2015 16 Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 20 Catalog

20 ◆ 2019 Catalog S MITH C OLLEGE 2 019–20 C ATALOG Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 S MITH C OLLEGE C ATALOG 2 0 1 9 -2 0 Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 413-584-2700 2 Contents Inquiries and Visits 4 Advanced Placement 36 How to Get to Smith 4 International Baccalaureate 36 Academic Calendar 5 Interview 37 The Mission of Smith College 6 Deferred Entrance 37 History of Smith College 6 Deferred Entrance for Medical Reasons 37 Accreditation 8 Transfer Admission 37 The William Allan Neilson Chair of Research 9 International Students 37 The Ruth and Clarence Kennedy Professorship in Renaissance Studies 10 Visiting Year Programs 37 The Academic Program 11 Readmission 37 Smith: A Liberal Arts College 11 Ada Comstock Scholars Program 37 The Curriculum 11 Academic Rules and Procedures 38 The Major 12 Requirements for the Degree 38 Departmental Honors 12 Academic Credit 40 The Minor 12 Academic Standing 41 Concentrations 12 Privacy and the Age of Majority 42 Student-Designed Interdepartmental Majors and Minors 13 Leaves, Withdrawal and Readmission 42 Five College Certificate Programs 13 Graduate and Special Programs 44 Advising 13 Admission 44 Academic Honor System 14 Residence Requirements 44 Special Programs 14 Leaves of Absence 44 Accelerated Course Program 14 Degree Programs 44 The Ada Comstock Scholars Program 14 Nondegree Studies 46 Community Auditing: Nonmatriculated Students 14 Housing and Health Services 46 Five College Interchange 14 Finances 47 Smith Scholars Program 14 Financial Assistance 47 Study Abroad Programs 14 Changes in Course Registration 47 Smith Programs Abroad 15 Policy Regarding Completion of Required Course Work 47 Smith Consortial and Approved Study Abroad 16 Directory 48 Off-Campus Study Programs in the U.S. -

March 09 Newsletter

Reference NOTES A Program of the Minnesota Office of Higher Education and the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities March 2009 Minitex (not MINITEX) and MnKnows Bill DeJohn, Minitex Director Inside This Issue Over the next few months, you will be watching our migration to a new name, Minitex (upper and lower case on Minitex), and a new name for a new portal Minitex (not MINITEX) and MnKnows 1 site, MnKnows, (or, read it, Minnesota Knows, if you prefer). MnKnows will provide single-site access to Ada Comstock – Educator the MnLINK Gateway, ELM, Minnesota Reflections, and Transformer 1 AskMN, and the Research Project Calculator – the Minitex services used most by the general public. For more information about these changes, see the article Library Technology Conference “And, What’s in a Name: MINITEX to Minitex and a new one, MnKnows” in Re-cap Information Commons 2 Minitex E-NEWS #93: http://minitex.umn.edu/publications/enews/2009/093.pdf The Keynote Speech of Eric Lease Morgan 2 Ada Comstock – Educator and Transformer Library 2.0 and Google Apps 3 Carla Pfahl E-Resource Management 4 March is Women’s History Month, and we thought it What Everything Has to Do would be a good idea to highlight a Minnesotan who with Everything 4 played a part in history by reshaping the higher education system for women. Ada Comstock was born in 1876 and Library Technology Programs for raised in Moorhead, MN. After excelling in the various Baby Boomers and Beyond 4 schools Ada attended, she graduated from high school The Opposite of Linear: early and began her undergraduate career at the age of 16 Learning at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis in 1892. -

Weekend Program May 16-19, 2019 HOURS a Cell Phone

REUNION Weekend Program May 16-19, 2019 HOURS a cell phone. Anyone who is injured or becomes ill while on campus should seek Alumnae House medical attention at the Cooley Dickinson Thursday, 8:30 a.m.–9 p.m. Hospital, 30 Locust Street, 413-582-2000. elcome to Smith! We’re excited you’re here to celebrate Reunion Friday and Saturday, 8 a.m.–10 p.m. and the Smith friendships that have sustained you since graduation. Sunday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. W LOST AND FOUND Inquiries about articles lost on campus Registration/Check-In Hours Alumnae always tell us that one of the greatest gifts of their Smith may be made Thursday through Sunday Alumnae House Tent at the Campus Center information desk, experience is the deep connection they share with other Smithies. No Thursday, 4–9 p.m. 413-585-4801. On Monday, all unclaimed matter how much time passes, the bonds among Smith alumnae endure Friday, 8 a.m.–10 p.m. articles will be taken to the Alumnae and only grow stronger. Saturday, 8 a.m.–7 p.m. House. Smith College is not responsible for lost or stolen articles. SHUTTLE SERVICE This weekend is all about connection—a chance for all of us to come together for Smith. From the alumnae parade to Illumination Night to Shuttle service is provided for on-campus SPECIAL PROGRAM faculty presentations, we want you to once again experience the power transportation only. For shuttle service, Class of ’69 Exhibit call 413-585-2400. Representative Works of 13 Class of Smith, its place in the world, and its remarkable legacy of creating the of ’69 Visual Artists leaders and visionaries the world needs. -

