Conseg ^ F Denial Uences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia: CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 to FEBRUARY 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper RUSSIA CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 TO FEBRUARY 1995 July 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures Political Leaders 1. INTRODUCTION 2. CHRONOLOGY 1993 1994 1995 3. APPENDICES TABLE 1: SEAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE STATE DUMA TABLE 2: REPUBLICS AND REGIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION MAP 1: RUSSIA 1 of 58 9/17/2013 9:13 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... MAP 2: THE NORTH CAUCASUS NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures [This glossary is included for easy reference to organizations which either appear more than once in the text of the chronology or which are known to have been formed in the period covered by the chronology. The list is not exhaustive.] All-Russia Democratic Alternative Party. Established in February 1995 by Grigorii Yavlinsky.( OMRI 15 Feb. -

The First Armenia-Diaspora Conference Ends with High Expectations

.**" >■; -.' "****<*^. :■.: » ■:l Process The First Armenia-Diaspora Conference Ends with High Expectations By SALPI HAROUTINIAN GHAZARIAN; Photos by MKHITAR KHACHATRIAN The most important thing that came Armenians from Belarus to Brazil to articulate Diaspora relations. Seated around a large circle out of the first Armenia-Diaspora their vision of the Armenia-Diaspora lelationship. of tables were the representatives of the small Conference, held September 22-23 The third most important thing was that est and largest Diaspora communities, as well in Yerevan, was that it happened at Diasporans who participated in the Conference as the republic's leadership. The president and all. Many were the skeptics from came to realize that the government is serious the prime minister, the head of parliament and Armenia and Irani the dozens of par about developing, fine-tuning and institu the chairman of Armenia's Constitutional ticipating countries who admitted that they tionalizing an ongoing process of Armenia Court, were present for most of the two-day didn't believe the government could pull off a meeting. In the mornings, they addressed the massive organization ei'i'ort such as this participants; the remainder of the time, they turned out to be. Equally doubtful was listened to representatives of 59 delegations, whether the Diaspora would respond. But each representing one country or geographic unlike most conferences, almost all of those area. There were also statements by the leader who were invited actually came. Over 1,000 ship of major international institutions from people participated either as members of churches and political parties to the Armenian regional delegations, or as invited individuals General Benevolent Union, the Armenia Fund in this llrst-of-its-kind international conclave. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

2018 Mentoring Fair Biographies

The Women’s Foreign Policy Group and The George Washington University Career Center 2018 Mentoring Fair Biographies Lieutenant Colonel Ariel Batungbacal - United States Air Force Ms. Batungbacal is a Lieutenant Colonel in the US Air Force, and is a student at the National War College. She has served extensively overseas, supporting military operations in Asia, Europe and the Middle East. She is a term member of the Council of Foreign Relations, and previously served as a Southern California Leadership Network Fellow, and a Junior League Board Fellow. She received an Executive Master’s in Leadership from Georgetown University, an MA in Diplomacy from Norwich University, a BA in Chinese and BA in Government/Politics from the University of Maryland, College Park. Gretchen Bloom - World Food Programme's Alumni Network Ms. Bloom has over 40 years of experience in international development and humanitarian assistance, beginning as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Togo. She is currently a Gender Expert for the World Food Programme's Alumni Network. Ms. Bloom has worked, lived and traveled in 100 countries, where she focused primarily on gender issues. She worked as the Gender Adviser in the ANE Bureau of USAID before joining the UN World Food Programme as the Senior Gender Adviser. She retired from WFP after serving 15 months in Kabul, Afghanistan. Since 2003, she has worked as a Gender Expert for WFP, USAID, DFID and the World Bank. Her interest in gender began when she earned her Master's degrees in sociology and community health in New Delhi at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Nancy Boswell - American University Washington College of Law Ms. -

