Tuaua V. United States of America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day Hikes EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Trails Map

TUTUILA ISLAND Please Note: The colored circles with numbers refer to the trail location on the backside map. Easy Moderate Challenging 1 Pola Island Trail 2 Lower Sauma Ridge Trail 4 Le’ala Shoreline Trail Blunts and Breakers Point Trails 8 World War II Heritage Trail 10 Mount ‘Alava Adventure Trail This interpretive trail takes you to an archeological site Hike past multiple World War II installations that helped This challenging loop trail takes you along ridgelines This short, fairly flat trail leads to a rough and rocky This trail is located outside of the national park, on These trails are located outside of the national park. beach with views of the coastline and Pola Island. of an ancient star mound. Along the trail are exhibits private land, and provides access to the Le’ala Shoreline protect American Samoa from a Japanese invasion. with views of the north and central parts of the National Natural Landmark. Located at the top of these points are gun batteries and spectacular views of the northeast coastline of Also, enjoy the tropical rainforest and listen to native national park and island. Hike up and down “ladders” Distance: 0.1 mi / 0.2 km roundtrip that protected Pago Pago Harbor after the bombing the island and the Vai’ava Strait National Natural Beginning in the village of Vailoatai, this trail follows bird songs. Along the last section of the trail, experience or steps with ropes for balance. There are a total of of Pearl Harbor in 1941. They symbolize American Due to unfriendly dogs, please drive past the last house Landmark. -

Bvarc Beacon

BVARC BEACON Newsletter of the Brazos Valley Amateur Radio Club AMATEUR RADIO FOR SOUTHWEST HOUSTON AND FORT BEND COUNTY JUNE 202020 202020 VOLUME 444444 ISSUE 666 BVARC JUNE GENERAL MEMBERSHIP MEETING Thursday, June 11, 2020 7:30pm, an online meeting venue will be announced on the website and email reflector. We’ll have a presentation by Scott Tilley (VE7TIL) on the lost Zombie satellite he re-discovered and has been able to track and listen to. We won't be having IN PERSON meetings for at least another month or two. Club Business meetings will be held over a conference call, and Club meetings will not be held in person (Facilities are closed) but we are arranging a streaming meeting. May (and June) VE - FCC TESTING SESSION (NO) RESULT We’re looking for a testing location, for maybe later in June, to do several make-up sessions. There is a backlog of interest in resuming testing. When we do re-start, we’ll be implementing some social distancing – partly dependent on the facility requirements and also to manage the seemingly large backlog of testing candidates. Remote testing is an interesting option, but on investigating it, only one candidate can be proctored at a time, which stretches VE resources and time. Stay tuned. When times are normal, examination sessions are held each month, usually on the same day as the Saturday BVARC Board meeting. These sessions are at the Bayland Park Community Center, 6400 Bissonnet St., Houston TX 77074 Details for candidates are found at www.bvarc.org/home/amateur-license/ Call Mark Janzer, K5MGJ at (832) 875-0526 or eMail: ( [email protected] ) to pre-register. -

Island Blood the Stories of Samoan Vietnam War Veterans

ISLAND BROTHERS/ ISLAND BLOOD THE STORIES OF SAMOAN VIETNAM WAR VETERANS A portfolio project submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES April 2012 By Peter L. Akuna Sr. Committee Members Tarcisius T. Kabutaulaka (Chairperson) Julie Walsh Lola Quan Bautista This Project is dedicated to: Cpl. Lane Fatutoa Levi of Fagatogo, American Samoa SP4 Fiatele Taulago Teo of Pago Pago, American Samoa LCPL. Fagatoele, Lokeni of Mapusaga, American Samoa PFC. Benjamin Galu Willis of Leone, American Samoa Whose names are engraved on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall at Arlington, Virginia And to my Pacific Islands brothers and sisters of American Samoa who had served in the Vietnam War 2 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to the Vietnam Veterans of Samoa who shared their stories with me. It took a lot of courage for them to open their heart and souls and reveal their personal stories and relive horrifying memories of a war that they would rather leave behind in the abyss of their memories. By telling their stories, they have assisted in my endeavor to make known to the world the sacrifices of Pacific Islanders in the United States military. Here, the stories are about Pacific Islanders, more specifically Samoans in the Vietnam War. I thank each and every one of them. Their heartfelt cooperation exceeded my expectations. I also am grateful to Dr. Terence Wesley-Smith, the Director of the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and chair of the Center’s graduate program and members of the graduate committee for accepting me into their program. -

