Immediations: the Humanitarian Impulse in Profound Impact on the Content of the Medium” (30)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 6: WAR and PEACE, SEX and VIOLENCE

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 6: WAR AND PEACE, SEX AND VIOLENCE JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/822 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME VOLUME 6 The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity Vol. 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence Jan M. Ziolkowski https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Vol. 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0149 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

SCMS 2019 Conference Program

CELEBRATING SIXTY YEARS SCMS 1959-2019 SCMSCONFERENCE 2019PROGRAM Sheraton Grand Seattle MARCH 13–17 Letter from the President Dear 2019 Conference Attendees, This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Formed in 1959, the first national meeting of what was then called the Society of Cinematologists was held at the New York University Faculty Club in April 1960. The two-day national meeting consisted of a business meeting where they discussed their hope to have a journal; a panel on sources, with a discussion of “off-beat films” and the problem of renters returning mutilated copies of Battleship Potemkin; and a luncheon, including Erwin Panofsky, Parker Tyler, Dwight MacDonald and Siegfried Kracauer among the 29 people present. What a start! The Society has grown tremendously since that first meeting. We changed our name to the Society for Cinema Studies in 1969, and then added Media to become SCMS in 2002. From 29 people at the first meeting, we now have approximately 3000 members in 38 nations. The conference has 423 panels, roundtables and workshops and 23 seminars across five-days. In 1960, total expenses for the society were listed as $71.32. Now, they are over $800,000 annually. And our journal, first established in 1961, then renamed Cinema Journal in 1966, was renamed again in October 2018 to become JCMS: The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. This conference shows the range and breadth of what is now considered “cinematology,” with panels and awards on diverse topics that encompass game studies, podcasts, animation, reality TV, sports media, contemporary film, and early cinema; and approaches that include affect studies, eco-criticism, archival research, critical race studies, and queer theory, among others. -

Oct-Dec Press Listings

ANTHOLOGY FILM ARCHIVES OCTOBER – DECEMBER PRESS LISTINGS OCTOBER 2013 PRESS LISTINGS MIX NYC PRESENTS: Tommy Goetz A BRIDE FOR BRENDA 1969, 62 min, 35mm MIX NYC, the producer of the NY Queer Experimental Film Festival, presents a special screening of sexploitation oddity A BRIDE FOR BRENDA, a lesbian-themed grindhouse cheapie set against the now-tantalizing backdrop of late-60s Manhattan. Shot in Central Park, Times Square, the Village, and elsewhere, A BRIDE FOR BRENDA narrates (quite literally – the story is told via female-voiced omniscient narration rather than dialogue) the experiences of NYC-neophyte Brenda as she moves into an apartment with Millie and Jane. These apparently unremarkable roommates soon prove themselves to be flesh-hungry lesbians, spying on Brenda as she undresses, attempting to seduce her, and making her forget all about her paramour Nick (and his partners in masculinity). As the narrator intones, “Once a young girl has been loved by a lesbian, it’s difficult to feel satisfaction from a man again.” –Thurs, Oct 3 at 7:30. TAYLOR MEAD MEMORIAL SCREENING Who didn’t love Taylor Mead? Irrepressible and irreverent, made of silly putty yet always sharp- witted, he was an underground icon in the Lower East Side and around the world. While THE FLOWER THIEF put him on the map, and Andy Warhol lifted him to Superstardom, Taylor truly made his mark in the incredibly vast array of films and videos he made with notables and nobodies alike. A poster child of the beat era, Mead was a scene-stealer who was equally vibrant on screen, on stage, or in a café reading his hilarious, aphoristic poetry. -

Soft in the Middle Andrews Fm 3Rd.Qxd 7/24/2006 12:20 PM Page Ii Andrews Fm 3Rd.Qxd 7/24/2006 12:20 PM Page Iii

