United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parole in Conflitto

PAROLE IN CONFLITTO 20 anni di narrazione del conflitto israelo- palestinese sui quotidiani italiani Introduzione Il conflitto israelo-palestinese è, sin dal suo scoppio, uno dei temi più trattati dai media occidentali; con una cadenza costante, che diventa quotidiana durante le frequenti fasi di crisi, Palestina e Israele entrano nelle nostre vite attraverso le immagini trasmesse dalla televisione, le analisi radiofoniche, i lunghi articoli stampati sui giornali. Questo estremo interesse nei confronti di questo specifico conflitto è dovuto a diversi fattori, in primis, la sua durata: a 68 anni dal suo inizio, che si usa far corrispondere al 1948, anno del riconoscimento dello Stato di Israele, benché l’incipit del processo possa essere fatto risalire alla fine dell’800, esso può essere considerato il più lungo della storia contemporanea. L’importanza geopolitica dell’area mediorientale, della quale Palestina e Israele fanno parte, ha rivestito durante il ‘900 e riveste tutt’ora un ruolo fondamentale nello scacchiere economico mondiale per la presenza di risorse petrolifere e gas naturali, responsabili dell’instabilità dell’intera area a causa del tentativo di influenza su di essi da parte delle potenze mondiali. Si aggiungano a questi altri fattori: religiosi, dovuti al forte legame tra questo piccolo territorio (27,000 km2) e il cristianesimo; culturali, legati a migliaia di anni di contatti nel bacino mediterraneo; etnici, in quanto gli israeliani vengono percepiti dal pubblico come europei bianchi, per i quali viene sentita un’empatia da parte occidentale, che va a sommarsi alla paura del “diverso”, in particolare se “arabo”, acuitasi dopo il crollo delle Torri Gemelle del 2001. -

Honor Killings" Triggers Palestinian Calls for Cultural Changes, New Laws

Bulletin – July 1, 2012 PA: Israel spreads drugs to destroy Palestinian society by Itamar Marcus and Nan Jacques Zilberdik One day after Iranian Vice President Mohammad-Reza Rahimi was condemned internationally for saying that Jews and their Talmud are responsible for international drug trafficking, no less than five articles in the official PA daily cited different Palestinian Authority officials accusing Israel of having a policy to disseminate drugs among Palestinian youth. The Governor of Jericho said that Israel "is encouraging and turning a blind eye to [drug] dealers and their efforts to distribute drugs, through a systematic policy to destroy Palestinian society, targeting the youth." The District Governor of Jenin said Israel "seeks to harm the Palestinian people and to destroy it and its national enterprise [through drugs] as a continuation of its Zionist enterprise." The District Governor of Ramallah spoke about the drug problem, mentioning Israel's "efforts to humiliate our youth, to break their willpower, and to distance them from their [Palestinian] cause and their principles, by spreading drugs among them" and emphasized that "the occupation does not hesitate to exercise all forms of control over our youth, using dirty and inhuman methods." This is not the first time that Israel has been accused by the PA of intentionally spreading drugs. Advisor to Prime Minister Salam Fayyad has claimed that Israel "spreads prostitution and drugs" among Arab residents of Jerusalem. [PA TV (Fatah), June 23, 2010] The PA has also accused Israel of spreading AIDS among Palestinians: Similarly, at a seminar about drugs organized by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the head of the Palestinian Authority's drug fighting agency said: "This plague [AIDS] is a political problem which is nurtured by Israel." [Al-Hayat Al-Jadida, June 24, 2010] The official PA daily reported that a Health Ministry official blamed Israel for the spread of AIDS among Palestinians: "Director of Public Health in the Health Ministry, Dr. -

Page 01 Feb 12.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Home | 2 Business | 21 Sport | 31 H H Sheikha Moza bint Qatar Exchange logged Qatar sports star Nasser Nasser officially opened its longest winning Saleh Al Attiyah has been Qatar Biobank’s new streak in the year by elected as a member of facility at Hamad Bin extending the rally to ISSF Athletes Committee Khalifa Medical City. eighth straight session. for a four-year period. THURSDAY 12 FEBRUARY 2015 • 23 Rabial II 1436 • Volume 19 Number 6339 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 OPINION SCH warns of Emir meets Iraq President Unity against Boko Haram action against HE danger of Boko Haram is no longer con- Tfined to Nigeria as this organisation is actively involved in terror- Seha misuse ist acts in many neigh- Expats to be covered by end of 2016 bouring countries. DOHA: The Supreme Council manipulate the system. The fraud It has of Health (SCH) has warned was detected while the company become the public and health care was conducting regular audits on a threat providers against misuse of invoices. One case has already not only the national health insurance been referred to the SCH and to the Dr Khalid Al Jaber scheme (Seha) saying it has reports about the second and security detected three cases of sus- third cases are being prepared. and stability of the African pected fraud until now. If the SCH investigation con- continent but the entire world. The National Health Insurance firms a violation of the law, action Boko Haram is the African Company (NHIC) managing Seha will be taken immediately including The Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani with President of the Republic of Iraq, Dr Fuad Masum, at the affiliate of Al Qaeda like the has launched a campaign “Kun closure of the facility or other legal Emiri Diwan yesterday. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

