How Pinehurst's George Dunlap Jr. and Sr. Mastered the Worlds Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMATEUR CHAMPIONSHIP? • for AH Match Play •

THE AMATEUR CHAMPIONSHIP? • For AH Match Play • by JOHN D. AMES USGA Vice-President and Chairman of Championship Committee HERE ARE MANY possible ways of con sional Golfers' Association for deciding its Tducting the USGA Amateur Cham annual Championship.) pionship, and many ways have been tested So in the Amateur Championship the since the start of the Championship in winner has always been determined at 1895. There have been Championship qual match play. The very first Championship, ifying rounds variously at 18, 36 and 54 in 1895, was entirely at match play, with holes, qualifying fields of 16, 32 and 64 no qualifying. Today, after many wander players, double qualifying at the Cham ings among the highways and byways of pionship site, all match play with a field of other schemes, the Championship proper is 210 after sectional qualifying. entirely at match play, after sectional qual Every pattern which seemed to have ifying at 36 holes. any merit has been tried. There is no gospel Purpose of the Championship on the subject, no single wholly right pat tern. Now what is the purpose of the Ama Through all the experiments, one fact teur Championship? stands out clearly: the Championship has Primarily and on the surface, it is to always been ultimately determined at match determine the Champion golfer among the play. Match play is the essence of the members of the hundreds of USGA Reg tournament, even when some form of ular Member Clubs. stroke-play qualifying has been used. But as much as we might like to believe The reason for this is embedded in the otherwise, the winner is not necessarily the original nature of golf. -

The Sport of Prince's Laddie Lucas Reflections of a Golfer

Born in the club house at the famous Prince's Golf Club, Sandwich, of which his father was the co-founder, Laddie Lucas was later to become a highly distinguished fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force during the second World War and a Member of Parliament. He also became a remarkably fine golfer and after captaining Cambridge and England he led Great Britain in the Walker Cup against the USA. In this unashamedly nostalgic book, the author describes his hobby of a lifetime - fifty years of pleasurable involvement in golf. He has been a friend or acquaintance of many of the great amateurs and pro fessionals of the period from Vardon, Ouimet and Ray to Henry Cotton and Jack Nicklaus. His perceptive pen portraits build up to form a delightful and wide ranging survey of golf since the First World War. Immersed in the game from such an early age - his nursery was the pro's shop - Laddie Lucas has not only an instinct for the game but a flair for assessing and expressing the qualities and technical skills of golfers he has observed. His analyses of some of the great golfers are particularly intriguing. In his concern for its expanding future, the author sets out new ways for the develop ment of golf as a less exclusive sport - with John Jacobs he has devoted much time over the years to the means of teaching young golfers and, as a member of the Sports Council, to widening the appeal of the game. Laddie Lucas, trained as a journalist, has picked out the features of a golfing lifetime from the standpoint of player, critic and administrator. -

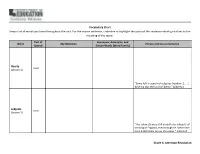

Vocabulary Chart Keep a List of Words You Learn Throughout the Unit. For

Vocabulary Chart Keep a list of words you learn throughout the unit. For the source sentence, underline or highlight the parts of the sentence which give clues to the meaning of the word. Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) liberty noun (Lesson 1) “Some left in search of religious freedom. [. .] America was the land of liberty.” (Liberty!) subjects noun (Lesson 1) “The colonists were still proud to be subjects of the king of England, even though he ruled them from 3,000 miles across the ocean.” (Liberty!) Grade 4: American Revolution Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) opportunity noun (Lesson 1) “But in America, if you worked hard, you might become one of the richest people in the land. [. .] they were very glad to live in the new and wonderful land of opportunity‐‐ America.” (Liberty!) ally noun (Lesson 1) “[The English settlers] had a powerful ally‐‐England. They called England the ‘Mother Country.’ [. .] Now that her children were in danger, the Mother Country sent soldiers to help the settlers’ own troops defend the colonies against their enemies.” (Liberty!) Grade 4: American Revolution Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) possession noun (Lesson 1) “France lost almost all her possessions in North America. Britain got Canada and most of the French lands east of the Mississippi.” (Liberty!) declaration noun (Lesson 3) “The Declaration of Independence, which was signed by members of the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, showed that the colonies wanted to be free.” (...If You Lived at the Time...) Grade 4: American Revolution Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) interested verb (Lesson 3) “Each colony was interested only in its local problems. -

