Financial Stability Board Proposes TLAC Requirements for G-Sibs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

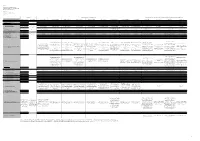

Basel III: Post-Crisis Reforms

Basel III: Post-Crisis Reforms Implementation Timeline Focus: Capital Definitions, Capital Focus: Capital Requirements Buffers and Liquidity Requirements Basel lll 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 2027 1 January 2022 Full implementation of: 1. Revised standardised approach for credit risk; 2. Revised IRB framework; 1 January 3. Revised CVA framework; 1 January 1 January 1 January 1 January 1 January 2018 4. Revised operational risk framework; 2027 5. Revised market risk framework (Fundamental Review of 2023 2024 2025 2026 Full implementation of Leverage Trading Book); and Output 6. Leverage Ratio (revised exposure definition). Output Output Output Output Ratio (Existing exposure floor: Transitional implementation floor: 55% floor: 60% floor: 65% floor: 70% definition) Output floor: 50% 72.5% Capital Ratios 0% - 2.5% 0% - 2.5% Countercyclical 0% - 2.5% 2.5% Buffer 2.5% Conservation 2.5% Buffer 8% 6% Minimum Capital 4.5% Requirement Core Equity Tier 1 (CET 1) Tier 1 (T1) Total Capital (Tier 1 + Tier 2) Standardised Approach for Credit Risk New Categories of Revisions to the Existing Standardised Approach Exposures • Exposures to Banks • Exposure to Covered Bonds Bank exposures will be risk-weighted based on either the External Credit Risk Assessment Approach (ECRA) or Standardised Credit Risk Rated covered bonds will be risk Assessment Approach (SCRA). Banks are to apply ECRA where regulators do allow the use of external ratings for regulatory purposes and weighted based on issue SCRA for regulators that don’t. specific rating while risk weights for unrated covered bonds will • Exposures to Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) be inferred from the issuer’s For exposures that do not fulfil the eligibility criteria, risk weights are to be determined by either SCRA or ECRA. -

Reducing Procyclicality Arising from the Bank Capital Framework

Joint FSF-BCBS Working Group on Bank Capital Issues Reducing procyclicality arising from the bank capital framework March 2009 Financial Stability Forum Joint FSF-BCBS Working Group on Bank Capital Issues Reducing procyclicality arising from the bank capital framework This note sets out recommendations to address the potential procyclicality of the regulatory capital framework for internationally active banks. Some of these recommendations are focused on mitigating the cyclicality of the minimum capital requirement, while maintaining an appropriate degree of risk sensitivity. Other measures are intended to introduce countercyclical elements into the framework. The recommendations on procyclicality form a critical part of a comprehensive strategy to address the lessons of the crisis as they relate to the regulation, supervision and risk management of internationally active banks. This strategy covers the following four areas: Enhancing the risk coverage of the Basel II framework; Strengthening over time the level, quality, consistency and transparency of the regulatory capital base; Mitigating the procyclicality of regulatory capital requirements and promoting the build up of capital buffers above the minimum in good economic conditions that can be drawn upon in stress; and Supplementing the capital framework with a simple, non-risk based measure to contain the build up of leverage in the banking system. The objective of these measures is to ensure that the Basel II capital framework promotes prudent capital buffers over the credit cycle and to mitigate the risk that the regulatory capital framework amplifies shocks between the financial and real sectors. As regulatory capital requirements are just one driver of bank lending behaviour, the proposals set out should be considered in the wider context of other measures to address procyclicality and reduce systemic risk. -

Pillar 3 (Basel Iii) Disclosures As on 31.03.2021 Central Bank of India

PILLAR 3 (BASEL III) DISCLOSURES AS ON 31.03.2021 CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA Table DF-1: Scope of Application (i) Qualitative Disclosures: The disclosure in this sheet pertains to Central Bank of India on solo basis. In the consolidated accounts (disclosed annually), Bank‟s subsidiaries/associates are treated as under a. List of group entities considered for consolidation Name of the Whether the Explain the Whether the Explain the Explain the Explain the entity / Country entity is method of entity is method of reasons for reasons if of incorporation included consolidation included consolidation difference in consolidated under under the method under only one accounting regulatory of of the scopes scope of scope of consolidation of consolidation consolidation consolidation (yes / no) (yes / no) Cent Bank Yes Consolidatio Yes NA NA NA Home Finance n of the Ltd./ India financial statements of subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 21. Cent Bank Yes Consolidatio Yes NA NA NA Financial n of the Services financial Ltd./India statements of subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 21 Uttar Bihar Yes Consolidatio No NA NA Associate: Gramin Bank, n of the Not under Muzzaffarpur/ financial scope of regulatory India statements of Consolidation subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 23 1 Uttar Banga Yes Consolidatio No NA NA Associate: Kshetriya n of the Not under Gramin Bank, financial scope of regulatory Cooch Behar/ statements of Consolidation India subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 23 Indo-Zambia Yes Consolidatio No NA NA Joint Bank Ltd. n of the Venture: Not /Zambia. financial under scope of regulatory statements of Consolidation subsidiaries in accordance with AS- 23 b. -

