Building a Preservation Ethic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 6

NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each itsvn-frv rr|rirlr ng """ in *hn '|| '"I"' ' '""V or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, en For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instr continuation sheets (Form 10- 900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Greyfield t/^ other names/site number Greyfield Inn 2. Location street & number city, town Cumberland Island (N/A) vicinity of county Camden code GA 039 state Georgia code GA zip code 31558 (N/A) not for publication 3. Classification Ownership of Property: Category of Property: (X) private ( ) building(s) ( ) public-local (X) district ( ) public-state ( ) site ( ) public-federal ( ) structure ( ) object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributinq buildings 6 7 sites 0 0 structures 4 2 objects 0 0 total 10 9 Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 1 Name of previous listing: The Main Road on Cumberland Island, including the part through the Greyfield property, was listed in the National Register on February 13, 1984 as part of the "Cumberland Island National Seashore Multiple Resource Area" nomination. Name of related multiple property listing: Cumberland Island National Seashore Multiple Resource Area 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Lands Legacy Tour, Cumberland Island National

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Cumberland Island National Seashore Lands and Legacies Tour Survey Fall 2012 Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2013/695 ON THE COVER Lands and Legacies Tour Photographs courtesy of Cumberland Island National Seashore Cumberland Island National Seashore Lands and Legacies Tour Survey Fall 2012 Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2013/695 Lena Le Park Studies Unit Visitor Services Project College of Natural Resources University of Idaho 875 Perimeter Drive MS 1139 Moscow, ID 83844-1139 July 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado Cumberland Island National Seashore – VSP Lands and Legacies Tour Survey 5008.2 09/25 to 11/14, 2012 The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. Data in this report were collected and analyzed using methods based on established, peer- reviewed protocols and were analyzed and interpreted within the guidelines of the protocols. -

Full Size Cumberland Island Trail

The Georgia Conservancy Y O The Georgia Conservancy’s C U N R 230 Peachtree St. NE, Suite 1250 A P V A “Cumberland Island has the greatest abundance of riches that I’ve ever S R T Atlanta, GA 30303 E S I S N Y encountered. These riches are both immediate and subtle, from the sights O O C U R A I Georgia Conservancy Coastal Office P G R R and smells of the marshlands, forests, ocean and ruins to the sounds E O S E E G N Cumberland Island T 428 Bull Street, Suite 210 that call to you once on the island. These sounds represent the voices of Savannah, GA 31401 both natural and cultural riches found on the island. I look forward to hearing those welcoming voices, calling me back, time and time again.” The Georgia Conservancy is a statewide, Become a member of the National Seashore member-supported conservation organization. Georgia Conservancy today: Our Mission: To protect and conserve georgiaconservancy.org – Suzanne Lewis, former superintendent of Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks Georgia’s natural resources through advocacy, Trail Map engagement and collaboration. #thisismyga The Trails 30°50'0” N 81°27'0” W Ashley Pond Trail Dungeness Trail Nightingale Trail Pratts Trail South End Trail Willow Pond Trail Distance - 1.8 mi. Distance - 1.5 mi. Distance - 0.8 mi. Distance - 1.1 mi. Distance - 1.7 mi. Distance - 2.1 mi. Ashley Pond Trail runs from the Main Road to the north Dungeness Trail, a mix of road, boardwalk and path, is one of Nightingale Trail is an excellent avenue to step off the Main Pratts Trail is a 1.1 mile long trail running from the Main South End Trail is a beautiful trail located on the Willow Pond is one of the most comprehensive trails on end of Table Point Trail. -

Wilderness, Wildness, and Visitor Access to Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia

