The Principles and Techniques of Defence in Rugby Union by Paul Westgate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fo Us Spring 2016

Fo us Spring 2016 A C A D E M Y Contents 2 A Message from the 13 Out and about Principal 15 Lifestyle Company 3 Sixth Form 16 In the Spotlight: Ché Donaldson- 4 JETs Update Brook 5 Sponsor’s Dinner 17 Charity Days 6 Mock Trial Competition 20 Staff Photo Competition 7 Arts Company 21 Sport Sideline 8 In the Spotlight: Sophie Bayliss 23 Discovery Company 9 Head Start 24 In the Spotlight: Ryan Morris Kickstart 25 Science 10 Q3 Community ACF Update 27 Social Design Company 11 Communications Company 28 In the Spotlight: Kiera Thaper 12 In the Spotlight: Jack Reeves 29 Music Department Design & Cover Photos: Miss Jess Clay Front Cover: Spring has sprung in Q3’s greenhouse! A Message from the Principal 3 Academy is Our new Vice Principal/ Qa vibrant and Head of School, Mr exciting place to be Arnull has settled into and I hope you can the Q3 family. He brings feel the energy as a wealth of experience you read the latest and will begin to take on edition of FoQus. more of the day to day operation of Q3 Great As we reflect on the Barr as I start to work many successes across both academies. we also remember Grace Payne who sadly passed away at the end of last term. Grace Q3 Langley will open in September 2016 and was an inspirational lady, giving generously Mr Lee will take on the role of Head of School of her time, and her at Langley. contribution cannot be underestimated, indeed This term also sees the launch of our Pillars the very name Q3 was of Excellence which will further reinforce our her idea. -

Independent , 1997, Ireland, English

I f dictator? Fran Abrams ogised for using excessive force. Political Correspondent Campaigners against the arms trade have repeatedly claimed that Close encounter A woman hi Cathedral dose, SaHsbury, eyes Running Man, a bronze statue by the late sculptor Elisabeth Frink, one ola collection of her works In the Salisbury The Government’s ethical foreign Hawk jets have been used to attack Festival. Before Frink died In 1983, one of her final requests was that an open-air retrospective exhibition of her work be staged hi a public area after her death. Photograph: John Voos policy will not prevent ongoing sales civilians in occupied East Timor- re- of armoured vehicles and water ports which have been strongly de- cannon to Indonesia. The Indepen- nied. Officials have hinted that the dent has learnL manufacturer, British Aerospace Yet yesterday in a Parliamentary might be well advised not to apply written answer, Robin Cook, the for an export licence for the jets Fatherwins appeal to halt abortion Foreign Secretary, said: “We have until ministers have decided what made a firm commitment not to per: line to take on the sale. mil the sale of arms to regimes that It is believed that while Foreign Patricia Wynn Davies court she could not reveal the rea- stop the abortion and give him cus- where the House of Lords has re- born child’s “right" to life. An in- might use them for internal repres- Office ministers might hope to pre- Legal Affairs Editor sons because It would break her tody ofthe unborn baby and the cou- solved the issue in favour ofwomen terpretation in favour of fathers sion or international aggression.” vent new exports of Hawks to In- client’s confidentiality. -

SPECIALIST SPORTS – RUGBY an Explanation of Fees: There Are a Number of Factors That Influence the Fees Speakers Charge. These

