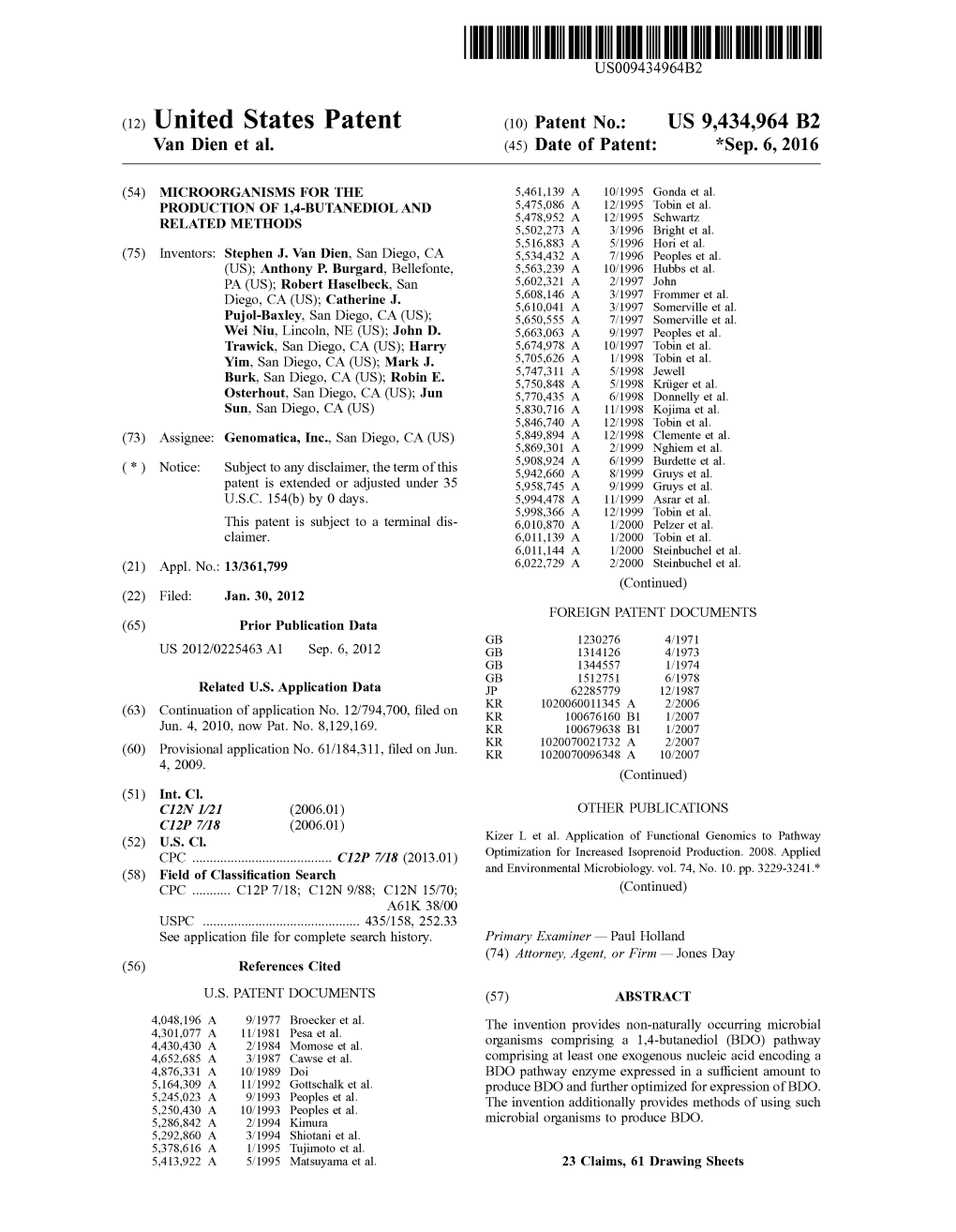

CPC..W. Crop 718 (2013.01) Optimization for Neas Opened Duction 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bacterial Aromatic Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Critical for The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A bacterial aromatic aldehyde dehydrogenase critical for the efficient catabolism of Received: 21 October 2016 Accepted: 07 February 2017 syringaldehyde Published: 15 March 2017 Naofumi Kamimura1, Takayuki Goto1, Kenji Takahashi1, Daisuke Kasai1, Yuichiro Otsuka2, Masaya Nakamura2, Yoshihiro Katayama3, Masao Fukuda1 & Eiji Masai1 Vanillin and syringaldehyde obtained from lignin are essential intermediates for the production of basic chemicals using microbial cell factories. However, in contrast to vanillin, the microbial conversion of syringaldehyde is poorly understood. Here, we identified an aromatic aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene responsible for syringaldehyde catabolism from 20 putative ALDH genes of Sphingobium sp. strain SYK-6. All these genes were expressed in Escherichia coli, and nine gene products, including previously characterized BzaA, BzaB, and vanillin dehydrogenase (LigV), exhibited oxidation activities for syringaldehyde to produce syringate. Among these genes, SLG_28320 (desV) and ligV were most highly and constitutively transcribed in the SYK-6 cells. Disruption of desV in SYK-6 resulted in a significant reduction in growth on syringaldehyde and in syringaldehyde oxidation activity. Furthermore, a desV ligV double mutant almost completely lost its ability to grow on syringaldehyde. Purified DesV showed −1 −1 −1 −1 similar kcat/Km values for syringaldehyde (2100 s ·mM ) and vanillin (1700 s ·mM ), whereas LigV substantially preferred vanillin (8800 s−1·mM−1) over syringaldehyde (1.4 s−1·mM−1). These results clearly demonstrate that desV plays a major role in syringaldehyde catabolism. Phylogenetic analyses showed that DesV-like ALDHs formed a distinct phylogenetic cluster separated from the vanillin dehydrogenase cluster. Lignin is the second most abundant bio-resource on earth after cellulose, and its decomposition is essential for the carbon cycle. -

Oxidative Pathways of Deoxyribose and Deoxyribonate Catabolism

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/205583; this version posted November 12, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Oxidative pathways of deoxyribose and deoxyribonate catabolism 1* 1 2 1 Morgan N. Price, Jayashree Ray, Anthony T. Iavarone, Hans K. Carlson, Elizabeth M. 3 3 1,4,* 1,5,* Ryan, Rex R. Malmstrom, Adam P. Arkin, and Adam M. Deutschbauer 1 Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley CA, USA 2 