A Comparison of the Utica Zoo, the Rosamond Gifford Zoo and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to Syracuse

WELCOME TO SYRACUSE As you begin your new journey in Syracuse, we have included some information that you may find helpful as you adjust to your new home. Inside you will find information about our city to jumpstart your Syracuse experience. CLIMATE & WEATHER SNAPSHOT OF SYRACUSE! Experience four distinct The city of Syracuse is located in Onondaga County seasons in the geographic center of New York State. The Average Temperatures: Onondaga, Syracuse Metropolitan Area is made up of Cayuga, Madison, Onondaga, and Oswego counties. Area Code: 315 Population in 2021: City of Syracuse: 141,491 Onondaga County: 458,286 Median Age: Syracuse: 30.6 September: Onondaga County: 39 64 degrees New York State: 38.2 United States: 38.2 The Heart of New York From Syracuse, it’s easy to venture Montreal Ottawa out to explore the state, as well CANADA Burlington January: as major eastern cities. VERMONT Toronto NEW YORK 24 degrees NEW Nearby Distance Rochester HAMPSHIRE Buffalo SYRACUSE Boston Major Cities by Miles Albany Binghamton MASSACHUSETTS Hartford Albany, NY 140 miles RHODE CONNECTICUT ISLAND Baltimore, MD 300 miles Cleveland PENNSYLVANIA OHIO Newark New York City Binghamton, NY 75 miles Pittsburgh Philadelphia Boston, MA 300 miles NEW JERSEY Buffalo, NY 150 miles WEST Baltimore VIRGINIA Chicago, IL 665 miles Washington, DC DELAWARE Cleveland, OH 330 miles VIRGINIA MARYLAND Montreal, QC 250 miles New York, NY 260 miles Niagara Falls, NY 165 miles Philadelphia, PA 255 miles #54 Best National Pittsburgh, PA 345 miles Universities Rochester, NY 85 miles ~ US News & World Report Toronto, ON 250 miles July: Washington, DC 350 miles 72 degrees TRANSPORTATION There are many options to navigate the city, even if you don’t have a car. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT Providing a level of excellence that makes the Rosamond Gifford Zoo a national leader in animal care, conservation and visitor experience. 1 A JOINT MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD TABLE OF CONTENTS Facebook followers increased from 61.3K at the start The year 2020 was undoubtedly the most challenging in our history. However, we can celebrate of 2020 to 65.8K on many successes which proved that perseverance, teamwork and, most importantly, a supportive December 31, 2020, adding community can see us through anything. Navigating a Pandemic 4 followers. Over the past year, our amazing Friends of the Zoo community truly went above and beyond for 4,500 Maintaining Partnerships your zoo. You let us know how much you missed visiting while we were closed, you came back 9 Surpassed as soon as you could, and you contributed to several campaigns to help the zoo recover from the 10 Engaging our Community pandemic. 25,000 Capital Improvements followers on Instagram, When we substituted a fundraising campaign - $50K for 50 Years – for a Friends of the Zoo 50th 12 a huge milestone. anniversary celebration, you pitched in to help us raise more than $20,000 over our $50,000 goal. When we offered a two-month extension on memberships to cover the COVID closure, most 13 2020 Accomplishments of you donated it back to the zoo. When we asked our volunteers to help the zoo acquire more flamingos to expand our flock, you donated to the Fund for Flamingo Flamboyance. Or, you gave 14 Development and Fundraising to our Annual Appeal on behalf of a baby patas monkey named Iniko -- “born during troubled Nearly 9,140 times.” 15 New Leadership children and adults actively participated in conservation education learning programs When, at the end of an already difficult year, we lost our two youngest elephants to another 16 Future Focus deadly virus, you mourned with us, sent messages of encouragement and donated to the Ajay and Batu Memorial Fund to help the new Animal Health Center test for and treat EEHV. -