– RUGBY SPECIALIST SPORTS An explanation of fees: There are a number of factors that influence the fees speakers charge. These include location, date and nature of the event. It ‘ ’ is therefore impossible to quote a one size fits all fee per speaker. The fee bands are therefore there to provide a rough guide but please enquire for specific quotes, as speakers are usually negotiable. Certain speakers may require hotel accommodation in addition to the fee and VAT will be applicable in some cases but this will be advised upon enquiry. Those marked in bold are our personal favourites in the office All speakers are Rugby Union unless denoted with (L) for Rugby League. £500•£1250 David Trick Harry Ellis Jeff Probyn Paul Wood (L) Des Drummond (L) Graham Price Gregor Townsend Nigel Redman Tim Stimpson Mike Lewis Leon Lloyd Brian Noble (L) Henry Paul (L/U) George Chuter Tommy Martyn (L) Sean Long (L) ’ Terry O Connor (L) Barrie McDermott (L) Robbie Paul (L) Craig Sandercock (L) Shaun Wane (L) Keith Senior (L) Paul Sculthorpe (L) Iestyn Harris (L/U) Neil Holding (L) Alex Murphy (L) Mike Foreshaw (L) Eorl Crabtree (L) John Stankovitch (L) Karl Kirkpatrick (L/U) Steve Ganson (L) Adrian Morley (L) Ray Fench (L) Garry Schofield OBE (L) Jamie Peacock (L) Phil Larder (L/U) Roy Dickinson (L) Lee Briers (L) Jim Mills (L) Jon Wilkin (L) Stuart Fielden (L) Andy Gregory (L) Bobbie Goulding (L) Rob Burrow (L) Paul Wellens (L) Jamie Jones Buchanan (L) Leon Pryce (L) Jimmy Gittins (L) Geoff Parling Garin Jenkins Craig Newby Gary Rees £1250•£3000 Kelly Brown John Bentley Gareth Chilcott Andy Gomersal Ian Robertson John Beattie Mark Regan Dean Richards JPR Williams Bill Beaumont Phil Bennett David Duckham Willie J. -

|O Monday 26Th May 1997 KO

|oMonday 26th May 1997 K.O. 6pm C L U B I N F O R M AT l i N OLDHAM ■■ FC Bear House, 52 Union Street, Oldham OLI IDJ 0161 624 4865 (3 lines) General Office 0891 44 00 70 Bears Hotline 0161 624 9615 Shop Line’ RUGBY LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP WINNERS 1909-10, 1910-11,1956-57 Runners Up C L U B D I R E C T O R Y 1906-07,1907-08,1908-09,1921-22,1954-55 FIRST DIVISION CHAMPIONS Chairman 1904-05 JAMES QUINN L A N C A S H I R E L E A G U E C H A M P I O N S Directors 1897-98, 1900-01, 1907-08, 1909-10, 1921-22, 1956-57, JOHN CHADWICK 1957-58 ROGER NORRIS RUGBY LEAGUE CHALLENGE CUP WINNERS M I K E W I N T E R B O T T O M 1899, 1925, 1927 Runners Up 1907, 1912, 1924, 1926 LANCASHIRE CUP WINNERS T O M P A T T E R S O N 1907, 1910, 1913, 1919, 1924, 1933, 1956, 1957, 1958 Executive Management Runners Up 1908, 1911, 1918, 1921, 1954, 1966, 1968, Chief Executive 1986, 1989 SECOND DIVISION CHAMPIONS JAMES QUINN 1963-64, 1981-82, 1987-88 Chief Secretary SECOND DIVISION PREMIERSHIP WINNERS KAREN SCOTT 1988, 1990 Runners Up, 1992 Media Maiiffiting Manager A B E K E R R RECORD VICTORY Commercial Manager 63-0 VGoole, March 18th 1899 (Challenge Cup Rd I) TBA 67-6 VLiverpool City, April 4th 1959 (League) RECORD SCORE S e n i o r A c c o u n t a n t 70-10 VBramley, Feb 12th 1995 (Challenge Cup Rd 4) PAUL TRAFFORD 67-6 VLiverpool City, April 4th 1959 (League) Dental Surgeon RECORD ATTENDANCE MR N. -