QB3/Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of California, Berkeley CA, USA 3 DOE Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek CA, USA 4 Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Berkeley CA, USA 5 Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley CA, USA * [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Using genome-wide mutant fitness assays in diverse bacteria, we identified novel oxidative pathways for the catabolism of 2-deoxy-D-ribose and 2-deoxy-D-ribonate. We propose that deoxyribose is oxidized to deoxyribonate, oxidized to ketodeoxyribonate, and cleaved to acetyl-CoA and glyceryl-CoA. We have genetic evidence for this pathway in three genera of bacteria, and we confirmed the oxidation of deoxyribose to ketodeoxyribonate in vitro. In Pseudomonas simiae, the expression of enzymes in the pathway is induced by deoxyribose or deoxyribonate, while in Paraburkholderia bryophila and in Burkholderia phytofirmans, the pathway proceeds in parallel with the known deoxyribose 5-phosphate aldolase pathway. -

Characterization of Cd36 03230P, a Putative Vanillin Dehydrogenase from Candida Dubliniensis† Cite This: RSC Adv.,2016,6, 99774 Suprama Datta,Ab Uday S

RSC Advances View Article Online COMMUNICATION View Journal | View Issue Characterization of Cd36_03230p, a putative vanillin dehydrogenase from Candida dubliniensis† Cite this: RSC Adv.,2016,6, 99774 Suprama Datta,ab Uday S. Annapureb and David J. Timson*ac Received 5th September 2016 Accepted 10th October 2016 DOI: 10.1039/c6ra22209a www.rsc.org/advances A coding sequence (CD36-03230) from the yeast Candida dubliniensis derived phenylpropanoids (such as vanillin, vanillate, caffeate, p- had been previously annotated as a vanillin dehydrogenase (VDH). The coumarate, cinnamate and benzaldehyde). These aromatic alde- corresponding protein (CD36-03230p) was recombinantly expressed hydes, especially vanillin, are abundant as avour and aromas in in Escherichia coli and analysed. The protein is most likely a tetramer in food and cosmetic industries. It is important to elucidate the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. solution as judged by crosslinking and gel filtration experiments. structural and functional characteristics of these enzymes given CD36-03230p is an active aldehyde dehydrogenase favouring cyclic their potential role in food chemistry and biotechnology. This and aromatic substrates. Positive cooperativity and substrate inhibition group of enzymes has been characterized in a number of eubac- were observed with some substrates. The redox cofactor NADP+ and terial species, including Pseudomonas uorescens,6 Pseudomonas substrates affected the thermal stability of the protein. Interestingly, putida KT2440,13 Corynebacterium -

