President Drew Gilpin Faust by John S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy, Race, and Multiculturalism

PHILOSOPHY 232: PHILOSOPHY ‘RACE,’ AND MULTICULTURALISM winter/spring ‘14 Larry Blum W-5-012 Office Hours: Tuesday 3:20-4:20 Thursday 12:50-1:50 or by appointment phone: 617-287-6532 (also voice mail) e-mail: [email protected] REQUIRED BOOKS: Books you will need (and are in UMass bookstore): 1. W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk ("Du Bois") [There are many different editions of this book. The page numbers I have given you are from the Dover edition, which is the least expensive edition and is the one in the UMass bookstore. But you can easily figure out what the reading is no matter which edition you have.] 2. Amy Gutmann (ed.), Multiculturalism ("Gutmann")[you won’t need this until later in the course] [These books are also on reserve at the Reserve Desk at Healey Library.] Course website: All course material other than books will be posted on the course website. The site will also have announcements; assignments; handouts; this syllabus, and other materials related to the course. You should check the website regularly and especially if you miss class. The URL of the site is: http://www.BlumPhilosophy.com. Click on the “Teaching” heading at the top under the photo of UMass. A list of courses I teach will show up on the left. Click on this course. The titles of the course readings will show up under “readings”, organized by “class 4,” “class 7,” etc. Click on the reading you want and it will show up. (This numbering of the “classes” does not correspond to the actual class the reading will be discussed!! Use the syllabus to find out on what date a reading will be discussed.) **Almost all readings on the website will also be on Electronic Reserves (marked “ERes” on the syllabus), accessible on the Healey Library website. -

The Communitarian Critique of Liberalism Author(S): Michael Walzer Reviewed Work(S): Source: Political Theory, Vol

The Communitarian Critique of Liberalism Author(s): Michael Walzer Reviewed work(s): Source: Political Theory, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb., 1990), pp. 6-23 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/191477 . Accessed: 24/08/2012 12:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Sage Publications, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Political Theory. http://www.jstor.org THE COMMUNITARIAN CRITIQUE OF LIBERALISM MICHAEL WALZER Institutefor A dvanced Study 1. Intellectualfashions are notoriously short-lived, very much like fashions in popularmusic, art, or dress.But thereare certainfashions that seem regularlyto reappear. Like pleated trousers or short skirts, they are inconstant featuresof a largerand more steadily prevailing phenomenon - in this case, a certainway of dressing. They have brief but recurrent lives; we knowtheir transienceand excepttheir return. Needless to say,there is no afterlifein whichtrousers will be permanentlypleated or skirtsforever short. Recur- renceis all. Althoughit operatesat a muchhigher level (an infinitelyhigher level?) of culturalsignificance, the communitarian critique of liberalismis likethe pleatingof trousers:transient but certainto return.It is a consistently intermittentfeature of liberalpolitics and social organization.No liberal successwill make it permanently unattractive. -

Bulletinvolume 106, Number 3 Feb

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY BULLETINVolume 106, Number 3 Feb. 16, 2017 President Eisgruber speaks out against federal immigration executive order rinceton President Christopher L. Since its early days, when the College Graduate School Sanjeev Kulkarni have students, faculty and staff know how Eisgruber issued a statement of New Jersey recruited a transforma- issued messages providing preliminary to obtain information or help. to the University community P tive president from Scotland, this information about the order and its Princeton will also continue to that expressed his concerns over an University has depended on America’s consequences. Staff members in the executive order on immigration that safeguard personal information about President Trump issued Jan. 27. ability to attract and engage with Davis International Center and else- non-citizens as it does for all of its Eisgruber also drafted, along with talented people from around the world. where on campus are working around students, faculty and staff. As I noted University of Pennsylvania President Princeton today bene ts the clock to assess the full in a previous letter to the community, Amy Gutmann, a letter that they and tremendously from impact of the order and Princeton has policies in place to 46 other college and university presi- the presence of Princeton today to aid and counsel dents and chancellors sent to Trump protect the privacy of every member extraordinary indi- members of our on Feb. 2. benefi ts tremendously of the University community. We do In his statement to the Princeton viduals of diverse community, includ- not disclose private information about community on Jan. 29, Eisgruber nationalities from the presence ing those who our students, faculty or staff to law explained University policies for and faiths, and of extraordinary are currently out- enforcement of cers unless we are safeguarding personal information we will support side the United about non-citizens and noted resources presented with a valid subpoena or them vigorously. -