SPECIALIST SPORTS – RUGBY an Explanation of Fees: There Are A

– RUGBY SPECIALIST SPORTS An explanation of fees: There are a number of factors that influence the fees speakers charge. These include location, date and nature of the event. It ‘ ’ is therefore impossible to quote a one size fits all fee per speaker. The fee bands are therefore there to provide a rough guide but please enquire for specific quotes, as speakers are usually negotiable. Certain speakers may require hotel accommodation in addition to the fee and VAT will be applicable in some cases but this will be advised upon enquiry. Those marked in bold are our personal favourites in the office All speakers are Rugby Union unless denoted with (L) for Rugby League. £500•£1250 David Trick Harry Ellis Jeff Probyn Paul Wood (L) Des Drummond (L) Graham Price Gregor Townsend Nigel Redman Tim Stimpson Mike Lewis Leon Lloyd Brian Noble (L) Henry Paul (L/U) George Chuter Tommy Martyn (L) Sean Long (L) ’ Terry O Connor (L) Barrie McDermott (L) Robbie Paul (L) Craig Sandercock (L) Shaun Wane (L) Keith Senior (L) Paul Sculthorpe (L) Iestyn Harris (L/U) Neil Holding (L) Alex Murphy (L) Mike Foreshaw (L) Eorl Crabtree (L) John Stankovitch (L) Karl Kirkpatrick (L/U) Steve Ganson (L) Adrian Morley (L) Ray Fench (L) Garry Schofield OBE (L) Jamie Peacock (L) Phil Larder (L/U) Roy Dickinson (L) Lee Briers (L) Jim Mills (L) Jon Wilkin (L) Stuart Fielden (L) Andy Gregory (L) Bobbie Goulding (L) Nick Fozzard (L) Paul Wellens (L) Jamie Jones Buchanan (L) Leon Pryce (L) Jimmy Gittins (L) Geoff Parling Garin Jenkins Craig Newby Gary Rees £1250•£3000 Kelly Brown John Bentley Gareth Chilcott Andy Gomersal Ian Robertson John Beattie Mark Regan Dean Richards JPR Williams Bill Beaumont Phil Bennett David Duckham Willie J. -

I I L Fl F Fl U

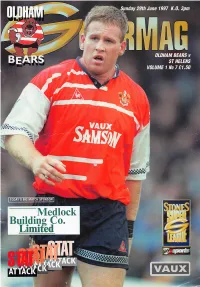

Sunday 29th June 1997 K.O. 3pm iilflfflU ■-la OLDHAM BEARS v ST HELENS V O L U M E 1 N o 7 £ 1 . 5 0 VAUX Vm Bear House, 52 Union Street, Oldham OLI IDJ 0161 624 4865 (3 lines) General Office 0891 44 00 70 Bears Hotline 0161 624 9615 Shop Line RUGBY LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP WINNERS 1909-10, 1910-11,1956-57 Runners Up C L U B D I R E C T O R Y 1906-07, 1907-08, 1908-09, 1921-22, 1954-55 FIRST DIVISION CHAMPIONS Chairman 1904-05 JAMES QUINN L A N C A S H I R E L E A G U E C H A M P I O N S Directors 1897-98, 1900-01, 1907-08, 1909-10, 1921-22, 1956-57, JOHN CHADWICK 1957-58 ROGER NORRIS RUGBY LEAGUE CHALLENGE CUP WINNERS M I K E W I N T E R B O T T O M 1899, 1925, 1927 Runners Up 1907, 1912, 1924, 1926 LANCASHIRE CUP WINNERS T O M P A T T E R S O N 1907, 1910, 1913, 1919, 1924, 1933, 1956, 1957, 1958 Executive Management Runners Up 1908, 1911, 1918, 1921, 1954, 1966, 1968, Chief Executive 1986, 1989 SECOND DIVISION CHAMPIONS JAMES QUINN 1963-64, 1981-82, 1987-88 Club Secretary SECOND DIVISION PREMIERSHIP WINNERS KAREN SCOTT 1988, 1990 Runners Up, 1992 Media Marketing Manager A B E K E R R ^ - — R E C O R D V I C T O R Y Acting Commercial Manager 63-0 VGoole, March 18th 1899 (Challenge Cup Rd I) JACQUI CLAYTON 67-6 VLiverpool City, April 4th 1959 (League) S e n i o r A c c o u n t a n t RECORD SCORE PAUL TRAFFORD 70-10 VBramley, Feb 12th 1995 (Challenge Cup Rd 4) 67-6 VLiverpool City, April 4th 1959 (League) Dental Surgeon RECORD ATTENDANCE MR N. -

