CHAPTER 2 Neolithic and Bronze AGE Pembrokeshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bryn Yr Odyn Solar Park, Tyn Dryfol, Soar, Anglesey

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S The Bryn Yr Odyn Solar Park, Tyn Dryfol, Soar, Anglesey Desk-based Heritage Assessment by Steve Preston Site Code TDA13/31 (SH3950 7380) The Bryn Yr Odyn Solar Park, Tyn Dryfol, Soar, Anglesey Desk-based Heritage Assessment for New Forest Energy Ltd by Steve Preston Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code TDA13/31 April 2013 Summary Site name: The Bryn Yr Odyn Solar Park, Tyn Dryfol, Soar, Anglesey Grid reference: SH3950 7380 Site activity: Desk-based heritage assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Steve Preston Site code: TDA13/31 Area of site: 29ha Summary of results: There are no known heritage assets on the site. There are, however, two Scheduled Monuments close enough to be in a position where their settings could be affected by its development. On balance it is not considered that the nature of the proposal would adversely affect the appreciation of these monuments. The area around the site, particularly to the south and east, is comparatively rich in known archaeological sites, with several small Roman settlements besides the two Scheduled Monuments, and the speculative line of a Roman road. The site covers a very large area, increasing the probability of archaeological remains being present simply by chance. The landscape of the site has been farmland since cartographic depictions began, and most of the fields are comparatively recent constructions. The proposal overall does not obviously carry any significant adverse impacts on archaeological remains but there may be the potential for localized disturbance in areas of electricity substation or deeper cable trenches. -

2019 Fishguard Show Schedule .Indd

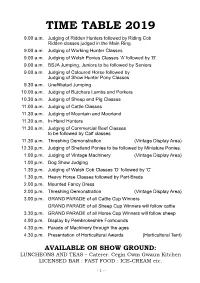

TIME TABLE 2019 9.00 a.m. Judging of Ridden Hunters followed by Riding Cob Ridden classes judged in the Main Ring. 9.00 a.m. Judging of Working Hunter Classes 9.00 a.m. Judging of Welsh Ponies Classes ‘A’ followed by ‘B’ 9.00 a.m. BSJA Jumping, Juniors to be followed by Seniors 9.00 a.m. Judging of Coloured Horse followed by Judging of Show Hunter Pony Classes 9.30 a.m. Unaffiliated Jumping 10.00 a.m. Judging of Butchers Lambs and Porkers 10.30 a.m. Judging of Sheep and Pig Classes 11.00 a.m. Judging of Cattle Classes 11.30 a.m. Judging of Mountain and Moorland 11.30 a.m. In-Hand Hunters 11.30 a.m. Judging of Commercial Beef Classes to be followed by Calf classes 11.30 a.m. Threshing Demonstration (Vintage Display Area) 12.30 p.m. Judging of Shetland Ponies to be followed by Miniature Ponies. 1.00 p.m. Judging of Vintage Machinery (Vintage Display Area) 1.00 p.m. Dog Show Judging 1.30 p.m. Judging of Welsh Cob Classes ‘D’ followed by ‘C’ 1.30 p.m. Heavy Horse Classes followed by Part-Breds 2.00 p.m. Mounted Fancy Dress 2.00 p.m. Threshing Demonstration (Vintage Display Area) 3.00 p.m. GRAND PARADE of all Cattle Cup Winners GRAND PARADE of all Sheep Cup Winners will follow cattle 3.30 p.m. GRAND PARADE of all Horse Cup Winners will follow sheep 4.00 p.m. Display by Pembrokeshire Foxhounds 4.30 p.m. -