Genomic Analysis of the Aromatic Catabolic Pathways from Silicibacter Pomeroyi DSS-3

Annals of Microbiology, 59 (4) 789-800 (2009) Genomic analysis of the aromatic catabolic pathways from Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 Dazhong YAN1, Jianxiong KANG2, Dong-Qi LIU2* 1School of Biology and Pharmaceutical Engineering, Wuhan Polytechnic University, Wuhan, 430023; 2Center for Microbiology Engineering, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, No. 1037 Luoyue Road, Wuhan 430074, P.R. China Received 16 June 2009 / Accepted 7 October 2009 Abstract - Genomic analysis of the catabolic potentialities of Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 against a wide range of natural aromatic compounds and sequence comparisons with the entire genome of this microorganism predicted the existence of at least seven main pathways for the conversion of the aromatic compounds to the intermediates which enter into TCA cycle, that is, the catechol (cat I and cat II genes) and protocatechuate (pca genes) branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway, the phenylacetate pathway (paa genes), the gentisate pathway (gtd genes), the homogentisate pathway (hmg/hppD genes), as well as the homoprotocatechuate pathway (hpc genes). Furthermore, the genes encoding those enzymes involved in the peripheral pathways leading to the β-ketoadipate central pathway were also mapped, i.e., 4-hydroxybenzoate (pob), benzoate (ben), quinate (qui), phenylpropenoid compounds (fcs, ech, vdh, cal, van, acd and act), tyrosine (hpp) and n-phenylalkanoic acids (fad). Evidences showed that S. pomeroyi DSS-3 have versatile abili- ties to the catabolism of aromatic compounds either in anaerobic or in aerobic pathway, suggesting such a strain might be a model of heuristic value for the study of the genomic organization, the evolution of genes, as well as the catalytic or transcriptional mechanisms of enzymes for aromatic degradation in marine bacteria. -

Characterization of Cd36 03230P, a Putative Vanillin Dehydrogenase from Candida Dubliniensis† Cite This: RSC Adv.,2016,6, 99774 Suprama Datta,Ab Uday S

RSC Advances View Article Online COMMUNICATION View Journal | View Issue Characterization of Cd36_03230p, a putative vanillin dehydrogenase from Candida dubliniensis† Cite this: RSC Adv.,2016,6, 99774 Suprama Datta,ab Uday S. Annapureb and David J. Timson*ac Received 5th September 2016 Accepted 10th October 2016 DOI: 10.1039/c6ra22209a www.rsc.org/advances A coding sequence (CD36-03230) from the yeast Candida dubliniensis derived phenylpropanoids (such as vanillin, vanillate, caffeate, p- had been previously annotated as a vanillin dehydrogenase (VDH). The coumarate, cinnamate and benzaldehyde). These aromatic alde- corresponding protein (CD36-03230p) was recombinantly expressed hydes, especially vanillin, are abundant as avour and aromas in in Escherichia coli and analysed. The protein is most likely a tetramer in food and cosmetic industries. It is important to elucidate the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. solution as judged by crosslinking and gel filtration experiments. structural and functional characteristics of these enzymes given CD36-03230p is an active aldehyde dehydrogenase favouring cyclic their potential role in food chemistry and biotechnology. This and aromatic substrates. Positive cooperativity and substrate inhibition group of enzymes has been characterized in a number of eubac- were observed with some substrates. The redox cofactor NADP+ and terial species, including Pseudomonas uorescens,6 Pseudomonas substrates affected the thermal stability of the protein. Interestingly, putida KT2440,13 Corynebacterium -

