THE PROMONTORY APARTMENTS 5530-5532 South Shore Drive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alejandro Cervilla García* the Skin and Bones of Structure. a Brief

2019 2(58) DOI: 10.5277/arc190202 Alejandro Cervilla García* The skin and bones of structure. A brief history of how Mies van der Rohe revealed the skeleton of the house Szkielet i obudowa. Krótka historia tego, jak Mies van der Rohe wyeksponował konstrukcję budynku In 1907, Mies van der Rohe built his first work, Riehl bas-relief, defining a wall. The second device reminds us House, in Potsdam, a classic house with a rectangular of the classic Greek tool of the peristyle in the semi-open floor plan, a structure of brick load-bearing walls with spaces that surrounded temples2. But in essence, this first a plaster of slaked lime and a sloping roof (Fig. 1). home by Mies is a clear example of a house with a hidden Although, the construction of reinforced concrete build- structure. There is no clue to its structural reality. You ings had already begun in Europe in 1890 [2], [3, cannot see the brickwork, the formation of the lintels, or pp. 54–62], and the first steel-structured skyscrapers in the thickness of the walls. Neither can you see the base of America had made their appearance in 1880 [4, pp. 365– the walls nor the wooden frame that constitutes the roof. 446], the use of concrete and steel had not yet become This compact, symmetrical and compartmentalized widespread, so Mies used traditional construction meth- house scheme, with a brick load-bearing wall structure ods in this first work. and sloping roof served as a model for a whole series of On the outside of the house we observe the trace of sub sequent houses: Perls house (Zehlendorf, Berlin, 1911), a structure that wants to reveal itself. -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

Single Family Residence Design Guidelines

ADOPTED BY SANTA BARBARA CITY COUNCIL IN 2007 Available at the Community Development Department, 630 Garden Street, Santa Barbara, California, (805) 564-5470 or www.SantaBarbaraCA.gov 2007 CITY COUNCIL, 2007 ARCHITECTURAL BOARD OF REVIEW, 2007 Marty Blum, Mayor Iya Falcone Mark Wienke Randall Mudge Brian Barnwell Grant House Chris Manson-Hing Dawn Sherry Das Williams Roger Horton Jim Blakeley Clay Aurell Helene Schneider Gary Mosel SINGLE FAMILY DESIGN BOARD, 2010 UPDATE PLANNING COMMISSION, 2007 Paul R. Zink Berni Bernstein Charmaine Jacobs Bruce Bartlett Glen Deisler Erin Carroll George C. Myers Addison Thompson William Mahan Denise Woolery John C. Jostes Harwood A. White, Jr. Gary Mosel Stella Larson PROJECT STAFF STEERING COMMITTEE Paul Casey, Community Development Director Allied Neighborhood Association: Bettie Weiss, City Planner Dianne Channing, Chair & Joe Guzzardi Jaime Limón, Design Review Supervising Planner City Council: Helene Schneider & Brian Barnwell Heather Baker, Project Planner Planning Commission: Charmaine Jacobs & Bill Mahan Jason Smart, Planning Technician Architectural Board of Review: Richard Six & Bruce Bartlett Tony Boughman, Planning Technician (2009 Update) Historic Landmarks Commission: Vadim Hsu GRAPHIC DESIGN, PHOTOS & ILLUSTRATIONS HISTORIC LANDMARKS COMMISSION, 2007 Alison Grube & Erin Dixon, Graphic Design William R. La Voie Susette Naylor Paul Poirier & Michael David Architects, Illustrations Louise Boucher H. Alexander Pujo Bill Mahan, Illustrations Steve Hausz Robert Adams Linda Jaquez & Kodiak Greenwood, -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies Van Der Rohe Award: a Tribute to Bauhaus

AT A GLANCE EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies van der Rohe Award: A tribute to Bauhaus The EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture (also known as the EU Mies Award) was launched in recognition of the importance and quality of European architecture. Named after German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a figure emblematic of the Bauhaus movement, it aims to promote functionality, simplicity, sustainability and social vision in urban construction. Background Mies van der Rohe was the last director of the Bauhaus school. The official lifespan of the Bauhaus movement in Germany was only fourteen years. It was founded in 1919 as an educational project devoted to all art forms. By 1933, when the Nazi authorities closed the school, it had changed location and director three times. Artists who left continued the work begun in Germany wherever they settled. Recognition by Unesco The Bauhaus movement has influenced architecture all over the world. Unesco has recognised the value of its ideas of sober design, functionalism and social reform as embodied in the original buildings, putting some of the movement's achievements on the World Heritage List. The original buildings located in Weimar (the Former Art School, the Applied Art School and the Haus Am Horn) and Dessau (the Bauhaus Building and the group of seven Masters' Houses) have featured on the list since 1996. Other buildings were added in 2017. The list also comprises the White City of Tel-Aviv. German-Jewish architects fleeing Nazism designed many of its buildings, applying the principles of modernist urban design initiated by Bauhaus. -

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Best Practices Single-Family Residences