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1 - December 31, 2001 L LEVI LOPAKA ESPERAS LAA, 27, of Wai'anae, died April 18, 2001. Born in Honolulu. A Mason. Survived by wife, Bernadette; daughter, Kassie; sons, Kanaan, L.J. and Braidon; parents, Corinne and Joe; brothers, Joshua and Caleb; sisters, Darla and Sarah. Memorial service 5 p.m. Monday at Ma'ili Beach Park, Tumble Land. Aloha attire. Arrangements by Ultimate Cremation Services of Hawai'i. [Adv 29/4/2001] Mabel Mersberg Laau, 92, of Kamuela, Hawaii, who was formerly employed with T. Doi & Sons, died Wednesday April 18, 2001 at home. She was born in Puako, Hawaii. She is survived by sons Jack and Edward Jr., daughters Annie Martinson and Naomi Kahili, sister Rachael Benjamin, eight grandchildren, 12 great-grandchildren and a great-great-grandchild. Services: 11 a.m. Tuesday at Dodo Mortuary. Call after 10 a.m. Burial: Homelani Memorial Park. Casual attire. [SB 20/4/2001] PATRICIA ALFREDA LABAYA, 60, of Wai‘anae, died Jan. 1, 2001. Born in Hilo, Hawai‘i. Survived by husband, Richard; daughters, Renee Wynn, Lucy Evans, Marietta Rillera, Vanessa Lewi, Beverly, and Nadine Viray; son, Richard Jr.; mother, Beatrice Alvarico; sisters, Randolyn Marino, Diane Whipple, Pauline Noyes, Paulette Alvarico, Laureen Leach, Iris Agan and Rusielyn Alvarico; brothers, Arnold, Francis and Fredrick Alvarico; 17 grandchildren; four great-grandchildren. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Wednesday at Nu‘uanu Mortuary, service 7 p.m. Visitation also 8:30 to 10:30 a.m. Thursday at the mortuary; burial to follow at Hawai‘i State Veterans Cemetery. -

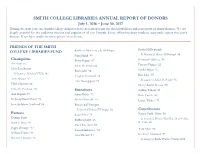

2017 Annual Report of Donors

SMITH COLLEGE LIBRARIES ANNUAL REPORT OF DONORS July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 During the past year, the Smith College Libraries have benefited from the thoughtfulness and generosity of many donors. We are deeply grateful for the enduring interest and support of all our Friends. Every effort has been made to accurately report this year’s donors. If we have made an error, please let us know. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRIENDS OF THE SMITH Kevin McDonough COLLEGE LIBRARIES FUND Kathleen McCartney & Bill Hagen Nina Munk ’88 In Memory of Marcia McDonough ’54 Champions Betsy Pepper ’67 Elizabeth McEvoy ’96 Anonymous Sarah M. Pritchard Frances Pepper ’62 Mary-Lou Boone Ruth Solie ’64 Sandra Rippe ’67 In honor of Martha G.Tolles ’43 Virginia Thiebaud ’72 Rita Saltz ’60 Anne Brown ’62 Amy Youngquist ’74 In memory of Sarah M. Bolster ’50 Edith Dinneen ’40 Cheryl Stadel-Bevans ’90 Christine Erickson ’65 Sustainers Audrey Tanner ’91 Ann Kaplan ’67 Susan Baker ’79 Ruth Turner ’46 M. Jenny Kuntz Frost ’78 Sheila Cleworth ’55 Lynne Withey ’70 Joan Spillsbury Stockard ’53 Rosaleen D'Orsogna In honor of Rebecca D'Orsogna ’02 Contributors Patrons Susan Flint ’78 Nancy Veale Ahern ’58 Deanna Bates Barbara Judge ’46 In memory of Marian Mcmillan ’26 & Gladys Mary F. Beck ’56 B. Veale ’26 Paula Kaufman ’68 Peggy Danziger ’62 Susan Lindenauer ’61 Amy Allen ’90 Stefanie Frame ’98 Ann Mandel ’53 Kathleen Anderson ’57 Marianne Jasmine ’85 In memory of Bertha Watters Tildsley 1894 Elise Barack ’71 Kate Kelly ‘73 Sally Rand ‘47 In memory of Sylvia Goetzl ’71 Brandy King ’01 Katy Rawdon ’95 Linda Beech ’62 Claudia Kirkpatrick ’65 Eleanor Ray Sarah Bellrichard ’94 Jocelyne Kolb ’72 In memory of Eleanor B. -