Teeing Off for 1921 a Brief Glance at the Possible Features for the Coming Season on the Links by Innis Brown

20 THE AMERICAN GOLFER Teeing Off for 1921 A Brief Glance at the Possible Features for the Coming Season on the Links By Innis Brown IGURATIVELY speaking, the golfing lowing have signified a desire to join the on what the Britons are thinking and saying world is now teeing off for the good expeditionary force: Champion "Chick" of the proposal to send over a team. When F year 1921, though as a matter of fact a Evans, Francis Ouimet, "Bobby" Jones, Harry Vardon and Ted Ray arrived back moody, morose and melancholy majority is Davidson Herron, Max R. Marston, Parker home after their extended tour of the States, doing nothing more than casting an occasional W. Whittemore, Nelson M. Whitney, Regi- both Harry and Ted derived no little fun furtive glance in the direction of its links nald Lewis and Robert A. Gardner. It is from telling their friends among the ranks paraphernalia, and maligning the turn of probable that one or two others may be added of home amateurs just what lay in store for weather conditions that have driven it indoors to the above list. them, if America sent over a team. Both pre- for a period of hibernation. But that more This collection of stars will form far and claimed boldly that the time was ripe for fortunate, if vastly outnumbered element away the most formidable array of amateur Uncle Sam to repeat on the feat that Walter which is even now trekking southward, has talent that ever launched an attack against J. Travis performed at Sandwich in 1904, already begun to set the new golfing year when he captured the British title. -

Cyclopaedia 15 – Alternate History Overview

Cyclopaedia 15 – Alternate History By T.R. Knight (InnRoads Ministries * Article Series) Overview dimensions, or technological changes to explore these historical changes. Steampunk, Alternate History brings up many thoughts dieselpunk, and time/dimensional travel and feelings. To historical purists, this genre stories are good examples of this subcategory of fiction can look like historical revisionism. of Alternate History. Alternate History rides a Speculative fiction fans view these as “What fine line between Historical Fiction and If” scenarios that challenge us to think Science Fiction at this point. outside historical norms to how the world could be different today. Within the science Whatever type of Alternate History you fiction genre, alternate history can take on enjoy, each challenges your preconceived many sub-genres such as time travel, understandings and feelings for a time period alternate timelines, steampunk, and in history, perhaps offering you new dieselpunk. All agree that Alternate History perspectives on the people and events speculates to altered outcomes of key events involved. in history. These minor or major alterations Most common types of have ripple effects, creating different social, political, cultural, and/or scientific levels in Alternate History? the world. Alternate History has so many sub-genres Alternate History takes some queues from associated with it. Each one has its own Science Fiction as a genre. Just like Science unique alteration of history, many of which Fiction, Alternate History can be organized are considered genres or themes unto into two sub-categories that are “Hard” and themselves. “Soft” like Science Fiction. 80s Cold War invasion of United “Hard” Alternate History could be viewed as States stories and themes that stay as true to actual Axis victory in World War II history as possible with just one or two single Confederate victory in American changes that change the outcome, such as Civil War the Confederate Army winning the Civil War Dieselpunk or the Axis winning World War 2. -