SITE PLANNING best practices single-family residences for aesthetic review by the city of coral gables board of architects 2018 1 SINGLE-FAMILY RESIDENCE BEST PRACTICES July 2018 table of contents 1. Purpose & Uses 2. Site Planning 3. Architecture 4. Checklist Purpose & Uses The purpose of the City of Coral Gables, Florida Zoning Code is to implement the Comprehensive Plan (CP) of the City pursuant to Chapter 163, Florida Statutes for the protection and promotion of the safety, health, comfort, morals, convenience, peace, prosperity, appearance and general welfare of the City and its inhabitants. ~ Zoning Code Section 1-103 Purpose of the City of Coral Gables Zoning Code PURPOSE & USE Single-Family Residential (SFR) District The Single-Family Residential (SFR) District is intended to accommodate low density, single-family dwelling units with adequate yards and open space that characterize the residential neighborhoods of the city. The city is unique not only in South Florida but in the country for its historic and archi- tectural treasures, its leafy canopy, and its well-defined and livable neighborhoods. These residential areas, with tree-lined streets and architecture of harmonious proportion and human scale, provide an oasis of charm and tranquility in the midst of an increasingly built-up metropolitan environment. The intent of the Single-Family Residential code is to protect the distinctive character of the city, while encouraging excellent architectural design that is responsible and responsive to the individual context of the city’s diverse neighborhoods. The single-family regulations, as well as the design and performance standards in the Zoning Code, seek to ensure that the renovation of residences as well as the building of residences is in accord with the civic pride and sense of stewardship felt by the citizens of Coral Gables. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) r~ _ B-1382 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Completelhe National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property I historic name Highfield House____________________________________________ other names B-1382___________________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 4000 North Charles Street ____________________ LJ not for publication city or town Baltimore___________________________________________________ D vicinity state Maryland code MD county Baltimore City code 510 zip code 21218 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E] meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally D statewide ^ locally. -

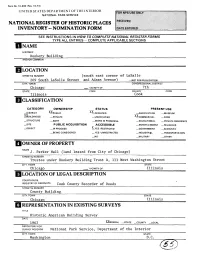

Iowner of Property Name J

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Rookery Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER (south east corner of LaSalle 209 South LaSalle Street and Adams Avenue) _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago VICINITY OF 7th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois Cook CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE vv _DISTRICT A1LOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM VV AmJILDING(S) _ PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED AACOMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME J. Parker Hall (land leased from City of Chicago) STREET & NUMBER Trustee under Rookery Building Trust A, 111 West Washington Street CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago VICINITY OF Illinois LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS'. Cook County Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER County BuiIding CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Illinois REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Building Survey DATE 1963 X)£EDERAL _STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Department of the Interior CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED XX_0 RIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XX.ALTERED _MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Completed in 1886 at a cost of $1,500,000, the Rookery contained 4,765,500 cubic feet of space. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago

CTBUH Research Paper ctbuh.org/papers Title: Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Author: Kheir Al-Kodmany, University of Illinois at Chicago Subjects: Keyword: Social Media Publication Date: 2019 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 8 Number 2 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. -

Wurlington Press Order Form Date

Wurlington Press Order Form www.Wurlington-Bros.com Date Build Your Own Chicago postcards Build Your Own New York postcards Posters & Books Quantity @ Quantity @ Quantity @ $ Chicago’s Tallest Bldgs Poster 19" x 28" 20.00 $ $ $ Water Tower Postcard AR-CHI-1 2.00 Flatiron Building AR-NYC-1 2.00 Louis Sullivan Doors Poster 18” x 24” 20.00 $ $ $ Chicago Tribune Tower AR-CHI-2 2.00 Empire State Building AR-NYC-2 2.00 Auditorium Bldg Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ $ $ AR-NYC-3 3.5” x 5.5” Wrigley Building AR-CHI-3 2.00 Citicorp Center 2.00 John Hancock Memo Book 4.95 $ $ $ AT&T Building AR-NYC-4 2.00 Pritzker Pavilion Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 Sears Tower AR-CHI-4 2.00 $ $ Rookery Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ Chrysler Building AR-NYC-5 2.00 John Hancock Center AR-CHI-5 2.00 $ $ American Landmarks Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 $ Lever House AR-NYC-6 2.00 AR-CHI-6 Reliance Building 2.00 $ $ U.S. Capitol Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 AR-NYC-7 $ Seagram Building 2.00 Bahai Temple AR-CHI-7 2.00 $ $ Santa’s Workshop Cut & Asssemble Book 12.95 Woolworth Building AR-NYC-8 2.00 $ Marina City AR-CHI-9 2.00 Haunted House Cut & Asssemble Book $12.95 $ Lipstick Building AR-NYC-9 2.00 $ $ 860 Lake Shore Dr Apts AR-CHI-10 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Book 30.00 $ Hearst Tower AR-NYC-10 2.00 $ $ Lake Point Tower AR-CHI-11 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Zines (per issue) 2.75 $ AR-NYC-11 UN Headquarters 2.00 $ $ Flood and Flotsam Book 16.00 Crown Hall AR-CHI-12 2.00 $ 1 World Trade Center AR-NYC-12 2.00 $ AR-CHI-13 35 E.