_._... _._ Ir. _ Hr. a " " - Hr. ag _,, F J >'- V-:_r% _ ' --". -

This Resource Guide for Teachers Cf English to Resource. and the Second Dealing with the Language Itself. the First Mat Eria.Ls

D COMMIT REMIE SD 171 119 EL 010 2`72 AUTHOR -one, Eleanor Cam,, Cc 11E. ;Aridc) the rs TIT1B Resources for TESOL Teaching: A Handbookf English to Speakc,rs o fOtb. er Languages. & Tr aining Journal Pep mies, Nc.26. ilkTS7TTUTION Peace ,Corps, Wash ingt r),C, PUB PATF., se p 781. NO-T I 216p. A YAILABLE FROM Volunteers in r-ecnnical aystance, de Island Avenue, Mt.Baini.er,ZaairyLard 20822 EDES PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage.. ret SSIPTORs Communicative c ompete (Le r.gu-acie s) ;*Engli-sh (s econd Languag e) *Grammar L. angu age in structi- Languag e S kills; *La nguage Teacher s ;,Orthographic SymbolsP tonet is rsc xi_ rtion; pronunciation In struction ;e ading Resource .Guides; *5 ec Language Learni ng;' eachi.nc4 Technilves; Verbs ; Vocabulary Development; Uriting ASST B ACT This resource guide for teachers cf English to p _Xers of other languagescontains twc sections, one dealing-with resource. and the seconddealing with the language itself. The first section containsleaching ideas, tech rigue so: and suggestions onhow to, Predent-,' develop, and reinfo rcer era = iationgrammar, vccaloulary ,reading, writing, and conversatdcm. Anadditional_ chap$te on games astechniques for reviewing thP Lang uage skills already taught is .included. The second sectiondel ls with the follwing asFects 4Of Lang uage:(1)a comparison. of f cur phoneticalphabets;(2) -amples- of minimal pairs;(3)glossa Ty cE grammatical terms;(4) irregular verbs;(5)verb tenses;(6) .diff ement ways of expressing the future ;(7)troublesome ver bs ;,(8)mod.02. auxin arias; 'two-word verbs;(10) prefixes and suffixes;( 11)Latin and Greek, Nro_ots;(12)vocabulary categories; (13) comonly usedHerds; (14) question -type s;(15) punctuation rules;(16) spelling rules;(17) British. -

Contribution of the Scandinavian and Germanic People to the Development of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1926 Contribution of the Scandinavian and Germanic people to the development of Montana Oscar Melvin Grimsby The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Grimsby, Oscar Melvin, "Contribution of the Scandinavian and Germanic people to the development of Montana" (1926). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5349. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5349 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE SCANDINAVIAN AND GERMANIC PEOPLE TO THE DEVELOPMENT OP MONTANA *>y O. M. GrimsTjy 19S6 UMI Number: EP40813 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI* UMI EP40813 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