WILDERNESS, WILDNESS, AND VISITOR ACCESS TO CUMBERLAND ISLAND NATIONAL SEASHORE, GEORGIA Ryan L. Sharp a feeling of isolation and wonder. These ideals, set Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources against the backdrop of the National Park Service’s University of Georgia (NPS) mission of protecting the natural character of Athens, GA 30602 the park while accommodating the recreation needs of [email protected] visitors, cause some conflicts of interest (NPS 2007). The island has been inhabited for approximately 4,000 Craig A. Miller years and had been home to wealthy industrialists Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, since the late 9th century. Human impacts on the University of Georgia island are obvious, but Cumberland has recovered from years of grazing and farming to such an extent that almost half of the island is now a federally Abstract .—Cumberland Island National Seashore designated “wilderness.” Imposing a low limit on daily (CUIS), located off the coast of Georgia, was visitors to CUIS over the past 30 years (a maximum of created in 972 to preserve the island’s ecosystem 300 people per day) has helped the island recover even and primitive character. CUIS management staff further, resulting in a mostly pristine environment. has recently been charged with developing a Transportation Management Plan (TMP) to provide Although Cumberland Island has remained relatively better access to the northern portion of the island, unchanged throughout the tenure of the NPS, CUIS where several sites of historical significance are now faces some significant changes. The original located. This assignment has created a conflict “wilderness” designation meant that a portion of the between providing transportation and preserving the main road that runs the length of the island is off-limits island’s naturalness. -

Spatial and Temporal Assessment of Back-Barrier Erosion on Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, 2011–2013

Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Spatial and Temporal Assessment of Back-Barrier Erosion on Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, 2011–2013 Scientific Investigations Report 2016 – 5071 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Back-barrier erosion as seen from Brickhill Bluff, Cumberland Island National Seashore. Photograph by Alan M. Cressler, U.S. Geological Survey. Spatial and Temporal Assessment of Back-Barrier Erosion on Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, 2011–2013 By Daniel L. Calhoun and Jeffrey W. Riley Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Scientific Investigations Report 2016 – 5071 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://store.usgs.gov/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Calhoun, D.L., and Riley, J.W., 2016, Spatial and temporal assessment of back-barrier erosion on Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, 2011–2013: U.S. -

Notes to Pages 2–16

Abbreviations and Short Citations CINS Cumberland Island National Seashore, St. Marys, Ga. CPSU Cooperative Park Studies Unit DSC Denver Service Center of the National Park Service, Denver Ga. Archives Georgia Archives, Atlanta NA National Archives, College Park, Md. NPS National Park Service SERO Southeast Regional Office of the National Park Service, Atlanta Thornton Morris Papers Thornton Morris Papers, Morris Law Firm, Atlanta UGa University of Georgia, Athens Introduction 1. The concept of “biography of place” is a useful means by which historical geographers focus on place as a complex entity formed by diverse processes that dynamically changes through time. An early example of this term’s use can be found in Marwyn S. Samuels, 1979, “The Biography of Landscape,” in Ordinary Places, ed. Donald W. Meinig (New York: Oxford Univ. Press), 51–88. Later works include William Wyckoff, 1988, The Developer’s Frontier: The Making of the West- ern New York Landscape (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press), and Gay M. Gomez, 1998, A Wetland Biography: Seasons on Louisiana’s Chenier Plain (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press). 2. A voluminous literature exists on the national park system and its man- agement. Classic overviews include Ronald A. Foresta, 1984, America’s National Parks and Their Keepers (Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future); Alfred Runte, 1987, National Parks: The American Experience, 2d ed. (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press); Richard West Sellars, 1997, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press); and Conrad L. Wirth, 1980, Parks, Politics, and People (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press). More specific works on managing preexisting land uses, private holdings, and park threats include John C. -

