Guide to Palestine – Israel Economic and Trade Relations Prepared By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 459.71 Kb

מרכז המידע הישראלי לזכויות האדם בשטחים (ע.ר.) One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Rim ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment expressed the frustration of Gaza residents that results from Israel’s rigid policy of closure on the Gaza Strip following the signing of the Oslo Agreements. The gap between the metaphor of the Gaza Strip as a prison and the reality in which Gazans live has rapidly shrunk since the outbreak of the intifada in September 2000 and the imposition of even harsher restrictions on movement. The shrinking of this gap is the subject of this report. Israel’s current policy on access into and out of the Gaza Strip developed gradually during the 1990s. The main component is the “general closure” that was imposed in 1993 on the Occupied Territories and has remained in effect ever since. Every Palestinian wanting to enter Israel, including those wanting to travel between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, needs an individual permit. In 1995, about the time of the Israeli military’s redeployment in the Gaza Strip pursuant to the Oslo Agreements, Israel built a perimeter fence, encircling the Gaza Strip and separating it from Israel. -

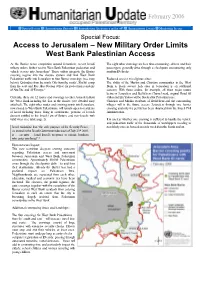

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

B'tselem and Hamoked Report: One Big Prison

One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Reem ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Cover photo: Palestinians wait for relatives at Rafah Crossing (Muhammad Sallem, Reuters) ISSN 0793-520X B’TSELEM - The Israeli Center for Human Rights HaMoked: Center for the Defence of in the Occupied Territories was founded in 1989 by a the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte group of lawyers, authors, academics, journalists, and Salzberger is an Israeli human rights Knesset members. B’Tselem documents human rights organization founded in 1988 against the abuses in the Occupied Territories and brings them to backdrop of the first intifada. HaMoked is the attention of policymakers and the general public. Its designed to guard the rights of Palestinians, data are based on independent fieldwork and research, residents of the Occupied Territories, official sources, the media, and data from Palestinian whose liberties are violated as a result of and Israeli human rights organizations. Israel's policies. Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning Since the beginning of the occupation, line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten Palestinians traveling from the Gaza Strip to years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Egypt through the Rafah crossing have needed Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment a permit from Israel. -

Great Return March": Demonstrations of April 27, 2018, and Continuation

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ה ש ל מ רמה כ ז מל ( ( ו למ תשר מ" מה ו ד י ע י ן ה ש ל מ ( ( למ מ" ¶ The “Great Return March": Demonstrations of April 27, 2018, and continuation to be expected April 29, 2018 Palestinians cutting the security fence near the Karni crossing (IDF Spokesperson’s Office, April 27, 2018) Incidents on Friday, April 27 Overview On Friday, April 27, 2018, the fifth Friday of the demonstrations of the "Great Return March," riots took place along the Gaza border with Israel. An estimated 10,000 Palestinians participated in the incidents in five focal points. The events of last Friday included many acts of violence, the most serious of which was an attempt to break through the fence and penetrate into Israel in the Karni crossing area. In view of the blatant attempt to violate Israel’s sovereignty, the IDF spokesperson announced a new policy of response, in which every violent activity would be met with violent activity against Hamas. As part of this policy, Israel Air Force aircraft attacked six targets of Hamas’s naval force. The acts of violence on the last Friday came into expression in several ways: throwing stones and rocks; throwing IEDs and hand grenades at IDF soldiers; flying kites over Israeli territory with burning objects attached to them (some of the kites caused fires in Israel and extensive damage); sabotaging the security fence along the border and the barbed wire close to it (including two incidents of setting fire to the fence, pulling the fence and attempts to cut it). -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I T E D N A T I O N S N A T I O N S U N I E S OCHA Weekly Report: 4 – 10 July 2007 | 1 OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 4 – 10 July 2007 Of note this week Gaza Strip: • The IDF killed 11 Palestinians, injured 15, and arrested 70 during its incursion into the area southeast of Al Bureij Camp (Central Gaza). In addition, three Palestinians were injured, including a 15-year-old boy, during IDF military operations southeast of Beit Hanoun. • A total of 23 Qassam rockets and 33 mortar shells were fired from Gaza towards Israel, of which at least four rockets and 29 mortar shells targeted Kerem Shalom crossing. Five rockets landed in the Palestinian area. Hamas and Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility. No injuries were reported. • The Palestinian Ministry of Health confirmed that it has returned at least 25 corpses to Gaza via Kerem Shalom since the closure of Rafah until 5 July. In all cases, the persons had passed away in Egyptian or other overseas hospitals and not at the border. • Senior Palestinian traders were able to cross Erez crossing this week for the first time since 12 June. Humanitarian assistance continues to enter Gaza through Kerem Shalom and Sufa. Critical medical cases with special coordination arrangements exited through Erez. Karni was open on two days for the crossing of wheat and wheat grain. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 3 October 2001 English Original: English/French