Another Sexual Harassment Complaint Filed At

PAGO PAGO, AMERICAN SAMOA THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 2018 $1.00 US Army Capt. Kurk Cruz Diaz, who is the Guam Recruit- ment Company Commander (le ) shakes hands with Bluesky Communications Country Man- ager, Raj Deo a er signing the Army Partnership for Youth Suc- cess (PaYS) program, yesterday morning. e US Army and Bluesky C M Communications memorandum Y K of agreement for the PaYS pro- gram is the rst in the Asia and Paci c region. (See story and more photos inside today’s issue) [photo: FS] ONLINE @ SAMOANEWS.COM DAILY CIRCULATION 7,000 Another sexual harassment complaint fi led at DPS THE SECOND ONE REPORTED IN LESS THAN A MONTH by Ausage Fausia two weeks ago, to report the she pendent investigator, instead of According to the statement, to the Fagaitua Substation, and Samoa News Reporter had been sexually harassed by a having DPS handle them. three police offi cers were inside were engaged in small talk. It Another sexual harassment ranking DPS offi cial. Samoa News points out that the police unit on the day in was in the middle of their joking complaint at the Department of This is the second case of efforts to obtain a comment question: the female cop, her session that, according to the Public Safety has surfaced. This sexual harassment that has been from DPS Commissioner Le’i male superior, and another male victim, her supervisor told the time, it involves a young female reported out of DPS in less than Sonny Thompson regarding the offi cer. male cop that he shouldn’t bring cop, who has been in the force a a month. -

World War II Instajlations on Tutuila Island

Tiineline American Samoa, like many other South Sea islands, is a tropical Today, all that is left of this history are some historic buildings, April 2, 1942: The first airplanes of Marine Air Group 13 (i-.•lAG- paradise in the South Pacific. But beneath the dramatic mountain gun sites, stories and photos of an era when the Ur.iited States 13) landed at Tafuna Air Base. Few of the Marine pilots were peaks and swaying palm trees, lies a strong U.S. Naval and took control of th e eastern Samoan Islands. It was at a time experienced and training conditions were difficult. Heat, bugs, mud World War II connection that lasted a good part of the late when the European powers were dividing up the Pacific and then and rain made even the construction of an adequate camp difficult. 1800s and over half the 1900s-spanning nearly 90 years. sought to stop Japan as it began its invasion of the Pacific. iNhile attempting to train aviators, the men of MAG-13 also put in time as infantry, each squadron functioning as one company of two platoons plus one .30 caliber machine gun platoon. The group was supported in these defensive efforts by a tank company, a heavy February 14, 1872: Commander Richard W. Meade, US1 , February 17, 1941: Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Harold weapons platoon, a three-inch battery, and one section of the commanding USS Narragansett, anchored in Pago Pago Harbor to Ravnsford Stark, instructed the Commandant of U.S. Naval Station islands barrage balloon squadron. investigate the possibility of establishing a naval station there. -

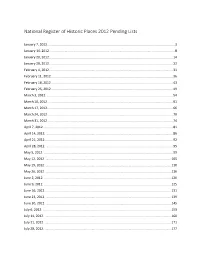

National Register of Historic Places Pending Lists for 2012

National Register of Historic Places 2012 Pending Lists January 7, 2012. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 14, 2012. .......................................................................................................................................... 8 January 20, 2012. ........................................................................................................................................ 14 January 28, 2012. ........................................................................................................................................ 22 February 4, 2012. ........................................................................................................................................ 31 February 11, 2012. ...................................................................................................................................... 36 February 18, 2012. ...................................................................................................................................... 43 February 25, 2012. ...................................................................................................................................... 49 March 3, 2012. ............................................................................................................................................ 54 March 10, 2012. ......................................................................................................................................... -

