WHEN the AFRIKA KORPS CAME to TEXAS Arnold Krammer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas POW Camp Hearne, Texas

Episode 2, 2005: Texas POW Camp Hearne, Texas Gwen: Our final story explores a forgotten piece of World War II history that unfolds on a mysterious plot of land deep in the heart of Texas. It’s summer, 1942, and Hitler’s armies are experiencing some of their first defeats, in North Africa. War offi- cials in Great Britain are in crisis. They have no more space to house the steadily mounting numbers of captured German soldiers. Finally, in August, America opened its borders to an emergency batch of prison- ers, marking the beginning of a little-known chapter in American history, when thousands of German soldiers marched into small town, U.S.A. More than 60 years later, that chapter is about to be reopened by a woman named Lisa Trampota, who believes the U.S. government planted a German prisoner of war camp right on her family land in Texas. Lisa Trampota: By the time I really got interested and wanted to learn more, everyone had died that knew anything about it. I’d love to learn more about my family’s history and how I’m connected with that property. Gwen: I’m Gwen Wright. I’ve come to Hearne, Texas, to find some answers to Lisa’s questions. Hi, Lisa? Lisa: Hi. Gwen: I’m Gwen. Lisa: Hi, Gwen, it’s very nice to meet you. Gwen: So, I got your phone call. Now tell me exactly what you’d like for me to find out for you. Lisa: Well, I heard, through family legend, that we owned some property outside of Hearne, and that in the 1940s the U.S. -

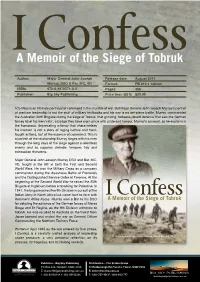

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 49 Number 2 Article 2 4-1-1974 Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946 Jake W. Spidle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Spidle, Jake W.. "Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946." New Mexico Historical Review 49, 2 (2021). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol49/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 93 AXIS INVASION OF THE AMERICAN WEST: POWS IN NEW MEXICO, 1942-1946 JAKE W. SPIDLE ON A FLAT, virtually treeless stretch of New Mexico prame, fourteen miles southeast of the town of Roswell, the wind now kicks up dust devils where Rommel's Afrikakorps once marched. A little over a mile from the Orchard Park siding of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific railroad line, down a dusty, still unpaved road, the concrete foundations of the Roswell Prisoner of War Internment Camp are still visible. They are all that are left from what was "home" for thousands of German soldiers during the period 1942-1946. Near Lordsburg there are similar ruins of another camp which at various times during the years 1942-1945 held Japanese-American internees from the Pacific Coast and both Italian and German prisoners of war. -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945

Forgotten and Unfulfilled: German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945- 1949 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Guy B. Aldridge May 2015 © 2015 Guy B. Aldridge. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Forgotten and Unfulfilled: German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945- 1949 by GUY B. ALDRIDGE has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Mirna Zakic Assistant Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract ALDRIDGE, GUY B., M.A., May 2015, History Forgotten and Unfulfilled: German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945- 1949 Director of Thesis: Mirna Zakic This thesis examines how local newspapers in the French Occupation Zone of Germany between 1945 and 1949 reflected social change. The words of the press show that, starting in 1945, the Christian narrative was the lens through which ‘average’ Germans conceived of their past and present, understanding the Nazi era as well as war guilt in religious terms. These local newspapers indicate that their respective communities made an early attempt to ‘come to terms with the past.’ This phenomenon is explained by the destruction of World War II, varying Allied approaches to German reconstruction, and unique social conditions in the French Zone. The decline of ardent religiosity in German society between 1945 and 1949 was due mostly to increasing Cold War tensions as well as the return of stability and normality. -

Afrika Korps from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Afrika Korps From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "DAK" redirects here. For other uses, see DAK (disambiguation). Navigation Main page This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Contents citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2008) Featured content The German Africa Corps (German: Deutsches Afrikakorps, DAK listen (help·info)), Deutsches Afrikakorps Current events or just the Afrika Korps, was the German expeditionary force in Libya and Tunisia Active 12 February 1941 – 13 May 1943 Random article during the North African Campaign of World War II. The reputation of the Afrika Korps Country Nazi Germany Donate to Wikipedia is synonymous with that of its first commander Erwin Rommel, who later commanded Branch Wehrmacht Heer the [1] Panzer Army Africa which evolved into the German-Italian Panzer Army Type Expeditionary Force Interaction (Deutsch-Italienische Panzerarmee) and Army Group Africa, all of which Afrika Korps was a distinct and principal component. Throughout the North African campaign, the Size Corps Help Afrika Korps fought against Allied forces until its surrender in May 1943. Garrison/HQ Tripoli, Italian Libya About Wikipedia Motto Ritterlich im Kriege, wachsam für den Community portal Contents Frieden Recent changes 1 Organization ("Chivalrous in War, Vigilant for Peace") Contact Wikipedia 2 Composition and terminology Colors Yellow, Brown 2.1 Ramcke Brigade -

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46

The Enemy in Colorado: German Prisoners of War, 1943-46 BY ALLEN W. PASCHAL On 7 December 1941 , the day that would "live in infamy," the United States became directly involved in World War II. Many events and deeds, heroic or not, have been preserved as historic reminders of that presence in the world conflict. The imprisonment of American sol diers captured in combat was a postwar curiosity to many Americans. Their survival, living conditions, and treatment by the Germans became major considerations in intensive and highly publicized investigations. However, the issue of German prisoners of war (POWs) interned within the United States has been consistently overlooked. The internment centers for the POWs were located throughout the United States, with different criteria determining the locations of the camps. The first camps were extensions of large military bases where security was more easily accomplished. When the German prisoners proved to be more docile than originally believed, the camps were moved to new locations . The need for laborers most specifically dic tated the locations of the camps. The manpower that was available for needs other than the armed forces and the war industries was insuffi cient, and Colorado, in particular, had a large agricultural industry that desperately needed workers. German prisoners filled this void. There were forty-eight POW camps in Colorado between 1943 and 1946.1 Three of these were major base camps, capable of handling large numbers of prisoners. The remaining forty-five were agricultural or other work-related camps . The major base camps in Colorado were at Colorado Springs, Trinidad, and Greeley. -