Weekend Program May 16-19, 2019 HOURS a Cell Phone

REUNION Weekend Program May 16-19, 2019 HOURS a cell phone. Anyone who is injured or becomes ill while on campus should seek Alumnae House medical attention at the Cooley Dickinson Thursday, 8:30 a.m.–9 p.m. Hospital, 30 Locust Street, 413-582-2000. elcome to Smith! We’re excited you’re here to celebrate Reunion Friday and Saturday, 8 a.m.–10 p.m. and the Smith friendships that have sustained you since graduation. Sunday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. W LOST AND FOUND Inquiries about articles lost on campus Registration/Check-In Hours Alumnae always tell us that one of the greatest gifts of their Smith may be made Thursday through Sunday Alumnae House Tent at the Campus Center information desk, experience is the deep connection they share with other Smithies. No Thursday, 4–9 p.m. 413-585-4801. On Monday, all unclaimed matter how much time passes, the bonds among Smith alumnae endure Friday, 8 a.m.–10 p.m. articles will be taken to the Alumnae and only grow stronger. Saturday, 8 a.m.–7 p.m. House. Smith College is not responsible for lost or stolen articles. SHUTTLE SERVICE This weekend is all about connection—a chance for all of us to come together for Smith. From the alumnae parade to Illumination Night to Shuttle service is provided for on-campus SPECIAL PROGRAM faculty presentations, we want you to once again experience the power transportation only. For shuttle service, Class of ’69 Exhibit call 413-585-2400. Representative Works of 13 Class of Smith, its place in the world, and its remarkable legacy of creating the of ’69 Visual Artists leaders and visionaries the world needs. -

Our 'Star' Performer

News OCTOBER 2013 Volume 20 No. 1 Our ‘Star’ performer A new focus for Research, Innovation and Enterprise 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction As a research-intensive University which aims to be among the top 100 universities in the world, our commitment to research, partnership – we are already leading innovation and enterprise is crucial. the way. Finally, one of the major planks of our work is our international outlook. “ This edition of Cardiff News Professor Jenny Kitzinger from appointment under the Welsh provides a brief insight into this our School of Journalism, Media Government’s flagship Sêr Cymru You’ll meet members of our work and our plans for this key area and Cultural Studies sets out how programme and how our world- European Office who are working of University activity over the next her pioneering work into decision leading Cardiff expert in the genetics alongside academics from across few years. making for people in a vegetative of Alzheimer’s has been brought into Cardiff University to make sure that state is raising greater awareness the heart of Welsh Government to we are positioned as the best and get In this edition you’ll get a snapshot of this emotive issue and helping direct science policy. a fair chance of accessing funding in of how our research is already having inform future practice. the next round, as we look towards a major impact. From improving The University’s Vice-Chancellor, Horizon 2020. labour relations in world ports to You’ll also learn how our growing Professor Colin Riordan also providing the evidence base for a reputation internationally is helping introduces the concept of the Cardiff University has set itself the roll-out of health checks for people attract some of the world’s best Innovation System and sets out what next five years to ensure our research with learning disabilities. -

Harvard Ed Portal

Harvard University’s Annual Cooperation Agreements Report with the City of Boston ’16–’17 july 1, 2016 – june 30, 2017 Annual Report ’16–’17 What’s Inside Harvard is fortunate to be a part harvard ed portal 2 of the Allston community and to be arts & culture 4 engaged in thoughtful partnerships workforce & economic development 6 faculty speaker series 8 that demonstrate what it means to be harvardx for allston 10 neighbors. We are learning together, youth programming 12 creating together, and continuing to public school partnerships 14 discover the transformative power health & wellness 16 of our collaboration. housing 18 Harvard es afortunada por formar parte de la comunidad de Allston y public realm 20 participar en sociedades consideradas que demuestran lo que significa ser vecinos. Estamos aprendiendo juntos, creando harvard allston 22 juntos, y continuamos revelando el poder partnership fund transformador de nuestra colaboración. beyond the agreements 24 哈佛有幸成为Allston 社区的一部分, 并参与周详的合作伙伴关系,以表现作 partnerships 26 为邻居的含义。 我们一起学习,共同创 造,且持续展示合作所带来的变革性力 appendices 28 appendix a: 28 cooperation agreement É uma sorte Harvard fazer parte da budget overview comunidade de Allston, e assim se appendix b: 30 envolver em parcerias bem ponderadas status of cooperation agreements que demonstram o espírito de boa appendix c: 37 vizinhança. Estamos aprendendo housing stabilization fund update juntos, estamos criando juntos, e continuamos a revelar o poder appendix d: 38 transformador da nossa colaboração. community programming catalog july 2016 – june 2017 – drew gilpin faust president of harvard university lincoln professor of history HARVARD HAS A VALUED, longtime partnership with the Allston-Brighton neighborhood and the City of Boston. -