Genocide Bibliography

on Genocide The Armenian Genocide A Brief Bibliography of English Language Books Covering Four Linked Phases Genocide Facts Presentation of Oral and Written Evidence for the Armenian Genocide in the Grand Committee Room, The House of Commons London 24th April 2007 First and Second Editions 2007, with Addenda 2009, Third Edition 2011, Fourth Edition 2013, Fifth Edition Centennial Presentation, the 1st of January, 2015 Sixth Edition © English By Français T.S. Kahvé Pусский Español Ararat Heritage Հայերեն London Português 2017 Genocide: Beyond the Night, by Jean Jansem, detail photography by Ararat Heritage PREFACE There are certain polyvalent developments of the past that project prominently into the contemporary world with pertinent connotations for the future, decisively subsuming the characteristics of permanence. Their significance dilates not only because well organised misfeasance bars them from justice, but also because of sociological and psychological aspects involving far-reaching consequences. In this respect, the extensive destruction brought about by the Armenian Genocide and the substantive occupation of Armenia’s landmass by its astonishingly hostile enemies will remain a multifarious international subject impregnated with significant longevity. Undoubtedly, the intensity of the issue in motion will gather momentum until a categorically justifiable settlement is attained. A broad reconstruction programme appears to be the most reasonable way forward. PREAMBLE 1st. PRELUDE TO GENOCIDE Encompasses the periods referred to as the Armenian Massacres; mainly covering the years 1894 - 96 and Adana 1909. Some titles in the bibliography record the earlier international treaties that failed to protect the Armenians. Only a small number of works have been included, predominantly relevant to this period. -

Exclusiveparliamentary Elections: Armenia at 25

EXCLUSIVE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS: ARMENIA AT 25 FACES THE FUTURE P.20 ARMENIAN GENERAL BENEVOLENT UNION FEB. 2017 The Promise Overcoming the obstacles as epic story of survival and compassion starring Christian Bale and Oscar Isaac hits theaters April 21 Armenian General Benevolent Union ESTABLISHED IN 1906 Central Board of Directors Հայկական Բարեգործական Ընդհանուր Միութիւն President Mission Berge Setrakian To preserve and promote the Armenian heritage through worldwide educational, cul- Vice Presidents tural and humanitarian programs Sam Simonian Sinan Sinanian Annual International Budget Treasurer Forty-six million dollars (USD) Nazareth A. Festekjian Assistant Treasurer Education Yervant Demirjian 24 primary, secondary, preparatory and Saturday schools; scholarships; alternative edu- Secretary cational resources (apps, e-books, AGBU WebTalks & more); American University of Armenia; Armenian Virtual College (AVC); TUMO x AGBU Sarkis Jebejian Assistant Secretary Cultural, Humanitarian and Religious Arda Haratunian AGBU News Magazine; the AGBU Humanitarian Emergency Relief Fund for Syrian Honorary Member Armenians; athletics; camps; choral groups; concerts; dance; films; lectures; leadership; His Holiness Karekin II, library research centers; medical centers; mentorships; music competitions; publica- Armenia: Catholicos of all Armenians tions; radio; scouts; summer internships; theater; youth trips to Armenia. Members Holy Etchmiadzin; Arapkir, Malatya and Nork Children’s Centers and Senior Dining UNITED STATES Centers; Hye Geen Women’s -

Armenian Voice No

22177 V2.qxp_AVoice 52-latest1 02/08/2018 09:55 Page 1 ARMENIAN CENTRE FOR ARMENIAN INFORMATION VOICE AND ADVICE NEWSLETTEr for THE LoNdoN -ArmENIAN CommUNITy. SPrING 2018 No.71 PUbLISHed by THe CeNTRe FoR ARmeNIAN INFoRmATIoN ANd AdvICe (RegISTeRed CHARITy 1088534 & A LImITed ComPANy No. 4195084) ‘HAyASHeN’,,105A mILL HILL RoAd, ACToN, LoNdoN W3 8JF. TeLePHoNe 020-8992 4621. E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.caia.org.uk facebook: www.facebook.com/Hayashen THe WoRK oF CAIA IS SUPPoRTed by vARIoUS CHARITIeS & THe LoNdoN boRoUgH oF eALINg - NeWSLeTTeR PUbLISHed SINCe 1987 The UK Armenians & WW1 project accomplished its objectives earlier this year by producing/displaying its exibition and accompanying film several times in London and Manchester. We are grateful to everyone who contributed to this project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. (Read more inside this newsletter) CAIA LAUNCHES NEW WEBSITE The CAIA is pleased to announce that it has launched its new website produced by Tatevik Ayvazyan supported by Diane John which now incorporates information about its diverse services, projects and archives. While there are some final touches to be made , you can view the website at www.caia.org.uk as well find out more about The UK Armenians & WW1 project research/archives, where you can watch the film, Testimonies of War. n CAIA is proud to announce that during May 2018 a series of CONDOLENCES refurbishments were successfully carried out to improve the experience of people visiting Hayashen thanks to support from benefactor Gagik Tsarukyan, The National Lottery Awards for All, It is with deep sorrow that CAIA announces the passing of two and The London Legal Support Trust. -

