Changes in the Landscape of West Cambridge, Part V: 1945 to 2000 Philomena Guillebaud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Cambridge Site Image

The Site 3.1 Site Description Shared Facilities Hub and Cavendish III Cambridge West Cambridge site image What is a Shared Facilities Hub? This will be a landmark building Welcome offering quality space for study, collaboration and socialising for Thank you for taking the time to attend our public academics, students and staff, as exhibition on proposals for the Shared Facilities well as for the local community. Architectural Design Hub and Cavendish III building on the West 4.3 General Arrangements Cambridge site. We would like to hear your views on our proposals: please take your time to review the material on display and fill in one of our Westfeedback Cambridge forms Site before Location you leave. Members of the project team Existing Paddock with Department of Veterinary Medicine in the distance North-East corner - Merton Hall Farmhouse are on hand and will be happy to answer any questions you have. The Project Team The design team has extensive experience in the delivery of Entrance Visual - Reception and exhibition level similar university facilities, bringing specific technical background What is Cavendish III? and knowledge that are crucial to achieving the best outcome for 64 this project. Cavendish III will relocate the current physics laboratory to a larger purpose- built building. The new premises will house research groups, laboratories, office and support accommodation. Crimson CMYK: C03 / M100 / Y66 / K12 RGB: R181 / G18 / B51 Pantone 200 C HTML: #B71234 0808 178 1295 [email protected] Aerial photograph of Department of Veterinary Medicine and site in 1955 Eastern Boundary - JJ Thomson Avenue Western Boundary - Existing Access Road and mature trees 29 Shared Facilities Hub and Cavendish III Cavendish III JJ Thomson Gardens Shared Facilities Hub Planning background Our application for the masterplan was submitted in June 2016 and is awaiting a decision from Masterplan Cambridge City Council. -

CASE Study 2 U Niversity of Cambridge: N Orth West Cambridge De Velopment a New Urban District on Former Green Belt Land

CASE STUDY 2 U NIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE: N ORTH WEST CAMBRIDGE DE VELOPMENT A new urban district on former green belt land Dr Clare Melhuish UCL Urban Laboratory September 2015 2 Case study 2 University of Cambridge: North West Cambridge Development Summary 1. North West Cambridge development: aerial view of site, with boundary marked in red 2. CGI model of whole site development, viewed from south 3. CGI model of phase 1 development, viewed from southeast. Images courtesy University of 1 Cambridge/AECOM 2 3 This case study demonstrates how universities can be proactive in engaging with local planning authorities to bring forward new development which delivers sustainable housing provision and social infrastructure within the context of an urban extension. The 150ha NorthWest development forms part of an expansion plan for Cambridge designed to accommodate its growing economy and population, particularly in the science and technology sector. The University is recognized as central to that economy, as a leading global research institution, but its very success has highlighted the need to address issues around affordable housing and transport. Construction commenced in 2014 and the first phase, comprising university and market housing and a community centre, is due for completion by Spring 2017. Later phases will deliver additional housing and potentially academic research and translation facilities. The project is supported by a masterplan developed by Aecom, and will feature a range of work by different architects working together in teams across a number of sites. Design quality has been central to the development agenda, and is underpinned by Code 5 for Sustainable Homes and the BREEAM Excellent standard, in a bid to create a national flagship for sustainable development. -

Churchill College Website – the Information on This Webpage Is Being Updated Most Regularly and Takes Precedence)

Postgraduate Student Handbook 2020-21 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................. 3 Key Dates 2020-21 .......................................................................................................................... 4 College Organisation and Governance ............................................................................................. 5 MCR.......................................................................................................................................... 5 The Governing Body .................................................................................................................. 5 The College Council ................................................................................................................... 5 Tutors ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Postgraduate Student Administrator ......................................................................................... 6 Mentors .................................................................................................................................... 6 Matriculation ............................................................................................................................ 6 Residence ........................................................................................................................................ -

