A Statistical Look at Roger Clemens' Pitching Career

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

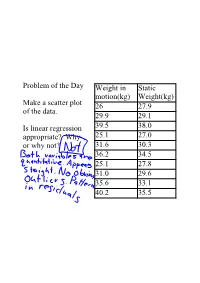

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

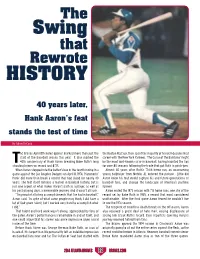

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds Gavel.) Good Afternoon and Welcome to the National Press Club. My Name Is Donna Leinwand. I'm a Repor

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH JEFF IDELSON SUBJECT: JEFF IDELSON, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME, IS SCHEDULED TO SPEAK AT A NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON MAY 11. HALL OF FAME THIRD BASEMAN BROOKS ROBINSON WILL BE A SPECIAL GUEST. MODERATOR: DONNA LEINWAND, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MAY 11, 2009 (C) COPYRIGHT 2009, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Donna Leinwand. I’m a reporter at USA Today and I’m president of the National Press Club. We’re the world’s leading professional organization for journalists and are committed to a future of journalism by providing informative programming, journalism education and fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. On behalf of our 3,500 members worldwide, I’d like to welcome our speaker and our guests in the audience today. I’d also like to welcome those of you who are watching us on C-Span. We’re looking forward to today’s speech, and afterwards, I’ll ask as many questions from the audience as time permits. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

San Francisco Giants

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME NOTES 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (67-59) at WASHINGTON NATIONALS (73-53) RHP Tim Hudson (8-9, 3.03) vs. RHP Doug Fister (12-3, 2.20) Game #128/Road Game 64 • Friday, August 22, 2014 • Nationals Park • 4:05 p.m. (PT) • CSN Bay Area UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Saturday, August 23 at Washington (1:05): RHP Tim Lincecum (10-8, 4.48) vs. RHP Jordan Zimmermann (8-5, 2.97) - CSN Bay Area • Sunday, August 24 at Washington (10:35am): RHP Ryan Vogelsong (7-9, 3.73) vs. RHP Stephen Strasburg (10-10, 3.41) - CSN Bay Area Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio). All home games and road games in LA, SD and OAK broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). THE GIANTS GIANTS ON THIS ROAD TRIP TO GIANTS BY THE NUMBERS • Have won five of their last seven games and enter tonight's CHICAGO AND WASHINGTON game 3.5 games behind the first place Dodgers in the Games . 3 NOTE 2014 National League West . Record . 2-1 Average . .325 (37114) Current Standing in NL West: . 2nd Avg . w/RISP . .237 (9x38) Series Record: . 22-15-3 IN THE STANDINGS Runs Per Game . 4 .7 (14) Series Record, home: . 11-8-3 • San Francisco currently owns the fifth-highest winning Home Runs . 3 Series Record, road: . 11-7-0 percentage in the NL behind Washington (73-53, .579), Stolen Bases . -

Sabermetrics: the Past, the Present, and the Future

Sabermetrics: The Past, the Present, and the Future Jim Albert February 12, 2010 Abstract This article provides an overview of sabermetrics, the science of learn- ing about baseball through objective evidence. Statistics and baseball have always had a strong kinship, as many famous players are known by their famous statistical accomplishments such as Joe Dimaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams’ .406 batting average in the 1941 baseball season. We give an overview of how one measures performance in batting, pitching, and fielding. In baseball, the traditional measures are batting av- erage, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage, but modern measures such as OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) are better in predicting the number of runs a team will score in a game. Pitching is a harder aspect of performance to measure, since traditional measures such as winning percentage and earned run average are confounded by the abilities of the pitcher teammates. Modern measures of pitching such as DIPS (defense independent pitching statistics) are helpful in isolating the contributions of a pitcher that do not involve his teammates. It is also challenging to measure the quality of a player’s fielding ability, since the standard measure of fielding, the fielding percentage, is not helpful in understanding the range of a player in moving towards a batted ball. New measures of fielding have been developed that are useful in measuring a player’s fielding range. Major League Baseball is measuring the game in new ways, and sabermetrics is using this new data to find better mea- sures of player performance. -

