Data-Mining Probabilists Or Experimental Determinists?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cos513 Lecture 2 Conditional Independence and Factorization

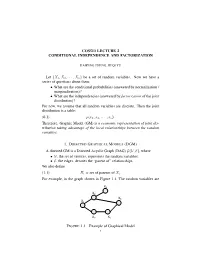

COS513 LECTURE 2 CONDITIONAL INDEPENDENCE AND FACTORIZATION HAIPENG ZHENG, JIEQI YU Let {X1,X2, ··· ,Xn} be a set of random variables. Now we have a series of questions about them: • What are the conditional probabilities (answered by normalization / marginalization)? • What are the independencies (answered by factorization of the joint distribution)? For now, we assume that all random variables are discrete. Then the joint distribution is a table: (0.1) p(x1, x2, ··· , xn). Therefore, Graphic Model (GM) is a economic representation of joint dis- tribution taking advantage of the local relationships between the random variables. 1. DIRECTED GRAPHICAL MODELS (DGM) A directed GM is a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) G(V, E), where •V, the set of vertices, represents the random variables; •E, the edges, denotes the “parent of” relationships. We also define (1.1) Πi = set of parents of Xi. For example, in the graph shown in Figure 1.1, The random variables are X4 X4 X2 X2 X 6 X X1 6 X1 X3 X5 X3 X5 XZY XZY FIGURE 1.1. Example of Graphical Model 1 Y X Y Y X Y XZZ XZZ Y XYY XY XZZ XZZ XZY XZY 2 HAIPENG ZHENG, JIEQI YU {X1,X2 ··· ,X6}, and (1.2) Π6 = {X2,X3}. This DAG represents the following joint distribution: (1.3) p(x1:6) = p(x1)p(x2|x1)p(x3|x1)p(x4|x2)p(x5|x3)p(x6|x2, x5). In general, n Y (1.4) p(x1:n) = p(xi|xπi ) i=1 specifies a particular joint distribution. Note here πi stands for the set of indices of the parents of i. -

Bayesian Networks

Bayesian Networks Read R&N Ch. 14.1-14.2 Next lecture: Read R&N 18.1-18.4 You will be expected to know • Basic concepts and vocabulary of Bayesian networks. – Nodes represent random variables. – Directed arcs represent (informally) direct influences. – Conditional probability tables, P( Xi | Parents(Xi) ). • Given a Bayesian network: – Write down the full joint distribution it represents. • Given a full joint distribution in factored form: – Draw the Bayesian network that represents it. • Given a variable ordering and some background assertions of conditional independence among the variables: – Write down the factored form of the full joint distribution, as simplified by the conditional independence assertions. Computing with Probabilities: Law of Total Probability Law of Total Probability (aka “summing out” or marginalization) P(a) = Σb P(a, b) = Σb P(a | b) P(b) where B is any random variable Why is this useful? given a joint distribution (e.g., P(a,b,c,d)) we can obtain any “marginal” probability (e.g., P(b)) by summing out the other variables, e.g., P(b) = Σa Σc Σd P(a, b, c, d) Less obvious: we can also compute any conditional probability of interest given a joint distribution, e.g., P(c | b) = Σa Σd P(a, c, d | b) = (1 / P(b)) Σa Σd P(a, c, d, b) where (1 / P(b)) is just a normalization constant Thus, the joint distribution contains the information we need to compute any probability of interest. Computing with Probabilities: The Chain Rule or Factoring We can always write P(a, b, c, … z) = P(a | b, c, …. -

(Ω, F,P) Be a Probability Spac

Lecture 9: Independence, conditional independence, conditional distribution Definition 1.7. Let (Ω, F,P ) be a probability space. (i) Let C be a collection of subsets in F. Events in C are said to be independent if and only if for any positive integer n and distinct events A1,...,An in C, P (A1 ∩ A2 ∩···∩ An)= P (A1)P (A2) ··· P (An). (ii) Collections Ci ⊂ F, i ∈ I (an index set that can be uncountable), are said to be independent if and only if events in any collection of the form {Ai ∈ Ci : i ∈ I} are independent. (iii) Random elements Xi, i ∈ I, are said to be independent if and only if σ(Xi), i ∈ I, are independent. A useful result for checking the independence of σ-fields. Lemma 1.3. Let Ci, i ∈ I, be independent collections of events. Suppose that each Ci has the property that if A ∈ Ci and B ∈ Ci, then A∩B ∈ Ci. Then σ(Ci), i ∈ I, are independent. Random variables Xi, i =1, ..., k, are independent according to Definition 1.7 if and only if k F(X1,...,Xk)(x1, ..., xk)= FX1 (x1) ··· FXk (xk), (x1, ..., xk) ∈ R Take Ci = {(a, b] : a ∈ R, b ∈ R}, i =1, ..., k If X and Y are independent random vectors, then so are g(X) and h(Y ) for Borel functions g and h. Two events A and B are independent if and only if P (B|A) = P (B), which means that A provides no information about the probability of the occurrence of B. Proposition 1.11. -