Damaged and Threatened National Historic Landmarks 1995

Damaged and Threatened National Historic Landmarks 1995 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Cultural Resources Heritage Preservation Services This is an overview of the condition of National Historic Landmarks in the United States in 1995. To see the complete text concerning Landmarks judged to be at risk, including descriptions and recommendations for mitigation of threat or damage, please visit the National Park Service Cultural Resources web site at: http://www.cr.nps.gov. This site has extensive information on preservation and documentation programs administered by the National Park Service as well as information on financial assistance and tax credits for historic preservation. This year's report on damaged and threatened National Historic Landmarks may be downloaded from the National Park Service Cultural Programs FTP site at: ftp.cr.nps.gov/pub/hps/nhlrisk.w51. Damaged and Threatened National Historic Landmarks 1995 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Washington, D.C. CERTIFICATES OF APPRECIATION FOR ASSISTANCE TO NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS The National Park Service wishes to acknowledge the outstanding contributions of the following individuals and organizations to the preservation of National Historic Landmarks: Alabama Historical Commission, for stabilization and repointing of Fort Morgan and preservation of its Endicott concrete and wooden structures: Baldwin County, Alabama The University of Tampa, for repairs to the roof and foundation of the Tampa Bay Hotel and for restoration of its -

American Samoa Renewal |

Guide for the Cruise Line Industry in AMERICAN SAMOA Robert Burk 2005 Pacific Island Fellows Program US Department of the Interior Office of Insular Affairs Disclaimer: This document has been prepared by a masters student in Travel Industry Management to disseminate information on American Samoa’s cruise industry for the purposes of the 2005 Business Opportunities Mission sponsored by the U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs. The views and recommendations contained in this document, however, are solely those of its author and not the U.S. Government or any agency or officer thereof. Those intending to initiate ventures in this location are advised to conduct independent due diligence. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 2 GEOGRAPHY.............................................................................................................................................. 2 TUTUILA ISLAND ........................................................................................................................................ 2 MANU'A ISLANDS ....................................................................................................................................... 3 AUNU’U ISLAND ........................................................................................................................................ -

Visitor Guide

National Park Service National Park of American Samoa U.S. Department of the Interior Paka Fa’asao o Amerika Samoa Visitor Guide Lōmiga 1 | Volume 1 A taupou, or the daughter Suesue Atumotu Explore the Islands of a village chief, performs Sā o le Lalolagi of Sacred Earth a cultural dance. alofa! E fa’afeiloa’i atu le Paka Fa’asao o ello! The National Park of American Amerika Samoa ia te oe. O se si’osi’omaga Samoa welcomes you into the heart of the To mata’aga, leo ese’ese, ma ituaiga aga HSouth Pacific, to a world of sights, sounds, ma faiga e te lē maua i isi paka fa’asao a le Iunaite and experiences that you will find in no other Setete. E tu tonu i le 2,600 maila i le itu i saute i national park in the United States. Located some sisifo o Hawai‘i, ma o lenei paka fa’asao e mamao 2,600 miles southwest of Hawai‘i, this is one of the ese ma nofoaga ‘ainā i le Iunaite Setete. most remote national park’s in the United States. E te lē maua fale ua masani ai e pei You will not find the usual facilities ona maua i isi paka fa’asao. Peita’i, a of most national parks. Instead, fa’apea o oe o se tagata su’esu’e, e te with a bit of the explorer’s spirit, maua nu’u tuufua, o la’au ma meaola you will discover secluded villages, e seāseā vaai i ai, matafaga oneonea, rare plants and animals, coral sand atoa ai mata’aga i le fogaeleele ma le beaches, and vistas of land and sea. -

