Samuel Hirsch and David Einhorn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Transformations in Jewish Self-Identification Before, During, and After the American Civil War" (2020)

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2020 Changing Notions of Identity: Transformations in Jewish Self- Identification Before, During, and After the American Civil War Heather Byrum Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History of Religion Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Byrum, Heather, "Changing Notions of Identity: Transformations in Jewish Self-Identification Before, During, and After the American Civil War" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1562. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1562 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Changing Notions of Identity: Transformations in Jewish Self-Identification Before, During, and After the American Civil War A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History from The College of William and Mary by Heather L. Byrum Accepted for _________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________ Carol Sheriff, Director Jay Watkins III Williamsburg, VA May 5, 2020 1 Changing Notions of Identity: Transformations in Jewish Self-Identification Before, During, and After the American Civil -

Coming to America…

Exploring Judaism’s Denominational Divide Coming to America… Rabbi Brett R. Isserow OLLI Winter 2020 A very brief early history of Jews in America • September 1654 a small group of Sephardic refugees arrived aboard the Ste. Catherine from Brazil and disembarked at New Amsterdam, part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. • The Governor, Peter Stuyvesant, petitioned the Dutch West India Company for permission to expel them but for financial reasons they overruled him. • Soon other Jews from Amsterdam joined this small community. • After the British took over in 1664, more Jews arrived and by the beginning of the 1700’s had established the first synagogue in New York. • Officially named K.K. Shearith Israel, it soon became the hub of the community, and membership soon included a number of Ashkenazi Jews as well. • Lay leadership controlled the community with properly trained Rabbis only arriving in the 1840’s. • Communities proliferated throughout the colonies e.g. Savannah (1733), Charleston (1740’s), Philadelphia (1740’s), Newport (1750’s). • During the American Revolution the Jews, like everyone else, were split between those who were Loyalists (apparently a distinct minority) and those who supported independence. • There was a migration from places like Newport to Philadelphia and New York. • The Constitution etc. guaranteed Jewish freedom of worship but no specific “Jew Bill” was needed. • By the 1820’s there were about 3000-6000 Jews in America and although they were spread across the country New York and Charleston were the main centers. • In both of these, younger American born Jews pushed for revitalization and change, forming B’nai Jeshurun in New York and a splinter group in Charleston. -

Extensions of Remarks E1301 HON. TED LIEU HON. CHARLES W

October 2, 2017 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1301 price. Habitat for Humanity’s ability to offer For nearly a century, PPL has continued to Among the clergy who followed in leading these goods and services at the ReStore is grow and expand. Today, PPL services nearly Har Sinai Congregation was Rabbi David made possible by the hard work of volunteers 10 million customers in central and eastern Philipson, an American-born scholar and theo- and donors throughout the community. By Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and the United King- logian who led the community from 1884 to working on behalf of their neighbors, the vol- dom. Furthermore, the company employs over 1888. A member of the first graduating class unteers of Habitat for Humanity continue to 13,000 people. of the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, he enrich the North Country community. PPL has demonstrated itself as an impres- would go on to become one of the most On behalf of New York’s 21st District, I want sive business, based not only on its commit- prominent Reform rabbis of his age, authoring to thank Habitat for Humanity and its volun- ment to the greater Lehigh Valley and Penn- books on history, theology, and literature while teers for providing an invaluable service to the sylvania’s 15th District, but also on its commit- speaking out against anti-Semitism and, in his North Country. We are grateful for Habitat for ment to its employees. The FUSE business later years, the rise of Nazism. Today, the Humanity’s commitment to this region, and resource group is a shining example of this congregation is led by Rabbi Linda Joseph, a look forward to the benefits that the ReStore commitment. -

Download Date 27/09/2021 07:10:13

Isaac Mayer Wise: Reformer of American Judaism Item Type Electronic Thesis; text Authors Tester, Amanda Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 07:10:13 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/144992 Tester 1 Introduction From the time that Jews first settled in North America, American Judaism developed on a different course than that of European Judaism. Jews in the United States were accepted and acculturated into mainstream society to a higher degree than their European counterparts. They lived in integrated communities, did business with Christians and Jews alike, and often sent their children to secular schools. After the United States became independent and broke some of its close European ties, many American Jews began to follow Jewish rituals less closely and attend synagogue less often than their European forbears, both because of an economic need to keep business on the Christian calendar and because of a lack of Jewish leadership in the United States that would effectively forbid such practices.1 Religious bonds and communities were not as tight knit as had been the case in Europe; American Judaism had no universally accepted religious authority and -