Freeing Gilad Shalit: the Cost to Israel | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 1859 Freeing Gilad Shalit: The Cost to Israel by David Makovsky Oct 13, 2011 ABOUT THE AUTHORS David Makovsky David Makovsky is the Ziegler distinguished fellow at The Washington Institute and director of the Koret Project on Arab-Israel Relations. Brief Analysis Although the Shalit deal may help Netanyahu, the massive prisoner release will backfire on him if there is a spate of terrorist attacks. n Tuesday, Israel and Hamas announced a two-phase prisoner exchange that would secure the release of O Sgt. Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier kidnapped in 2006 and held for more than five years in Gaza. In return, Israel would release 1,027 prisoners, including 280 who are serving life sentences for their involvement in terrorist acts. The deal was initially mediated by Gerhard Conrad, a senior German official with expertise in the Middle East who has overseen prisoner swaps between Israel and Hizballah since the 1990s. But it was Egyptian intelligence chief Maj. Gen. Murad Muwafi who played the pivotal role in recent weeks. According to reports of the deal, Israel will first release the most controversial 450 prisoners, in exchange for which Hamas will hand over Shalit to Egypt. Israel will then choose an additional 550 or so ostensibly non-Hamas prisoners for release. The group's leader -- Khaled Mashal, based in Damascus -- has reported that the first release will occur within a week and the second within two months. After on-and-off negotiations since Shalit's capture, new circumstances have apparently made a deal possible. The Calculations of Hamas R ecently, Hamas has watched Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas, the leader of its rival, Fatah, enjoy an enormous domestic boost as a result of his UN statehood bid. -

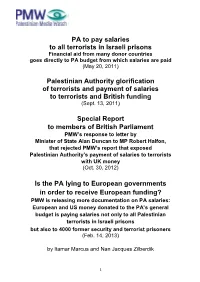

PA Salaries to Terrorists

PA to pay salaries to all terrorists in Israeli prisons Financial aid from many donor countries goes directly to PA budget from which salaries are paid (May 20, 2011) Palestinian Authority glorification of terrorists and payment of salaries to terrorists and British funding (Sept. 13, 2011) Special Report to members of British Parliament PMW’s response to letter by Minister of State Alan Duncan to MP Robert Halfon, that rejected PMW’s report that exposed Palestinian Authority’s payment of salaries to terrorists with UK money (Oct. 30, 2012) Is the PA lying to European governments in order to receive European funding? PMW is releasing more documentation on PA salaries: European and US money donated to the PA’s general budget is paying salaries not only to all Palestinian terrorists in Israeli prisons but also to 4000 former security and terrorist prisoners (Feb. 14, 2013) by Itamar Marcus and Nan Jacques Zilberdik 1 May 20, 2011 PMW Special Report: PA to pay salaries to all terrorists in Israeli prisons Financial aid from many donor countries goes directly to PA budget from which salaries are paid by Itamar Marcus and Nan Jacques Zilberdik A law published in the official Palestinian Authority Registry last month grants all Palestinians and Israeli Arabs imprisoned in Israel for terror crimes a monthly salary from the PA. The Arabic word the PA uses for this payment is "ratib," meaning "salary." Palestinian Media Watch has reported numerous times on Palestinian Authority glorification of terrorists serving time in Israeli prisons. Following the signing of this new law, the PA is now paying a salary to these prisoners. -