Andrews_fm_3rd.qxd 7/24/2006 12:20 PM Page i Soft in the Middle Andrews_fm_3rd.qxd 7/24/2006 12:20 PM Page ii Andrews_fm_3rd.qxd 7/24/2006 12:20 PM Page iii Soft in the Middle The Contemporary Softcore Feature in Its Contexts DAVID ANDREWS The Ohio State University Press Columbus Andrews_fm_3rd.qxd 7/24/2006 12:20 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Andrews, David, 1970– Soft in the middle: the contemporary softcore feature in its contexts / David Andrews. p. cm. Includes bibliographic references and index. ISBN 0-8142-1022-8 (cloth: alk. paper)—ISBN 0-8142-9106 (cd-rom) 1. Erotic films— United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.S45A53 2006 791.43’65380973—dc22 2006011785 The third section of chapter 2 appeared in a modified form as an independent essay, “The Distinction ‘In’ Soft Focus,” in Hunger 12 (Fall 2004): 71–77. Chapter 5 appeared in a modified form as an independent article, “Class, Gender, and Genre in Zalman King’s ‘Real High Erotica’: The Conflicting Mandates of Female Fantasy,” in Post Script 25.1 (Fall 2005): 49–73. Chapter 6 is reprinted in a modified form from “Sex Is Dangerous, So Satisfy Your Wife: The Softcore Thriller in Its Contexts,” by David Andrews, in Cinema Journal 45.3 (Spring 2006), pp. 59–89. Copyright © 2006 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. Cover design by Dan O’Dair. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. -

The Legend of Henry Paris

When a writer The goes in search of Legend the great of auteur of the golden age of porn, she gets more than she bargained for Henry paris BY TONI BENTLEY Photography by Marius Bugge 108 109 What’s next? The fourth title that kept showing up on best-of lists of the golden age was The Opening of Misty Beethoven by Henry Paris. Who? Searching my favorite porn site, Amazon.com, I found that this 1975 film was just rereleased in 2012 on DVD with all the bells and whistles of a Criterion Collection Citizen Kane reissue: two discs (re- mastered, digitized, uncut, high- definition transfer) that include AAs a professional ballerina, I barely director’s commentary, outtakes, finished high school, so my sense of intakes, original trailer, taglines inadequacy in all subjects but classi- and a 45-minute documentary cal ballet remains adequately high. on the making of the film; plus a In the years since I became a writer, magnet, flyers, postcards and a my curiosity has roamed from clas- 60-page booklet of liner notes. sic literature to sexual literature to classic sexual literature. When Misty arrived in my mailbox days later, I placed the disc A few months ago, I decided to take a much-needed break in my DVD player with considerable skepticism, but a girl has to from toiling over my never-to-be-finished study of Proust, pursue her education despite risks. I pressed play. Revelation. Tolstoy and Elmore Leonard to bone up on one of our most interesting cultural phenomena: pornography. -

Portable Storage #3

3..Editorial 7..Pre-Build Ruins Alva Svoboda 12..Weird Stairways 58..Core Samples L. Jim Khennedy Craig William Lion 30..Beatnik Memories 64..San Francisco Expanded Ray Nelson John Fugazzi 31..Genders 68..Cole Valley Ray Nelson Kennedy Gammage 33..San Francisco, 1967 71..The Messiah Bunch Stacy Scott Terry Floyd 35..San Francisco Soliloquy 78..Hippies Kim Kerbis Robert Lichtman 38..Ghosts of San Francisco 82..From the Catacombs of Berkeley Don Herron Dale Nelson 41..Poets Don’t Have 88..The San Francisco Adventures Spare Change Michael Breiding Billy Wolfenbarger 107..What Was I G. Sutton Breiding 108..Staying Put Jay Kinney 112..Crap St. Ghost Dance D.S. Black 116..My San Francisco Century: 43..San Francisco Part One: 1970-2020 G. Sutton Breiding Grant Canfield 45..The City 146..House of Fools James Ru Joan Rector Breiding 48..Does A Moose Have an Id? 149..LoC$ Gary Mattingly 157..Dr. Dolittle 52..Me vs. The Giants Gary Casey Rich Coad 166..The Gorgon of Poses 56..Cliff House, Tafoni, Rock Lace, G. Sutton Breiding Use of Gyratory in a Sentence Jeanne N. Bowman “A time almost more than a place.” Susan Breiding 2 Artists in this Issue Frank Vacanti (Cover) Jim Ru (2, 30) Craig Smith (3, 40,51,56) Steve Stiles (6) Dave Barnett (31) Kurt Erichsen (45) John R. Benson(47, 70) Crow’s Caw Grant Canfield (116-145, William M. Breiding unless otherwise noted) I knew from day one when starting Portable Storage that I wanted to do a themed issue on San Francisco. -

