The Music Folder #1 Alvin Curran Interview by Veniero Rizzardi, Milan 21 November 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rodriguez, Luz

Voices of Feminism Oral History Project Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Northampton, MA LUZ RODRIGUEZ Interviewed by JOYCE FOLLET June 16 - 17, 2006 Northampton, Massachusetts This interview was made possible with generous support from the Ford Foundation. © Sophia Smith Collection 2006 Sophia Smith Collection Voices of Feminism Oral History Project Narrator Luz Marina Rodriquez was born in New York City on March 7, 1956, and grew up on the Lower East Side. She was the eldest of three children of Elsa Rodriguez Vazquez and Luis Rodriguez Nieto, Sr., who had both recently migrated from Puerto Rico as part of Operation Bootstrap. Her father held a variety of jobs, including electronics repair and night security work, while her mother worked as an Avon Lady. After graduating from Seward Park High School in 1974, Rodriguez spent two years immersed in social and cultural activities in her Puerto Rican neighborhood, which became known as Loisaida. She was deeply involved in The Real Great Society, a gang outreach and community empowerment organization created in 1964 to engage youth in addressing local needs, especially sweat equity projects to create affordable housing. She was also an active participant in CHARAS/El Bohio, a cultural center where she taught Puerto Rican folkloric dance. After studying dance at Pratt Institute, Rodriguez graduated from NYU as a dance therapy major in 1982. College research into the sterilization and birth control experimentation on Puerto Rican women planted the seed of later reproductive rights activism. Rodriguez defines herself as a servant-leader. She has continued to combine grassroots social justice work with administrative leadership in non-profit organizations, including Henry Street Settlement, Lower East Side Family Resource Center, Dominican Women’s Development Center, and Casa Atabex. -

The Children of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre. Tony Earnest Medlin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Medlin, Tony Earnest, "The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7281. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Richard Teitelbaum

RICHARD TEITELBAUM . f lectro-Acoustic Chamber Music February 27-28, 1979 8:30pm $3.50 / $2.00 members / TDF Music The Kitchen Center 484 Broome Street On February 27- 28, The Kitchen Center will present works by Richard Teitel baum. Performers of the compositions and improvisations on the program include George Lewis, trombone and electronics; Reih i Sano, shakuhachi; and Richard Teitel baum, Pol yMoog, MicroMoog and modular Moog synthesizers. The program of electro-acoustic chamber music opens with "Blends," a piece for shakuhachi and synthesizers featuring the playing of Reihi Sano. The piece was composed and first per- formed in 1977, while Teitelbaum was studying in Japan on a Fullbright scholarship. Reihi Sano, who is currently an artist-in-residence at Wesleyan University, has a virtuoso command of the shakuhachi, the endblown bamboo flute. This performance of "Blends" is an American premiere. Similarly, a new work with George Lewis, incorporates Lewis's prodigious com- mand of the trombone and live electronics in a semi-improvisational piece. George Lewis has been involved with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians since 1971, and has played with musicians as diverse as Anth0n.y Braxton, Phil Niblock and Count Basie, in addition to studying philosophy at Yale University. Teitelbaum and Lewis have played at Axis In SoHo, Studio RivBea and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. An extensive synthesizer solo by Teitelbaum, entitled "Shrine" (1976-78) rounds out the concert program. Richard Teitelbaum is one of the prime movers of live electronic music. Classically trained, and with a Master's degree in Music from Yale, he studied in Italy with Luigi Nono. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them. -

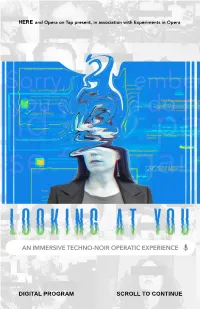

DIGITAL PROGRAM SCROLL to CONTINUE Click on Any Section Below to Jump to the Page