The Organizational Life of the College Football Player: an Exploration of Injury

The Organizational Life of the College Football Player: An Exploration of Injury, Football Culture, and Organizational Dialectics A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Kenneth M. Sibal June 2011 © 2011 Kenneth M. Sibal. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Organizational Life of the College Football Player: An Exploration of Injury, Football Culture, and Organizational Dialectics by KENNETH M. SIBAL has been approved for the School of Communication Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Claudia L. Hale Professor of Communication Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT SIBAL, KENNETH M., Ph.D., June 2011, Communication Studies The Organizational Life of the College Football Player: An Exploration of Injury, Football Culture, and Organizational Dialectics Director of Dissertation: Claudia L. Hale This dissertation attempts to better understand the lives of college football players. The project begins with the assumption that the ways individuals talk about their experiences have a significant impact on others. An organizational framework is used to appreciate the central importance of communication in coordinating organizational relationships and developing impressions. College football players were gathered from three separate institutions representing different competitive levels of college football. Through interviews, participants were invited to provide stories that reflected their understandings of what it means to play college football. Because the intent of this study was to better understand issues related to the culture of playing football, common themes were derived from those interviews in an attempt to answer four separate research questions. -

The Rules of Scoring

THE RULES OF SCORING 2011 OFFICIAL BASEBALL RULES WITH CHANGES FROM LITTLE LEAGUE BASEBALL’S “WHAT’S THE SCORE” PUBLICATION INTRODUCTION These “Rules of Scoring” are for the use of those managers and coaches who want to score a Juvenile or Minor League game or wish to know how to correctly score a play or a time at bat during a Juvenile or Minor League game. These “Rules of Scoring” address the recording of individual and team actions, runs batted in, base hits and determining their value, stolen bases and caught stealing, sacrifices, put outs and assists, when to charge or not charge a fielder with an error, wild pitches and passed balls, bases on balls and strikeouts, earned runs, and the winning and losing pitcher. Unlike the Official Baseball Rules used by professional baseball and many amateur leagues, the Little League Playing Rules do not address The Rules of Scoring. However, the Little League Rules of Scoring are similar to the scoring rules used in professional baseball found in Rule 10 of the Official Baseball Rules. Consequently, Rule 10 of the Official Baseball Rules is used as the basis for these Rules of Scoring. However, there are differences (e.g., when to charge or not charge a fielder with an error, runs batted in, winning and losing pitcher). These differences are based on Little League Baseball’s “What’s the Score” booklet. Those additional rules and those modified rules from the “What’s the Score” booklet are in italics. The “What’s the Score” booklet assigns the Official Scorer certain duties under Little League Regulation VI concerning pitching limits which have not implemented by the IAB (see Juvenile League Rule 12.08.08). -

Name of the Game: Do Statistics Confirm the Labels of Professional Baseball Eras?

NAME OF THE GAME: DO STATISTICS CONFIRM THE LABELS OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ERAS? by Mitchell T. Woltring A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Leisure and Sport Management Middle Tennessee State University May 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Colby Jubenville Dr. Steven Estes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not be where I am if not for support I have received from many important people. First and foremost, I would like thank my wife, Sarah Woltring, for believing in me and supporting me in an incalculable manner. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Julie Woltring, for always supporting and encouraging me to make myself a better person. I would be remiss to not personally thank Dr. Colby Jubenville and the entire Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Without Dr. Jubenville convincing me that MTSU was the place where I needed to come in order to thrive, I would not be in the position I am now. Furthermore, thank you to Dr. Elroy Sullivan for helping me run and understand the statistical analyses. Without your help I would not have been able to undertake the study at hand. Last, but certainly not least, thank you to all my family and friends, which are far too many to name. You have all helped shape me into the person I am and have played an integral role in my life. ii ABSTRACT A game defined and measured by hitting and pitching performances, baseball exists as the most statistical of all sports (Albert, 2003, p. -