National Historic Landmarks Program

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM LIST OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE July 2015 GEORGE WASHINGTOM MASONIC NATIONAL MEMORIAL, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA (NHL, JULY 21, 2015) U. S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE LISTING OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE ALABAMA (38) ALABAMA (USS) (Battleship) ......................................................................................................................... 01/14/86 MOBILE, MOBILE COUNTY, ALABAMA APALACHICOLA FORT SITE ........................................................................................................................ 07/19/64 RUSSELL COUNTY, ALABAMA BARTON HALL ............................................................................................................................................... 11/07/73 COLBERT COUNTY, ALABAMA BETHEL BAPTIST CHURCH, PARSONAGE, AND GUARD HOUSE .......................................................... 04/05/05 BIRMINGHAM, JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA BOTTLE CREEK SITE UPDATED DOCUMENTATION 04/05/05 ...................................................................... 04/19/94 BALDWIN COUNTY, ALABAMA BROWN CHAPEL A.M.E. CHURCH .............................................................................................................. 12/09/97 SELMA, DALLAS COUNTY, ALABAMA CITY HALL ...................................................................................................................................................... 11/07/73 MOBILE, MOBILE COUNTY, -

National Register of Historic Places Received Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use omy National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________________________ 1. Name__________________________ historic American Samoa's Defenses: Blunts Point Battery and or common Blunts Point Battery 2. Location street & number Matautu Ridge not for publication city, town vicinity of Pago Pago state American Samoa code 60 county Tutuila Island code 050 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private x unoccupied commercial park __ structure __ both work in progress __ educational private residence _.x_ site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted x government scientific __ being considered _X- yes: unrestricted __ industrial transportation __ no military x other: private property 4. Owner of Property name Government of American Samoa street & number city, town Pago Pago __ vicinity of state American Samoa 96920 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Government of American Samoa street & number city, town Pago Pago state American Samoa 96920 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Blunts Point Naval Gun has this property been determined eligible? __x . yes __ no date . x_ federal state . county local depository for survey records National Register of Historic Places City, town Washington state D.C. 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _ excellent J< deteriorated unaltered x original site __ good _ ruins x altered moved date __ fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The World War II Blunts Point battery is located on Matautu Ridge at Tulutulu (Blunts) Point on the west side of Pago Pago Harbor and southeast of the village of Utulei. -

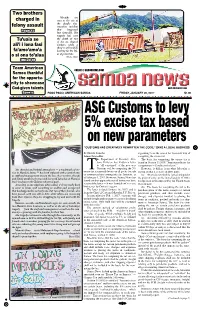

ASG Customs to Levy 5% Excise Tax Based on New Parameters “Customs Has Creatively Rewritten the Code,” Says a Local Business

Two brothers Wreaths are charged in seen at the site of the deadly elec- felony assault trocution incident Page 15 that happened last Saturday. The tragedy has seen Tu’uaia se the death of two of the six injured ali’i i lona fasi workers, while a third is still in ICU fa’amo’amo’a battling for his life, as of press time. o si ona to’alua [Photo: THA] Itulau 18 Team American ONLINE @ SAMOANEWS.COM Samoa thankful for the opportu- C M nity to showcase Y K God-given talents DAILY CIRCULATION 7,000 Sports PAGO PAGO, AMERICAN SAMOA FRIDAY, JANUARY 20, 2017 $1.00 ASG Customs to levy 5% excise tax based on new parameters “CuSTOMS HAS CREATIVELY REWRITTEN THE CODE,” SAYS A LOCAL BUSINESS By Rhonda Annesley is pointing to as the reason for their new way of Samoa News editor computing the excise tax. he Department of Treasury, Cus- The basis for computing the excise tax is toms Division has written a letter found in Section 11.1001 “Imposition-Basis for to “all concerned” of the new way computation —Conditional release.” Customs will be computing the 5% However, it differs from what Moetului is The cheerful and helpful atmosphere — a trademark of ser- exciseT tax it currently levies on all goods for sale saying, in that it is states in three parts: vice in Manu’a’s Stores — has been replaced with a somber one, or commercial use coming into the Territory, as (a) An excise tax shall be levied and paid at as staff and management mourn the loss of co-workers, friends of February 1, 2017.