The Theology of Redemption in Contemporary American Reform Liturgy

The Theology of Redemption in Contemporary American Reform Liturgy Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies David Ellenson, Ph.D., Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies by Neal Gold May 2018 Copyright by Neal Gold © 2018 Acknowledgments As I submit this thesis, I realize how grateful I am to all the individuals who have shaped my thinking and my perspectives. Dr. David Ellenson has been much more than a thesis advisor; indeed, it was Dr. Ellenson’s sage counsel and encouragement that brought me to Brandeis in the first place. I am profoundly grateful for the ‘eitzah tovah that he has provided for me, and I am humbled and grateful that my time at Brandeis coincided with his serving as Director of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies. Likewise, Dr. Yehudah Mirsky, who served as second reader, has been much more than that; his lessons have provided the sort of intellectual exploration I was looking for in my return to graduate school. I am grateful to call him my teacher. The NEJS Department at Brandeis is an exhilarating place, filled with extraordinary scholars, and I feel a special bond and debt of gratitude to every one of my teachers here. My family always has been a source of love, support, and enthusiastic affection during these strange years when Dad decided to go back to school. Avi and Jeremy have taken all this in stride, and I pray that, through my example, they will incorporate the serious intellectual study of Judaism throughout their own lives, wherever their paths may take them. -

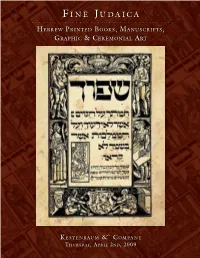

Fi N E Ju D a I

F i n e Ju d a i C a . he b r e w pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , Gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a l ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , ap r i l 2n d , 2009 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 38 Catalogue of F INE JUDAICA . PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS, AUTOGRAPH LETTERS, CEREMONIAL & GRAPHIC ART Including: The Prague Hagadah, 1526 An Extraordinarily Fine Copy of Abraham ibn Ezra’s Commentary to the Torah, Naples, 1488 An Autograph Manuscript Signed by R. Yonassan Eybescheutz Governor Worthington’s Speech on the Maryland Test Act, Baltimore, 1824 Photographic Archive by Issacher Ber Ryback Selections from the Rare Book-Room of a College Library (Final Part) (Short-Title Index in Hebrew available upon request) ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 2nd April, 2009 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on: Sunday, 29th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Monday, 30th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 31st March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 1st April - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Thursday, 2nd April - 10:00 am - 2:30 pm Gallery-Talk with the Auction Expert: Tuesday, 31st March at 6:00 pm This Sale may be referred to as: “Merari” Sale Number Forty-Three Illustrated Catalogues: $35 (US) * $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . -

Transcript: Peering Into the Past Podcast Written, Recorded, Edited

Transcript: Peering Into the Past Podcast written, recorded, edited and transcribed by JMM intern Marisa Shultz. Hello, and welcome to the first and only episode of Peering into the Past. I am your host, Marisa Shultz, Education and Programs intern at the Jewish Museum of Maryland, and I am delighted that you have decided to join me today. Today we are going to be learning about a fascinating and somewhat forgotten portion of American Antebellum history: Jewish perspectives on slavery and abolitionism. In the Civil War field, we often discuss how preachers from various protestant congregations used their pulpit to share their views on the hot-button issue of the time, but we often forget to acknowledge that there were Jews living in the United States, and that many of them would fight during the Civil War on both sides of the battlefield. Today we’re going to start by talking about the different positions people had on slavery and a general overview of some of the most outspoken Antebellum Jewish figures. Then we will look specifically at two Rabbis on opposite sides of the argument who both served in Baltimore, Maryland. Perspectives on slavery are often grouped into three broad categories: Abolitionism, anti- slavery, and pro-slavery; these positions exist on a spectrum, with pro-slavery on one side, Abolitionism on the other, and anti-slavery somewhat in the middle. I would like to start by clearing up some confusion I often see about these terms, namely I would like to highlight the difference between Abolitionism and anti-slavery. -

LINCOLN and the JEWS ISAAC MARKENS Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (1893-1961); 1909; 17, AJHS Journal Pg