Generation of Flavors and Fragrances Through Biotransformation and De Novo Synthesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade do Minho: RepositoriUM Food and Bioprocess Technology (2018) 11:2217–2228 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-018-2180-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Generation of Flavors and Fragrances Through Biotransformation and De Novo Synthesis Adelaide Braga1 & Carlos Guerreiro1 & Isabel Belo1 Received: 8 May 2018 /Accepted: 10 September 2018 /Published online: 19 September 2018 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Flavors and fragrances are the result of the presence of volatile and non-volatile compounds, appreciated mostly by the sense of smell once they usually have pleasant odors. They are used in perfumes and perfumed products, as well as for the flavoring of foods and beverages. In fact the ability of the microorganisms to produce flavors and fragrances has been described for a long time, but the relationship between the flavor formation and the microbial growth was only recently established. After that, efforts have been put in the analysis and optimization of food fermentations that led to the investigation of microorganisms and their capacity to produce flavors and fragrances, either by de novo synthesis or biotransformation. In this review, we aim to resume the recent achievements in the production of the most relevant flavors by bioconversion/biotransformation or de novo synthesis, its market value, prominent strains used, and their production rates/maximum concentrations. Keywords Bioconversion . Biotransformation . De novo synthesis . Flavors . Fragrances Introduction fact, chemical synthesis still represents the cheaper technol- ogy for their production; however, it may require harsh Flavors and fragrances have a wide application in the food, conditions (toxic catalysts, high pressure and temperature, feed, cosmetic, chemical, and pharmaceutical sectors among others) and usually lack adequate regio- and (Vandamme 2003). -

Efficient Synthesis of 4-Vinyl Guaiacol Via Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid By

Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2016; 43(1) : 158-168 http://epg.science.cmu.ac.th/ejournal/ Contributed Paper Efficient Synthesis of 4-Vinyl Guaiacol via Bioconversion of Ferulic Acid by Volvariella volvacea Keerati Tanruean [a,b] and Nuansri Rakariyatham*[b,c] [a] Division of Biotechnology, Graduate School, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand. [b] Department of Chemistry and Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand. [c] Faculty of Health Science, Nation University, Lampang 52000, Thailand. *Author for correspondence; e-mail: [email protected] Received: 8 March 2014 Accepted: 7 July 2014 ABSTRACT Ferulic acid is a phenolic compound that is extremely abundant in the cell walls of plants. It has been of interest for use as a starting material in the bioconversion process of subsequent highly valuable compounds. In this study, Volvariella volvacea was investigated for its ability to convert ferulic acid to various products of degradation (4-vinyl guaiacol, vanillic acid and vanillyl alcohol) by HPLC and LC-DAD-ESIMS. The results showed that the mycelium of V. volvacea had potential to produce high amounts of 4-vinyl guaiacol (88.2 mg/L), vanillic acid (59.1 mg/L) and vanillyl alcohol (39.7 mg/L) at 42, 42 and 96 hours of growth on ferulic acid medium, respectively. Moreover, the effects of various sulfhydryl compounds and their derivatives of sulfur containing amino acids: cysteine, cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate, dithiothreitol, glutathione and methionine treatment on ferulic acid bioconversion were also investigated. Most all of the sulfhydryl compounds, except dithiothreitol, could enhance 4-vinyl guaiacol production; especially cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate which displayed a 47.9% increase in 4-vinyl guaiacol production (136.7 mg/L) when compared with the control. -

Genomic Analysis of Burkholderia Sp. ISTR5 for Biofunneling of Lignin‑Derived Compounds Raj Morya, Madan Kumar, Shashi Shekhar Singh and Indu Shekhar Thakur*