University of Wales

<i3 . -7 07 l'4oo0tôo il uc 1 0326083 e- /\V ilililililililIIilililililililililtil o The 'Convergence of the Twain': A notational analysis of northern hemisphere rugby league and rugby union football (1988-2002) Simon John Eaves BA, PGCE, MSc. Submitted April 2006 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wales Director of Studies: Professor Mike Hughes (U\ilIC) Supervisors: Dr Kevin Lamb (University of Chester); Professor Roger Bartlett (University of Otago) DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed. ...(candidate) Date. lLo This thesis is the result of my own investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by reference in text. Signed ..(candidate) Date. tut, Loo I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for inter-library loan or photocopying (subject to the law of copyright), and for the title arid summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed.... ....(candidate) Date À9-a.t 2.Ð*b CONTENTS List of tables List of figures lv Aclarowledgements tx Abstract The'Convergence of the Tlvain': A notational analysis of rugby x league and rugby union football (1988 - 2002) Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Review of Literature 10 Chapter 3 Methods 49 Chapter 4 Reliability and normative profiles 7S Chaptcr 5 G¡me profiles 103 Chapter 6 Performance indicators 206 Chapter 7 Summary and conclusions 257 References 275 LIST OF TABLE,S Page Chapter 2 Review -

Big Match E'lijf^Tni'hwi B'iii F

Big Match E'lijf^Tni'hwi B'iii f Sheffield Eagles at Large 824 Attercliffe Road jyiaying Bradford at Odsal is Our ball control this season has Sheffield S9 3RS .1 no easy task. Remember: been quite good: we always aim Tel: 0114 261 0326 they put more that 50 points for a75% success rate. Against Fax: 0114 261 0303 against St. Helens and Wigan, Warrington and Castleford we President & so going there without were able to force the Chief Executive: Nick Pinkney, Keith Senior, percentage into the mid 80's by making less than ten errors. Teriy Sharman Johnny Lawless, Paul Carr, Martin Wood and with At Odsal the opposite happenec Directors: Bright Sodje, Darren Turner, and in our first set Jean Marc Richard Pepper Dale Laughton and Matt Crowther also injured, Garcia’s forward to Peter Sephton Whetu Taewa, on the second Kathie Sharman we were always going to be up against it. Mark Aston gave aforward pass Teriy Sharman to Paul Broadbent and then the We realised that to get aresult mistakes spread throughout the Company Secretary: team like arash. We made 11 Kathie Sharman our tactics must be carefully though out and rigidly adhered errors in the first half total of 18 to. we all agreed that ball possession periods and a Office Manager: staggering 14 errors in 22 in the Julie Bush security was the key, particularly since the Bulls have been second half. involved in an energy-sapping Marketing & Those 25 errors in 40 plays Media Manager fixture against Halifax the previous Wednesday. means that we simply Mike Turner committed suicide -ahard Rugby Football League is lesson to learn, one which Iam Commercial Manager: unique in that the team is sure has now sunk in. -