Hclassification

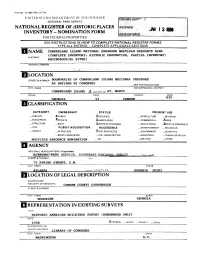

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM m is FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME CUMBERLAND ISLAND NATIONAL SEASHORE MUIiTIPLE RESOURCE AREA (COMPLETE INVENTORY: HISTORIC PROPERTIES, PARTIAL INVENTORY: HISTORIC ARCHE&EOGICAL SITES) AND/OR COMMON STREET & NUMBER AS DEFINED BY CONGRESS —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CUMBERLAND ISLAND _X . VICINITY OF ST. MARYS STATE CODE COUNTY CODE GP.ORGIA 13 CAMDEN ° 39 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XPUBLIC .^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE -XUNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _?PARK _ STRUCTURE —BOTH -XWORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL J&PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS -XYES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED _ INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION MULTIPLE RESOURCE NOMINATION _NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) -SERVICE-, STRETT& NUMBER 75 SPRING STREET, S.W. CITY. TOWN STATE ATLANTA VICINITY OF GEORGIA 30303 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. CAMDEN COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE WOODBINE GEORGIA REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY (DUNGENESS ONLY) DATE 1958 XFEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CITY. TOWN STATE WASHINGTON D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE *L.E4BBRNl» ' HH|» ^DETERIORATED ^.UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE ?LGOOD BRUINS FALTERED MOVED DATF ?LFAIR ^LUNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Cumberland Island National Seashore Multiple Resource Area includes all of the property on Cumberland Island owned by the National Park Service (see map). -

CMS Opinion Template

[PUBLISH] IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FILED U.S. COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ________________________ JUNE 28, 2004 THOMAS K. KAHN No. 03-15346 CLERK ________________________ D. C. Docket No. 02-00093-CV-AAA-2 WILDERNESS WATCH AND PUBLIC EMPLOYEES FOR ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY, Plaintiffs-Appellants, versus FRAN P. MAINELLA, Director, National Park Service, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, ARTHUR FREDERICK, Superintendent, Cumberland Island National Seashore, GREYFIELD INN CORP., Defendants-Appellees. ________________________ Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Georgia _________________________ (JUNE 28, 2004) Before BARKETT and KRAVITCH, Circuit Judges, and FORRESTER*, District Judge. *Honorable J. Owen Forrester, United States Senior District Judge for the Northern District of Georgia, sitting by designation. BARKETT, Circuit Judge: Wilderness Watch appeals the grant of summary judgment to the National Park Service on its complaint seeking to enjoin the Park Service’s practice of using motor vehicles to transport visitors across the designated wilderness area on Cumberland Island, Georgia. Wilderness Watch asserts that this practice violates the Wilderness Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1131-36, and also that the Park Service made the decision to transport tourists without conducting the investigation and analysis of potential environmental impact required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), 42 U.S.C. §§ 4331-35. Finally, Wilderness Watch claims that the Park Service established an advisory committee without the public notice and participation required by the Federal Advisory Committee Act, 5 U.S.C. App. 2, rendering the agreement signed following those meetings invalid and unenforceable.1 We review de novo a grant of summary judgment, applying the same legal standards used by the district court. -

@ Cumberland Island National Seashore

@ Cumberland Island National Seashore A History of Conservation Conflict Lary M. Dilsaver University of Virginia Press Charlottesville & London © 2004 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper First published 2004 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dilsaver, Lary M. Cumberland Island National Seashore : a history of conser- vation conflict / Lary M. Dilsaver. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-8139-2268-2 (alk. paper) 1. Cumberland Island National Seashore (Ga.)—History. 2. Cumberland Island National Seashore (Ga.)—Manage- ment. 3. Conservation of natural resources—Georgia— Cumberland Island National Seashore. 4. Cumberland Island National Seashore (Ga.)—Environmental conditions. 5. Environmental protection—Georgia—Cumberland Island National Seashore. I. Title. f292.c94 d55 2004 975.8'746—dc22 2003019677 This book is published in association with the Center for American Places, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Staunton, Virginia (www.americanplaces.org). List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1A Richness of Resources: Cumberland Island to 1880 8 2 The Era of Rich Estates, 1881–1965 36 3 Creating Cumberland Island National Seashore 76 4 Land Acquisition and Retained Rights 111 5 Planning and Operating in the 1970s 137 6Resource Management in the 1970s 165 7Contested Paradise: The 1980s and Early 1990s 195 8Hope for the New Century 239 Conclusion 260 National Park Service Officials 267 Cumberland Island National Seashore Operating Base Budgets 269 Notes 271 Index 309 Figures Figure credits: Figs. .1, 1.3, 2.1-2, 2.8, 3.1-3, 5.3, 6.2, and 8.2 are from the U.S. -