E-Newsletter Volume 3, Issue 20

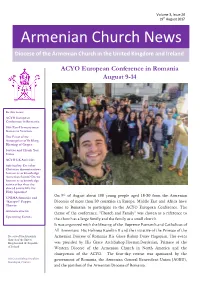

Volume 3, Issue 20 19th August 2017 Armenian Church News Diocese of the Armenian Church in the United Kingdom and Ireland hurchACYO European News Conference in Romania August 9-14 In this issue: ACYO European Conference in Romania 10th Pan-Homenetmen Games in Yerevan The Feast of the Assumption of St Mary, Blessing of Grapes Service and Thank You Notes ACYO UK Activities Spirituality: Do other Christian denominations honour or acknowledge Armenian Saints? Do we honour or acknowledge saints other than the shared saints like the Holy Apostles? On 9th of August about 100 young people aged 18-30 from the Armenian UNIMA -Armenia and “Karapet” Puppet Dioceses of more than 30 countries in Europe, Middle East and Africa have Theatre come to Romania to participate in the ACYO European Conference. The Announcements theme of the conference, "Church and Family" was chosen as a reference to Upcoming Events the church as a large family and the family as a small church. It was organized with the blessing of the Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians His Holiness Karekin II and the initiative of the Primate of the Diocese of the Armenian Armenian Diocese of Romania His Grace Bishop Datev Hagopian. The event Church of the United Kingdom and the Republic was presided by His Grace Archbishop Hovnan Derderian, Primate of the of Ireland Western Diocese of the Armenian Church in North America and the chairperson of the ACYO. The four-day retreat was sponsored by the His Grace Bishop Hovakim government of Romania, the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), Manukyan, Primate and the parishes of the Armenian Diocese of Romania. -

Report on the Findings About Translations from Armenian to Swedish

Translations from Armenian into English, 1991 to date a study by Next Page Foundation in the framework of the Book Platform project conducted by Khachik Grigoryan1 September 2012 1 Khachik Grigoryan is a publisher. This text is licensed under Creative Commons Translations from Armenian into English, 1991 to date Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 "Golden age" of Armenian literature ............................................................................................ 2 Further development of Armenian literature ............................................................................ 3 A historical overview of translations from Armenian ............................................................... 4 Modern Armenian literature .......................................................................................................... 7 Translations into English during Soviet period (1920-1991) .................................................... 8 Armenian literature after the Karabagh movement and Independence 1988- .................... 9 Armenian translations in the UK market ..................................................................................... 9 Structure of translated books from Armenian into English .................................................... 12 Policy and support for translations ............................................................................................ 13 -

“If I Die, I Die”: Women Missionary Workers Among Danes, Armenians, and Turks, 1900-19201