United Nations A/56/428 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 October 2001 English Original: English/French Fifty-sixth session Agenda item 88 Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories Note by the Secretary-General* The General Assembly, at its fifty-fifth session, adopted resolution 55/130 on the work of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories, in which, among other matters, it requested the Special Committee: (a) Pending complete termination of the Israeli occupation, to continue to investigate Israeli policies and practices in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and other Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967, especially Israeli lack of compliance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, and to consult, as appropriate, with the International Committee of the Red Cross according to its regulations in order to ensure that the welfare and human rights of the peoples of the occupied territories are safeguarded and to report to the Secretary- General as soon as possible and whenever the need arises thereafter; (b) To submit regularly to the Secretary-General periodic reports on the current situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem; (c) To continue to investigate the treatment of prisoners in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and other Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967. -

Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee

Economic Monitoring Report Public Disclosure Authorized to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee March 19, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized www.worldbank.org/ps 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter I: Recent Developments .................................................................................................................. 9 A. Economic Growth ................................................................................................................................ 9 B. Public Finance .................................................................................................................................... 11 The PA’s Fiscal Performance in 2017 ................................................................................................ 11 The 2018 Budget ................................................................................................................................. 12 C. Money and Banking ........................................................................................................................... 14 Chapter II: Gaza’s Evolution Over the Last Two Decades ......................................................................... 18 The Gaza Economy: From One Crisis to The Next ................................................................................ 18 The Humanitarian -

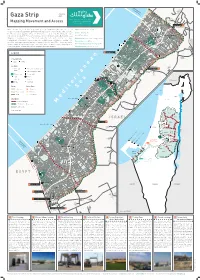

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

The Gaza Strip: Access Report May 2005

The Gaza Strip: Access Report May 2005 This report monitors monthly humanitarian access and movement in the Gaza Strip.1 All movement through the Gaza Strip’s borders is controlled by Israeli authorities. A security fence surrounds all of the Gaza Strip and sea access is restricted. Palestinian movement in and out of the Gaza Strip is through: • Erez crossing for workers and merchants who have permits to enter Israel; • Erez crossing for international humanitarian organisations; • Rafah crossing, between the Gaza Strip and Egypt, for access to other countries, including for overseas medical referrals; • Four commercial crossings of which Karni is the largest. Palestinian movement within the Gaza Strip is restricted: • through Abu Houli checkpoint in the central Gaza Strip; • by over 200 observed closure obstacles; • for Palestinians living in enclaves in close proximity to Israeli settlements.2 1. Gaza Strip Crossing Points A. Erez crossing and industrial estate Between January and March, there was a steady increase in the number of Palestinian workers and merchants entering Israel and the Erez industrial zone. This trend ended following the closure at Erez with the onset of the Jewish Passover holidays in the third week of April. The closure continued until 15 May for Palestinian workers and merchants, and 16 May for access to Erez industrial zone. This closure was imposed on the grounds that some workers had been submitting false documents while trying to leave the Gaza Strip. Restrictions continue on international humanitarian organisations who need prior coordination with Israeli authorities to enter and leave the Strip. A few high-level Palestinian UN staff are permitted to cross. -

GAZA Situation Map - As of 5Th of January 2009

GAZA Situation Map - as of 5th of January 2009 Reported Palestinian casualties as of 5 January 2009 * Killed 534 20% of killed Palestinians Siafa are civilians Injured Erez crossing point is partially open 2,470 Al Qaraya al Badawiya for a limited number of medical al Maslakh evacuations and foreign nationals. Madinat al 'Aw da Beit Lahiya * Beit Hanoun Situation Jabalia Camp Ash Shati' Camp • More than a million Gazans still have 'Izbat Beit Hanoun no electricity or water, and thousands Gaza Jabalia = 25 people = 25 people of people have fled their homes for safe Wharf shelter. Based on MoH as of 5 January 2009 40% of injured Palestinians are civilians * 'A rab Maslakh Beit Lahiya • Hospitals are unable to provide adequate Reported Israeli casualties as of 5 January 2009 Gaza intensive care to the high number of Killed * casualties. 8 of which 4 are civilians crossing point for fuels - open today. dead and at least injured Injured Nahal Oz • 534 2470 of which 46 are civilians 215,000 litres of industrial fuel along with 47 tonnes since 27 December, Source: Palestinian 106 of cooking gas have been pumped from Israel to Gaza Ministry of Health MoH, as of 5th of = 25 people January 2009. = 25 people Al Zahra Al Mughraqa Karni crossing * Based on the Israeli Magen David Adom and the Israeli (Abu Middein) Defence Force (IDF), as of 5 January point for goods • 60 IDF soldiers have been wounded in Gaza since Saturday the 4th of Jan., Priority Needs: including four who remain in serious condition. • Industrial fuel is needed to power the Gaza Power Plant. -