Memorial's 2010 Honoree Award

MEMORIAL’S 2010 HONOREE AWARD BACKGROUND The Memorial Tournament was founded by Jack Nicklaus in 1976 with the purpose of hosting a Tournament in recognition and honor of those individuals who have contributed to the game of golf in conspicuous honor. Since 1996 and the Memorial’s inaugural honoree, Bobby Jones, the Event has recognized many of the game’s greatest contributors. PAST HONOREES 1976 Robert T. Jones, Jr. 1993 Arnold Palmer 2005 Betsy Rawls & 1977 Walter Hagen 1994 Mickey Wright Cary Middlecoff 1978 Francis Ouimet 1995 Willie Anderson – 2006 Sir Michael Bonalack – 1979 Gene Sarazen John Ball – James Charlie Coe – William 1980 Byron Nelson Braid – Harold Lawson Little, Jr. - Henry 1981 Harry Vardon Hilton – J.H. Taylor Picard – Paul Runyan – 1982 Glenna Collett Vare 1996 Billy Casper Densmore Shute 1983 Tommy Armour 1997 Gary Player 2007 Mae Louise Suggs & 1984 Sam Snead 1998 Peter Thomson Dow H. Finsterwald, Sr. 1985 Chick Evans 1999 Ben Hogan 2008 Tony Jacklin – Ralph 1986 Roberto De Vicenzo 2000 Jack Nicklaus Guldahl – Charles Blair 1987 Tom Morris, Sr. & 2001 Payne Stewart MacDonald – Craig Wood Tom Morris, Jr. 2002 Kathy Whitworth & 2009 John Joseph Burke, Jr. & 1988 Patty Berg Bobby Locke JoAnne (Gunderson) 1989 Sir Henry Cotton 2003 Bill Campbell & Carner 1990 Jimmy Demaret Julius Boros 1991 Babe Didrikson Zaharias 2004 Lee Trevino & 1992 Joseph C. Dey, Jr Joyce Wethered SELECTION Each year the Memorial Tournament’s Captain Club membership selects the upcoming Tournament honoree. The Captains Club is comprised of a group of dignitaries from the golf industry who have helped grow and foster the professional and amateur game. -

1950-1959 Section History

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1950 to 1959 Contents 1950 Ben Hogan won the U.S. Open at Merion and Henry Williams, Jr. was runner-up in the PGA Championship. 1951 Ben Hogan won the Masters and the U.S. Open before ending his eleven-year association with Hershey CC. 1952 Dave Douglas won twice on the PGA Tour while Henry Williams, Jr. and Al Besselink each won also. 1953 Al Besselink, Dave Douglas, Ed Oliver and Art Wall each won tournaments on the PGA Tour. 1954 Art Wall won at the Tournament of Champions and Dave Douglas won the Houston Open. 1955 Atlantic City hosted the PGA national meeting and the British Ryder Cup team practiced at Atlantic City CC. 1956 Mike Souchak won four times on the PGA Tour and Johnny Weitzel won a second straight Pennsylvania Open. 1957 Joe Zarhardt returned to the Section to win a Senior Open put on by Leo Fraser and the Atlantic City CC. 1958 Marty Lyons and Llanerch CC hosted the first PGA Championship contested at stroke play. 1959 Art Wall won the Masters, led the PGA Tour in money winnings and was named PGA Player of the Year. 1950 In early January Robert “Skee” Riegel announced that he was turning pro. Riegel who had grown up in east- ern Pennsylvania had won the U.S. Amateur in 1947 while living in California. He was now playing out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. At that time the PGA rules prohibited him from accepting any money on the PGA Tour for six months. -

