Michael Hathaway Simon Fraser University Please Do Not Cite Without Author’S Permission Comments Welcome: [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamonegi Menu

S T A R T E R shishito: shishito pepper, spicy mentaiko "cod roe" aioli …..9 tsukemono: assorted house made vegetable pickles ….. 9 addictive korinki: korinki squash, bamboo, blackened chili oil, roasted peanuts .....9 heirloom tomato kimchi: local heirloom tomato kimchi, shiso, sesame, chili oil .....12 foie gras "tofu": foie gras, sake poached shrimp, wasabi, 2 year aged zaru sauce .....12 albacore zuke tataki: sashimi style albacore tuna, steamed eggplant, sapporo pepper yakibidashi, yuzu miso vin .....13 yakitori duck tsukune: house made duck meatballs, eggplant, sous vide egg, shishito …..14* T E M P U R A zucchini coin: local zucchini tempura, sweet and salty umami powder ..... 7 satsuma yam tempura: sweet dashi, habanero maple syrup, blue cheese, walnuts ….. 11 broccolini tempura: asiago cheese, miso anchovy aioli ….. 12 eggplant tempura: lobster mushroom, dashi broth, purple daikon, bonito, mitsuba ….. 13 anago tempura: sea eel, s&b curry salt, lemon ….. 14 shrimp tempura: [2pc], daikon oroshi, tempura broth ….. 9 nagoya wings: [6pc], fried chicken wings, secret yakitori sauce, sesame ..... 14 B U K K A K E S O B A nattou bukkake: housemade fermented soybeans, shiso, nori, micro green, sous vide egg, karashi mustard ..... 19 shrimpcado bukkake: shrimp tempura, avocado, cucumber, daikon oroshi, wasabi ..... 20 tomato kimchi bukkake: local organic heirloom tomato kimchi, shiso, garlic, scallion, onion, sesame ..... 21 hiya-jiru bukkake: grilled saba "mackerel" miso paste, myoga ginger, tofu, sesame, shiso ..... 20 S E I R O S O B A ten zaru: soba with side of chilled broth, seasonal vegetable tempura, wasabi, scallion ….. 22 karee : japanese vegetable curry, leek, mozzarella …. -

Appetizers Black Sesame Tofu, Soy Milk Skin and Salmon Roe With

RAN Appetizers Black Sesame Tofu, Soy Milk Skin and Salmon Roe with Dashi Jelly Potherb Mustard, Boiled and Seasoned White Maitake Mushroom Dried Squid Mushroom with Grated Radish and Ponzu Soup Arrowroot Starch Soup Crab Dumpling, White Cloud Ear Mushroom, Green Beans Carrot and Ginger Sashimi A Selection of Seasonal Sashimi (Change 3 kinds of sashimi to 5 kinds, additional charge of 1500yen) Broiled Dish Barracuda Broiled and Boiled in Dashi, Sudachi Citrus Vinegared Vegetables and Grilled Eggplant Organic Beef Fillet with Vegetables (Bell Pepper and Broccoli and so on) Japanese Sauce and Whole-grain Mustard Fried Dish Assorted Tempura Braised Dish Lily Bulb Dumpling, Shimeji Mushroom, Green with Starchy Sauce Rice Dish Nigiri Sushi and Rolled Sushi with Miso Soup Dessert Assorted Seasonal Dessert with Wine Jelly ¥11,000 The menu may change without prior notice. We use domestic rice. Please notify us in advance if you have any allergy to specific food items such as gluten or lactose. 13% service charge and consumption tax will be add to your bill. MIYABI Appetizers Scallop Cooked with Sake, Welsh Onion, White Maitake Mushroom Radish and Chervil Mustard Vinegar Miso Dressing, Bonito Vinegar Sauce Steamed Dish Mini Egg Custard: Hamo Japanese Conger, Soy Milk Skin Lily Bulb and Starchy Dashi Sauce Sashimi A Selection of Seasonal Sashimi (Change 3 kinds of sashimi to 5 kinds, additional charge of 1500yen) Broiled Dish Salmon, Mushrooms, Mitsuba Green and Ginkgo Nuts Roasted Chestnuts, Vinegared Vegetables Boiled and Seasoned Vegetable with Bonito Flakes Temari Sushi Balls Main Dish Broiled Sea Bream, Burdock Root, Taro, Green Beans, Ginger or Assorted Tempura with Grated Radish, Ginger and Andes Salt Hot Dish Lotus Root Dumpling Rice Dish Rice Cooked with Chestnuts or Steamed Rice Miso Soup with Japanese Pickles Dessert Assorted Seasonal Fruits with Wine Jelly ¥8,000 The menu may change without prior notice. -