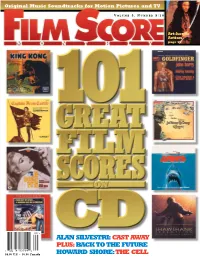

Back to the Future Howard Shore:The Cell

Original Music Soundtracks for Motion Pictures and TV V OLUME 5 , N UMBER 9 / 1 0 Art-house Action page 45 09 > ALAN SILVESTRI: CAST AWAY PLUS: BACK TO THE FUTURE 7 252 74 9 3 7 0 4 2 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada HOWARD SHORE: THE CELL Two new scores by the legendary composer of The Mission and A Fistful Of Dollars. GAUMONT AND LEGenDE enTrePriSES PReSENT Also Available: The Mission Film Music Vol. I Film Music Vol. II MUSicic BYBY ENNIO MORRICONE a ROLAND JOFFÉ film IN STORES FEBRUARY 13 ©2001 Virgin Records America, Inc. v CONTENTS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2000 cover story departments 26 101 Great Film Scores on CD 2 Editorial Here at the end of the year, century, millennium, Counting the Votes. whatever—FSM sticks out its collective neck and selects the ultimate list of influential, significant 4 News and enjoyable soundtracks released on CD. Hoyt Curtin, 1922-2000; By Joe Sikoryak, with John Bender, Jeff Bond, Winter Awards Winners. Jason Comerford, Tim Curran, Jeff Eldridge, 5 Record Label Jonathan Z. Kaplan, Lukas Kendall Round-up & Chris Stavrakis What’s on the way. 6 Now Playing 33 21 Should’a Been Contenders Movies and CDs in release. Go back to Back to the Future for 41 Missing in Action 8 Concerts ’round-the-clock analysis. Live performances page 16 around the world. f e a t u r e s 9 Upcoming Assignments 14 To Score or Not To Score? Who’s writing what Composer Alan Silvestri found his music for whom. struggling for survival in the post-production of Cast Away. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Jerry Douglas's <I>Tubstrip</I> and the Erotic Theatre of Gay Liberation

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Legitimate: Jerry Douglas's Tubstrip and the Erotic Theatre of Gay Liberation by Jordan Schildcrout The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 30, Number 1 (Fall 2017) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2017 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center From 1969 to 1974, after the premiere of Mart Crowley’s landmark gay play The Boys in the Band (1968) and before the establishment of an organized gay theatre movement with companies such as Doric Wilson’s TOSOS (The Other Side of Silence), there flourished a subgenre of plays that can best be described as gay erotic theatre. While stopping short of performing sex acts on stage, these plays featured copious nudity, erotic situations, and forthright depictions of gay desire. In the early years of gay liberation, such plays pushed at the boundaries between the “legitimate” theatre and pornography, and in the process created the most exuberant and affirming depictions of same-sex sexuality heretofore seen in the American theatre. Some of these works were extremely popular with gay audiences, but almost all were dismissed by mainstream critics, never published, and rarely revived. The most widely seen of these plays was Tubstrip (1973), written and directed by Jerry Douglas, whose career in the early 1970s was situated squarely at the intersection of legitimate theatre and pornography. An analysis of Tubstrip and its groundbreaking production history can illuminate an important but often overlooked chapter in the development of gay theatre in America. Tubstrip (which can be read “tub strip” or “tubs trip”) is a risqué farce set in a gay bathhouse, written by “A. -