Navigating Through the Pandemic from a Position of Strength

Navigating Through the Pandemic from a Position of Strength Citi’s Commitment Supporting ICG Clients And Customers During these uncertain times, Citi remains well- Our ICG colleagues are working around the clock We are actively supporting our consumer clients positioned from a capital and liquidity to help our institutional clients navigate volatile through this unprecedented time. perspective. markets and manage their business needs as the • We continue to serve our customers while taking We have a strong balance sheet and will continue economic impacts of the pandemic continue to measures to help reduce the spread of COVID-19. to actively support our clients and customers evolve. As such, we have temporarily adjusted branch hours through this challenging period. • In BCMA, we continue lending to companies in and closed some locations. greatly affected industries, including airlines, leisure, • We were one of the first banks to announce industrials, autos and energy. We are helping blue assistance measures for impacted consumers and Key Financial Metrics chip multinationals strengthen their liquidity positions small businesses in the U.S. and are presenting clients with additional options to • Citibank's individual and Small Business customers (As of September 30, 2020) equitize and monetize. We are proud to work closely impacted by COVID-19 may be eligible for the Managing well through this crisis year-to-date with governments and the public sector to find following assistance measures, upon request. liquidity alternatives and have been working on the • Significant earnings power with ~$7B of net issuance of social bonds to support countries in the - Retail Bank: Fee waivers on monthly service income, despite ~$11B increase in credit Emerging Markets. -

Financial Risk&Regulation

Financial Risk&Regulation Sustainability in finances – opportunities and regulatory challenges Newsletter – March 2021 In addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, last year has been characterized by a green turnaround that involved the financial sector as well. Sustainability factors are increasingly integrated into the regulatory expectations on credit institutions and investment service providing firms, as well as new opportunities provided by capital requirement reductions. In addition to a number of green capital requirement reductions, the Hungarian National Bank (MNB) recently issued a management circular on the adequacy of the Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) applicable from March 10. In our newsletter, we cover these two topics. I. Green Capital Requirement Discount construction the real estate should have an energy for Housing rating of “BB” or better. In course of modernization the project should include at least one modernization In line with the EU directive and in addition to the measure specified by the MNB (e.g. installation of “green finance” program of several other central solar panels or solar collectors, thermal insulation, banks, MNB also announced its Green Program facade door and window replacement). In the in 2019, which aimed to launch products for the case of a discounted loan disbursed this way, the Hungarian financial sector that support sustainability, central bank imposes lower capital requirement on and to mobilize the commercial banks and disbursing institutions, if the interest rate or the APR investment funds. All this is not only of ecological (THM) on the “green” loan is at least 0.3 percentage significance: under the program, banks can move points more favourable (compared to other similar towards the “green” goals by reducing their credit products). -

Revised Standards for Minimum Capital Requirements for Market Risk by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (“The Committee”)

A revised version of this standard was published in January 2019. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d457.pdf Basel Committee on Banking Supervision STANDARDS Minimum capital requirements for market risk January 2016 A revised version of this standard was published in January 2019. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d457.pdf This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2015. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISBN 978-92-9197-399-6 (print) ISBN 978-92-9197-416-0 (online) A revised version of this standard was published in January 2019. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d457.pdf Minimum capital requirements for Market Risk Contents Preamble ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Minimum capital requirements for market risk ..................................................................................................................... 5 A. The boundary between the trading book and banking book and the scope of application of the minimum capital requirements for market risk ........................................................................................................... 5 1. Scope of application and methods of measuring market risk ...................................................................... 5 2. Definition of the trading book .................................................................................................................................. -

Capital Adequacy Regulation (CAR)