Morya et al. Biotechnol Biofuels (2019) 12:277 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1606-5 Biotechnology for Biofuels RESEARCH Open Access Genomic analysis of Burkholderia sp. ISTR5 for biofunneling of lignin-derived compounds Raj Morya, Madan Kumar, Shashi Shekhar Singh and Indu Shekhar Thakur* Abstract Background: Lignin is the second most abundant natural polymer on earth. Industries using lignocellulosic bio- mass as feedstock generate a considerable amount of lignin as a byproduct with minimal usage. For a sustainable biorefnery, the lignin must be utilized in improved ways. Lignin is recalcitrant to degradation due to the complex and heterogeneous structure. The depolymerization of lignin and its conversion into specifc product stream are the major challenges associated with lignin valorization. The blend of oligomeric, dimeric and monomeric lignin-derived compounds (LDCs) generated during depolymerization can be utilized by microbes for production of bioproducts. Results: In the present study, a novel bacterium Burkholderia sp. strain ISTR5 (R5), a proteobacteria belonging to class betaproteobacteria, order Burkholderiales and family Burkholderiaceae, was isolated and characterized for the degrada- tion of LDCs. R5 strain was cultured on 12 LDCs in mineral salt medium (MSM) supplemented with individual com- pounds such as syringic acid, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, vanillin, vanillic acid, guaiacol, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, gallic acid, benzoic acid, syringaldehyde, veratryl alcohol and catechol. R5 was able to grow and utilize all the selected LDCs. The degradation of selected LDCs was monitored by bacterial growth, total organic carbon (TOC) removal and UV–Vis absorption spectra in scan mode. TOC reduction shown in the sample contains syringic acid 80.7%, ferulic acid 84.1%, p-coumaric acid 85.9% and benzoic acid 83.2%. -

Index of Recommended Enzyme Names

Index of Recommended Enzyme Names EC-No. Recommended Name Page 1.2.1.10 acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acetylating) 115 1.2.1.38 N-acetyl-y-glutamyl-phosphate reductase 289 1.2.1.3 aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) 32 1.2.1.4 aldehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) 63 1.2.99.3 aldehyde dehydrogenase (pyrroloquinoline-quinone) 578 1.2.1.5 aldehyde dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+] 72 1.2.3.1 aldehyde oxidase 425 1.2.1.31 L-aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 262 1.2.1.19 aminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase 195 1.2.1.32 aminomuconate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 271 1.2.1.29 aryl-aldehyde dehydrogenase 255 1.2.1.30 aryl-aldehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) 257 1.2.3.9 aryl-aldehyde oxidase 471 1.2.1.11 aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 125 1.2.1.6 benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (deleted) 88 1.2.1.28 benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) 246 1.2.1.7 benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (NADP+) 89 1.2.1.8 betaine-aldehyde dehydrogenase 94 1.2.1.57 butanal dehydrogenase 372 1.2.99.2 carbon-monoxide dehydrogenase 564 1.2.3.10 carbon-monoxide oxidase 475 1.2.2.4 carbon-monoxide oxygenase (cytochrome b-561) 422 1.2.1.45 4-carboxy-2-hydroxymuconate-6-semialdehyde dehydrogenase .... 323 1.2.99.6 carboxylate reductase 598 1.2.1.60 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase . 383 1.2.1.44 cinnamoyl-CoA reductase 316 1.2.1.68 coniferyl-aldehyde dehydrogenase 405 1.2.1.33 (R)-dehydropantoate dehydrogenase 278 1.2.1.26 2,5-dioxovalerate dehydrogenase 239 1.2.1.69 fluoroacetaldehyde dehydrogenase 408 1.2.1.46 formaldehyde dehydrogenase 328 1.2.1.1 formaldehyde dehydrogenase (glutathione) -

Molecular Cloning and Characterization of Vanillin Dehydrogenase from Streptomyces Sp

Nishimura et al. BMC Microbiology (2018) 18:154 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-018-1309-2 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Molecular cloning and characterization of vanillin dehydrogenase from Streptomyces sp. NL15-2K Motohiro Nishimura* , Susumu Kawakami and Hideaki Otsuka Abstract Background: Streptomyces sp. NL15-2K, previously isolated from the forest soil, features an extensive catabolic network for lignin-derived aromatic compounds, including pathways transforming ferulic acid to vanillin, vanillic acid, and protocatechuic acid. To successfully use Streptomyces sp. NL15-2K as a biocatalyst for vanillin production, it is necessary to characterize the vanillin dehydrogenase (VDH) that degrades the produced vanillin to vanillic acid, as well as the gene encoding this enzyme. Here, we cloned the VDH-encoding gene (vdh) from strain NL15-2K and comprehensively characterized its gene product. Results: The vdh open reading frame contains 1488 bp and encodes a 496-amino-acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 51,705 Da. Whereas the apparent native molecular mass of recombinant VDH was estimated to be 214 kDa by gel filtration analysis, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed a subunit molecular mass of ca. 56 kDa, indicating that VDH is a homotetramer. The recombinant enzyme showed optimal activity at 45 °C and pH 9.5. The VDH substrate specificity followed this order: vanillin (100%) > protocatechualdehyde (91%) > benzaldehyde (79%) > p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (56%) > isovanillin (49%) ≈ salicylaldehyde (48%) > anisaldehyde (15%) ≈ veratraldehyde (12%). Although peptide mass fingerprinting and BLAST searches indicated that this enzyme is a salicylaldehyde dehydrogenase (SALDH), the determined kinetic parameters clearly demonstrated that the enzyme is a vanillin dehydrogenase. -