To View / Print the Inauguration of President Gutmann

Dr. Amy Gutmann October 15, 2004 Irvine Auditorium Photo by Stuart Watson Stuart by Photo ALMANAC SUPPLEMENT October 19, 2004 S-1 www.upenn.edu/almanac The Inaugural Ceremony I am honored to present to you the follow- but as a leader and a motivator. We found all Invocation ing speakers who bring greetings to President of this in Dr. Gutmann. She has developed a Rev. William C. Gipson Gutmann from their respective constituencies: powerful vision about the contribution that uni- University Chaplain Charles W. Mooney, on behalf of the faculty; Ja- versities can make to society and democracy. I Sacred Fire, Revelation Light, Fount of son Levine and Simi Wilhelm, on behalf of the have met so many students who already feel a Wisdom, Sojourner Spirit Companion of the students; Rodney Robinson and Sylvie Beauvais special connection with Dr. Gutmann through Despairing Disinherited of the Earth—All Gra- on behalf of the administration and staff. her writings. cious God, As a leader, Dr. Gutmann brings new energy, On this Inauguration Day for Pennʼs distin- Greetings optimism, and inspiration to Penn. Her Inaugu- guished eighth President, Dr. Amy Gutmann, we ral theme, Rising to the Challenges of a Diverse celebrate Penn—for the boldness of its academic Charles W. Mooney Democracy, recognizes many issues that we adventures, its electric intellectual inquiry, its Chair, Faculty Senate face today. In just the short time she has been faithfulness to committed citizenship in West Greetings from the faculty of the University here, Dr. Gutmann has motivated students to Philadelphia, the City, the Commonwealth, the of Pennsylvania. -

Public Commemoration of the Civil War and Monuments to Memory: the Triumph of Robert E

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Public Commemoration of the Civil War and Monuments to Memory: The Triumph of Robert E. Lee and the Lost Cause A Dissertation Presented By Edward T O’Connell to The Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University August 2008 Copyright by Edward Thomas O’Connell 2008 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Edward T O’Connell We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Wilbur Miller, Professor, Department of History, Dissertation Advisor Herman Lebovics, Professor, Department of History, Chairperson of Defense Nancy Tomes, Chair and Professor, Department of History Jenie Attie, Assistant Professor, C.W. Post College of Long Island University, Outside Member This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School. Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Public Commemoration and Monuments to Memory: The Triumph of Robert E. Lee and the Lost Cause by Edward T. O’Connell Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2008 This dissertation examines the significance of the Virginia Memorial located on the former battlefield of the Gettysburg Military Park in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Dedicated on June 8, 1917 and prominently featuring an equestrian image of Robert E. Lee, this work of public commemorative art represents a dominant voice in the dialogue of the constructed public memory of the causes and the consequences of the Civil War. -

PAS WEEKLY UPDATE WEEK of May 7, 2018 Mr

PAS WEEKLY UPDATE WEEK OF May 7, 2018 Mr. Farrell, Principal Thank you for coming out to our inaugural art celebraton last Thursday– Upcoming Events Celebratng the Art of Penn Alexander. We thank our planning commitee and the Home & School Associaton (HSA) Teacher Appreciaton Week for their commitment to Art programming at PAS! Monday, May 7th- Friday, May 11th Home & School Associaton (HSA) Meetng School District Parent & Guardian Survey We would love to hear your feedback! We ask that you take some tme and com- Tue., May 8th 6:00-7PM plete the School District of Philadelphia 2018 Parent & Guardian Survey now availa- ble through June 23rd. You will need your student’s ID number to access the survey, Kindergarten Open House ID numbers can be found on your child’s latest report card. Thur., May 10th 9:00-10AM Moving? Moving? Not returning to PAS next Fall? If you are Pretzel Friday ($1) planning to relocate, or not return to Penn Alexander Fri., May 11th next Fall, please contact the ofce with a writen leter as soon as possible. This informaton will assist Dinner & Bingo Night us in planning and reorganizing for the upcoming school-year. We have a number of students on our Fri., May 11th 5:30-8PM wait-list for each grade. Thanks for your communica- ton. Interim Reports (Grs. 5-8) Monday, May 14th Home and School Associaton (May 8th) Atenton 4th & 5th Grade Families– The May Home and School (HSA) meetng , on Tuesday, May 9th 6-7PM, will Electon Day, School Closed feature our 5th grade & Middle School teachers. -