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Central Bank of Myanmar Notification No. (16/2017) 14th Waxing Day of Waso 1379 ME July 7, 2017 ------------------------------------------------- In exercise of the powers conferred under Sections 34 and 184 of the Financial Institutions Law, the Central Bank of Myanmar hereby issues the following Regulations: 1. These Regulations shall be called Capital Adequacy Regulation (CAR). 2. These Regulations shall apply to all banks. 3. Capital Adequacy Ratio is a measure of the amount of a bank’s capital expressed as a percentage of its risk weighted assets. Banks are required to maintain the Capital Adequacy Ratio as follows: (a) Regulatory capital adequacy ratio is 8%; (b) The minimum Tier I Capital Adequacy Ratio is 4%. (c) In meeting the capital adequacy ratio, elements of Tier 2 or supplementary capital, may be included subject to approval of the Central Bank of Myanmar up to a maximum of 100% of Tier 1 or core capital. 4. A bank may increase its paid up capital by- (a) amendment to its constituent documents approved by the general meeting of the shareholders; and (b) the written approval of the Central Bank of Myanmar. 5. The initial paid-up capital and any subsequent increases in paid up capital must be deposited at the Central Bank of Myanmar. Subsequent to verification by the Central Bank of Myanmar, the bank may move the funds to their account. 6. Every bank must report the position of capital and capital adequacy ratio at the end of each month in the attached form to the Banking Supervision Department of the Central Bank of Myanmar. -

Capital-Instruments-Key-Features-Table

Capital instruments of UBS Group AG (consolidated) and UBS AG (consolidated and standalone) as of 31 March 2016 Key features Ordered by issuance date within each category Based on Swiss SRB Basel III phase-in requirements Issued on 4 May 2016 Share capital Additional Tier 1 capital instruments (Basel III compliant) Additional Tier 1 capital / Tier 2 capital instruments in the form of hybrid instruments and related subordinated notes (non-Basel III compliant) UBS Group AG, Switzerland, or other employing UBS Group AG, Switzerland, or other UBS Preferred Funding Trust IV UBS AG, Switzerland UBS Preferred Funding Trust V UBS AG, Switzerland 1 Issuer (country of incorporation; if applicable, branch) UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS AG, Switzerland UBS Group AG, Switzerland UBS AG, Switzerland entities of the Group employing entities of the Group Delaware, US Cayman branch Delaware, US Cayman branch 1a Instrument number 001 002 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 010 011 012 013 014 015 2 Unique identifier (e.g. ISIN) ISIN: CH0244767585 ISIN: CH0024899483 - ISIN: CH0271428309 ISIN: CH0271428317 ISIN: CH0271428333 ISIN: CH0286864027 - - ISIN: CH0317921697 - ISIN: US90263W2017 - ISIN: US90264AAA79 - 3 Governing law(s) of the instrument Swiss Swiss Swiss / NY, US Swiss law Swiss law Swiss law Swiss law Swiss law Swiss / NY, US Swiss law Swiss law Delaware, US NY, US Delaware, US NY, US Regulatory treatment 4 Transitional Basel III -

Basel III Regulatory Capital Disclosures March 31, 2021

Huntington Bancshares Incorporated Basel III Regulatory Capital Disclosures March 31, 2021 Huntington Bancshares Incorporated Basel III Regulatory Capital Disclosures Glossary of Acronyms Acronym Description ACL Allowance for Credit Losses AFS Available For Sale ALLL Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses BHC Bank Holding Company BHC Act Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 C&I Commercial and Industrial CCAR Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review CAP Capital Adequacy Process CECL Current Expected Credit Losses COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019 CRE Commercial Real Estate EAD Exposure At Default Federal Reserve Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System FRB Federal Reserve Board GAAP Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in the United States HTM Held to Maturity HVCRE High Volatility Commercial Real Estate ISDA International Swaps and Derivatives Association MD&A Management Discussion and Analysis MDB Multilateral Development Bank OTC Over-The-Counter PFE Potential Future Exposure PSE Public Sector Entity RWA Risk Weighted Assets SPE Special Purpose Entity SSFA Simplified Supervisory Formula Approach T-Bill Treasury Bill T-Bond Treasury Bond T-Note Treasury Note VIE Variable Interest Entity March 31, 2021 Page 2 Huntington Bancshares Incorporated Basel III Regulatory Capital Disclosures Introduction Company Overview Huntington Bancshares Incorporated ("Huntington" or "HBI") is a multi-state diversified regional bank holding company organized under Maryland law in 1966 and headquartered in Columbus, Ohio. Huntington has 15,449 average full-time equivalent employees. Through its bank subsidiary, The Huntington National Bank, HBI has over 150 years of serving the financial needs of our customers. Through its subsidiaries, including the Bank, Huntington provides full-service commercial and consumer banking services, mortgage banking services, automobile financing, recreational vehicle and marine financing, equipment financing, investment management, trust services, brokerage services, insurance products and services, and other financial products and services. -

