The Music of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music

Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Master Thesis Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music submitted by Venkatesh Kulkarni submitted July 29, 2014 Supervisor / Advisor Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ Reviewers Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ International Audio Laboratories Erlangen A Joint Institution of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-N¨urnberg (FAU) and Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS ERKLARUNG¨ Erkl¨arung Hiermit versichere ich an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstst¨andig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus anderen Quellen oder indirekt ubernommenen¨ Daten und Konzepte sind unter Angabe der Quelle gekennzeichnet. Die Arbeit wurde bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland in gleicher oder ¨ahnlicher Form in einem Verfahren zur Erlangung eines akademischen Grades vorgelegt. Erlangen, July 29, 2014 Venkatesh Kulkarni i Master Thesis, Venkatesh Kulkarni ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna, whose expertise, understanding and patience added considerably to my learning experience. I appreciate his vast knowledge and skill in many areas (e.g., signal processing, Carnatic music, ethics and interaction with participants).He provided me with direction, technical support and became more of a friend, than a supervisor. A very special thanks goes out to my Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨uller,without whose motivation and encouragement, I would not have considered a graduate career in music signal analysis research. Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨ulleris the one professor/teacher who truly made a difference in my life. He was always there to give his valuable and inspiring ideas during my thesis which motivated me to think like a researcher. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

“I Cannot Live Without Music”

INTERVIEW “I cannot live without music” Swati Tirunal was undoubtedly one of the most important modern composers, one who included Hindustani styles in his compositions. Nowadays it has become fashionable to say you must avoid Hindustani in Carnatic music or the other way around. But looking back, Bhimsen Joshi was among those south Indians who became luminaries in the north Indian style. How many south Indians are really open to Hindustani music is debatable. The late M.S. Gopalakrishnan was very competent in the Hindustani field, and my colleague Sanjay Subrahmanyan is a Carnatic musician open to Hindustani ragas – he sings a Rama Varma at the Swarasadhana workshop focussing on Swati Tirunal’s compositions pallavi in Bagesree, for instance. Then again there are ‘fundamentalist’ groups Well known Carnatic vocalist Rama Varma was in Chennai recently to who think Behag, Sindhubhairavi, conduct a two-day workshop (9 and 10 February 2013) Swarasadhana, Yamunakalyani, Sivaranjani and their at the Satyananda Yoga Centre at Triplicane. Here he speaks of the event, ilk should be totally done away with. his journey in classical music and his thoughts on the changing trends of the art form. Rama Varma How did Swarasadhana happen? in conversation with I have been teaching in a village called Perla near Mangalore for the past M. Ramakrishnan four years, at a music school called Veenavadini, run by the musician Yogeesh Sharma. He invites musicians to visit there once a year. Four years ago Veenavadini invited me. They enjoyed my teaching and Do you follow the same style of teaching I enjoyed being there too, and my visits became regular. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

A Novel Hybrid Approach for Retrieval of the Music Information

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 12, Number 24 (2017) pp. 15011-15017 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com A Novel Hybrid Approach for Retrieval of the Music Information Varsha N. Degaonkar Research Scholar, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication, JSPM’s Rajarshi Shahu College of Engineering, Pune, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0002-7048-1626 Anju V. Kulkarni Professor, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication, Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Technology, Pimpri, Pune, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0002-3160-0450 Abstract like automatic music annotation, music analysis, music synthesis, etc. The performance of existing search engines for retrieval of images is facing challenges resulting in inappropriate noisy Most of the existing human computation systems operate data rather than accurate information searched for. The reason without any machine contribution. With the domain for this being data retrieval methodology is mostly based on knowledge, human computation can give best results if information in text form input by the user. In certain areas, machines are taken in a loop. In recent years, use of smart human computation can give better results than machines. In mobile devices is increased; there is a huge amount of the proposed work, two approaches are presented. In the first multimedia data generated and uploaded to the web every day. approach, Unassisted and Assisted Crowd Sourcing This data, such as music, field sounds, broadcast news, and techniques are implemented to extract attributes for the television shows, contain sounds from a wide variety of classical music, by involving users (players) in the activity. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

MRIDANGA SYLLABUS for MA (CBCS) Effective from 2014-15

BANGALORE UNIVERSITY P.G. DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS JNANABHARATHI, BANGALORE-560056 MRIDANGA SYLLABUS FOR M.A (CBCS) Effective from 2014-15 Dr. B.M. Jayashree. Professor of Music Chairperson, BOS (PG) M.A. MRIDANGA Semester scheme syllabus CBCS Scheme of Examination, continuous Evaluation and other Requirements: 1. ELIGIBILITY: A Degree music with Mridanga as one of the optional subject with at least 50% in the concerned optional subject an merit internal among these applicant Of A Graduate with minimum of 50% marks secured in the senior grade examination of Mridanga conducted by secondary education board of Karnataka OR a graduate with a minimum of 50% marks secured in PG Diploma or 2 years diploma or 4 year certificate course in Mridanga conducted either by any recognized Universities of any state out side Karnataka or central institution/Universities Any degree with: a) Any certificate course in Mridanga b) All India Radio/Doordarshan gradation c) Any diploma in Mridanga or five years of learning certificate by any veteran musician d) Entrance test (practical) is compulsory for admission. 2. M.A. Mridanga course consists of four semesters. 3. First semester will have three theory paper (core), three practical papers (core) and one practical paper (soft core). 4. Second semester will have three theory papers (core), three practical papers (core), one is project work/Dissertation practical paper and one is practical paper (soft core) 5. Third semester will have two theory papers (core), three practical papers (core) and one is open Elective Practical paper 6. Fourth semester will have two theory Papers (core) two practical papers (core), one project work and one is Elective paper. -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

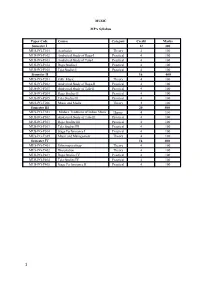

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute Regulations And Programme of Studies B. A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) (Review) - 1 - UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS MAHATMA GANDHI INSTITUTE PART I General Regulations for B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 1. Programme title: B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 2. Objectives To equip the student with further knowledge and skills in Vocal Hindustani Music and proficiency in the teaching of the subject. 3. General Entry Requirements In accordance with the University General Entry Requirements for admission to undergraduate degree programmes. 4. Programme Requirement A post A-Level MGI Diploma in Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) or an alternative qualification acceptable to the University of Mauritius. 5. Programme Duration Normal Maximum Degree (P/T): 2 years 4 years (4 semesters) (8 semesters) 6. Credit System 6.1 Introduction 6.1.1 The B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) programme is built up on a 3- year part time Diploma, which accounts for 60 credits. 6.1.2 The Programme is structured on the credit system and is run on a semester basis. 6.1.3 A semester is of a duration of 15 weeks (excluding examination period). - 2 - 6.1.4 A credit is a unit of measure, and the Programme is based on the following guidelines: 15 hours of lectures and / or tutorials: 1 credit 6.2 Programme Structure The B.A Programme is made up of a number of modules carrying 3 credits each, except the Dissertation which carries 9 credits. 6.3 Minimum Credits Required for the Award of the Degree: 6.3.1 The MGI Diploma already accounts for 60 credits. -

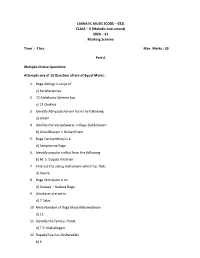

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B.