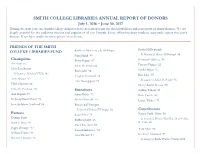

2017 Annual Report of Donors

SMITH COLLEGE LIBRARIES ANNUAL REPORT OF DONORS July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 During the past year, the Smith College Libraries have benefited from the thoughtfulness and generosity of many donors. We are deeply grateful for the enduring interest and support of all our Friends. Every effort has been made to accurately report this year’s donors. If we have made an error, please let us know. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRIENDS OF THE SMITH Kevin McDonough COLLEGE LIBRARIES FUND Kathleen McCartney & Bill Hagen Nina Munk ’88 In Memory of Marcia McDonough ’54 Champions Betsy Pepper ’67 Elizabeth McEvoy ’96 Anonymous Sarah M. Pritchard Frances Pepper ’62 Mary-Lou Boone Ruth Solie ’64 Sandra Rippe ’67 In honor of Martha G.Tolles ’43 Virginia Thiebaud ’72 Rita Saltz ’60 Anne Brown ’62 Amy Youngquist ’74 In memory of Sarah M. Bolster ’50 Edith Dinneen ’40 Cheryl Stadel-Bevans ’90 Christine Erickson ’65 Sustainers Audrey Tanner ’91 Ann Kaplan ’67 Susan Baker ’79 Ruth Turner ’46 M. Jenny Kuntz Frost ’78 Sheila Cleworth ’55 Lynne Withey ’70 Joan Spillsbury Stockard ’53 Rosaleen D'Orsogna In honor of Rebecca D'Orsogna ’02 Contributors Patrons Susan Flint ’78 Nancy Veale Ahern ’58 Deanna Bates Barbara Judge ’46 In memory of Marian Mcmillan ’26 & Gladys Mary F. Beck ’56 B. Veale ’26 Paula Kaufman ’68 Peggy Danziger ’62 Susan Lindenauer ’61 Amy Allen ’90 Stefanie Frame ’98 Ann Mandel ’53 Kathleen Anderson ’57 Marianne Jasmine ’85 In memory of Bertha Watters Tildsley 1894 Elise Barack ’71 Kate Kelly ‘73 Sally Rand ‘47 In memory of Sylvia Goetzl ’71 Brandy King ’01 Katy Rawdon ’95 Linda Beech ’62 Claudia Kirkpatrick ’65 Eleanor Ray Sarah Bellrichard ’94 Jocelyne Kolb ’72 In memory of Eleanor B. -

Women at Harvard

A W M Some people (including Dr. Summers, Prof. Pinker, and some discriminative value in certain fields, such the authors of the much-discussed book The Bell Curve) say or as professional aptitude, but only as measures of imply that IQ scores are normally distributed. Inferences about unusual intellectual capacity. Intellectual ability, extreme upper tails are sometimes based on that assumption. however, is only partially related to general intelli- Actually, the normality holds only approximately. gence. Exceptional intellectual ability is itself a kind For the WAIS, inferences about extreme upper tails of special ability. based on normality, as hazarded by Dr. Summers, would be unjustified because the test has an upper ceiling score 3 2/3 If one does assume that the scores are normally distrib- standard deviations above the mean (ceiling = IQ of 155, on uted, then in a typical standardizing sample of about 2000 the WAIS and WAIS-III; Wechsler tests have a standard people, the expected number of people with scores above deviation of 15 around the mean score of 100). Moreover, the 155 ceiling would be only about 1/4 of 1 person. Wechsler had long ago cautioned against seeing too close a The floor for WAIS scores, set at 35 or 45 in earlier ver- relation between extremely high IQ score and attainment in sions, is 0 in the WAIS-III, so that some scores can indicate science or other intellectual pursuits, as perhaps implied extreme mental retardation (or, anecdotally, failure of the by Dr. Summers. The Matarazzo edition of Wechsler says tester to gain any rapport with the testee). -

Academics and the Psychological Contract: the Formation and Manifestation of the Psychological Contract Within the Academic Role

University of Huddersfield Repository Johnston, Alan Academics and the Psychological Contract: The formation and manifestation of the Psychological Contract within the academic role. Original Citation Johnston, Alan (2021) Academics and the Psychological Contract: The formation and manifestation of the Psychological Contract within the academic role. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35485/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Academics and the Psychological Contract: The formation and manifestation of the Psychological Contract within the academic role. ALAN JOHNSTON A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration 8th February 2021 1 Declaration I, Alan Johnston, declare that I am the sole author of this thesis.