and Opera on Tap present, in association with Experiments in Opera DIGITAL PROGRAM SCROLL TO CONTINUE Click on any section below to jump to the page. SHOW INFO 3 BIOS 4 RESOURCES 15 DIGITAL PRIVACY KIT 15 PRODUCTION HISTORY 16 ABOUT HERE 18 MEMBERSHIP 20 HERE STAFF 21 FUNDING 22 SURVEY 25 HEREART 26 FOLLOW US 26 and Opera on Tap present, in association with Experiments in Opera Story by Rob Handel, Kristin Marting, and Kamala Sankaram Composed by Kamala Sankaram Libretto by Rob Handel Developed with, Co-Choreographed and Directed by Kristin Marting Music Direction by Samuel McCoy Performers Paul An, Adrienne Danrich, Blythe Gaissert, Eric McKeever, Mikki Sodergren, Brandon Snook, and Jorell Williams* Video Designer David Bengali Technologists Alessandro Acquisti, Ralph Gross Tablet Technologists Joe Holt, Daniel Dickison Scenic Designer Nic Benacerraf Costume Designer Kate Fry Lighting Designer Ayumu “Poe” Saegusa Choreographer Amanda Szeglowski Sound Engineer Nathaniel Butler Production Stage Manager Westie Productions Piano Mila Henry Saxophones Jeff Hudgins, Ed RosenBerg, Josh Sinton, and Matt Blanchard** Production Manager Michaelangelo De Serio Technical Director Eli Reid Assistant Costume Designer Tekla Monson Associate Video Designer Shefali Nayak Projection Animation Assistant Kathleen Fox Assistant Directors Anne Bakan, Sim Yan Ying Assistant Stage Manager/Wardrobe Manager Aoife Hough Stitcher Elise Walsh * 9/15–21 performances only ** 9/21 performances only Looking at You is made possible through the generous support of Carnegie Mellon University; Dashlane; KSF; Mental Insight Foundation; New England Foundation for the Arts; Puffin Foundation; Opera America’s Grants for Female Composers supported by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation and Opera America’s Innovation Fund supported by the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation; and the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hf4q6w5 Journal Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 1(3) Author Dessen, MJ Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 1, No 3 (2006) Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Michael Dessen, Hampshire College Introduction Throughout the twentieth century, African American improvisers not only created innovative musical practices, but also—often despite staggering odds—helped shape the ideas and the economic infrastructures which surrounded their own artistic productions. Recent studies such as Eric Porter’s What is this Thing Called Jazz? have begun to document these musicians’ struggles to articulate their aesthetic philosophies, to support and educate their communities, to create new audiences, and to establish economic and cultural capital. Through studying these histories, we see new dimensions of these artists’ creativity and resourcefulness, and we also gain a richer understanding of the music. Both their larger goals and the forces working against them—most notably the powerful legacies of systemic racism—all come into sharper focus. As Porter’s book makes clear, African American musicians were active on these multiple fronts throughout the entire century. Yet during the 1960s, bolstered by the Civil Rights -

Steve Paxton and Lisa Nelson, Night Stand, 2004.Pdf

Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton Night Stand, 2004 Dia:Chelsea 541 West 22nd Street New York City 212 989 5566 www.diaart.org Dia Art Foundation presents Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton Night Stand, 2004 Thursday, October 10–Saturday, October 12, 2013, 8 pm Thursday, October 17–Saturday, October 19, 2013, 8 pm Dance, setting, and sound compilation by Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton Lighting by Carol Mullins performers Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton production manager Adam Macks music Excerpts from Automatic Writing (1979), eL/Aficionado (1994), and Dust (2000) by Robert Ashley (Lovely Music) and Zvuki Mu (1989) by Pyotr Mamonov (Opal Records). Dia’s presentation of Night Stand marks the United States premiere. Night Stand has been previously performed at Centre chorégraphique national de Montpellier Languedoc–Roussillon, France; Marseille Objectif Danse, France; Side Step Festival, Helsinki, Finland; SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, Brazil; L’animal a l’esquena, Celrà, Spain; and Spiral Hall, Tokyo, Japan. This program is made possible in part by Dia’s Commissioning Committee: Jill and Peter Kraus, Leslie and Mac McQuown, Genny and Selmo Nissenbaum, and Liz Gerring Radke and Kirk August Radke. Front Cover: Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton, Night Stand, 2004. Performance at L’animal a l’esquena, Celrà, Spain, 2008. Photo © Jordi Bover. Progress Report: Night Stand Night Stand is the third collaboration between Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton, Paxton and Nelson’s performing partnership dates back to 1975. Paxton’s after PA RT, which they performed from 1978 to 2002, and Population, which approach to physical improvisation is sourced in an ongoing investigation of the was performed once in 1988. -

The Long Christmas Dinner Leon Botstein, Conductor

12-19 ASO_GP 12/2/14 11:22 AM Page 1 Friday Evening, December 19, 2014, at 8:00 in association with the Bard Center presents The Long Christmas Dinner Leon Botstein, Conductor The Long Christmas Dinner One-act play by Thornton Wilder Intermission The Long Christmas Dinner One-act opera by Paul Hindemith Libretto by Thornton Wilder Director: Jonathan Rosenberg Scenic Designer: Zane Pihlstrom Costume Designer: Olivera Gajic Lighting Designer: Peter West Producer: Thurmond Smithgall The play The Long Christmas Dinner is presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. The opera The Long Christmas Dinner is presented by arrangement with European American Music Distribution Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, publisher and copyright owner. Video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. This evening’s event will run approximately two hours including one 20-minute intermission. This project is made possible with the support of The Lanie & Ethel Foundation and The Wilder Family. Alice Tully Hall Please make certain your cellular phone, pager, or watch alarm is switched off. 12-19 ASO_GP 12/2/14 11:22 AM Page 2 Lincoln Center Leon Botstein Lars Berge Arielle Goldman Ryan-James Libby Matthews Hatanaka Hannah Mitchell Claire Moodey Michael Salinas Glenn Seven Allen Kathryn Guthrie Catherine Martin Scott Murphree Sara Murphy Jarrett Ott Josh Quinn Camille Zamora Leon Botstein photo by Ric Kallaher; Arielle Goldman, Ryan-James Hatanaka, and Libby Matthews photos by Deborah Lopez; Hannah Mitchell photo by Michael Medeiros; Claire Moodey photo by Commontiger Photography; Michael Salinas photo by Evan Smith; Kathryn Guthrie photo by Claire McAdams; Catherine Martin photo by Kristen Hoebermann; Jarrett Ott photo by Steve Riskind; Josh Quinn photo by Kate Lemmon Photography; Camille Zamora photo by Liron Amsellem. -