LINCOLN AND THE JEWS ISAAC MARKENS Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (1893-1961); 1909; 17, AJHS Journal pg. 109 LINCOLN AND THE JEWS. By ISAAC MARKENS. Since the name of Abraham Lincoln has been linked with no stirring event in connection with American Judaism it follows that the subject" Lincoln and the Jews," may possibly be lacking in the essentials demanding treatment at the hands of the critical historian. Nevertheless, as a student of the great war President the writer has been impressed by the vast amount of interesting material bearing upon his relations to the Jews. which it occurs to him is worthv of comnilation and preservation. A contribution of this character seems specially fitting at the present time in view of the centenary of the one whose gaunt figure towers above aU others in the galaxy of American heroes-" the first of our countrymen to reach the lonely heights of immortal fame." The Jews of the United States formed but a small portion of the population in Lincoln's time. The President of the Board of Delegates of American Israelites, their representa~ tive organization, estimated their number in the loyal States near the close of 1861 at not less than 200,000, which figures are now regarded as excessive. The Rev. Isaac Leeser as late as 1865 could not figure the entire Jewish population of the United States as exceeding 200,000, although he admitted that double that number had been estimated by others. Political sentiment was then divided and found expression largely through the Occident, a monthly, published by Rev. -

Rabbi Seth M. Limmer: Politics in Judaism and Judaism in Politics

RABBI SETH M. LIMMER: POLITICS IN JUDAISM AND JUDAISM IN POLITICS (Begin audio) Joshua Holo: Welcome to the College Commons podcast, passionate perspectives from Judaism's leading thinkers, brought to you by the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, America's first Jewish institution of higher learning. My name is Joshua Holo, Dean of HUC's Jack H Skirball campus in Los Angeles, and your host. You're listening to a special episode recorded at the URJ Biennial in December of 2019. JH: Welcome to the College Commons podcast, and this episode with Rabbi Seth M Limmer. Rabbi Limmer serves as senior rabbi of Chicago Sinai congregation, and he has served as Chair of the Justice, Peace and Civil Liberties Committee of the central conference of American Rabbis. On behalf of Chicago Sinai congregation's lead role in organizing the Reform movement's participation in the NAACP's 2015 America's Journey for Justice, Rabbi Limmer accepted the Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath Bearer of Light Award, which is the highest honor bestowed by the URJ. In 2016, he authored Medieval Midrash: The House for Inspired Innovation. And being a medievalist myself, it is a great pleasure to welcome you, Rabbi Limmer, to the College Commons podcast. Rabbi Seth M Limmer: Thanks, pleasure to be here. JH: Among your many sermons which touch on a wide variety of really cool topics... RL: Thanks. JH: You offered one about the decision in Chicago Sinai to set up, in permanent fashion, national flags in the temple space. For many of our listeners, the mere fact that that would have been: A, that they wouldn't have been there already; and B, that it was a question, is news. -

This Week in Torah Ki Teitse Rabbi Matt Cutler 8.26.20 There Is a Lot of Revisiting of Slavery in Our History. the 13Th Amendmen

This Week In Torah Ki Teitse Rabbi Matt Cutler 8.26.20 There is a lot of revisiting of slavery in our history. The 13th amendment was added to the Constitution in 1865 [which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude], but it did not rid America of racism. There are many who would argue that the enslavement of black Americans was replaced with Jim Crow laws, segregation, and a higher percentage of minority incarceration. Check out the documentary “13th” on Netflix. Worldwide—human trafficking is a tremendous problem that affects every continent in the world: women forced into the degrading and dangerous life of sex trafficking, Africans kidnapped to work in neighbor countries on plantations, Asians caught up into indentured servitude—just to name a few. These memories are more than just personal; they become communal as they are etched into the psyches of numerous people. We as Jews understand this—over and over again [including this parasha]; we are told in Torah to remember that we were slaves in Egypt. It is true that Torah law does permit slavery; it is a travesty we need to acknowledge. Yet Torah law does have a remedy to it-- purchase price of one's freedom and emancipation in the Jubilee year as well as the ethics of the treatment of slaves that were introduced to ensure that they were created in the image of God was not forgotten. The morality and legality of slavery were argued through Jewish history and most poignantly, in the 19th century—prominent rabbis like David Einhorn spoke vehemently against it from his pulpit in Philadelphia and others like Rabbi Morris David Raphall spoke of its permissibility from his pulpit in New York City.