A Bunched Logic for Conditional Independence

A Bunched Logic for Conditional Independence Jialu Bao Simon Docherty University of Wisconsin–Madison University College London Justin Hsu Alexandra Silva University of Wisconsin–Madison University College London Abstract—Independence and conditional independence are fun- For instance, criteria ensuring that algorithms do not discrim- damental concepts for reasoning about groups of random vari- inate based on sensitive characteristics (e.g., gender or race) ables in probabilistic programs. Verification methods for inde- can be formulated using conditional independence [8]. pendence are still nascent, and existing methods cannot handle conditional independence. We extend the logic of bunched impli- Aiming to prove independence in probabilistic programs, cations (BI) with a non-commutative conjunction and provide a Barthe et al. [9] recently introduced Probabilistic Separation model based on Markov kernels; conditional independence can be Logic (PSL) and applied it to formalize security for several directly captured as a logical formula in this model. Noting that well-known constructions from cryptography. The key ingre- Markov kernels are Kleisli arrows for the distribution monad, dient of PSL is a new model of the logic of bunched implica- we then introduce a second model based on the powerset monad and show how it can capture join dependency, a non-probabilistic tions (BI), in which separation is interpreted as probabilistic analogue of conditional independence from database theory. independence. While PSL enables formal reasoning about Finally, we develop a program logic for verifying conditional independence, it does not support conditional independence. independence in probabilistic programs. The core issue is that the model of BI underlying PSL provides no means to describe the distribution of one set of variables I. -

Week 2: Causal Inference

Week 2: Causal Inference Marcelo Coca Perraillon University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Health Services Research Methods I HSMP 7607 2020 These slides are part of a forthcoming book to be published by Cambridge University Press. For more information, go to perraillon.com/PLH. This material is copyrighted. Please see the entire copyright notice on the book's website. 1 Outline Correlation and causation Potential outcomes and counterfactuals Defining causal effects The fundamental problem of causal inference Solving the fundamental problem of causal inference: a) Randomization b) Statistical adjustment c) Other methods The ignorable treatment assignment assumption Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA) Assignment mechanism 2 Big picture We are going to review the basic framework for understanding causal inference This is a fairly new area of research, although some of the statistical methods have been used for over a century The \new" part is the development of a mathematical notation and framework to understand and define causal effects This new framework has many advantages over the traditional way of understanding causality. For me, the biggest advantage is that we can talk about causal effects without having to use a specific statistical model (design versus estimation) In econometrics, the usual way of understanding causal inference is linked to the linear model (OLS, \general" linear model) { the zero conditional mean assumption in Wooldridge: whether the additive error term in the linear model, i , is correlated with the -

Conditional Independence and Its Representations*

Kybernetika, Vol. 25:2, 33-44, 1989. TECHNICAL REPORT R-114-S CONDITIONAL INDEPENDENCE AND ITS REPRESENTATIONS* JUDEA PEARL, DAN GEIGER, THOMAS VERMA This paper summarizes recent investigations into the nature of informational dependencies and their representations. Axiomatic and graphical representations are presented which are both sound and complete for specialized types of independence statements. 1. INTRODUCTION A central requirement for managing reasoning systems is to articulate the condi tions under which one item of information is considered relevant to another, given what we already know, and to encode knowledge in structures that display these conditions vividly as the knowledge undergoes changes. Different formalisms give rise to different definitions of relevance. However, the essence of relevance can be captured by a structure common to all formalisms, which can be represented axio- matically or graphically. A powerful formalism for informational relevance is provided by probability theory, where the notion of relevance is identified with dependence or, more specifically, conditional independence. Definition. If X, Y, and Z are three disjoint subsets of variables in a distribution P, then X and Yare said to be conditionally independent given Z, denotedl(X, Z, Y)P, iff P(x, y j z) = P(x | z) P(y \ z) for all possible assignments X = x, Y = y and Z = z for which P(Z — z) > 0.1(X, Z, Y)P is called a (conditional independence) statement. A conditional independence statement a logically follows from a set E of such statements if a holds in every distribution that obeys I. In such case we also say that or is a valid consequence of I. -