City of Syracuse Consolidated Plan Year 30 2004-2005

Mayor Matthew J. Driscoll City of Syracuse Consolidated Plan Year 30 2004-2005 Prepared by the Department of Community Development 201 E. Washington Street, Room 612 Syracuse, New York 13202 April 2004 Consolidated Plan 2004-2005 Public Comments Consolidated Plan 2004-2005 Public Hearing March 29, 2004 Consolidated Plan 2004-2005 Newspaper Articles Draft Consolidated Plan 2004-2005 Announcement of Availability Draft Consolidated Plan 2004-2005 Public Meeting March 10, 2004 Community Needs Meeting October 23, 2003 Request for Proposals September 2003 Table of Contents 2004-2005 (Year 30) Consolidated Plan Page No. Executive Summary 1 Section 1 Introduction 10 Purpose 11 Key Participants 13 Citizen Participation 18 Community Profile 35 Section 2 Housing Market Analysis 41 Housing Market Study 42 Syracuse Housing Authority 45 Assisted Housing 55 Continuum of Care Strategy 61 Barriers to Affordable Housing 76 Fair Housing Initiatives 79 Section 3 Housing and Homeless Needs Assessment 90 Housing Needs 91 Housing Needs Assessment 92 Homeless Population Needs 99 Special Needs Population 106 Section 4 Economic Development 112 Section 5 Historic Preservation 124 Collaborative Preservation Efforts 125 Historic Preservation: 290 E. Onondaga Street 126 Section 6 Strategic Plan 140 Housing Strategic Plan 141 Homeless Strategic Plan 146 Community Development Strategic Plan 147 Public Facilities 148 Planning & Administration 149 Infrastructure 150 Public Services 151 Economic Development 152 Barriers to Affordable Housing 156 Lead-Based Paint Hazards -

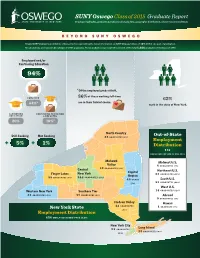

SUNY Oswego Class of 2015 Graduate Report Employer Highlights, Graduate & Professional Study Data, Geographic Distribution, Alumni Recommendations

SUNY Oswego Class of 2015 Graduate Report Employer highlights, graduate & professional study data, geographic distribution, alumni recommendations BEYOND SUNY OSWEGO Beyond SUNY Oswego is an initiative of Career Services providing the latest information on SUNY Oswego’s Class of 2015 within one year of graduation. All calculations are based on knowledge of 1,057 graduates. These graduates represent 65% percent of the total 1,626 graduates of the Class of 2015. Employed and/or Continuing Education 94% *Of the employed grads at left, of those working full-time EMPLOYED 86% 62% are in their field of choice. 64%* work in the state of New York. CONTINUING CONTINUING EDUCATION EDUCATION & EMPLOYED 20% 10%* North Country Still Seeking Not Seeking 28 GRADUATES (4%) Out-of-State Employment + 5% + 1% Distribution 116 EMPLOYED OUTSIDE OF NYS (11%) Mohawk Midwest U.S. Valley 8 GRADUATES (7%) Central 28 GRADUATES (4%) Capital Northeast U.S. Finger Lakes New York GRADUATES (28%) Region 33 58 GRADUATES (9%) 243 G R ADUATE S (37%) 45 GRADS South U.S. GRADUATES (44%) (7%) 51 West U.S. Western New York Southern Tier 14 GRADUATES (12%) 23 GRADUATES (3%) 37 GRADUATES (6%) Abroad 9 GRADUATES (8%) Hudson Valley Hawaii 43 GRADUATES 1 GRADUATE (1%) New York State (7%) Employment Distribution 658 EMPLOYED IN NEW YORK STATE New York City Long Island 98 GRADUATES 55 GRADUATES (8%) (15%) 678 Graduates • Information on 424 (62.5%) Top Advice College of Liberal Arts 232 Employed (54.7%) • 115 Graduate School (27.1%) from the and Sciences 38 Employed & Graduate School -