Togetter 12/01/19 23:48

★HIGH&MIGHTY COLOR★ - Togetter 12/01/19 23:48 フォローする @togetter_jp mutamac まとめ作成 お知らせ 24 設定 ログアウト 発表!!トゥギャッターまとめで2011年を振り返ろう!まとめランキングベスト20をこちらで公開中だよ。 トップページ 注目のまとめ 今週人気のまとめ 新着のまとめ いいね! 5,000 検索 すべて ニュース 社会 地域 芸能・スポーツ IT・Web 科学・教養 カルチャー 趣味 生活 仕事 ネタ・お笑い ログ・日記 震災 速報 国内 アジア アメリカ ヨーロッパ その他 2011/10/12 12:31:39 カルチャー 音楽 ハイカラ bleach 一輪の花 + ★HIGH&MIGHTY COLOR★ ハイカラの歌をYOU-TUBEでまとめてみました♪ 『一輪の花』と『Amazing』大好き(^-^) by hinagiku_may 0 fav 377 view いいね! Tweet 4 0 お気に入りに登録ならここをクリック! まとめ メニューを開く まとめを作成する プロフィール まだ自己紹介が設定されていませ ん。 hinagiku_may マイタグ: 正当防衛 フォローする このユーザの更新状況や活動をチェック! High and Mighty Color Ichirin no Hana 16:9 HQ フォローしている フォローされている 2 0 まとめ お気に入り コメント 18 21 4 自家発電の話がいつの間にか人を騙して儲け ようという悪巧みに変わる人達 『ツイートを偽造された件のまとめ』 @minako_genkiさんによるRTが怖いです。 @akindoh さんからの暴言 (数時間だけで コレ) 藍染botと私と仲間とミドリムシ♪ もっと見る High and Mighty Color Amazing 注目のまとめリスト v(*´∀`*)vタイバニえへ顔まとめ v(*´∀`*)v PKAnzug先生による「甲状腺癌は実 はその気になって探せばすご.. #文豪にtwitterやらせたら トゥ ギャられ確定文豪まとめ http://togetter.com/li/199628 1/11 ページ ★HIGH&MIGHTY COLOR★ - Togetter 12/01/19 23:48 3月11日福島県民集会・パレードとバ スツアーへの反応まとめ 早川由紀夫 (hayakawayukio)「あん なひどいことをした福島農家.. 「ステマ祭」と、「それは2ちゃんか らの抜粋です」「私が書い.. High & Mighty Color - Pride トゥギャッター通信 第61回「謎の雲とセンター試験」 第60回「江戸ハックとお雑煮」 号外「トゥギャッターが選んだ傑作まとめ20 選」 第59回「金持ち磯野と思い出大掃除」 第58回「Winny無罪とPS Vita」 ハイカラ [PV] HIGH and MIGHTY COLOR "good bye" トゥギャッターからのお知らせ とっても簡単!はじめてのトゥギャッター.. まとめへのフィードバック機能がつきまし た! まとめ作成画面でつぶやきへの返信の流れ.. トゥギャッターのまとめは「はてなダイア.. t.coやbit.lyなど、短縮された.. Rosier (Cover) - High and Mighty Color 過去のアーカイブ 2012-01-18の人気まとめ 2012-01-17の人気まとめ 2012-01-16の人気まとめ 2012-01-15の人気まとめ 2012-01-14の人気まとめ HIGH and MIGHTY COLOR - OVER (English Subtitles) http://togetter.com/li/199628 2/11 ページ ★HIGH&MIGHTY COLOR★ - Togetter 12/01/19 23:48 最近追加された商品 HIGH and MIGHTY COLOR - Remember MV with lyrics 情報社会の秩序と信頼―IT時代 の企業・法・政治 テレビ、新聞じゃわからないテ ロ・戦争がイッキにわかる本 (ア スキーQ&Aブックス) これが自衛隊の実力だ (News package chase (038)) Case-Mate iPhone 4 CREATURES: Bubbles Monkey Cas. -

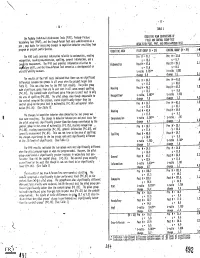

Cham. 1.7 IC Pre M 2 70 M7-1

- 11 - 10 - TABLE I COGRITIVE MUM COMPARISONS OE lhe Peabody Individual Achievement Tests(PIAT), Peabody Picture PILOT AND CONTROL GROUP TEST Vocabulary Test (PAM, and the DrawiA-PersonTest were adodnistered on a RESULTS ON PIATPPVI 'AND DRAW-A-PERS011 TEST changes in cognitive behavior resulting from pre : post basis tor assessing prugram or project participation. CONTROL GROUP (ft 2 29) .,t-11 COGNITIVE ARCA PILOT GROUP (11 . 31) The PIAT tests provided intonation relatilie to matheowtics,reading Pre M . 37.8 1.1 ! PreM : 41.7 reco nition, reading comorehension,spelling, general information, and a s . 15.3 The HI test provides information relative to , Post h 2 39.3 3.1 ChiPh site measurement, Mathematics Post M 3 47.6 developmental or s : 8,5 vng;lula.ry skill, and the Draw-A-Person Test served as a s 2 11.6 1,083 artistic'ability measure. t-ratio3.721" t-ratio 2,1 change l5.9 . change 1.5 The results.of the PIAT tests indicated that there wasno significant .5 Pre M . 39.3 Pre M . 41.0 differences between the groups ih all areas when theproject began (see s . 11.2 s . 10,0 The pilot group Table 1), This was also true fur the PPVT test results. Post M . 42.2 1,2 Readng Post M . 46,3 wade signi f icamt gains from preio post test in all areas except spelling s . 9.6 . only s . 15.3 (P< .01), The control c@de significant gaihs from pre to post test in 1.933 t-ratIci., 5,887" 1-ratite though comparable to Recognition the area of spelling (P4:.05).' The pilot group, even 4,3 change 7.0 change 1.2 the control group on the pretest, scoredsignificantly higher than the PreM . -