Breaking the Impasse: Ending the Humanitarian Stranglehold on Palestine

Breaking the impasse: ending the humanitarian stranglehold on Palestine November 2007 The upcoming Israeli–Palestinian meeting in Annapolis, Maryland provides an opportunity to address the humanitarian crisis, which is an essential step for successful negotiations leading to the end of the occupation of Palestine, and for delivering a just settlement and lasting peace for Palestinians and Israelis alike. Since January 2006, the people in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) have faced increasing suffering due to an array of policies adopted by the government of Israel and Western donors in the aftermath of Hamas’ victory in the parliamentary elections. For its part, Hamas has failed to stop armed Palestinian groups from undertaking indiscriminate rocket attacks on Israel. These attacks are unacceptable and must end. The Israeli government's blockade of the Gaza Strip constitutes collective punishment and cannot be justified. As a result of policies that include the severance of international aid to the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Israel's suspension of the transfer of tax revenues, the number of people in the occupied Palestinian territory experiencing deep poverty nearly doubled in 2006, to more than one million.1 In the first half of 2007, 58 per cent of Palestinians were living below the poverty line, and 30 per cent in extreme poverty.2 Essential- service delivery and Palestinian institutions were seriously undermined, and the economy declined alarmingly,3 contributing to unprecedented factional violence among Palestinians. The promise of the Annapolis meeting can only be achieved if negotiations end the siege of Gaza, lift debilitating restrictions on the movement of people and goods, and end settlement expansion in the West Bank, while ensuring all parties uphold international humanitarian and human-rights law and protect civilians. -

7 Environmental Assessment of the Gaza Strip Map 1. Regional

Map 1. Regional map 34°E 35°E 36°E UKRAINE ° LEBANONLEBANON Al Qunaytirah Black Sea BULGARIA ITALY 33°N TURKEY GREECE SYRIASYRIA Mediterranean Sea SYRIA Haifa Lake Tiberias Nazareth Dar'a EGYPT SAUDI LIBYA ARABIA Irbid a e Al Mafraq S n a e Az Zarqa' n a WESTWEST BANKBANK As-Salt r Tel Aviv 32°N r Amman e Ramla i t Ramallah d ! Ariha e M Jerusalem ! Betlehem Dead Gaza City Sea GAZAGAZA STRIPSTRIP Beersheba JORDANJORDAN Al Karak El'Arish 31°N ISRAELISRAEL At Tafilah Qa El Jinz EGYPTEGYPT Ma'an 30°N 0 20406080100Km Sources: VMAP0; RWDB, DPKO. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement by the United Nations. UNEP PCDMB - 2009 Environmental Assessment of the Gaza Strip 7 Map 2. Gaza Strip ° West Bank Erez Crossing Point a Ï" e Gaza North Jordan S Israel Beit Lahiya Jabaliyah Beit Hanoun n Beach Jabalia a ] e n Gaza Gaza a r r Ï" e Nahal Oz t Ï" i Karni Crossing Point d e M Nusayrat Al Burayj Shaykh al Maghazi MiddleDayr Area al Balah Deir al Balah Khan Yunis IsraelIsrael Khan Yunus Khan Yunis Rafah Rafah Legend p Airport Rafah Port ] Ï" Checkpoints Main roads " Rafah Ï" Ï Crossing Point p Sufa Crossing Point Landuse/Landcover Former Israeli settlements EgyptEgypt (disengaged in 2005) Ï" UNRWA Camps Kerem Shalom Crossing Point Urban Area Natural reserve 0246810Km Sources:Sources: OCHA,OCHA, UNWRA, UNWRA, GIST,GIST, PEQA, PEQA, UNOSAT.UNOSAT. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement by the United Nations.