Report No. 20/16 National Park Authority

Report No. 20/16 National Park Authority REPORT OF THE HEAD OF PARK DIRECTION SUBJECT: LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN: REGIONALLY IMPORTANT GEODIVERSITY SITES SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING GUIDANCE (SPG) Purpose of this Report 1. This report seeks approval to add an additional site to the above guidance which was adopted in October 2011 and to publish the updated guidance for consultation. Background 2. The Regionally Important Geodiversity Sites are a non-statutory geodiversity designation. The supplementary planning guidance helps to identify whether development has an adverse effect on the main features of interest within a RIGS. It is supplementary to Policy 10 ‘Local Sites of Nature Conservation or Geological Interest’. 3. Details of the new site are given in Appendix A. A map is awaited which will show the extent of the site. Financial considerations 4. The Authority has funding available to carry out this consultation. It is a requirement to complete a consultation for such documents to be given weight in the Authority’s planning decision making. Risk considerations 5. The guidance when adopted will provide an updated position regarding sites to be protected under Policy 10 ‘Local Sites of Nature Conservation or Geological Interest’. Equality considerations 6. The Public Equality Duty requires the Authority to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, promote equality of opportunity and foster good relation between different communities. This means that, in the formative stages of our policies, procedure, practice or guidelines, the Authority needs to take into account what impact its decisions will have on people who are protected under the Equality Act 2010 (people who share a protected characteristic of age, sex, race, disability, sexual Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority National Park Authority – 27 April 2016 Page 65 orientation, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, and religion or belief). -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 18 October 2018 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Caswell, E. and Roberts, B.W. (2018) 'Reassessing community cemeteries : cremation burials in Britain during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 16001150 cal BC).', Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society., 84 . pp. 329-357. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2018.9 Publisher's copyright statement: c The Prehistoric Society 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, page 1 of 29 © The Prehistoric Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust Report on Activities

Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust Report on activities carried out for Adopt-a-riverbank initiative Funded by Dulverton Trust, (Community Foundation in Wales) 23.10.15 to 1.11.16 3 December 2016 Page 1 of 15 Adopt-A-Riverbank Project 2015/16 The Adopt-A-Riverbank project aimed to get as many people as possible engaged in visiting and monitoring their local riverbank. The project was conceived as an initiative to develop and broaden the activities of Pembrokeshire Rivers Trust, building on projects that the Trust has been involved in over the last few years, such as The Cleddau Trail project, the European Fisheries Fund (EFF) project and the Coed Cymru Nature Fund river restoration project. Plans and funding bids were put together during the Summer of 2015 during the last months of the EFF project in order to create a role and bid for funding that would provide ongoing work for the EFF project staff. In July 2015 PRT applied to the Dulverton Trust (Community Fund in Wales) and also to a number of other funding streams including the Natural Resources Wales, Woodward Trust, Milford Haven Port Authority, Supermarkets 5p bag schemes and other local organisations. The aim was to fund a £40K 2 year project with ambitious targets for numbers of people reached and kilometres of riverbank adopted, and to create a sustainable framework for co-ordination and engagement of PRT’s volunteers. PRT was only successful with one of its funding applications; unfortunately no other funding was secured. The Dulverton Trust (Community Foundation in Wales) kindly awarded PRT £5,000. -

Cottages Guest Comments

Guest comments Bosherston Lily Ponds Sycamore Cottage Bosherston Kind comments from happy guests. Lily ponds wonderful. Beaches superb. Dogs shattered. Another relaxing week in Bosherston. Cottage great. Already booked for next year. Back again for a second visit. Still in awe of the location and such a lovely cottage. Hours of beautiful morning walks which cover woodland, cliff top, lily ponds, sandy beaches and all straight out of the front door. The cottage is like home from home – fabulous. Fantastic walks to Barafundle, Stackpole. Top tips - kayaking with The Prince’s Trust at Pembrokeshire Activity Centre – brilliant morning – they also do canoeing and coasteering for all ages and abilities. Carew Castle also a great place to play hide and seek! Wood burner a great bonus on cold nights. Great holiday, fabulous cottage with plenty of equipment. Well worth visiting Barafundle, St Govan’s Chapel and Pembroke Castle. Thanks for a great holiday! We are going to miss our daily stroll around the lily ponds in search of otters. We’ve had the most relaxing and enjoyable week in your beautiful cottage. The location is Book now! Contact Steve or Suzanne on: excellent and we have made the most of it. We have walked miles. We’ll be back for certain. Tel: 029 2061 4064 or 07768 416591 Email: [email protected] Web: cottages.capellcreative.co.uk Twitter: WestWalesFun Discounts for late and group bookings! Conditions apply. Contact us for more information. Sycamore Cottage Bosherston Kind comments from happy guests. This cottage is wonderfully presented and ideally situated. A thoroughly enjoyable week. -