Causality, Conditional Independence, and Graphical Separation in Settable Systems

ARTICLE Communicated by Terrence Sejnowski Causality, Conditional Independence, and Graphical Separation in Settable Systems Karim Chalak Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/neco/article-pdf/24/7/1611/1065694/neco_a_00295.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 [email protected] Department of Economics, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, U.S.A. Halbert White [email protected] Department of Economics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, U.S.A. We study the connections between causal relations and conditional in- dependence within the settable systems extension of the Pearl causal model (PCM). Our analysis clearly distinguishes between causal notions and probabilistic notions, and it does not formally rely on graphical representations. As a foundation, we provide definitions in terms of suit- able functional dependence for direct causality and for indirect and total causality via and exclusive of a set of variables. Based on these founda- tions, we provide causal and stochastic conditions formally characterizing conditional dependence among random vectors of interest in structural systems by stating and proving the conditional Reichenbach principle of common cause, obtaining the classical Reichenbach principle as a corol- lary. We apply the conditional Reichenbach principle to show that the useful tools of d-separation and D-separation can be employed to estab- lish conditional independence within suitably restricted settable systems analogous to Markovian PCMs. 1 Introduction This article studies the connections between -

The Hardness of Conditional Independence Testing and the Generalised Covariance Measure

The Hardness of Conditional Independence Testing and the Generalised Covariance Measure Rajen D. Shah∗ Jonas Peters† University of Cambridge, UK University of Copenhagen, Denmark [email protected] [email protected] March 24, 2021 Abstract It is a common saying that testing for conditional independence, i.e., testing whether whether two random vectors X and Y are independent, given Z, is a hard statistical problem if Z is a continuous random variable (or vector). In this paper, we prove that conditional independence is indeed a particularly difficult hypothesis to test for. Valid statistical tests are required to have a size that is smaller than a predefined significance level, and different tests usually have power against a different class of alternatives. We prove that a valid test for conditional independence does not have power against any alternative. Given the non-existence of a uniformly valid conditional independence test, we argue that tests must be designed so their suitability for a particular problem may be judged easily. To address this need, we propose in the case where X and Y are univariate to nonlinearly regress X on Z, and Y on Z and then compute a test statistic based on the sample covariance between the residuals, which we call the generalised covariance measure (GCM). We prove that validity of this form of test relies almost entirely on the weak requirement that the regression procedures are able to estimate the conditional means X given Z, and Y given Z, at a slow rate. We extend the methodology to handle settings where X and Y may be multivariate or even high-dimensional. -

STAT 535 Lecture 2 Independence and Conditional Independence C

STAT 535 Lecture 2 Independence and conditional independence c Marina Meil˘a [email protected] 1 Conditional probability, total probability, Bayes’ rule Definition of conditional distribution of A given B. PAB(a, b) PA|B(a|b) = PB(b) whenever PB(b) = 0 (and PA|B(a|b) undefined otherwise). Total probability formula. When A, B are events, and B¯ is the complement of B P (A) = P (A, B)+ P (A, B¯) = P (A|B)P (B)+ P (A|B¯)P (B¯) When A, B are random variables, the above gives the marginal distribution of A. PA(a) = X PAB(a, b) = X PA|B(a|b)PB(b) b∈Ω(B) b∈Ω(B) Bayes’ rule PAPB|A PA|B = PB The chain rule Any multivariate distribution over n variables X1,X2,...Xn can be decomposed as: PX1,X2,...Xn = PX1 PX2|X1 PX3|X1X2 PX4|X1X2X3 ...PXn|X1...Xn−1 1 2 Probabilistic independence A ⊥ B ⇐⇒ PAB = PA.PB We read A ⊥ B as “A independent of B”. An equivalent definition of independence is: A ⊥ B ⇐⇒ PA|B = PA The above notation are shorthand for for all a ∈ Ω(A), b ∈ Ω(B), PA|B(a|b) = PA(a) whenever PB =0 PAB(a, b) = PA(a) whenever PB =0 PB(b) PAB(a, b) = PA(a)PB(b) Intuitively, probabilistic independence means that knowing B does not bring any additional information about A (i.e. doesn’t change what we already be- lieve about A). Indeed, the mutual information1 of two independent variables is zero. -