Sleep Inn & Suites Airport East Syracuse, NY 13057

Sleep Inn & Suites Airport East Syracuse, NY 13057 A family developed, owned and operated hotel since 2016. GREGG SARGENT | DIRECTOR 631-553-2917 [email protected] This listing is property of Baron Realty Group and is only intended for the current recipient. If you received this listing through an unauthorized representative, please disregard. Baron Realty Group has been chosen to exclusively market for sale the Sleep Inn & Suites located at 6344 E Molloy Road in East Syracuse conveniently located off NYS Thruway 90, US 81 and Route 481. This 3 story elevator building with 54 spacious rooms and suites was newly developed two years ago. This full service hotel property is one mile from the Syracuse Hancock International Airport and only minutes from downtown Syracuse, the Carrier Dome and Syracuse University. This is a true turn-key opportunity to acquire a new hospitality asset and established business in a stable New York market. The hotel contains two kitchens, a restaurant with a full bar and boasts 4 banquet rooms for business meetings, weddings and corporate events of all sizes. The large courtyard located just outside the bar is equipped with natural gas fire pits and heat lamps providing a great outdoor space to accommodate guests year around. 6344 E Molloy Road East Syracuse, New York 13057 Purchase Price $7,900,000 Property Improvement Plan $0 Total Investment $7,900,000 Total Number of Rooms 54 Occupancy 67.3% Year Built 2016 Number of Stories 3 Type of Ownership Fee Simple Financial data provided upon execution of CA from Baron Realty Group LLC. -

City of Syracuse Consolidated Plan 5 Annual Action Plan 2009-2010

Mayor Matthew J. Driscoll City of Syracuse Consolidated Plan 5th Annual Action Plan 2009-2010 Fernando Ortiz, Jr., Commissioner Department of Community Development 201 E. Washington Street, Room 612 Syracuse, New York 13202 May 2009 SF 424 The SF 424 is part of the CPMP Annual Action Plan. SF 424 form fields are included in this document. Grantee information is linked from the 1CPMP.xls document of the CPMP tool. SF 424 Complete the fillable fields (blue cells) in the table below. The other items are pre-filled with values from the Grantee Information Worksheet. 03/19/2009 Applicant Identifier Type of Submission Date Received by state State Identifier Application Pre-application Date Received by HUD Federal Identifier Construction Construction Non Construction Non Construction Applicant Information City of Syracuse NY366376 SYRACUSE Department of Community Development Organizational DUNS 07-160-7675 201 E Washington St, Room 612 Organizational Unit Syracuse New York Department 13202 Country U.S.A. Division Employer Identification Number (EIN): Onondaga County 15-60000416 Program Year Start Date (MM/DD) Applicant Type: Specify Other Type if necessary: Local Government: City Specify Other Type U.S. Department of Program Funding Housing and Urban Development Catalogue of Federal Domestic Assistance Numbers; Descriptive Title of Applicant Project(s); Areas Affected by Project(s) (cities, Counties, localities etc.); Estimated Funding Community Development Block Grant 14.218 Entitlement Grant CDBG Project Titles Description of Areas Affected -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT a National Leader in Animal Care, Conservation and Visitor Experience

Providing a level of excellence that makes the Rosamond Gifford Zoo 2019 ANNUAL REPORT a national leader in animal care, conservation and visitor experience. 1 A JOINT MESSAGE FROM THE INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD There is much to celebrate in the Friends 2019 annual report. Last year saw the birth of a baby Asian elephant and two critically endangered Amur leopard cubs. The zoo unveiled several new exhibits and welcomed several new rare and endangered species. Friends of the Zoo and our county partners upgraded and expanded the Helga Beck Asian Elephant Preserve, and construction began on a key Friends project, the Zalie & Bob Linn Amur Leopard Woodland. Some 332,000 people visited the zoo, enhanced by the Friends’ addition of a summer-long Big Bugs! attraction and a new 18-horse carousel. Our education programs involved more than 10,000 participants, including more than 7,500 school-age children. Our volunteers provided educational enrichment to guests, beautified the zoo with lush gardens and joined work projects to improve the facility. Our catering staff executed more than 120 events, from weddings to the Snow Leopard Soirée to Brew at the Zoo. All told, Friends provided more than $175,000 in direct support to the zoo and allocated more than $500,000 for capital improvements to help the zoo meet the “gold standard” for animal care and welfare, conservation education and saving species. We are extremely proud of these accomplishments, and we hope you will enjoy this look back at our achievements and all the people, businesses and community partners that helped make them possible. -