Wales: River Wye to the Great Orme, Including Anglesey

A MACRO REVIEW OF THE COASTLINE OF ENGLAND AND WALES Volume 7. Wales. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey J Welsby and J M Motyka Report SR 206 April 1989 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX1 0 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT This report reviews the coastline of south, west and northwest Wales. In it is a description of natural and man made processes which affect the behaviour of this part of the United Kingdom. It includes a summary of the coastal defences, areas of significant change and a number of aspects of beach development. There is also a brief chapter on winds, waves and tidal action, with extensive references being given in the Bibliography. This is the seventh report of a series being carried out for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. For further information please contact Mr J M Motyka of the Coastal Processes Section, Maritime Engineering Department, Hydraulics Research Limited. Welsby J and Motyka J M. A Macro review of the coastline of England and Wales. Volume 7. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey. Hydraulics Research Ltd, Report SR 206, April 1989. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COASTAL GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.1 Geological background 3.2 Coastal processes 4 WINDS, WAVES AND TIDAL CURRENTS 4.1 Wind and wave climate 4.2 Tides and tidal currents 5 REVIEW OF THE COASTAL DEFENCES 5.1 The South coast 5.1.1 The Wye to Lavernock Point 5.1.2 Lavernock Point to Porthcawl 5.1.3 Swansea Bay 5.1.4 Mumbles Head to Worms Head 5.1.5 Carmarthen Bay 5.1.6 St Govan's Head to Milford Haven 5.2 The West coast 5.2.1 Milford Haven to Skomer Island 5.2.2 St Bride's Bay 5.2.3 St David's Head to Aberdyfi 5.2.4 Aberdyfi to Aberdaron 5.2.5 Aberdaron to Menai Bridge 5.3 The Isle of Anglesey and Conwy Bay 5.3.1 The Menai Bridge to Carmel Head 5.3.2 Carmel Head to Puffin Island 5.3.3 Conwy Bay 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY FIGURES 1. -

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

Parker Pearson, M 2013 Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International, No. 16 (2012-2013): 72-83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ai.1601 ARTICLE Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present Mike Parker Pearson* Over the years archaeologists connected with the Institute of Archaeology and UCL have made substantial contributions to the study of Stonehenge, the most enigmatic of all the prehistoric stone circles in Britain. Two of the early researchers were Petrie and Childe. More recently, colleagues in UCL’s Anthropology department – Barbara Bender and Chris Tilley – have also studied and written about the monument in its landscape. Mike Parker Pearson, who joined the Institute in 2012, has been leading a 10-year-long research programme on Stonehenge and, in this paper, he outlines the history and cur- rent state of research. Petrie and Childe on Stonehenge William Flinders Petrie (Fig. 1) worked on Stonehenge between 1874 and 1880, publishing the first accurate plan of the famous stones as a young man yet to start his career in Egypt. His numbering system of the monument’s many sarsens and blue- stones is still used to this day, and his slim book, Stonehenge: Plans, Descriptions, and Theories, sets out theories and observations that were innovative and insightful. Denied the opportunity of excavating Stonehenge, Petrie had relatively little to go on in terms of excavated evidence – the previous dig- gings had yielded few prehistoric finds other than antler picks – but he suggested that four theories could be considered indi- vidually or in combination for explaining Stonehenge’s purpose: sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental. -

Marine Character Areas MCA 19 WEST PEMBROKESHIRE

Marine Character Areas MCA 19 WEST PEMBROKESHIRE ISLANDS, BARS & INSHORE WATERS Location and boundaries This Marine Character Area comprises the inshore waters off the west Pembrokeshire coast, encompassing the offshore islands of the Bishops and Clerks, Grassholm and The Smalls. The boundary between this MCA and MCA 17 (Outer Cardigan Bay) is consistent with a change from low energy sub-littoral sediment in the eastern part of this MCA to moderate/high energy sub-littoral sediment influencing MCA 17. The southern boundary is formed along a distinct break between marine sediments. The northern offshore boundary follows the limits of the Wales Inshore Marine Plan Area. The MCA encompasses all of the following Pembrokeshire local SCAs: 12: Strumble Head Deep Water; 14: Western Sand and Gravel Bars; 19: Bishops and Clerks; 28: West Open Sea; and 27: Grassholm and The Smalls. It also includes the western part of SCA 8: North Open Sea MCA 19 West Pembrokeshire Islands, Bars & Inshore Waters - Page 1 of 7 Key Characteristics Key Characteristics Varied offshore MCA with a large area of sea, ranging from 30-100m in depth on a gravelly sand seabed. A striking east-west volcanic bedrock ridges form a series of islands (Smalls, Grassholm and Bishops and Clerks), rock islets and reefs along submarine ridges, interspersed with moderately deep channels off the west coast. Two elongated offshore bars of gravelly sand lie on the seabed parallel to the coastline, shaped in line with tidal stream. Bais Bank (parallel with St David’s Head) includes shallows of less than 10m depth and dangerous shoals/overfalls. -