'Hospitality Is the Best Form of Propaganda': German Prisoners Of

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “Hospitality Is the Best Form of Propaganda”: German Prisoners of War in Western Massachusetts, 1944-1946.” Author: John C. Bonafilia Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 44, No. 1, Winter 2016, pp. 44-83. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 44 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2016 German POWs Arrive in Western Massachusetts Captured German troops enter Camp Westover Field in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. Many of the prisoners would go on to work as farmhands contracted out to farms in the Pioneer Valley. Undated photo. Courtesy of Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base. 45 “Hospitality Is the Best Form of Propaganda”: German Prisoners of War in Western Massachusetts, 1944–1946 JOHN C. BONAFILIA Abstract: In October 1944, the first German prisoners of war (POWs) arrived at Camp Westover Field in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. Soon after, many of these prisoners were transported to farms throughout Hampshire, Franklin, and Hampden Counties to help local farmers with their harvest. The initial POW workforce numbered 250 Germans, but farmers quickly requested more to meet the demands of the community and to free up American soldiers for international service. -

Tennessee State Library and Archives Colonel Harry E. Dudley Papers

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives Colonel Harry E. Dudley Papers, 1916-1966 COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Dudley, Harry E., 1895-1967 Inclusive Dates: 1916-1966, bulk 1941-1946 Scope & Content: Collection contains approximately 3.75 cubic feet of documents and photographs primarily related to Colonel Harry E. Dudley's military career. While there is some material related to his time in the United States Marine Corps during World War I, and some material is related to his time in the National Guard and in the 35th Infantry Division prior to World War II, the bulk of the material within the collection is related to his time as the commanding officer of the internment camp for Italian and German prisoners of war in Crossville, Tennessee. The Italian prisoners of war were transferred to a different camp shortly after Dudley took over Camp Crossville, so most of the documents were created by or related to the German prisoners. The documents generated by the prisoners are usually in their native language (i.e. Italian or German), but they are also usually accompanied by translations done by U.S. Army personnel. However, the collection's processing archivist translated several documents, including: (1) the threatening note (Box 1, Folder 31), (2) the memo to the German prisoners of war notifying them of Germany's surrender (Box 2, Folder 28), and (3) the Wehrmacht report (Box 5, Folder 12). Portions of the report by the German prisoners of war to the Legation of Switzerland about Camp Crossville (Box 3, Folder 13) were translated by U.S. -

The Greatest Military Reversal of South African Arms: the Fall of Tobruk 1942, an Avoidable Blunder Or an Inevitable Disaster?

THE GREATEST MILITARY REVERSAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARMS: THE FALL OF TOBRUK 1942, AN AVOIDABLE BLUNDER OR AN INEVITABLE DISASTER? David Katz1 Abstract The surrender of Tobruk 70 years ago was a major catastrophe for the Allied war effort, considerably weakening their military position in North Africa, as well as causing political embarrassment to the leaders of South Africa and the United Kingdom. This article re-examines the circumstances surrounding and leading to the surrender of Tobruk in June 1942, in what amounted to the largest reversal of arms suffered by South Africa in its military history. By making use of primary documents and secondary sources as evidence, the article seeks a better understanding of the events that surrounded this tragedy. A brief background is given in the form of a chronological synopsis of the battles and manoeuvres leading up to the investment of Tobruk, followed by a detailed account of the offensive launched on 20 June 1942 by the Germans on the hapless defenders. The sudden and unexpected surrender of the garrison is examined and an explanation for the rapid collapse offered, as well as considering what may have transpired had the garrison been better prepared and led. Keywords: South Africa; HB Klopper; Union War Histories; Freeborn; Gazala; Eighth Army; 1st South African Division; Court of Enquiry; North Africa. Sleutelwoorde: Suid-Afrika; HB Klopper; Uniale oorlogsgeskiedenis; Vrygebore; Gazala; Agste Landmag; Eerste Suid-Afrikaanse Bataljon; Hof van Ondersoek; Noord-Afrika. 1. INTRODUCTION This year marks the 70th anniversary of the fall of Tobruk, the largest reversal of arms suffered by South Africa in its military history. -

Japanese Prisoners of War in America Author(S): Arnold Krammer Reviewed Work(S): Source: Pacific Historical Review, Vol

Japanese Prisoners of War in America Author(s): Arnold Krammer Reviewed work(s): Source: Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 52, No. 1 (Feb., 1983), pp. 67-91 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3639455 . Accessed: 13/01/2012 10:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pacific Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org Japanese Prisoners of War in America Arnold Krammer The author is professor of history in Texas A r M University. F EWAMERICANS today recall that the nation maintained 425,000 enemyduring the SecondWorld War in prisoner-of-warcamps from New Yorkto California.The majorityof these captiveswere Ger- mans, followedby Italians and Japanese.The incarcerationof the 5,424 Japanesesoldiers and sailorsin the United States,'most cap- tured involuntarilyduring the bloody battles of the South Pacific, testedthe formidableingenuity of the WarDepartment. The veryfirst prisonerof war capturedby Americanforces was Japanese.Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki,the