Canadian Golfer, March, 1936

Lae @AnAaDIAN XXI No. 12 MARCH — 1936 OFFICIAL ORGAN ee Bobby Jones’ Comeback Page 19 Lhe ‘*BANTAM’’ SINGER 66 99 The latest from ENGLAND in the LIGHT CAR field Singer & Co. Ltd., were England’s pioneers in the light car world with the famous Singer “Junior”—a car which gained an unrivalled reputation for satisfactory performance and re- liability. Once again the Singer is in the forefront of modern design with this “Bantam” model. See them at our show room—they are unique in their class and will give unequalled service and satisfaction. All models are specially constructed for Canadian conditions. ..- FORTY (40) MILES TO THE GALLON ... When you buy a “Bantam” you buy years of troublefree motoring in a car that is well aheadof its time in design and construction ... Prices from $849.00. BRITISH MOTOR AGENCIES LTD. 22 SHEPPARD STREET TORONTO 2 CanaDIAN GOLFER — March, 1936 WILLCOX’S QUEEN OF WINTER RESORTS Canadian Golfer AIKEN,S.C. ‘ MARCH ° 1936 offers ARTICLES The Unfailing Sign—Editorial 3 Tracing a Golf Swing to A Family Tradition 5 By H. R. Pickens, Jr. A Bundle of Energy : 6 By Bruce Boreham A Rampartof the R.C.G.A. Structure 7 Go South, Young Golfers, Go South 8 By Stu Keate Feminine Fashion ‘Fore-Casts” 9 A SMALL English type Inn Those Very Eloquent Golfing Hands : 10 : ne - rs By H. R. Pickens, Jr. catering to the élite of the golf, polo and Be Brave in the Bunkers set. 11 e = Ontario Golf Ready to Go Forward 12 sporting world, more of a club than Looking Forward and Backward . -

1947-05-17 [P

Sanford Wins Again; Leafs Drop Buccaneers, 9-2 Sanford Edges 5-4 RAMBLERS FACE Tennis Club Battles ROWE REGISTERS Erratic Pirates Swept Victory Over Warsaw SOX ON SUNDAY Raleigh Here Today SIXTH VICTORY Off Feet By Smithfield Nessing Prove Big Guns In Jackets Play Bladenboro Raleigh’s powerful Eastern Caro- Here is an unofficial tentative Phil Vet Hasn’t Lost Yet; Corsairs On Nesselrode, lina Tenhis association netters col- lineup of today's matches: Carry Without Nate Andrews; In Eastern State court Mates Trounce Powerful Spinner Clin- lide with the new Wilmington Bob Andrew* vs. Bill Weathers, Reds Attack; on the Robert Poklemba Absent From Game Today aggregation today Horace Emerson vs. Ed Cloyle, By 8 4 Score Lineup; ton, Lumberton Win Strange clay courts at 3:00 p.m. Rev. Walter Freed vs. High If necessary, some matches will Kiger, Leslie Boney, Jr., vs. C. R. Play Sox Here BY JIGGS POWERS CINCINNATI, May 16.— {#) — Tonight take place on the asphalt at Green- Council, Gene Fonvielle vs. Father Joe Ness- Back by a 15-hit Nesselrode and While both and Two are booked in the field Lake. John Sloan vs. M. attack, Schoolboy j *fink Sanford Warsaw games Dillon, Jimmy Smithfield-Selma's Leafs sliced a that carried run Rowe boasted his sixth consecu- single in Eames. one-two home were the male side of Wil- W. in the men’s their Sanford’s battling it out, Lumberton Eastern State League for the com- Although Stubbs, singles. two-game series with the Wil- Benton, the out the star once tive victory, without a to- pitcher, grounded clayed roles waltzed to a mington tennis has proven slightly Other matches may be arranged. -

In the Right Direction How a Senior Knows New USGA Executive

In the Right Direction New USGA Executive After several unsuccessful attempts to play over a pond, a hapless golfer finally took a divot which flew over, leaving the ball behind. His caddie remarked: "That's better, sir. You got a bit of something over!" How A Senior Knows Miss Margaret Curtis, of Boston, who has never made any bones about the fact that she is 74 years old, got to talking about senior golf and senior golfers the other day and suddenly dipped into her handbag and produced the following, which she read with zest and feeling which only one in her seventies could apply to the subject: How do I know my youth has been spent? Because my get-up-and-gohas got up and went. But in spite of all that I am able to grin When I think where my get-up-and-gohas been. Old age is golden, I have heard it said But sometimes I wonder as I go to bed-- My ears in a drawer, my teeth in a cup, My eyes on the table until I get up- 'Ere sleep dims my eyes, I say to myself Robert C. Renner, of Pontiac, Mich., "15 there anything else I should lay on the shelf?" I am happy to say as I close the door joined the staff of the United States Golf My friends are the same as in days of yore. Association on September 1. He is serv- When I was young, my slippers were red, ing as a tournament executive, engaged I could kick my heels right over my head. -