Archaeology Wales

Archaeology Wales Goldcroft Common Caerleon, Newport Archaeological Watching Brief By Jennifer Muller Report No. 1684 Archaeology Wales Limited The Reading Room, Town Hall, Llanidloes, SY18 6BN Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 Email: [email protected] Web: arch-wales.co.uk Archaeology Wales Goldcroft Common, Caerleon, Newport Archaeological Watching Brief Prepared For: Western Power Distribution Edited by: Philip Poucher Authorised by: Mark Houliston Signed: Signed: Position: Philip Poucher Position: Managing Director Date 29/05/18: Date: 04/06/18 By Jennifer Muller Report No. 1684 May 2018 Archaeology Wales Limited The Reading Room, Town Hall, Llanidloes, SY18 6BN Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 Email: [email protected] Web: arch-wales.co.uk Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Methodology 3 3. Watching Brief Results 4 4. Finds 5 5. Conclusion 5 6. Bibliography 5 List of Figures Figure 1 Location map of the site Figure 2 Location map of the excavation Figure 3 Plan of excavated area List of Plates Photo 1 Driveway prior to excavation Photo 2 Trench section at northwest end Photo 3 Trench in plan at northwest end Photo 4 Trench section near northwest end Photo 5 Trench section in centre of driveway Photo 6 Trench section at southeast end of driveway Photo 7 General shot of trench within driveway Photo 8 General shot of trench in road Photo 9 Southeast facing trench section in road Photo 10 Northwest facing trench section in road Appendices Appendix I Context Register Appendix II Written Scheme of Investigation Appendix III Archive Cover Sheet Copyright Notice: Archaeology Wales Ltd. -

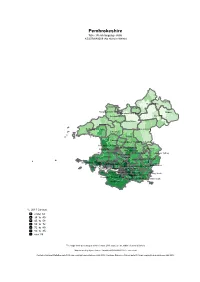

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St. -

Existing Electoral Arrangements

COUNTY OF PEMBROKESHIRE EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Page 1 2012 No. OF ELECTORS PER No. NAME DESCRIPTION ELECTORATE 2012 COUNCILLORS COUNCILLOR 1 Amroth The Community of Amroth 1 974 974 2 Burton The Communities of Burton and Rosemarket 1 1,473 1,473 3 Camrose The Communities of Camrose and Nolton and Roch 1 2,054 2,054 4 Carew The Community of Carew 1 1,210 1,210 5 Cilgerran The Communities of Cilgerran and Manordeifi 1 1,544 1,544 6 Clydau The Communities of Boncath and Clydau 1 1,166 1,166 7 Crymych The Communities of Crymych and Eglwyswrw 1 1,994 1,994 8 Dinas Cross The Communities of Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross and Puncheston 1 1,307 1,307 9 East Williamston The Communities of East Williamston and Jeffreyston 1 1,936 1,936 10 Fishguard North East The Fishguard North East ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,473 1,473 11 Fishguard North West The Fishguard North West ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,208 1,208 12 Goodwick The Goodwick ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,526 1,526 13 Haverfordwest: Castle The Castle ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,651 1,651 14 Haverfordwest: Garth The Garth ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,798 1,798 15 Haverfordwest: Portfield The Portfield ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,805 1,805 16 Haverfordwest: Prendergast The Prendergast ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,530 1,530 17 Haverfordwest: Priory The Priory ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,888 1,888 18 Hundleton The Communities of Angle.