Congressional Record-Senate. 8011

1894. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 8011 PETITIONS, ETC. NEBRASKA STATE CLAIM. Under clause 1 of Rule XXII, the following petitions and papers The VICE-PRESIDENT- laid before the Senate the amend were laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: ments of the House of Representatives to the bill (S. 463) to, re By Mr. BELTZHOOVER: Petition of citizens of Hanover, imburse the State of Nebraska the expenses incurred by that Pa., in favor of amending the Gorman bill so as to exclude fra State in repelling a threatened invasion and raid by the Sioux ternal beneficial associations from the provisions of the income in 1891. tax-to the Committee on Ways and Means. The amendments of the House of Representative were on By Mr. FITHIAN: Evidence to accompany bill granting· in page 1, line fi, to strike out" pay" and insert in lieu thereof crease of pension to Lemuel J. Essex_-to the CoiJ?.mittee on In the words '' report to Congress." valid Pensions. On pages, 1 and 2, lines 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18, to strike out" and By Mr. HENDERSON of Iowa: Petition from the Letter Car that the sum of $42,000 be, and the same is hereby, appropriated riers' Association of New York, asking favorable action on bill out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, increasing salaries of letter-carriers-to the Com.mitte.e on the or so much thereof as may be necessary, to carry out the pro Post-Office and Bost-Roads. visions of this act." By Mr. -

How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk

Praise for How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk “THE PARENTING BIBLE.” —THE BOSTON GLOBE “WILL BRING ABOUT MORE COOPERATION FROM CHILDREN THAN ALL THE YELLING AND PLEADING IN THE WORLD.” —THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR “AN EXCELLENT BOOK THAT’S APPLICABLE TO ANY RELATIONSHIP.” —THE WASHINGTON POST “PRACTICAL, SENSIBLE, LUCID . THE APPROACHES FABER AND MAZLISH LAY OUT ARE SO LOGICAL YOU WONDER WHY YOU READ THEM WITH SUCH A BURST OF DISCOVERY.” —THE FAMILY JOURNAL “AN EXCEPTIONAL WORK, NOT SIMPLY JUST ANOTHER ‘HOW-TO’ BOOK . ALL PARENTS CAN USE THESE METHODS TO IMPROVE THE EVERYDAY QUALITY OF THEIR RELATIONSHIPS WITH THEIR CHILDREN.” —FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM 30th–Anniversary Edition Updated with new insights from the next generation YOU CAN STOP FIGHTING WITH YOUR CHILDREN! Here is the bestselling book that will give you the know-how you need to be more effective with your children—and more supportive of yourself. Enthusiastically praised by parents and professionals around the world, the down-to-earth, respectful approach of Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish makes relationships with children of all ages less stressful and more rewarding. Now, in this thirtieth-anniversary edition, these award- winning experts share their latest insights and suggestions based on feedback they’ve received over the years. Their methods of communication—illustrated with delightful cartoons showing the skills in action—offer innovative ways to solve common problems. You’ll learn how to: • Cope with your child’s negative feelings —frustration, disappointment, anger, etc. • Express your anger without being hurtful • Engage your child’s willing cooperation • Set firm limits and still maintain goodwill • Use alternatives to punishment • Resolve family conflicts peacefully Internationally acclaimed experts on communication between adults and children, ADELE FABER and ELAINE MAZLISH have won the gratitude of parents and the enthusiastic endorsement of the professional community. -

New Motor Bicycles That Goover Forty Miles an Hour

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 1898. 25 BIGGEST KANGAROO DRIVE OF THE YEAR -In Australia- In the colonies and besides fulfillingthe right and left wings usually contrive, object of Its originators in decimating to keep the frightened game within the immense mobs of the squatter's bounds and thus they rush on to the arch enemy it supplies a splendid day's ambuscade in front of them. sport to all lovers of the gun. The After Ihad taken up my position I method is fashioned on very similar had not long to wait in order to gratify lines to the great "rabbit drives" held my sporting Instincts. In the San Joaquin Valley. The kan- First came a hare toward me, rush- garoo drives though are far more ex- ing like the wind. But Ilet him go by citing and sportsmanlike. and also a number of others. The These drives are of frequent occur- movement of these animals was a clear rence, and In some parts of the colonies indication that the big game had begun of New South Wales and Queensland to move and Istood ready with both It is quite possible to be present at an barrels of my gun "cocked." organized drive at least once a week. Almost before Icould realize itIsaw Of course these drives seldom yield any a big kangaroo jumping toward me. large numbor of kangaroos. For thope He came like a cyclone, easily covering one must go to the outlying districts, from 15 to 20 feet at every leap. where drives are not frequent. -