Identifying and Creating Pathways to Improve Biological Lignin Valorization T ⁎ Zhi-Hua Liua,B,1, Rosemary K

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 105 (2019) 349–362 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rser Identifying and creating pathways to improve biological lignin valorization T ⁎ Zhi-Hua Liua,b,1, Rosemary K. Lec,1, Matyas Kosad, Bin Yange, Joshua Yuana,b, , ⁎⁎ Arthur J. Ragauskasc,f,g, a Synthetic and Systems Biology Innovation Hub (SSBiH), Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, United States b Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, United States c Department of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering, University of Tennessee Knoxville, Knoxville, TN 37996, United States d Fortress Advanced Bioproducts Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1W5 e Bioproducts, Sciences, and Engineering Laboratory, Department of Biological Systems Engineering, Washington State University, Richland, WA 99354, United States f Joint Institute for Biological Sciences, Biosciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831, United States g Center for Renewable Carbon, Department of Forestry, Wildlife, and Fisheries, University Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Biological lignin valorization to fuels and value-added chemicals enables sustainable and economic biorefineries. Biological lignin valorization While significant progress has been made, several major challenges arose due to high recalcitrance and het- Ligninolytic microorganism erogeneity of lignin, which needs to be addressed to improve lignin processing. This work provides an overview Bioprospecting of biological lignin conversion and its regulation from a metabolic engineering and systems biology viewpoint. Metabolic engineering Biological lignin valorization includes three stages: lignin depolymerization, aromatics degradation, and target Systems biology product biosynthesis. -

Does DNA Methylation Level Play a Role?

Epigenetic regulation of Verticillium dahliae virulence: does DNA methylation level play a role? Jorge A. Ramírez-Tejero1, Carmen Gómez-Lama Cabanás2, Antonio Valverde- Corredor2, Jesús Mercado-Blanco2 and Francisco Luque1* 1Center for Advanced Studies in Olive Grove and Olive Oils, Department of Experimental Biology, Univ. Jaén, 23071-Jaén, Spain 2Department of Crop Protection, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture, Agencia Estatal Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Campus ‘Alameda del Obispo’, Avenida Menéndez Pidal s/n, Apartado 14004 Córdoba, Spain Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]. *Corresponding author F. Luque, [email protected]. ORCiD ID: 0000-0003-1354-3533 Table S1 937‐HP_NODE_NU GENE NAME GENE LENGDIFF % 937‐138_NODE_NUMGENE LE DIFF % 937‐150_NODE_NGENE LE DIFF % 937‐403_NODE_NGENE LENDIFF % 100g0000040.1 Unknown protein 2903 55 1,894591802 100g0000040.1 2903 ‐197,5 ‐6,803306924 100g0000040.1 2903 41,5 1,429555632 100g0000040.1 2903 ‐68 ‐2,342404409 100g0000050.1 Unknown protein 2732 66 2,415812592 100g0000050.1 2732 ‐133 ‐4,868228404 100g0000050.1 2732 69,5 2,543923865 100g0000050.1 2732 ‐44,5 ‐1,628843338 100g0000060.1 Unknown protein 1986 27,5 1,38469285 100g0000060.1 1986 ‐108,5 ‐5,463242699 100g0000060.1 1986 36 1,812688822 100g0000060.1 1986 ‐27 ‐1,359516616 100g0000190.1 Unknown protein 569 60 10,54481547 100g0000190.1 569 ‐26 ‐4,569420035 100g0000190.1 569 24 4,217926186 100g0000190.1 569 ‐12,5 ‐2,196836555 1013g0000010.1