Commercial Bank Examination Manual, Section 3000

3000—CAPITAL, EARNINGS, LIQUIDITY, AND SENSITIVITY TO MARKET RISK The 3000 series of sections address the super- asset quality (see the 2000 series major head- visory assessment of a state member bank’s ing), the CELS components represent the key Capital, Earnings, Liquidity, and Sensitivity to areas that examiners review in assessing the market risk (CELS). In addition to the review of overall financial condition of the bank. Commercial Bank Examination Manual May 2021 Page 1 Assessment of Capital Adequacy Effective date November 2020 Section 3000.1 PURPOSE OF CAPITAL financial crisis by helping to ensure that the banking system is better able to absorb losses Although both bankers and bank regulators look and continue to lend in future periods of eco- carefully at the quality of bank assets and nomic stress. In addition, Regulation Q imple- management and at the ability of the bank to ments certain federal laws related to capital control costs, evaluate risks, and maintain proper requirements and international regulatory capi- liquidity, capital adequacy is the area that trig- tal standards adopted by the Basel Committee gers the most supervisory action, especially in on Banking Supervision (BCBS). view of the prompt-corrective-action (PCA) pro- vision of section 38 of the Federal Deposit Applicability of Regulation Q Insurance Act (FDIA), 12 U.S.C. 1831o. The primary function of capital is to fund the bank’s Regulation Q applies on a consolidated basis to operations, act as a cushion to absorb unantici- every Board-regulated institution (referred to as pated losses and declines in asset values that a “banking organization” in this section) that is may otherwise lead to material bank distress or failure, and provide protection to uninsured • a state member bank; depositors and debt holders if the bank were to • a bank holding company (BHC) domiciled in be placed in receivership. -

The Welfare Cost of Bank Capital Requirements

THE WELFARE COST OF BANK CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS Skander Van den Heuvel1 The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania December, 2005 Abstract This paper measures the welfare cost of bank capital requirements and finds that it is surprisingly large. I present a simple framework which embeds the role of liquidity creating banks in an otherwise standard general equilibrium growth model. A capital requirement plays a role, as it limits the moral hazard on the part of banks that arises due to the presence of a deposit insurance scheme. However, this capital requirement is also costly because it reduces the ability of banks to create liquidity. A key result is that equilibrium asset returns reveal the strength of households’ preferences for liquidity and this allows for the derivation of a simple formula for the welfare cost of capital requirements that is a function of observable variables only. Using U.S. data, the welfare cost of current capital adequacy regulation is found to be equivalent to a permanent loss in consumption of between 0.1 to 1 percent. 1 Finance Department, Wharton School, 3620 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA. Email: [email protected]. The author especially thanks Andy Abel and Joao Gomes for detailed comments and suggestions, as well as Franklin Allen, John Boyd, Marty Eichenbaum, Gary Gorton, Stavros Panageas, Amir Yaron and seminar participants at the FDIC, the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia and San Francisco, the NBER Summer Institute, the Society for Economic Dynamics and Wharton, for helpful suggestions. Sungbae An, Itamar Drechsler and Nicolaas Koster provided excellent research assistance. -

Regulatory Capital and Risk Management Pillar 3 Disclosures

2021 HSBC Bank Canada Regulatory Capital & Risk Management Pillar 3 Supplementary Disclosures As at March 31, 2021 HSBC Bank Canada Pillar 3 Supplementary Disclosure First Quarter 2021 1 Contents Page Notes to users 3 Road map to Pillar 3 disclosures 4 Capital and RWA 5 Regulatory Capital Disclosure - CC1 5 Overview of Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) - OV1 6 Credit Risk 6 RWA flow statements of credit risk exposures under IRB - CR8 6 Market Risk 6 RWA flow statements of market risk exposures under an Internal Model Approach (IMA) - MR2 7 Leverage Ratio 7 Summary comparison of accounting assets vs. leverage ratio exposure measure (LR1) 7 Leverage Ratio Common Disclosure (LR2) 8 Glossary 9 2 HSBC Bank Canada Pillar 3 Supplementary Disclosure First Quarter 2021 Notes to users Regulatory Capital and Risk Management Pillar 3 Disclosures The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (“OSFI”) supervises HSBC Bank Canada (the “Bank”) on a consolidated basis. OSFI has approved the Bank’s application to apply the Advanced Internal Ratings Based (“AIRB”) approach to credit risk on our portfolio and the Standardized Approach for measuring Operational Risk. Please refer to the Annual Report and Accounts 2020 for further information on the Bank’s risk and capital management framework. Further information regarding HSBC Group Risk Management Processes can be found in HSBC Holdings plc Capital and Risk Management Pillar 3 Disclosures available on HSBC Group’s investor relations web site. The Pillar 3 Supplemental Disclosures are additional summary