During the Second-Wave Feminist Movement: Katharine Rea a Historical Case Study

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 A "Quiet Activist" During The Second-Wave Feminist Movement: Katharine Rea A Historical Case Study Sara R. Kaiser University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Kaiser, Sara R., "A "Quiet Activist" During The Second-Wave Feminist Movement: Katharine Rea A Historical Case Study" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1041. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1041 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “QUIET ACTIVIST” DURING THE SECOND-WAVE FEMINIST MOVEMENT: KATHARINE REA A HISTORICAL CASE STUDY A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the department of Leadership and Counselor Education The University of Mississippi By SARA R. KAISER August 2013 Copyright Sara R. Kaiser 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The purpose of this historical case study dissertation is to discover the story of Dr. Katharine Rea in her role as dean of women and later faculty member in the higher education and student personnel program at the University of Mississippi. As the dean of women in the 1960s Rea was responsible for the well-being and quality of the educational experience of the women students at UM. Rea pursued leadership opportunities for the women students through academic honor societies, and student government. -

A History of the Conferences of Deans of Women, 1903-1922

A HISTORY OF THE CONFERENCES OF DEANS OF WOMEN, 1903-1922 Janice Joyce Gerda A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2004 Committee: Michael D. Coomes, Advisor Jack Santino Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen M. Broido Michael Dannells C. Carney Strange ii „ 2004 Janice Joyce Gerda All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael D. Coomes, Advisor As women entered higher education, positions were created to address their specific needs. In the 1890s, the position of dean of women proliferated, and in 1903 groups began to meet regularly in professional associations they called conferences of deans of women. This study examines how and why early deans of women formed these professional groups, how those groups can be characterized, and who comprised the conferences. It also explores the degree of continuity between the conferences and a later organization, the National Association of Deans of Women (NADW). Using evidence from archival sources, the known meetings are listed and described chronologically. Seven different conferences are identified: those intended for deans of women (a) Of the Middle West, (b) In State Universities, (c) With the Religious Education Association, (d) In Private Institutions, (e) With the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, (f) With the Southern Association of College Women, and (g) With the National Education Association (also known as the NADW). Each of the conferences is analyzed using seven organizational variables: membership, organizational structure, public relations, fiscal policies, services and publications, ethical standards, and affiliations. Individual profiles of each of 130 attendees are provided, and as a group they can be described as professional women who were both administrators and scholars, highly-educated in a variety of disciplines, predominantly unmarried, and active in social and political causes of the era. -

President Drew Gilpin Faust by John S

A Scholar in the House President Drew Gilpin Faust by john s. rosenberg radition and the twenty-first century were tas crest backed up the bust. Carved into the heraldic paneling tangled together in Barker Center’s Thompson Room on either side of the fireplace were great Harvard names: T on the afternoon of February 11, when Drew Gilpin Bulfinch and Channing, Lowell and Longfellow, Agassiz and Faust conducted her first news conference as Har- Adams, Holmes and Allston. Huge portraits of iconic Harvar- vard’s president-elect. dians hung on the walls: astronomer Percival Lowell, for science; Daniel Chester French’s bronze bust of John Harvard, perched Le Baron Russell Briggs, professor of English and of rhetoric and on the mantelpiece of the enormous fireplace behind the lectern, oratory, a humanist and University citizen who served as dean of peered down on Faust and the other speakers—and a stone veri- Harvard College and—nearly simultaneously—dean of the Fac- 24 July - August 2007 April 2007: Drew Gilpin Faust at her then-o∞ce as dean of the Radcli≠e Institute for Advanced Study, photographed by Jim Harrison ulty of Arts and Sciences and (she is an accomplished historian), to an extent not matched president of Radcli≠e Col- since chemist James Bryant Conant became president in 1933. lege; and, from the world of Second, because Faust has been dean of the Radcli≠e Institute public service, Theodore for Advanced Study since 2001, Harvard has turned to one of its Roosevelt, A.B. 1880, LL.D. own—the first truly internal candidate since Derek Bok, then 1902, an Overseer from 1895 dean of Harvard Law School, became president in 1971. -

Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History

Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ulrich, Laurel, ed. 2004. Yards and gates: gender in Harvard and Radcliffe history. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4662764 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History Edited by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich i Contents Preface………………………………………………………………………………........………ix List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………………………......xi Introduction: “Rewriting Harvard’s History” Laurel Thatcher Ulrich..…………………….…………………………………….................1 1. BEFORE RADCLIFFE, 1760-1860 Creating a Fellowship of Educated Men Forming Gentlemen at Pre-Revolutionary Harvard……………………………………17 Conrad Edick Wright Harvard Once Removed The “Favorable Situation” of Hannah Winthrop and Mercy Otis Warren…………………. 39 Frances Herman Lord The Poet and the Petitioner Two Black Women in Harvard’s Early History…………………………………………53 Margot Minardi Snapshots: From the Archives Anna Quincy Describes the “Cambridge Worthies” Beverly Wilson Palmer ………………………………....................................................69 “Feminine” Clothing at Harvard in the 1830s Robin McElheny…………………………………………………………………….…75 -

It's My Retirement Money--Take Good Care of It: the TIAA-CREF Story

INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF USE TIAA-CREF and the Pension Research Council (PRC) of the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, are pleased to provide this digital edition of It's My Retirement Money—Take Good Care Of It: The TIAA-CREF Story, by William C. Greenough, Ph.D. (Homewood, IL: IRWIN for the Pension Research Council of the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 1990). The book was digitized by TIAA-CREF with the permission of the Pension Research Council, which is the copyright owner of the print book, and with the permission of third parties who own materials included in the book. Users may download and print a copy of the book for personal, non- commercial, one-time, informational use only. Permission is not granted for use on third-party websites, for advertisements, endorsements, or affiliations, implied or otherwise, or to create derivative works. For information regarding permissions, please contact the Pension Research Council at [email protected]. The digital book has been formatted to correspond as closely as possible to the print book, with minor adjustments to enhance readability and make corrections. By accessing this book, you agree that in no event shall TIAA or its affiliates or subsidiaries or PRC be liable to you for any damages resulting from your access to or use of the book. For questions about Dr. Greenough or TIAA-CREF's history, please email [email protected] and reference Greenough book in the subject line. ABOUT THE AUTHOR... [From the original book jacket] An economist, Dr. Greenough received his Ph.D. -

PRESS RELEASE the Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 732-6200

PRESS RELEASE The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 732-6200 www.hsp.org For Immediate Release Media Contact: Mary Ann Coyle 215-732-6200, ext. 220 [email protected] The Historical Society of Pennsylvania presents Founder’s Award to Local Teacher and Three Nationally Recognized Educators Philadelphia-- The Historical Society of Pennsylvania will present its prestigious Founder’s Award at its annual Founder’s Awards dinner on Saturday, April 17, at the Society. This year’s awards honor four individuals for their Contributions to Historical Education: Donald G. Brownlow, Mary Maples Dunn, Sheldon Hackney, and Gary B. Nash. Donald G. Brownlow, of The Haverford School, was nominated for the Founder’s Award as a particularly distinguished and effective Philadelphia area teacher. He is renowned for his ability to stimulate students’ interest and enthusiasm in history, his creativity in addressing historical issues, and his legacy of nurturing student historians. Mary Maples Dunn, co-executive of the American Philosophical Society, has shaped history’s education and future as a professor at Bryn Mawr College, as President of Smith College, as director of Radcliffe College’s Schlesinger Library, and as Acting Dean of the Radcliffe Institute. She is known as a superbly engaging teacher with lasting influence on students. Sheldon Hackney has served as chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities under President Clinton, president of the University of Pennsylvania, provost of Princeton University, and president of Tulane University. Now teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, Professor Hackney is a distinguished historian of the American South, the Civil Rights Movement, and America of the 1960s. -

2014 15 Catalog

15 ◆ Catalog 2014 S MITH C OLLEGE 2 0 1 4 – 1 5 C ATALOG Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 Notice of Nondiscrimination 2014–15 Class Schedule Smith College is committed to maintaining a diverse community in an atmosphere of mutual respect and appreciation of differences. A student may not elect more than one course Although you must know how to read the Smith College does not discriminate in its edu- in a single time block except in rare cases that course schedule, do not let it shape your pro- cational and employment policies on the bases of involve no actual time conflict. gram initially. In September, you should first race, color, creed, religion, national/ethnic origin, Normally, each course is scheduled to fit choose a range of courses, and then see how sex, sexual orientation, age, or with regard to the into one set of lettered blocks in this time grid. they can fit together. Student and faculty advis- bases outlined in the Veterans Readjustment Act Most meet two or three times a week on alter- ers will help you. and the Americans with Disabilities Act. nate days. Smith’s admission policies and practices are guided by the same principle, concerning women applying to the undergraduate program and all applicants to the graduate programs. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday For more information, please contact the ad- viser for equity complaints, College Hall 103, 413- A 8–8:50 a.m. A 8–8:50 a.m. A 8–8:50 a.m. B 8–8:50 a.m. A 8–8:50 a.m.