Part 1 Background

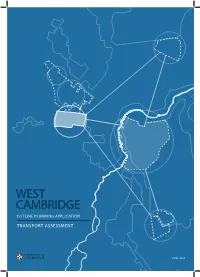

WEST CAMBRIDGE OUTLINE PLANNING APPLICATION TRANSPORT ASSESSMENT UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE JUNE 2016 Transport Assessment West Cambridge Development Document Control Sheet Project Name: West Cambridge Development Project Ref: 31500 / 5523 Report Title: Transport Assessment Doc Revision: 1.0 Date: June 2016 Name Position Signature Date Prepared by: J Hopkins Associate J Hopkins 13/06/2016 Reviewed by: G Callaghan Partner G Callaghan 13/06/2016 Approved by: G Callaghan Partner G Callaghan 13/06/2016 For and on behalf of Peter Brett Associates LLP Revision Date Description Prepared Reviewed Approved 1.0 13/06/16 Planning Application JPH GLC GLC Peter Brett Associates LLP disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of this report. This report has been prepared with reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the Client and generally in accordance with the appropriate ACE Agreement and taking account of the manpower, resources, investigations and testing devoted to it by agreement with the Client. This report is confidential to the Client and Peter Brett Associates LLP accepts no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report or any part thereof is made known. Any such party relies upon the report at their own risk. © Peter Brett Associates LLP 2016 J:\31500 West Cambridge\Word\Reports\Transport Assessment\160613 - Transport Assesment - Planning Application Version.docx ii Transport Assessment West Cambridge Development Contents Executive -

West Cambridge: the Two World Wars and the Inter-War Lull Philomena Guillebaud

West Cambridge: the two World Wars and the inter-war lull Philomena Guillebaud This is the fourth of a series of articles tracing the history precise fgures exist, the colleges owned more than of the landscape of west Cambridge following the enclosure half the area of the Parish, some acquired through of the former West Fields.1 In the two World Wars, west benefactions and some bought, and many of the aca- Cambridge sufered no physical damage but saw the ap- demics took their exercise walking or riding through pearance of large temporary structures: a military hospi- the felds. tal in WW1 and an aircraft repair factory in WW2, each The signifcance of the parish in this narrative lies subsequently – and after much delay – demolished after in the fact that parishes were the units of enclosure peace returned. In the interwar period, a combination of under the Parliamentary Enclosure Acts of the 18th fnancial constraints and an efective campaign waged by and 19th centuries. As the major owners, the col- the Cambridge Preservation Society, nominally a town-and- leges had a considerable impact on the outcome of gown organisation but weighted on the side of University the enclosure of St Giles, which took place between interests, saw very litle development on the west side of 1802 and 1805, not (so far as can be determined) by town. Clare College’s Memorial Court was built, as was the altering the statistics of ownership but very much by new University Library: the frst University building since infuencing the location of the lands alloted to the the Observatory to be built outside the town centre. -

16/1134/OUT Agenda Item Number

PLANNING COMMITTEE DATE: 29 July 2021 Application 16/1134/OUT Agenda Item Number Date Received 16 June 2016 Officer Fiona Bradley Target Date EoT 29 October 2021 Ward Newnham Site Land West of JJ Thomson Avenue, Cambridge, CB3 0FA Proposal Outline planning permission with all matters reserved is sought for: - Up to 370,000 sq m of academic floor space (Class D1 space), commercial/research institute floor space (Class B1b and sui generis research uses) of which not more than 170,000 sq m will be commercial floor space (Class B1b). - Up to 2,500sqm of nursery floorspace (Class D1). - Up to 4,000sqm of retail/food and drink floorspace (Classes A1-A5). - Up to 4,100sqm and not less than 3,000sqm for assembly and leisure floor space; - Up to 5,700sqm of sui generis uses, including an energy centre and data centre; - Associated infrastructure, including roads (including adaptions to highway junctions on Madingley Road), pedestrian, cycle and vehicle routes, parking, drainage, open spaces, landscaping and earthworks; and demolition of existing buildings and breaking up of hard standing Applicant Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University of Cambridge SUMMARY The development accords with the Development Plan for the following reasons: 1) The principle of development accords with Cambridge Local Plan 2018 Policy 19, in providing a mix of academic and commercial uses within an allocated employment site. 2) The development will make an important contribution to jobs provision in Cambridge 1 and the wider area, with a maximum potential Gross Value Added (GVA) of £864.8 million for the local and regional economy. -

GRANGE FARM, WEST CAMBRIDGE ACCESS and TRANSPORT APPRAISAL on Behalf of St John’S College