Jewish Journal Creates Endowment Fund by Michael Wittner JOURNAL STAFF

FEBRUARY 21, 2019 – 16 ADAR 5779 JEWISHVOL 43, NO 14 JOURNALJEWISHJOURNAL.ORG Jewish Journal creates endowment fund By Michael Wittner JOURNAL STAFF The Jewish Journal, the largest free Jewish publication in New England, has established an endowment to ensure its future. The newspaper plans to raise $500,000 in the next five years. “As a community and as stewards of this paper, we must make sure that this publication will continue to link Greater Boston Jewry,” said Steven Temple Emanu-El of Marblehead has a $2 million renovation fund. A. Rosenberg, the Journal’s publisher and editor. Bob Rose, a former president of the North Shore Jewish institutions Journal’s Board of Overseers, believes the Journal will find creative ways Neil Donnenfeld, president of the to navigate the ever-changing land- Jewish Journal Board of Overseers investing for the future scape for small community news- made a pledge to put $10,000 in my papers. That is why he and his wife estate planning for this fund, is that I By Michael Wittner Synagogues and Money.” However, Judson Martha donated $20,000 to start the don’t know what the future’s going to JOURNAL STAFF noted that in recent years, synagogues – like Jewish Journal Continuity Fund, an bring,” said Donnenfeld. many other nonprofits – have set up funds in endowment fund that will allow the “I want future boards to inherit a The Talmud advises that a person should hopes of emulating the incredible success of Journal to grow. financially sound organization that “divide his money into three: one third in university endowments, which can amass to “You have to find a way to try not only has working capital for day- land, one third in commerce, and one third billions of dollars. -

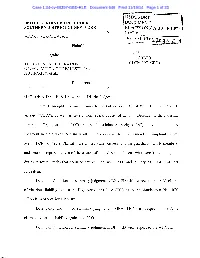

Order Denying Summary Judgment

Case 1:04-cv-00397-GBD-RLE Document 646 Filed 11/19/14 Page 1 of 23 """--"'~ --·- If 1jsri~· SDNY UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT '!D9CUMENT I ; , 1 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ·i E'·E·cr~oN~C"/11v- •.,JL.. , a.'\ . .. t · 1 '-' li... ..:I ------------------------------------ x :one#: FILEDjlI ' MARK I. SOKOLOW, et al., w~~·i: n::_~~I ~~.r!: N,Q_:t_U-10 l i ...... '"'"' , ..., ,._, ____ ,,.__~ ..... ~--,_,, ... __ ~, .. Plaintiffs, ' -against- ORDER THE PALESTINE LIBERATION 04 Civ. 397 (GBD) ORGANIZATION, THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY, et al., Defendants. ------------------------------------ x GEORGE B. DANIELS, United States District Judge: Plaintiffs brought this case pursuant to the Antiterrorism Act of 1992, 18 U.S.C. § 2331, et. seq. ("ATA"), as well as several non-federal causes of action. Defendants, the Palestine Liberation Organization ("PLO") and the Palestinian Authority ("PA"), move for summary judgment in their favor to dismiss all of the counts in the First Amended Complaint. (Def. Mem., ECF No. 497.) Plaintiffs are United States citizens and the guardians, family members, and personal representatives of the estates of United States citizens who were killed or injured during terrorist attacks that occurred between January 8, 2001 and January 29, 2004 in or near Jerusalem. Defendants' motion for summary judgment is DENIED with respect to the ATA claims of vicarious liability against the PA, except it is GRANTED as to the Mandelkorn Plaintiffs' ATA claim of vicarious liability. Defendants' motion for summary judgment is GRANTED with respect to the ATA claims of vicarious liability against the PLO. Defendants' motion for summary judgment is DENIED with respect to the ATA claims 1 Case 1:04-cv-00397-GBD-RLE Document 646 Filed 11/19/14 Page 2 of 23 of direct liability. -

Violations Against Palestinian Prisoners in Israeli Prisons and Detention Centers

Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association Addameer (Arabic for conscience) is a Palestinian non-governmental, civil institution that focuses on human rights issues. Established in late 1991 by a group of activists interested in human rights, the center offers support to Palestinian prisoners and detainees, advocates for the rights of political prisoners, and works to end torture through monitoring, legal procedures and solidarity campaigns. Addameer is surrounded by a group of grassroots supporters and volunteers, Addama’er, who share Addameer’s beliefs and goals, actively participate in its activities, and endeavor to support Addameer both financially and morally. Addameer is a member of the Palestinian NGO Network, the Palestinian Human Rights Organizations Council, the Palestinian Coalition for the Defense of Civil Rights and Liberties, and the Regional and International Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. Addameer is also a 2013 member of the International Network against Torture. Addameer believes in the importance of building a free and democratic Palestinian society based on justice, equality, rule of law and respect for human rights within the larger framework of the right to self-determination. Addameer strives to: • End torture and other forms of cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment and abolish the death penalty. • End arbitrary detention and guarantee fair, impartial, and public trials. • Support political prisoners by providing them with the legal aid and social and moral assistance and undertaking advocacy on their behalf. • Push for legislation that guarantees human rights and basic freedoms and ensure its implementation on the ground. • Raise awareness of human rights and rule of law issues in the local community. -