Snow Castle Autumn Menu

Snow Castle Autumn Menu Appetizer Crab and Mushroom with Grated Daikon Radish Grilled Duck with Saikyo Miso AKKESHI Oyster Tempura Steamed Dish Steamed Consommé Soup Egg Custard with Matsutake Mushroom Cold Dish Local Assorted Sashimi Hot Dish MAKKARI Lily Bulb Dumpling Mushroom Sauce Grilled Dish Salt Grilled Sea Urchin and Abalone Main Dish Grilled Hokkaido Wagyu Beef Rice Pot Steamed Rice with Salmon and Matsutake Mushrooms Or Assorted Sushi Miso soup Dessert Apple Ice Cream Baked Sweet Potato Pudding JPY 10 ,000 per person (10% service charge and 10% consumption tax are not included) Snow Castle Autumn Menu Appetizer Mushroom and Grated Daikon Radish with Salmon Roe Grilled Duck with Saikyo Miso Steamed Dish Steamed Consommé Soup Egg Custard with Matsutake Mushroom Cold Dish Assorted Sashimi Hot Dish Small Hot Pot of Eel with Simmered Eggs Deep Fried Dish AKKESHI Oyster Tempura Main Dish Grilled Hokkaido Wagyu Beef Rice Pot Steamed Rice with Hokkaido SAMMA Fish(Pacific Saury) Miso soup Dessert Apple Ice Cream JPY 8,000 per person (10% service charge and 10% consumption tax are not included) Snow Castle Autumn Menu Appetizer Crab with RAKUYO Mushrooms and Persimmon Grated Daikon Radish Hot Dish Small Hot Pot of Eel and Eggplant with Simmered Eggs Grilled Dish Grilled RUSUTSU Pork Marinated in Saikyo Miso SUSHI Assorted Sushi Miso soup Dessert Apple Ice Cream JPY 6,000 per person (10% service charge and 10% consumption tax are not included). -

Matsis and Wannabees: a Primer on Pine Mushrooms

Britt A. Bunyard [email protected] Figure 1. Three matsutakes? Look again. These three Tricholoma species were collected by John Sparks in New Mexico and growing within 100 feet of one another. From left to right, Tricholoma focale, T. caligatum, and T. magnivelare. Identifications were confirmed with DNA analysis by Dr. Clark Ovrebo. Photo courtesy of J. Sparks. described (Arora, 1979). And what of rumors that we have the “true” matsutake of Asia in parts of North America? Whether you call it pine mushroom or matsutake (or simply the more affectionate nickname “matsi”), there can be no question that this mushroom is one of the most highly prized in the world. It can be an acquired taste to Westerners (I personally love them!); among Japanese this mushroom is king, with prices for top specimens fetching kings’ ransoms. Annually, Japanese matsutake mavens will spend US$50-100 for a single top quality specimen and prices many times this are regularly reported. Because the demand far f you reside in Canada you likely call exceeds the supply in Japan (97% of them pine mushrooms; in the USA, matsutake mushrooms consumed in most refer to them by their Japanese Japan, annually, are imported, according Iname, matsutake. Is it Tricholoma to the Japanese Tariff Association magnivelare or T. matsutake? And what [Ota et al., 2012]), commercial about those other matsi lookalikes? pickers descend upon North America Some smell remarkably similar to the (especially in the Pacific Northwest) Figure 2. Catathelasma imperiale “provocative compromise between every autumn with hopes of striking red hots and dirty socks” that Arora from Vancouver Island, British gold. -