Connect-Card-Directory.Pdf

Connect Card directory One great card can connect you to: • WCNY Event ticket discounts. • Restaurants and attractions 2-for-1 dining, admissions discounts, or special benefits. CONNECT CARD BENEFITS BY LEVEL • Bronze Level Discounts on WCNY events including live screenings, concerts, dining, and attractions. • Silver, Gold, and Platinum Levels Bronze benefits plus special invitations to WCNY events. CONNECT CARD FAQs How to find the most current list of restaurants & attractions? New partners are added regularly. For complete descriptions, sample menus, photos and other information, Visit wcny.org/connectcard or use the Connect Card App on your smart phone. How to use Connect Card? Simply present your Connect Card to your server when paying your bill or ticket agent when purchasing admission. The associated code number on the back of your card will be checked off, confirming that you have received your benefit. Search “WCNY Connect Card” App on your smartphone and a create a profile. Redeem using the App: 1. Log into account 2. Find provider page and check the benefits, restrictions and other details 3. Hit the Redeem button 4. Show the redeem code to server or ticket agent 5. You will receive the redemption information through email *Please check the restaurant/attraction profiles to understand any restrictions that may be applied when using your Connect Card. Unless otherwise stated, benefits are single use only. When redeeming 2-for-1 benefits, the lower cost item will be removed from your bill. Additional restrictions may apply, so please read the benefits offer before purchasing. 2 Connect Card 5 Zones Includes Southern Canada 2 1 6 4 Includes 7 Long Island 3 8 Includes All Other Areas For the most updated list of Connect Card partners, visit wcny.org/connectcard or download the app on your Apple or Android device. -

Checkbook August 19, 2016

Pay Date Fund Department No. Department Title Voucher ID Vendor No. Vendor Name Payment Amount Check No. 8/19/2016 40021 6500000000 Onondaga County Public Library 03052510 0000019244 1ST POINT LLC 3,480.00 0000191406 8/19/2016 10001 0512000000 Construction & Office Planning 03052658 0000019244 1ST POINT LLC 3,400.00 0000191406 8/19/2016 20035 6550000000 Ocpl - Library Grants 03052651 0000019244 1ST POINT LLC 6,320.00 0000191406 8/19/2016 40021 6500000000 Onondaga County Public Library 03052511 0000019244 1ST POINT LLC 3,480.00 0000191406 8/19/2016 10030 7320030000 Criminal Court Supervisions 03052709 0000019000 3M ELECTRONIC MONITORING INC 1,320.00 0000191407 8/19/2016 10001 8110080000 Child Support/Title Iv-D F8 03052759 0000009699 ABC LEGAL SERVICES INC 80.00 0000191408 8/19/2016 10030 4395700000 MCH/Healthy Families Grants 03052455 0000007321 ABM JANITORIAL SERVICES NORTHEAST INC 529.83 0000191409 8/19/2016 10030 4395700000 MCH/Healthy Families Grants 03052451 0000007321 ABM JANITORIAL SERVICES NORTHEAST INC 1,242.40 0000191409 8/19/2016 10001 4350400300 Vector Control 03052452 0000007321 ABM JANITORIAL SERVICES NORTHEAST INC 165.29 0000191409 8/19/2016 10001 7920100000 Police Administration 03052698 0000009816 ABY MANUFACTURING GROUP INC 393.50 0000191410 8/19/2016 10001 8260301000 Adult Mental Health OMH Contra 03052688 0000005699 ACCESSCNY INC 574,369.00 0000191411 8/19/2016 10001 8260301000 Adult Mental Health OMH Contra 03052685 0000005699 ACCESSCNY INC 574,369.00 0000191411 8/19/2016 10001 8330103000 Child Welfare Services F62 -

Consolidated Report of the Transition Team Task Forces On: • Economic Development • Government Modernization • Community R