Overview Examples Probability Review Probability Review Independence

Overview CS 287: Advanced Robotics Thus far: Fall 2009 Optimal control and reinforcement learning We always assumed we got to observe the state at each time and the challenge was to choose a good action Lecture 21: HMMs, Bayes filter, smoother, Kalman filters Current and next set of lectures The state is not observed Instead, we get some sensory information about the state Pieter Abbeel UC Berkeley EECS Challenge: compute a probability distribution over the state which accounts for the sensory information (“evidence”) which we have observed. Examples Probability review Helicopter For any random variables X, Y we have: A choice of state: position, orientation, velocity, angular rate Definition of conditional probability: Sensors: GPS : noisy estimate of position (sometimes also velocity) P(X=x | Y=y) = P(X=x, Y=y) / P(Y=y) Inertial sensing unit: noisy measurements from (i) 3-axis gyro [=angular rate sensor], (ii) 3-axis accelerometer [=measures acceleration + gravity; e.g., measures (0,0,0) in Chain rule: (follows directly from the above) free-fall], (iii) 3-axis magnetometer Mobile robot inside building P(X=x, Y=y) = P(X=x) P(Y=y | X=x ) A choice of state: position and heading = P(Y=y) P(X=x | Y=y) Sensors: Bayes rule: (really just a re-ordering of terms in the above) Odometry (=sensing motion of actuators): e.g., wheel encoders Laser range finder: measures time of flight of a laser beam between departure and return (return is typically happening when hitting a surface that reflects the beam back P(X=x | Y=y) = P(Y=y -

Contents 7 Conditioning

Probability for mathematicians DEPENDENCE TAU 2013 61 Contents 7 Conditioning 61 7a Whatistheproblem ....................... 61 7b Discretecase ........................... 63 7c Conditionalexpectation . 64 7d Aconvergencetheorem. 66 7e Conditionalmeasures. .. .. 66 7f Markov property as conditional independence . 74 7 Conditioning 7a What is the problem First, three results announced. They are rather trivial is such special cases as discrete distributions or absolutely continuous distributions, but nontrivial for singular (and mixed) distributions. We’ll see that the general theory holds for all distributions, and generalizes to high and even infinite dimension. 7a1 Proposition. Every 2-dimensional random variable (X,Y ) is distributed like f(U),g(U, V ) for some Lebesgue measurable functions f : (0, 1) → R and g : (0, 1) × (0,1) → R such that f is increasing on (0, 1), and g(u, ·) is increasing on (0, 1) for each u ∈ (0, 1); here U, V are independent random variables distributed uniformly on (0, 1). Such f is called the quantile function of X; and g(u, ·) is the conditional quantile function of Y given X = f(u). 7a2 Proposition. Let (X1,Y1) be a 2-dimensional random variable (on some probability space), and (Y2,Z2) another 2-dimensional random variable (on another probability space) such that Y1 and Y2 are identically distributed. Then there exists (on some probability space) a 3-dimensional random vari- able (X,Y,Z) such that (X,Y ) is distributed like (X1,Y1), and (Y,Z) is distributed like (Y2,Z2). The idea is simple: X and Z are conditionally independent given Y . But what exactly does it mean? 7a3 Theorem (disintegration of measure). -

Fast and Powerful Conditional Randomization Testing Via Distillation

Fast and Powerful Conditional Randomization Testing via Distillation Molei Liu∗1, Eugene Katsevich2, Lucas Janson3, and Aaditya Ramdas4 1Department of Biostatistics, Harvard Chan School of Public Health 2Statistics Department, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania 3Department of Statistics, Harvard University 4Departments of Statistics & Machine Learning, Carnegie Mellon University Abstract We consider the problem of conditional independence testing: given a response Y and co- variates (X; Z), we test the null hypothesis that Y ?? X j Z. The conditional randomization test (CRT) was recently proposed as a way to use distributional information about X j Z to exactly (non-asymptotically) control Type-I error using any test statistic in any dimensionality without assuming anything about Y j (X; Z). This flexibility in principle allows one to derive powerful test statistics from complex prediction algorithms while maintaining statistical validity. Yet the direct use of such advanced test statistics in the CRT is prohibitively computationally expensive, especially with multiple testing, due to the CRT's requirement to recompute the test statistic many times on resampled data. We propose the distilled CRT, a novel approach to using state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms in the CRT while drastically reducing the number of times those algorithms need to be run, thereby taking advantage of their power and the CRT's statistical guarantees without suffering the usual computational expense. In addition to distillation, we propose a number of other tricks like screening and recycling computations to further speed up the CRT without sacrificing its high power and exact validity. Indeed, we show in simulations that all our proposals combined lead to a test that has similar power to the most powerful existing CRT implementations but requires orders of magnitude less compu- tation, making it a practical tool even for large data sets.