Le Bernardin

Chef’s Tasting Menu* —Per Table Only— Tuna Layers of Thinly Pounded Yellowfin Tuna; Foie Gras, Toasted Baguette, Chives Extra Virgin Olive Oil Albariño, “Lagar de Pintos,” Rías Baixas, Spain 2017 Crab Warm Peekytoe Crab; Yuzu Rice Green Tea-Nori Consommé Meursault, Domaine Ballot-Millot, Burgundy, France 2018 Le Bernardin Dover Sole Sautéed Dover Sole; Almonds, Chanterelles 155 W 51st St, New York, NY 10019 Soy-Lime Emulsion Krug, “Grand Cuvée 168ème Edition”, Reims, France NV Salmon Barely Cooked Faroe Islands Salmon Black Truffle “Pot-au-Feu” Marsannay, Sylvain Pataille, Burgundy, France 2018 Apple Brown Butter Mousse, Apple Confit Armagnac Sabayon Zweigelt, Beerenauslese, Alois Kracher, Neusiedlersee, Austria 2017 “The Egg” Milk Chocolate Pot de Crème, Caramel Foam, Maple Syrup, Grain of Salt $210 per person Chef: Eric Ripert $360 with wine pairing per person Le Bernardin Four Course Prix Fixe* Almost Raw Barely Touched Lightly Cooked Caviar Sea Trout Dover Sole Royal Osetra Caviar Warm Sea Trout “Sashimi”; Osetra Caviar Sautéed Dover Sole; Almonds, Chanterelles ($145 Supplement per ounce) Light Marinière Sauce Soy-Lime Emulsion Golden Imperial Caviar ($50 Supplement) ($25 Supplement) ($155 Supplement per ounce) Crab Salmon Oysters Barely Cooked Faroe Islands Salmon Single Variety or Assortment of Oysters (Six Pieces) Warm Peekytoe Crab; Yuzu Rice Green Tea-Nori Consommé Black Truffle “Pot-au-Feu” Upon Request Tuna Filet Mignon Layers of Thinly Pounded Yellowfin Tuna Red Snapper Pan Roasted Filet Mignon; Creamy Polenta, Wild Mushrooms -

Autumn Omakase a TASTING MENU from TATSU NISHINO of NISHINO

autumn omakase A TASTING MENU FROM TATSU NISHINO OF NISHINO By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman Photographs by Peyman Oreizy First published in 2005 by tastingmenu.publishing Seattle, WA www.tastingmenu.com/publishing/ Copyright © 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publisher. Photographs © tastingmenu and Peyman Oreizy Autumn Omakase By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman, photographs by Peyman Oreizy The typeface family used throughout is Gill Sans designed by Eric Gill in 1929-30. TABLE OF CONTENTS Tatsu Nishino and Nishino by Hillel Cooperman Introduction by Tatsu Nishino Autumn Omakase 17 Oyster, Salmon, Scallop Appetizer 29 Kampachi Usuzukuri 39 Seared Foie Gras, Maguro, and Shiitake Mushroom with Red Wine Soy Reduction 53 Matsutake Dobinmushi 63 Dungeness Crab, Friseé, Arugula, and Fuyu Persimmon Salad with Sesame Vinaigrette 73 Hirame Tempura Stuffed with Uni, Truffle, and Shiso 85 Hamachi with Balsamic Teriyaki 95 Toro Sushi, Three Ways 107 Plum Wine Fruit Gratin The Making of Autumn Omakase Who Did What Invitation TATSU NISHINO AND NISHINO In the United States, ethnic cuisines generally fit into convenient and simplistic categories. Mexican food is one monolithic cuisine, as is Chinese, Italian, and of course Japanese. Every Japanese restaurant serves miso soup, various tempura items, teriyaki, sushi, etc. The fact that Japanese cuisine is multi-faceted (as are most cuisines) and quite diverse doesn’t generally come through to the public—the American homogenization machine reduces an entire culture’s culinary contributions to a simple formula that can fit on one menu. -