Security Council Provisional Fifty-Sixth Year

United Nations S/PV.4357 Security Council Provisional Fifty-sixth year 4357th meeting Monday, 20 August 2001, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Valdivieso ................................... (Colombia) Members: Bangladesh ...................................... Mr. Ahsan China .......................................... Mr. Wang Yingfan France .......................................... Mr. Doutriaux Ireland ......................................... Mr. Corr Jamaica ......................................... Mr. Ward Mali ........................................... Mr. Maiga Mauritius ....................................... Mr. Koonjul Norway ......................................... Mr. Strømmen Russian Federation ................................ Mr. Gatilov Singapore ....................................... Ms. Lee Tunisia ......................................... Mr. Jerandi Ukraine ......................................... Mr. Kulyk United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .... Mr. Eldon United States of America ........................... Mr. Cunningham Agenda The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian Question Letter dated 15 August 2001 from the Representatives of Mali and Qatar to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council (S/2001/797) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the interpretation of speeches delivered in the other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted -

Hamas, Israel, and the Recent Prisoner Exchange

A Mixed Blessing: Hamas, Israel, and the Recent Prisoner Exchange Yoram Schweitzer What is known as the Shalit deal between the Israeli government and Hamas, which saw the return of Gilad Shalit to Israel on October 18, 2011 and the mass release of Palestinian security prisoners, among them prisoners serving life sentences for the murder of Israelis,1 raised anew some fundamental issues that inevitably accompany deals of this sort between Israel and terrorist groups. Unlike in 1985 with the Jibril deal, when Israel released 1,150 Palestinian prisoners in exchange for three Israeli soldiers and whose high cost is reminiscent of the most recent swap, the price Israel paid in October 2011 was extensively and publicly debated. In addition to the cost itself, the reason for the heated discussion lay in the open, multi-channeled media coverage and the nature of contemporary public discourse. Hamas, whose negotiators were well aware of prisoner exchange precedents between Israel and terrorist organizations that had held soldiers and civilians in captivity, foremost among them the Jibril exchange model, presented the results of the deal as an historic victory for the Palestinian people.2 For their part, spokespersons for the Israeli government claimed that although the deal was a bitter pill for Israel to swallow, Hamas was in fact forced to make significant concessions it had previously refused to make and accept certain conditions insisted upon by Israel. The spokespersons claimed that with this in mind and under existing circumstances, this was the best deal possible.3 Yoram Schweitzer is a senior research associate and director of the Terrorism and Low Intensity Conflict Program at INSS. -

Unrwa Staff Incitement and Antisemitism

UNRWA STAFF INCITEMENT AND ANTISEMITISM FOLLOW-UP REPORT TO UNRWA DONOR STATES AHEAD OF MANDATE RENEWAL 25 September 2019 Presented at the United Nations Geneva, Switzerland Introduction Ahead of the upcoming United Nations General Assembly vote on the renewal of UNRWA’s mandate, UN Watch calls on all donors—including the EU, Germany, the UK, Sweden, Japan, Norway, Switzerland, Canada, the Netherlands, Spain and France—to reconsider their contributions to the agency. UNRWA not only faces severe allegations of corruption at the highest levels, as revealed by a recently-leaked UN ethics report,1 but also radicalizes Palestinian youth by indoctrinating them with an ideology that denies Israel’s existence, crude antisemitism, and the glorification of terrorism. Between September 2015 and April 2017, UN Watch published five separate reports exposing a total of 90 UNRWA staff and school Facebook pages containing antisemitism and terrorist incitement. Regrettably, although UNRWA received our reports and is well-aware of the issues, it continues to employ school teachers, principals and other staffers who support terrorism and antisemitism. This report exposes 10 new examples of such UNRWA staff Facebook pages in Lebanon, Gaza and Syria. Our research is well-known to UNRWA which has fundamentally failed to address the issue. Our 2015 reports were reported on by major media such as London’s Sunday Times. Regrettably, the response of then-UNRWA spokesman Chris Gunness was to lash out at UN Watch, and to deny or downplay the problem. Only after months of sustained media attention did the UN spokesman in New York announce quietly that a few employees had been suspended.2 The identities of the perpetrators, or the duration of their suspensions, were never disclosed.