Consolidated Report of the Transition Team Task Forces on: Economic Development Government Modernization Community Revitalization Social Services/Education Workforce Relations Intergovernmental Relations Presented to the Onondaga County Executive-Elect Joanne M. Mahoney on December 20th & 21st, 2007. Joanne M. Mahoney Edward Kochian County Executive County of Onondaga Deputy County Executive Office of the County Executive John H. MuIroy Civic Center, 14th Floor 421 Montgomery Street, Syracuse, New York 13202 Phone: 315 435 3516 Fax: 315 435.8582 ongov.net January 25, 2008 My Fellow Onondaga County Residents: The transition into the Office of the County Executive has been extraordinary. The people I have spoken with have offered support and ideas and I am very intent on implementing an agenda that provides opportunity for all our residents. In preparation for starting my term as County Executive, we formed six task forces comprised of a diverse group of citizens who care deeply about our future. The six groups were: Economic Development, Government Modernization, Community Revitalization, Social Services/Education, Workforce Relations, and Intergovernmental Relations. Each group was tasked with developing specific ideas for implementing and strengthening the Opportunity Agenda that was introduced during the campaign. The results of their efforts are compiled in this report. You will be impressed with the level of work accomplished in a six-week timeframe. The task force members dedicated themselves to the process and succeeded in achieving their goals. There are numerous ideas - some big, some small - that can be integral in improving Onondaga County. There are many issues facing our County. As we move forward with implementing the Opportunity Agenda, ideas put forth by each task force group will be a key part of determining what path we take. -

Asian Elephant Extravaganza & Siri's 50Th Birthday Celebration to Be

Asian Elephant Extravaganza & Siri’s 50th Birthday Celebration to be held Saturday, August 19 at Rosamond Gifford Zoo The Rosamond Gifford Zoo will hold its annual Asian Elephant Extravaganza on Saturday, August 19. This daylong event celebrates Asian elephants, the cultures of their native countries and – this year -- elephant matriarch Siri’s 50th birthday. The event is free with zoo admission. The yearly event at the zoo is co-sponsored by CNY Arts and features performances from the cultures of Asia and India, through Syracuse University’s South Asia Center and the Southeast Asia Program at Cornell University. The event includes classical Indian dance, Indonesian gamelan music and a ceremonial fact-painting of Siri. The zoo is using the occasion to mark the milestone birthday of Siri, the oldest animal at the zoo. The zoo proclaimed this summer the “Summer of Siri” and launched a fundraiser, Pennies for Pachyderms, to raise money for wild elephant conservation in her honor. “So many people in our community have grown up knowing Siri and see her as an important ambassador of the zoo,” said Zoo Director Ted Fox. “Over the years, many of the improvements we have made to the zoo have developed with Siri in mind. We expect a huge turnout of Siri fans at her 50th birthday party.” When Siri came to the zoo as a 5-year-old in 1972, she was the zoo’s only elephant. Her need for a bigger enclosure was one of the reasons that led the zoo to close and undergo a complete renovation in the 1980s. -

Urban Fellowship Apply Your Passion for Urban Education

SYRACUSE URBAN FELLOWSHIP APPLY YOUR PASSION FOR URBAN EDUCATION SYRACUSE CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT & SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY ALL IN. JOIN SYRACUSE CITY SCHOOLS FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM SYRACUSE CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT & SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY In exchange for a 5-year commitment to teach in the Syracuse City School District: Full tuition toward a Master’s Degree Assistance with New York State in Education at Syracuse University Teacher Certification Process for those who possess comparable Starting salary of $47,500 teacher certification in a another » Additional pay for prior experience state » Opportunity to earn additional » Includes stipend to assist with $5,000-$8,900 by working in expense extended learning time school FELLOWSHIP REQUIREMENTS GRADUATE PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS CERTIFICATION Must possess or be eligible 1. 3.0 Undergraduate GPA for NYS teacher certification or possess comparable 2. Three Letters of teacher certification from Recommendation another state 3. Personal statement regarding career RESIDENCE aspirations Must reside in the city of Syracuse (generous moving 4. Resume allowance of $1,500 and 5. Unofficial Transcripts non-financial housing support included) APPLY TODAY To apply please visit our website at www.joinsyracusecityschools.com and complete an application. Any questions about the program or the application process should be directed to Scott Persampieri, Director of Recruitment at [email protected]. The Syracuse City School District is looking to ensure that our faculty better represents the diversity of our student body. We are looking for graduates in the teaching areas of: Mathematics, Science, English as a New Language (ENL), Library Media, Special Education, and Technology Education. WE’RE ALL IN. ARE YOU? SYRACUSE CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT AT A GLANCE The Syracuse City School District We’re helping teachers reach their full (SCSD) educates more than 21,000 potential through richer feedback, students each day, from pre- new opportunities to develop and kindergarten through 12th grade.