Takeout Menu

rice balls sandwich rice dishes ONIGIRI "RICE BALL" GYU DON $14 TOKYO PHILLY SANDO $14 thinley sliced beef simmered in sweet soy $3 each or two for $5 with onion, green peas and soy, onsen egg, pickled ginger over rice please pick flavor below Thinly sliced soy marinated beef with onion, swiss and cheddar cheese in local Sea Wolf house smoked shio koji salmon pain au lait bread with aonori fries. VEGETABLE mentai mayo TEN DON $11 ume shiso vegetable tempura over rice, sweet soy KATSU SANDO $13 $5 each or two for $9 deep fried pork katsu, cabbage, katsu sauce, TEN DON $13 Tenmusu karashi kewpie in local Sea Wolf pain au lait riceball with shrimp tempura, seaweed bread with aonori fries. shrimp tempura, vegetable tempura, over sweet soy rice, sweet soy Spam musubi EGG ON EGG SANDO $17 JAPANESE VEGETABLE House made spam, furikake, sesame egg sandwich with ikura (salmon caviar) CURRY $10 shallots and kewpie mayo n local Sea Wolf pain au lait bread with aonori fries. potato, celery, carrots, onion, side of rice add pork katsu for +4 osouzai "snacks" UNAGI DON $18 chilled soba "pour over" Japanese BBQ eel with sansho eel sauce TSUKEMONO $6 with dashi egg rolls (dashi maki tamago) on selection of house made pickled vegetables PLEASE ENJOY WITHIN 30 MIN AFTER RECEIVED top of rice GARLIC BUTTER EDAMAME $5 IKURA BUKKAKE SOBA $20 sauteed edamame with butter, parsley, garlic, black pepper, chili flake ikura, daikon, shiso, radish, wasabi, tempura flakes, kizami nori fried & tempura ADDICTIVE BAMBOO $5 Bamboo shoots marinated in our house made chili BLISTERED SHISHITO $7 oil with green onion, garlic, sesame and peanuts hot soba "dipping style" fried shishito peppers with yuzu kosho aioli HAWAIIAN MACARONI PLEASE ENJOY WITHIN 30 MIN AFTER RECEIVED SHRIMP TEMPURA $7 (2PC) SALAD $5 curry flavored macaroni salad with mayo, DUCK CURRY SEIRO SOBA $18 KABOCHA WINGS $8 cucumber dipping style hot soba, braised duck, eggplant, green Kabocha squash tempura with a pork demi curry, coconut milk, bell pepper, onion glaze reduction sauce, sesame seeds. -

Vegetables and Meals of Daimyo Living in Edo

Vegetables and the Diet of the Edo Period, Part 1 Vegetables and Meals of Daimyo Living in Edo By Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University) Introduction in which they were grown. The names given to egg- plant were also varied, including round eggplant, Most of the vegetables currently used in Japan were long eggplant, calabash-shaped eggplant, red egg- introduced from other countries at various points plant, white eggplant and black eggplant. throughout history. Vegetables native to Japan are The primary suppliers of fresh vegetables to the three very limited, and include udo (Japanese spikenard, largest consumer cities of Edo, Kyoto and Osaka Aralia cordata), mitsuba (Japanese wild parsley, were suburban farming villages. Buko Sanbutsu-shi Cryptotaenia japonica), myoga ginger (Zingiber (1824) is a record that lists agricultural products from mioga), fuki (giant butterbur, Petasites japonicus) and the Musashi region that included Edo. Vegetables are yamaimo (Japanese yam, Dioscorea japonica). The listed by the area in which they were grown: daikon domestic turnips, daikon radish, green onions, orien- radish and carrots in Nerima (present-day Nerima tal mustard (Brassica juncea), varieties of squash, ward, Tokyo), mizuna (Japanese mustard, Brassica and eggplant currently used in Japan were introduced rapa var. nipposinica), Chinese celery (Oenanthe from the Chinese mainland and Korean peninsula. javanica), mitsuba and edible chrysanthemum in Eventually, Danish squash, watermelon, chili peppers Senju (present-day Adachi ward, Tokyo), burdock and sweet potatoes came to Japan through trade with (Arctium lappa) in Iwatsuki (present-day Iwatsuki, Portugal during the 16th century, and carrots, celery, Saitama prefecture), taro and sweet potato in Kasai spinach, and edible chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum (present-day Edogawa ward, Tokyo), eggplant in coronarium) via trade with China during the Ming Komagome (present-day Toshima ward, Tokyo) and dynasty (1368–1644). -