“IF I DIE, I DIE”: WOMEN MISSIONARY WORKERS AMONG DANES, ARMENIANS, AND TURKS, 1900-19201 Matthias Bjørnlund Based on extensive studies of archival material and little-known contemporary published sources, this article will explore how and why Danes – famous in certain circles like Maria Jacobsen, virtually unknown like Hansine Marcher and Jenny Jensen, but all women – ended up in remote corners of the Ottoman Empire before and during the Armenian Genocide. They were sent out as field workers for one of the world’s first proper NGOs, the Danish branch of the Evangelical organization Women Missionary Workers. What did these women from the European periphery experience, and how were they perceived at home and abroad during peace, war, massacre, and genocide? Why did the Armenians among all the suffering peoples of the world become their destiny, even after the genocide? And how did they try to make sense of it all, from everyday life and work before 1915 to the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians and the immediate aftermath? The article will put the missionary and experiences into an ideological, institutional, local, regional, and international context, and consider to what extent the Danish women could be considered feminist and humanitarian pioneers. Key-words: Armenian genocide, missionaries, humanitarianism, gender studies, Christian millenarianism, Armenophilia, Middle East, Turkey, Ottoman Empire. 1. This paper is based to a large extent on heavily edited and updated parts of my two monographs in Danish: Matthias Bjørnlund, Det armenske folkedrab fra begyndelsen til enden (Copenhagen: Kristeligt Dagblads forlag, 2013) (The Armenian Genocide from the Beginning to the End), and idem, På herrens mark: Nødhjælp, mission og kvindekamp under det armenske folkedrab (Copenhagen: Kristeligt Dagblads Forlag, 2015) (In God’s Field. -

Monuments and Memory: the Remediation and the Visual Appropriations of the Mother Armenia Statue on Instagram During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

Monuments and Memory: The Remediation and the Visual Appropriations of the Mother Armenia Statue on Instagram During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War Lala Mouradian A Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Media Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2021 © Lala Mouradian, 2021 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Lala Mouradian Entitled: Monuments and Memory: The Remediation and the Visual Appropriations of the Mother Armenia Statue on Instagram During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Media Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: ______________________________________Chair Dr. Jeremy Stolow ______________________________________ Examiner Dr. Stefanie Duguay ______________________________________ Examiner Dr. Jeremy Stolow ______________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Monika Gagnon Approved by________________________________________________ Dr. Monika Gagnon Chair of Department ________________________________________________ Dr. Pascale Sicotte Dean of Faculty Date: April 9, 2021 Abstract Monuments and Memory: The Remediation and the Visual Appropriations of the Mother Armenia Statue on Instagram During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War Lala Mouradian This thesis analyzes the remediation and the visual appropriations of the Mother Armenia statue on Instagram during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. The Mother Armenia statue was erected in 1967 in Armenia’s capital city of Yerevan as a female personification of Armenia. Its meaning and symbolism have been reworked during different collective crises for the Armenian nation. -

The Armenian Massacres of 1894-1897: a Bibliography

The Armenian Massacres of 1894-1897: A Bibliography © George Shirinian, Revised August 15, 1999 Introduction The large-scale and widespread massacres of the Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire, from Sasun in August 1894 to Tokat in February and March 1897, caused a sensation in Europe and North America. They gave rise to a flood of publications detailing numerous atrocities and expressing moral outrage. Modern scholarship, however, has tended to overlook this series of massacres and concentrate on the 1915 Armenian Genocide, owing to its very enormity. Since works on the 1894-1897 massacres are generally not as well known today as those on the subsequent Genocide, this bibliography attempts to document these publications and organize them into useful categories. The Armenian Massacres of 1894-1897 are very complex and have been approached from various points of view. Writers have attributed their outbreak to many causes, e.g., 1. the lack of civil and human rights for the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, resulting in systemic abuse of all kinds; 2. Kurdish depredations; 3. Armenian reaction to outrageous taxation; 4. the failure of the Congress of Berlin, 1878, to properly address the Armenian Question; 5. The Congress of Berlin for even attempting to address the Armenian Question; 6. Armenian intellectuals engendering in the people a desire for independence; 7. the successful efforts of other nationalities to extricate themselves from the Ottoman Empire; 8. manipulation of the naive Armenians to rebel by the Great Powers interested in partitioning the Ottoman Empire; 9. manipulation of the European Powers by the calculating Armenians to become involved in internal Ottoman affairs on their behalf; 10.