ED234413.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 234'43.3 CS 207 855 \ 4 AUTHOR HarSte, Jerome C.;. And Others TITLE The Young Child as Writer-Reader,and Informant. Final Report. INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., Bloomington.Dept: of Language Education. SPONS AGENCY National 'nat. of Education (ED),Washington, DC. PUB'DATE Feb 83 GRANT NIE-d-80-0121 NOTE 479p.; For related document,see ED 213 041. Several pages may be marginally legible. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Development; *ChildLanguage; Educational Theories; Integrated Activities;Language Research; *Learning Theories; *LinguisticTheory; Preschool Education; Primary Education;Reading Instruction; Reading Skills; *SociolinguisticS;SpellingrWriting Instruction; *Writing Research;Writing Skills; *Written Language IDENTIFIERS *Reading Writing' Relationship ABSTRACT The Second of a two- volumereport, this document focuses on the study of writtenlanguage growth and development 3-, 4-, 5 -, and 6-year-old children. among' The first section of thereport introduces the program of researchby examining its methodological and conceptual contexts. TheSecond section provides illustrativeand alternative looks at theyoung child as writer-reader and reader=writer,, highlighting key_transactions in literacy and literacy learning:. The third section pullstogether and kdentifies how the researchers' thinking about_literacyandliteracy learning changedas a result of their research and offersan evolving model of key proceises involved in literacylearning. The fourth section comprises a series of papers dealing with the spellingprocess, children's writing; developmentas seen in letters, rereading, and therole of literature.in the language poolof children. The fifth section contains taxonomies developed forstudying the surface textscreated by children: in the study. Extenslivereferences are included,.andan addend6m includes examples of tasksequence and researcher script, "sample characteristics" charts,and Sample characteristics statements. -

Music Practices Across Borders

Glaucia Peres da Silva, Konstantin Hondros (eds.) Music Practices Across Borders Music and Sound Culture | Volume 35 Glaucia Peres da Silva (Dr.) works as assistant professor at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Her research focuses on global markets and music. Konstantin Hondros works as a research associate at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen. His research focuses on evaluation, mu- sic, and copyright. Glaucia Peres da Silva, Konstantin Hondros (eds.) Music Practices Across Borders (E)Valuating Space, Diversity and Exchange The electronic version of this book is freely available due to funding by OGeSo- Mo, a BMBF-project to support and analyse open access book publications in the humanities and social sciences (BMBF: Federal Ministry of Education and Research). The project is led by the University Library of Duisburg-Essen. For more information see https://www.uni-due.de/ogesomo. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (BY) license, which means that the text may be remixed, transformed and built upon and be copied and redistributed in any medium or format even commercially, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

Pearl Harbor Attack

\< "^ Given By U. S. SUPT. OF DOCUMENTS t 3^ PEARL HARBOR ATTACK HEARINGS BBFORB THB JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE INVESTIGATION OF THE PEAEL HARBOE ATTACK CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES ->, ^,,, ., ^ "^ SEVENTY-NINTH CONGRESS -^^f' ^-^ FIRST SESSION < ^ PURSUANT TO « ,^ i • S. Con. Res. 27 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING AN INVESTIGATION OF THB ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR ON DECEMBER 7, 1941, AND EVENTS AND CIRCUMSTANCES RELATING THERETO PART 34 PROCEEDINGS OF CLARKE INVESTIGATION Printed for the use of the Joint Committee on the Inyestigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack PEARL HARBOR ATTACK HEARINGS BEFORE THE i/tC'^ -^^ • " JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE INVESTIGATION OF THE PEAKL HARBOR ATTACK CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES SEVENTY-NINTH CONGRESS 12^7^7 FIRST SESSION • xZ PURSUANT TO • /j^ S. Con. Res. 27 p-a. ^<l A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING AN ' ' INVESTIGATION OF THE ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR ON DECEMBER 7, 1941, AND EVENTS AND CIRCUMSTANCES RELATING THERETO PART 34 PROCEEDINGS OF CLARKE INVESTIGATION Printed for the use of the Joint Committee on the Investigation of tlie Pearl Harbor Attack UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 79716 WASHINGTON : 104G OF DOCUMENTS . U. S. SUPtR»NTENDENT SEP 231946 JOINl COMMITTEE ON THE INVESTIGATION OF THE PEARL HARBOR ATTACK ALBEN W. BARKLEY, Senator from Kentucky, Chairman JERE COOPER, Representative from Tennessee, Vice Chairman WALTER F. GEORGE, Senator from Georgia JOHN W. MURPHY, Representative from SCOTT W. LUCAS, Senator from Illinois Pennsylvania OWEN BREWSTER, Senator from Maine BERTRAND W. GEARHART, Representa- HOMER FERGUSON, Senator from Michi- tive from California gan FRANK B. KEEFE, Representative from J. BAYARD CLARK, Representative from Wisconsin North Carolina COUNSEL (Through January 14, 1946) William D.