Rugby Union 2000 For

1 THE ROYAL MARINES Rugby League 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO RUGBY LEAGUE 3 Student Notes Teacher Notes INTRODUCTION TO THE MODULE 3 SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SHEET 4 KEY TO THE DIAGRAMS UNIT 1 SCHEME OF WORK 5 UNIT 2 THE SKILLS OF THE GAME 8 AHB AHB ACTING HALF-BACK PLAYER LESSON 1 CATCHING AND PASSING 8 FB BC BALL CARRIER LESSON 2 LINE PASSING 9 PLAYER RUNNING WITH BALL SH SCRUM-HALF LESSONS 3 AND 4 TACKLING 10 LESSON 5 PLAY THE BALL 13 PLAYER RUNNING WITHOUT BALL SO STAND-OFF LESSON 6 MOVING THE BALL WIDE 14 PLAYER PASSING BALL FR FIRST RECEIVER LESSON 7 KICKING AND REGAINING POSSESSION 15 PLAYER KICKING BALL SR SECOND RECEIVER LESSON 8 TWO AGAINST ONE 17 CONES TR THIRD RECEIVER LESSON 9 THE DEFENSIVE LINE 18 INNER TUBE C CENTRE LESSON 10 PLOYS FROM ACTING HAIF-BACK 21 LESSON 11 MARKER DEFENCE 21 SHIELD W WING LESSON 12 SUPPORT PLAY 22 COACH FR FULL-BACK LESSON 13 THE SCRUMMAGE 24 DEFENCE M MARKER LESSON 14 PICKING UP A ROLLING BALL 27 OFFENCE R RUNNER UNIT 3 THE GAME 28 S SUPPORT UNIT 4 PHYSICAL CONDITIONING 30 Prepared for The Royal Navy in association with The Rugby Football UNIT 5 MENTAL PREPARATION 34 League and produced by Education and Youth Limited, London. UNIT 6 INJURY PREVENTION 35 If there is any support you feel The Royal Navy can give regarding this UNIT 7 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 36 project please contact 0870 333 0423. UNIT 8 CURRENT ISSUES 36 Acknowledgements UNIT 9 AWARD SCHEMES 39 These notes have been compiled by Phil Larder Director of Coaching with the assistance of: John Bartlett, Geoff Clare, Tony Tucker and RECOMMENDED READING 40 Martin Tunnacliffe, all of who head school physical education CONTACT NUMBERS 40 departments and who have a wealth of knowledge on GCSE physical education. -

LEIGH CENTURIONS V FEATHERSTONE ROVERS FRIDAY, 8Th August 2014 at LEIGH SPORTS VILLAGE • KICK OFF 8.00PM

aa LEIGH v FEATHERSTONE 40pp_Layout 1 05/08/2014 16:24 Page 1 KINGSTONE PRESS CHAMPIONSHIP ROUND 23 LEIGH CENTURIONS v FEATHERSTONE ROVERS FRIDAY, 8th August 2014 AT LEIGH SPORTS VILLAGE • KICK OFF 8.00PM Match Sponsor Match Ball Sponsor Programme Sponsor ISSUE 13 PRICE £2.50 aa LEIGH v FEATHERSTONE 40pp_Layout 1 05/08/2014 16:24 Page 2 HONOURS Championship Winners: 1905-06 Division One Champions: 1981-82 Division Two Champions: 1977-78, 1985-86, 1988-89 Cover Star: Tom Armstrong Challenge Cup Winners: looks to evade 1920-21, 1970-71 Brendan Rawlins Lancashire Cup Winners: 1952-53, 1955-56, 1970-71, 1981-82 BBC2 Floodlit Trophy: WHO’S WHO 1969-70, 1972-73 At Leigh Centurions Promotion To Top Division achieved(Not as Champions): Hon Life President Kit men 1963-64, 1975-76, 1991-92 Mr Tommy Sale MBE Mr Frank Taylor Other Promotion season: Hon Vice President Mr Sean Fairhurst 1997 (Division 3 to Division 2) Mr Tommy Mather Mr Andy Burnham MP Northern Ford Minor Premiership Hon Life Members Under 20’s Coach Winners: 2001 Mr Paul Anderson Mr Brian Bowman Trans-Pennine Cup Winners: 2001 Mr Tommy Coleman Under 20’s Assistant Mr Frank Taylor Mr Steve Mayo Arriva Trains Cup Winners: 2004 Mr John Massey Conditioner LHF National League 1 Champions: Board of Management Mr Dan Ogden 2004 Mr Michael Norris - Chairman Physiotherapists LHF National League 1 Grand Final Mr Derek Beaumont Ms Emma Fletcher Winners: 2004 Mr Andy Mazey Ms Hannah Lloyd Northern Rail Cup Winners: Mr Alan Platt Mr John Stopford (Under 20's) 2006, 2011, 2013 Mr Steve Openshaw -