How to Distinguish Amanita Smithiana from Matsutake and Catathelasma Species

VOLUME 57: 1 JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2017 www.namyco.org How to Distinguish Amanita smithiana from Matsutake and Catathelasma species By Michael W. Beug: Chair, NAMA Toxicology Committee A recent rash of mushroom poisonings involving liver failure in Oregon prompted Michael Beug to issue the following photos and information on distinguishing the differences between the toxic Amanita smithiana and edible Matsutake and Catathelasma. Distinguishing the choice edible Amanita smithiana Amanita smithiana Matsutake (Tricholoma magnivelare) from the highly poisonous Amanita smithiana is best done by laying the stipe (stem) of the mushroom in the palm of your hand and then squeezing down on the stipe with your thumb, applying as much pressure as you can. Amanita smithiana is very firm but if you squeeze hard, the stipe will shatter. Matsutake The stipe of the Matsutake is much denser and will not shatter (unless it is riddled with insect larvae and is no longer in good edible condition). There are other important differences. The flesh of Matsutake peels or shreds like string cheese. Also, the stipe of the Matsutake is widest near the gills Matsutake and tapers gradually to a point while the stipe of Amanita smithiana tends to be bulbous and is usually widest right at ground level. The partial veil and ring of a Matsutake is membranous while the partial veil and ring of Amanita smithiana is powdery and readily flocculates into small pieces (often disappearing entirely). For most people the difference in odor is very distinctive. Most collections of Amanita smithiana have a bleach-like odor while Matsutake has a distinctive smell of old gym socks and cinnamon redhots (however, not all people can distinguish the odors). -

Dynasty Weekend Dim Sum Menu

DIM SUM (A) HK$ Per Plate Double-boiled whole coconut soup with abalone and minced pork dumpling 148 Steamed Shanghainese minced pork dumplings 80 Deep-fried Shrimp and crabmeat toasts 80 Steamed shrimp dumpling 90 Steamed minced shrimp and pork dumpling 90 Steamed minced beef dumpling with vegetable 74 Deep-fried spring roll with taro 74 Barbecued pork bun 74 Glutinous rice flavored with shredded dried scallops and diced chicken 80 wrapped with a lotus leaf Smoked minced salmon tart baked with cheese 74 Black truffle sauce vegetarian dumpling 74 Shredded turnip baked puffs 74 Deep-fried mashed taro puffs with matsutake mushroom and minced chicken 80 Minced shrimp and assorted vegetables rice roll 120 Assorted mushrooms with bamboo fungus rice roll 120 Sliced Iberico pork liver rice roll 150 Barbecued pork with preserved vegetable rice roll 120 Steamed glutinous rice dumpling stuffed with assorted preserved meats 74 Spare rib flavored with black bean 80 Steamed chicken fillet, fish maw and black mushroom 80 Chicken feet flavored with black bean 74 All prices are subject to a 10% service charge. If you have any concerns regarding food allergies, please alert your server prior to ordering. RENAISSANCE HARBOUR VIEW HOTEL HONG KONG 1 HARBOUR ROAD, WANCHAI, HONG KONG T : (852) 2802 8888 F : (852) 2802 8833 WWW.RENAISSANCEHARBOURVIEWHK.COM DIM SUM (B) HK$ Per Plate Double-boiled whole coconut soup with abalone and minced pork dumpling 148 Steamed Shanghainese minced pork dumplings 80 Deep-fried shrimp and crabmeat toasts 80 Steamed shrimp dumpling -