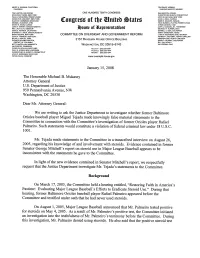

@Ongre ßß of Tlle Mnitù $¡Tutts MARK E

HENRY A WAXMAN. CALIFORNIA. TOM DAVIS, VIRGINIA, CHAIRMAN RANKING MINORTTY MEI\¡BER TOM LANTOS, CALIFORNIA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS DAN BURTON, INDIANA EOOLPHUS TOWNS. NEW YORK CHFISTOPHER SHAYS, CONNECTICUI PAUL E. KANJORSKI, PENNSYLVANIA JOHN M. McHUGH, NEW YOBK CAFOLYN B. MALONEY, NEW YORK JOHN L. MICA, FLORIDA ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, MARYLAND @ongre ßß of tlle Mnitù $¡tutts MARK E. SOUDEB, INDIANA DENNIS J. KUCINICH, OHIO TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, PENNSYLVANIA DANNY K. DAVIS. ILLINOIS .l.|ERNEY. JOHN F. MASSACHUSETTS JOHN J. DUNCAN. JR.. TENNESSEE WI\,'. LACY CLAY. MISSOURI Tâouse of lßepreøent¡tibes MICHAEL R. TUFNER, OHIO DIANE E. WATSON, CALIFORNIA DAFRELL E. ISSA, CALIFORNIA BRIAN HIGGINS, NEWYORK coMMTTTEEoNovERSTcHTANDGovERNMENTREFoRM l"'ilillTiffilîäÄ;LftÌ"."""^ JOHN A. YARI\,IUTH. KENTUCKY PATFICK T. McHENRY, NORTH CAROLINA BRUCE L. BRALEY. IOWA VIFGINIA FO)C(, NORTH CAROLINA ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON. 2157 Rnveunru House Ornce Butorrue BRIAN P. BILBRAY, CALIFORNIA DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA BILL SALI, IDAHO BETTY MGCOLLUM, MINNESOTA WnsHrrucroru. DC 2051 5-61 43 JIM JORDAN, OHIO JIM COOPER, TENNESSEE CHRIS VAN HOLLEN. MARYLAND MruoBrû (202) 22H051 PAULW. HODES, NEV,/ HAI\¡PSHIRE FÂGrMrE (202) 225-4784 CHRISTOPHER S. MUBPHY, CONNECTICUT MrNoÊrw (202) 22H074 JOHN P. SARBANES, MARYLAND PETÉR WELCH, VEBMONT www.oversight. house.gov January 15,2008 The Honorable Michael B. Mukasey Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW V/ashington, DC 20530 Dear Mr. Attorney General: 'We are writing to ask the Justice Department to investigate whether former Baltimore Orioles baseball player Miguel Tejada made knowingly false material statements to the Committee in connection with the Committee's investigation of former Orioles player Rafael Palmeiro. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Saturday, April 18, 2020 * The Boston Globe Fenway Park is ready to play ball, even though we are not Stan Grossfeld The grass is perfect and the old ballpark is squeaky clean — it was scrubbed and disinfected for viral pathogens for three days in March. Spending a few hours at Fenway Park is good for the soul. The ballpark is totally silent. The mound and home plate are covered by tarps and the foul lines aren’t drawn yet, but it feels as if there still could be a game played today. The sun’s warmth reflecting off The Wall feels good. The tug of the past is all around but the future is the great unknown. In Fenway, zoom is still a word to describe a Chris Sale fastball, not a video conferencing app. Old friend Terry Francona and the Cleveland Indians would have been here this weekend and there would’ve been big hugs by the batting cage and the rhythmic crack of bat meeting ball. But now gaining access is nearly impossible and includes health questions and safety precautions and a Fenway security escort. Visitors must wear a respiratory mask, gloves, and practice social distancing, larger than the lead Dave Roberts got on Mariano Rivera in the 2004 ALCS. Carissa Unger of Green City Growers in Somerville is planting organic vegetables for Fenway Farms, located on the rooftop of the park. She is one of the few allowed into the ballpark. The harvest this year all will be donated to a local food pantry.