Halton, Sam Evans &Sons Ltd Man of the Match Lunts Heath Match Programme Sponsor Building Supplies

y 7 CLUB SPONSOR TODAY'S SPONSORS Big Match Host Halton, Sam Evans &Sons ltd Man of the Match Lunts Heath Match Programme Sponsor Building Supplies Match Ball Sponsor Alive &N/pp/fi' Spekeball VAUXHALL Auto Quest Northern Ford Premiership, Monday 16 April 2001, Kick Off 3.00pm STADIUM Official Matchday Magazine £1.50 N HaUon Bus Services in and around Widnes £r Runcorn Also to Prescot Huyton, Childwali Liverpool Chester^ St Helens £r Warrington Halton W i d n e s & R u n c o r n /A .-i-ii.Jd. 0151 423 3333 M o o r L a n e W i d n e s WA S 7 A F Ulf 'tii www.haltontransport.fsnet.co.uk 1 Ti r Ring us for details i £ m of all our services ;'’Tfj C!f-_ lUt A Li R Ring 1=1. I'-! traveline 1^.; if A Bam to 8pm Haiton,,,ort m daily, for times JMW floor ■TT^ traveline ofainocaie public transport info national bus 08706082608 services \ WIDN VIKIN C L U B O F r I Chief Patron Rt.HON LORD ASHLEY o £ Directors: AAChamber; SEvans, AHarris (Depu; TWFleet (Managing EBate, RBrown, JA )Mills, AMurt IHQuinn, FVo' Generai Manager: Hare Footbaii Secretary: Frj Head Coach: inners Assistant Coach: |oF Aiiiance Coach: Geor Hon. Surgeon: Mr P Club Doctors: Dr C 8. Dr PStockti Physiotherapis K F i s h e r & D V Hon Dental Surgail Mr IHawley P.A. Announcer: Chri TELEPHONE: o:i9f General: 0151-491 Club Shop; 0151-4; 1988,19 Fax:0151-423 2 T Floodlit Trophy Wifi Widnes Vikings Matchday Pro Designedand Produced by Tobin Desii Charity Sho Editedby Steve Fox. -

'^I/Jyj;Jj Yjhiih'nihiy .-Imi Yi-,L 'X

NORTHERN FORO PREMIERfiMIP BmummY PmmI B r i IPPfl '^i/JyJ;jJ yjhiIh'nihiy .-imi yi-,L 'X .. KEEP ATIGHT GRIP ON YOUR FINANCES If you don't keep agrip on your "Financial Health" how can you be sure your future is secure? ♦Mortgages* ♦Life Cover ♦Income Protection* ♦Pensions ♦ ♦Investments ♦ISA’s ♦Savings ♦Indiviclual Financial Review ♦ FREEPHONE 0800 015 4020 The Money Group Independent Financial Advisers Ihe Money Group, Independent Hnandal Advisers, Ocean House, 7Memorial Road, Waikden, Manchester M28 3AQ. Tel: 0161 790 4300. Fax: 0161 790 4399. Email: [email protected] Web: www.moneygroup.co.uk AMEMBER OF IFA NETWORK LIMITED WHICH IS REGULATED BY THE PERSONAL INVESTMENT AUTHORITY i *THESE PRODUCTS ARE NOT REGULATED BY THE PERSONAL INVESTMENT AUTHORITY. YOUR HOME IS AT RISK IF YOU DO NOT KEEP UP REPAYMENTS ON AMORTGAGE OR OTHER LOAN SECURED ON IT. WRITTEN DETAILS AVAILABLE ON REQUEST. ... with Christopher Hamilton Oldham Rugby League Football Club (1997) Limited A W A R M w e l c o m e t o 64 Union Street Boundary Park for this Oldham OL1 1DJ afternoon’s opening home Telephone: 0161 628 3677 NFP game against Choriey Fax: 0161 627 5700 Lynx. Henry Morris, their Club Shop: 0161 627 2141 Chairman, and everybody connected with the club CHAIRMAN Christopher Hamilton have had avery tough time DIRECTORS Christopher Hamiliton, Stewart over the last few months Hardacre, Sean Whitehead HEAD COACH culminating with the Mike Ford ASSISTANT COACH suspension of their Rugby John Henderson Football A L L I A N C E C O A C H League Haydn Walker Membership.