MUSICA ELETTRONICA VIVA MEV 40 (1967–2007) 80675-2 (4Cds)

MUSICA ELETTRONICA VIVA MEV 40 (1967–2007) 80675-2 (4CDs) DISC 1 1. SpaceCraft 30:49 Akademie der Kunste, Berlin, October 5, 1967 Allan Bryant, homemade synthesizer made from electronic organ parts Alvin Curran, mbira thumb piano mounted on a ten-litre AGIP motor oil can, contact microphones, amplified trumpet, and voice Carol Plantamura, voice Frederic Rzewski, amplified glass plate with attached springs, and contact microphones, etc. Richard Teitelbaum, modular Moog synthesizer, contact microphones, voice Ivan Vandor, tenor saxophone 2. Stop the War 44:39 WBAI, New York, December 31, 1972 Frederic Rzewski, piano Alvin Curran, VCS3-Putney synthesizer, piccolo trumpet, mbira thumb piano, etc. Garrett List, trombone Gregory Reeve, percussion Richard Teitelbaum, modular Moog synthesizer Karl Berger, marimbaphone DISC 2 1. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Pt. 1 43:07 April 1982 Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone Garrett List, trombone Alvin Curran, Serge modular synthesizer, piccolo trumpet, voice Richard Teitelbaum, PolyMoog and MicroMoog synthesizers with SYM 1 microcomputer Frederic Rzewski, piano, electronically-processed prepared piano 2. Kunstmuseum, Bern 24:37 November 16, 1990 Garrett List, trombone Alvin Curran, Akai 6000 sampler and Midi keyboard Richard Teitelbaum, Prophet 2002 sampler, DX 7 keyboard, Macintosh computer Frederic Rzewski, piano DISC 3 1. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Pt. 2 44:05 April 1982 Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone Garrett List, trombone Alvin Curran, Serge modular synthesizer-processing for piano and sax, piccolo trumpet, voice Richard Teitelbaum, Polymoog and MicroMoog synthesizers with SYM 1 microcomputer Frederic Rzewski, piano, electronically processed prepared piano 2. New Music America Festival 30:51 The Knitting Factory, New York, November 15, 1989 Steve Lacy, soprano saxophone Garrett List, trombone Richard Teitelbaum, Yamaha DX 7, Prophet sampler, computer with MAX/MSP, Crackle Box Alvin Curran, Akai 5000 Sampler, MIDI keyboard, flugelhorn Frederic Rzewski, piano DISC 4 1. -

It Worked Yesterday: on (Re-) Performing Electroacoustic Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Berweck, Sebastian It worked yesterday: On (re-)performing electroacoustic music Original Citation Berweck, Sebastian (2012) It worked yesterday: On (re-)performing electroacoustic music. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17540/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ It worked yesterday On (re-)performing electroacoustic music A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sebastian Berweck, August 2012 Abstract Playing electroacoustic music raises a number of challenges for performers such as dealing with obsolete or malfunctioning technology and incomplete technical documentation. Together with the generally higher workload due to the additional technical requirements the time available for musical work is significantly reduced. -

Frederic Rzewski Visits America

Frederic Rzewski Visits America A conversation with Frank J. Oteri @ Nonesuch Records, NYC On John Cage's Birthday (September 5, 2002), 1:30 PM Videotaped by Amanda MacBlane 1. Hierarchy, Power, and Pedigree 2. On Systems 3. Performing 4. Electronics and Live Music 5. Other Pianists 6. Other Ensembles and the Orchestra 7. Publishing and Recording 8. The Role of the Composer in Society 1. Hierarchy, Power, and Pedigree FRANK J. OTERI: You studied composition with a very diverse group of people whose music is very different from your own: Babbitt and Sessions, Randall Thompson, Piston, Elliott Carter… FREDERIC RZEWSKI: I never studied with Carter… FRANK J. OTERI: The Grove Dictionary says you did… FREDERIC RZEWSKI: No! FRANK J. OTERI: But you did study with Babbitt and Sessions? FREDERIC RZEWSKI: Technically, yes FRANK J. OTERI: The first pieces of yours to gain wide exposure are so different from their music, but to this day, the notion of twelve-tone composition plays a role in your work and is part of your vocabulary. FREDERIC RZEWSKI: Hard to say. I was at Harvard in the '50s and I had some teachers who were very important for me. Randall Thompson was one of the best teachers I ever had. I was in his counterpoint class at Harvard. I think in those days the school was most importantly a place where I came together with people like myself and I think that's probably the most useful function of schools in general. It's not so much a matter of studying in the sense that information is transmitted from one generation to another, but it's where under the guidance of perhaps older people it's possible to link up with people who are doing things similar to what you're doing.