Hammer Museum Summer 2011 Non Profit Org

Hammer Museum Summer 2011 Non Profit Org. US Postage 10899 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90024 USA Summer 2011 Calendar For additional program information: 310-443-7000 PAID Los Angeles, CA www.hammer.ucla.edu Permit no. 202 100% recycled paper (DETAIL), 1969–70. SYNTHETIC POLYMER AND GESSO ON NEWSPAPER. AND GESSO ON NEWSPAPER. 1969–70. SYNTHETIC POLYMER (DETAIL), 84.3 CM). COLLECTION OF GAIL AND TONY GANZ. ©THE ESTATE OF GEORGE PAUL THEK. OF GEORGE PAUL 84.3 CM). COLLECTION OF GAIL AND TONY GANZ. ©THE ESTATE x UNTITLED (DIVER) . IN. (56.5 16 ⁄ 3 33 x COVER: PAUL THEK COVER: PAUL 22 ¼ STUDIO. DOUGLAS M. PARKER PHOTOGRAPHY: 24 25 2 3 HAMMER NEWS A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR news NEW BOARD MEMBERS director Each spring the New York Times produces a special The Hammer is delighted to announce that Marcy Carsey and Anthony Pritzker the 1 “Museums Section” that focused this year on the have been appointed to the Museum’s Board of Directors. increasing role that technology plays as both a tool inside the walls of a museum, and as a portal for visitors into Marcy Carsey is partner and co-founder of the Carsey Werner Company, which from the workings of an institution. Indeed, the Hammer’s created and controls a library of award-winning television series, including “The website is often a visitor’s first experience of our collections, Cosby Show,” “Roseanne,” and “That 70’s Show.” She has been inducted into the exhibitions, and public programs. As the New York Times Academy of Television Arts & Sciences and the Broadcasting & Cable halls of fame. -

If at First You Dont Scceed

moft, VOLUME 16 NUMBER' 7 STONY BROOK, N.Y. FRDY OCOEf.17 -- ML, I (Sony Br4ookup Unve9]aiIed The "Stony Brook Cup,"' a perpetual trophy to IfAt First You Dont Scceed.., be awarded to the outstanding high,school soccer coach of the season in Suffolk County, was unveiled here last week._ Officials of the Suffolk. County Soccer Coaches Association were the first to view the trophy, which will be awarded by the association at its annual post-season dinner this fall. Donated by the soccer progamM at Stony Brook and the University's soccer alumni, the three foot silver cup will. reain with the coach of the winning high school team for one year and then move on to his successor. Soccer coach John-Ramsey noted'. "We feel that the recognition of coaching is sinfcnsince we draw many of our soccqr players from surrounding 4 towns."' This year one-third of the Patriot booters" 18-man squad has come to Stony Brook from Suffolk County high schools. "'Soccer is a very strong sport locally," Ramsey said, "due to the fine quality -of coaching. College coaches from across the country look to Long Island for players who have been taught t14 right way.si In the past, several Pat record holders have come from. Suffolk, including goalie Harry Prince from West Babylon, halfback Jack Esposito from Stony Brook Students Attempted Once Again To Register To Connetquot and center forward Don Foster from Southold. This year the Patriot squad is strengthened by Vote Under Their Campus Addresses, But W~ere Turned Away. -

British Films 1971-1981

Preface This is a reproduction of the original 1983 publication, issued now in the interests of historical research. We have resisted the temptations of hindsight to change, or comment on, the text other than to correct spelling errors. The document therefore represents the period in which it was created, as well as the hard work of former colleagues of the BFI. Researchers will notice that the continuing debate about the definitions as to what constitutes a “British” production was topical, even then, and that criteria being considered in 1983 are still valid. Also note that the Dept of Trade registration scheme ceased in May 1985 and that the Eady Levy was abolished in the same year. Finally, please note that we have included reminders in one or two places to indicate where information could be misleading if taken for current. David Sharp Deputy Head (User Services) BFI National Library August 2005 ISBN: 0 85170 149 3 © BFI Information Services 2005 British Films 1971 – 1981: - back cover text to original 1983 publication. What makes a film British? Is it the source of its finance or the nationality of the production company and/or a certain percentage of its cast and crew? Is it possible to define a British content? These were the questions which had to be addressed in compiling British Films 1971 – 1981. The publication includes commercial features either made and/or released in Britain between 1971 and 1981 and lists them alphabetically and by year of registration (where appropriate). Information given for each film includes production company, studio and/or major location, running time, director and references to trade paper production charts and Monthly Film Bulletin reviews as source of more detailed information.