Whose Sacred Place? Planning Conflict at Cumberland Island National Seashore

202 Whose Sacred Place? Planning Conflict at Cumberland Island National Seashore Lary Dilsaver he American national park system consists of legally defined re- serves managed within a web of laws and policies. The parks also T are cultural constructs, sites where valued places and resources are preserved for future generations. As such, they have always been open to interpretation and to a division of public opinion about what is worthy of protection, what activities should occur in such “sacred places,” and who should make decisions regarding their future. Public idealism, National Park Service tradition, and threats from surrounding land uses make the parks contested landscapes where a democratic population imprints its beliefs on the land. Historical geographers are part of a growing cadre of scholars who study the meaning and management of the national park system. Ronald Foresta has provided a trenchant analysis of the National Park Service and its management policies in National Parks and Their Keepers.1 Lary Dilsaver has studied management of overcrowding, Dilsaver and William Tweed have studied National Park Service relations with concessionaires, and Dilsaver and William Wyckoff have examined the process of overdevelop- ment. Stanford Demars focused on Yosemite National Park to demon- strate the effects of such crowding. Michael Yochim has written on at- tempts to build dams and the historical geography of snowmobiles in Yellowstone National Park. Michael Conzen and Edward Muller have stud- ied the complexities of national heritage areas at the Illinois and Michigan Canal and Rivers of Steel sites respectively.2 The meaning of national parks also has been a popular subject. -

Hearing Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

S. HRG. 108–278 KATE MULLANY SITE; AMEND THE ANILCA; CONNECTICUT RIVER WATERSHED; AND CUM- BERLAND ISLAND WILDERNESS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 1241 S. 1433 S. 1364 S. 1462 OCTOBER 30, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 91–435 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:54 Jan 27, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\DOCS\91-435 SENERGY3 PsN: SENE3 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico, Chairman DON NICKLES, Oklahoma JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BOB GRAHAM, Florida LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota JAMES M. TALENT, Missouri MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana CONRAD BURNS, Montana EVAN BAYH, Indiana GORDON SMITH, Oregon DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JIM BUNNING, Kentucky CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JON KYL, Arizona MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ALEX FLINT, Staff Director JUDITH K. PENSABENE, Chief Counsel ROBERT M. SIMON, Democratic Staff Director SAM E. FOWLER, Democratic Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming, Chairman DON NICKLES, Oklahoma, Vice Chairman BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado DANIEL K. -

Hope for the New Century

@8 Hope for the New Century Going into the last five years of the twentieth century, National Park Service officials still sought closure for four types of problems. Natural resource managers needed to expand their research and monitoring of coastal erosion as well as resolve the question of feral animals. Historic preservation suffered not only from a woeful short- age of funds but also disagreement over the priority of cultural resources. Private landholders still controlled several critical island-straddling private plots while the limits of retained rights remained vague. Finally, Cumber- land Island National Seashore desperately needed a wilderness plan. The level of conflict between various interest groups grew more emotional and vicious with each passing year. The agency’s reactive and somewhat erratic management faced almost certain lawsuits over the wilderness in the near future. Designing a wilderness plan in the midst of such acrimony was a for- bidding prospect. Superintendent Rolland Swain understated the complex- ity of wilderness planning when he noted that “it is almost certain to be difficult and contentious.”1 Unfortunately, events during 1995 and 1996 crushed the hard-won opti- mism of the early 1990s. In each management area the National Park Ser- vice saw its plans and proposals unravel in the face of renewed public criti- cism and the worst interest-group conflict in the history of the seashore. Yet as the new century dawned, the agency reevaluated the Cumberland legis- lation and retained-rights pacts and decided to plow ahead with wilderness planning. At the same time, many seashore officials reluctantly admitted that only a court of law or Congress could settle the myriad problems of Cumberland Island National Seashore.