Te Western Amateur Championship

Te Western Amateur Championship Records & Statistics Guide 1899-2020 for te 119t Westrn Amatur, July 26-31, 2021 Glen View Club Golf, Il. 18t editon compiled by Tim Cronin A Guide to The Guide –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Welcome to the 119th Western Amateur Championship, and the 18th edition of The Western Amateur Records & Statistics Guide, as the championship returns to the Glen View Club for the first time since the 1899 inaugural. Since that first playing, the Western Amateur has provided some of the best competition in golf, amateur or professional. This record book allows reporters covering the Western Am the ability to easily compare current achievements to those of the past. It draws on research conducted by delving into old newspaper files, and by going through the Western Golf Association’s own Western Amateur files, which date to 1949. A few years ago, a major expansion of the Guide presented complete year-by-year records and a player register for 1899 through 1955, the pre-Sweet Sixteen era, for the first time. Details on some courses and field sizes from various years remain to be found, but no other amateur championship has such an in-depth resource. Remaining holes in the listings will continue to be filled in for future editions. The section on records has been revised, and begins on page 8. This includes overall records, including a summary on how the medalist fared, and more records covering the Sweet Sixteen years. The 209-page Guide is in two sections. Part 1 includes a year-by-year summary chart, records, a special chart detailing the 37 players who have played in the Sweet Sixteen in the 63 years since its adoption in 1956 and have won a professional major championship, and a comprehensive report on the Sweet Sixteen era through both year-by-year results and a player register. -

Behind to Win Boat Battle Bent Razors

PAGE 8 THE INDIANAPOLIS TIMES .SEPT. 3, 1932 Talking WOOD COMES FROM BEHIND TO WIN BOAT BATTLE It Over to 132; BY DANIEL M. DANIEL New Yorkers Run String BRUSHING UP SPORTS byLaufer Yank Vet Editor's Note—flnrinr tho abufftro of Jor Milium*, on raration. this column l Bruins Seek 2 More Wins of Today brine rontrlbutrd h* Danlrl M. Danlrl Beats Don thr !*trw York-World Trleeram. YORK, Sept. 3.—Another ‘What of It?’ Queries Joe Chicago Hopes to Be First NEWnational championship tennis U. S. Speedboat Pilot Wins tournament at Forest Hills' The McCarthy, ‘We’ve Lost Baseball N. L. Team Since 1924 20-year-old “Slim" Vines of Cali- First Heat of Trophy fornia. defending the title against Games!’ AMERICAN ASSOCIATION Win the ebullient Henri Cochet and a Two Won. Lost. f'et. to .15. Race in Rain. with native Minneapolis *1 .VS .613 field which is impressive By 1 nilrd Press Columbus 78 64 .349 BY GEORGE KIRKSEY By nited strength and foreign threat. Some- NEW YORK, Sept. 3.—New York's INDIANAPOLIS 76 67 .332 United Press Staff Correspondent l Prf*# on Kansas City 74 66 .529 how these annual carnivals the Yankees have base- Milwaukee . 71 68 .511 Chicago LAKE ST. CLAIR, Mich.. Sept 3. most of 1932 joined CHICAGO. Sept. 3.—The Thf only y courts bring back memories by Toledo 71 73 .193 Gar Wood, American defender of ball's immortals playing 132 con- Louisville 35 86 .399 Cubs have an opportunity to create J who mo thf came x McLoughlin, vivid of Red St.