Purely a Cookbook... Taming the Wild Mushroom a Culinary Guide To

Purely a Cookbook... Taming the Wild Mushroom A Culinary Guide to Market Foraging written by Arleen R. Bessette and Alen E. Bessette, University of Texas Press This cookbook was written for the novice mushroom hunter, someone who is “fearful about eating wild mushrooms because of the danger of being poisoned.” It brings the culinary delights of the wild mushroom to those who are beginning to learn to forage as they can hunt these mushrooms in their local, gourmet, or Asian grocery store. The mushrooms covered here are the white buttons (Agaricus bisporus aka A. brunnescens), King boletes (Boletus edulis), Oysters (Pleurotus ostreatus complex), Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius), morels (Morchella esculenta and M. elata aka M. angusticeps), paddy straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea), wood and cloud ears (Auricularia polytrichia and Auricularia auricular-judae), shiitakes (Lentinula edodes), enokitakes (Flammulina velutipes grown in the dark), White Matsutakes (Tricholoma magnivelare), black truffles (Tuber melanosporum), and wine cap Stropharias (Stropharia rugoso-annulata). This is quite an array of mushrooms. I’ve seen most of them in various stores; some fresh, some dried and some canned; although I haven’t seen wine cap Stropharias, though. There is a good range of recipes from fairly simple like enokitake and endive salad to gourmet delights like veal scallopine with mushrooms, chanterelle popovers, and shrimp and black truffle bisque. A Cook’s Book of Mushrooms written by Jack Czarnecki, Artisan Press, 1995 This cookbook is oriented mostly toward commercially available mushrooms but also has some wild mushroom recipes. The grocery store mushroom recipes can easily be adapted to work with wild mushrooms. -

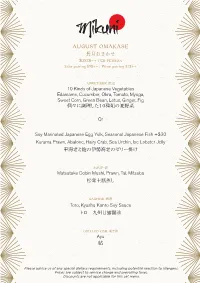

Mikuni-Omakase

AUGUST OMAKASE 長月おまかせ $208++ PER PERSON Sake pairing $98++ | Wine pairing $78++ WAGYU 和牛 A5 Tochigi Wagyu & Matsutake Sukiyaki Hot Pot APPETISER 前菜 10 Kinds of Japanese Vegetables A5栃木牛と松茸のすき焼き小鍋 Edamame, Cucumber, Okra, Tomato, Myoga, Sweet Corn, Green Bean, Lotus, Ginger, Fig 個々に調理した10種類の夏野菜 SUSHI 寿司 Toro Kawahagi Anago トロ 皮剥 穴子 Or DESSERT 甘味 Soy Marinated Japanese Egg Yolk, Seasonal Japanese Fish +$30 Nippon Summer Fruits, Elderflower Jelly, Pink Peach Sorbet Kuruma Prawn, Abalone, Hairy Crab, Sea Urchin, Ise Lobster Jelly 日本の果実のゼリーと桃のシャーベット 車海老と鮑の伊勢海老のゼリー掛け SOUP 碗 Matsutake Dobin Mushi, Prawn, Tai, Mitsuba 松茸土瓶蒸し SASHIMI 刺身 Toro, Kyushu Kanro Soy Sauce トロ 九州甘露醤油 GRILLED FISH 焼き物 Ayu 鮎 Please advise us of any special dietary requirements, including potential reaction to allergens. Prices are subject to service charge and prevailing taxes. Discounts are not applicable for this set menu. WAGYU 和牛 A5 Tochigi Wagyu & Matsutake Sukiyaki Hot Pot APPETISER 前菜 10 Kinds of Japanese Vegetables A5栃木牛と松茸のすき焼き小鍋 Edamame, Cucumber, Okra, Tomato, Myoga, Sweet Corn, Green Bean, Lotus, Ginger, Fig 個々に調理した10種類の夏野菜 SUSHI 寿司 Toro Kawahagi Anago トロ 皮剥 穴子 Or DESSERT 甘味 Soy Marinated Japanese Egg Yolk, Seasonal Japanese Fish +$30 Nippon Summer Fruits, Elderflower Jelly, Pink Peach Sorbet Kuruma Prawn, Abalone, Hairy Crab, Sea Urchin, Ise Lobster Jelly 日本の果実のゼリーと桃のシャーベット 車海老と鮑の伊勢海老のゼリー掛け SOUP 碗 Matsutake Dobin Mushi, Prawn, Tai, Mitsuba 松茸土瓶蒸し SASHIMI 刺身 Toro, Kyushu Kanro Soy Sauce トロ 九州甘露醤油 GRILLED FISH 焼き物 Ayu 鮎 Please advise us of any special dietary requirements, including potential reaction to allergens. Prices are subject to service charge and prevailing taxes. Discounts are not applicable for this set menu..