GRANGE FARM, WEST CAMBRIDGE ACCESS AND TRANSPORT APPRAISAL On behalf of St John’s College PUBLIC JUNE 2017 GRANGE FARM, WEST CAMBRIDGE ACCESS AND TRANSPORT APPRAISAL On behalf of St John's College Type of document (version) Project no: 70024510 Date: June 2017 WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff 62-64 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 1LA Tel: +0 (0) 1223 558 050 Fax: +0 (0) 1223 558 051 www.wsp-pb.com QUALITY MANAGEMENT ISSUE/REVISION FIRST ISSUE REVISION 1 REVISION 2 REVISION 3 Remarks Draft Final Date 25.01.17 02.06.17 Prepared by L Kirby L Kirby Approved by LK Signature 02.06.17 Checked by N Eggar N Eggar Approved by NE Signature 02.06.17 Authorised by N Eggar N Eggar Approved by NE Signature 02.06.17 Project number 70024510 70024510 Report number 1 2 \\uk.wspgroup.com\Cent \\uk.wspgroup.com\Cen ral tral Data\Projects\700245xx\ Data\Projects\700245x 70024510 - Grange x\70024510 - Grange File reference Road and Madingley Road and Madingley Road\C Road\C Documents\Reports\Rep Documents\Reports\Re orts ports ii PRODUCTION TEAM CLIENT St John’s College Ms S Wood WSP Project Manager Mr L Kirby Project Director Mr N Eggar Grange Farm, West Cambridge WSP On behalf of St John's College Project No 70024510 June 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................1 2 TRANSPORT POLICY REVIEW ..................................................2 3 EXISTING TRANSPORT CONDITIONS .......................................9 4 TRIP GENERATION AND DISTRIBUTION ................................18 5 PROPOSED TRANSPORT -

Minutes of the Meeting

University of Cambridge West Cambridge Community Group Minutes of the Meeting 2 March 2016 in the Hauser Forum Seminar Room on the West Cambridge site. Attendees: Harvey Bibby, Lansdowne Road resident (Chair) Hugh Purser, Clerk Maxwell Road Residents Association Eddie Powell, Clerk Maxwell Road Residents Association Henry Day, Conduit Head Road Dai Davies, North Newnham Residents Association Ian Sutcliffe, Madingley Road Residents Association Edward Byam Cook, Madingley Parish Council Rod Cantrill, Newnham Ward Councillor Mike Donelan, University Accommodation Service - West Cambridge Apartments Nick Brooking, University Sport Centre Alex Reid, East Paddock Campaign Will Hudson, West Cambridge Safety Committee John Evans, Cambridge City Council Heather Topel, University Biky Wan, University Jonathan Rose, AECOM (Consultant) Nick Askew, AECOM (Consultant) Elizabeth Crump, AECOM (Consultant) Apologies Sian Reid, Newnham Ward Lucy Nethsingha, Newnham Ward Morcom Lunt, Federation of Residents’ Association Jon Elphick, Clerk Maxwell Road Residents’ Association Nicky Blanning, University Accommodation Service - West Cambridge Apartments Sue Davis, University Childcare Services WELCOME Harvey Bibby welcomed the group. 1. INTRODUCTIONS AND APOLOGIES AND INTRODUCTION OF THE DEPUTY CHAIR Introductions were made and apologies were presented as above. Will Hudson introduced himself as the Deputy Chair and has other roles within the University and understanding of committees to offer the role. 2. MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING No comments were made to the minutes of the last meeting. 3. WEST CAMBRIDGE DEVELOPMENT UPDATE Heather Topel thanked members for their commitment to the group and patience with reference to the fact that the group had not met since May 2015. During the period, the team had been working through issues raised through consultation and addressing the problems, including aspects related to the transport modelling which would be under detailed discussion next week. -

Transport Assessment Proforma

WEST CAMBRIDGE OUTLINE PLANNING APPLICATION TRANSPORT ASSESSMENT PROFORMA UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE OCTOBER 2020 STANTEC UK LTD UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 45339 - WEST CAMBRIDGE DEVELOPMENT Planning Application Transport Assessment Cover Sheet PROPOSAL Proposal: describe the proposal West Cambridge is an academic and commercial research development in the western side of Cambridge promoted by the University of Cambridge, allocated in the Cambridge Local Plan 2018. The location of this Site is shown on the plan below: The existing masterplan for West Cambridge that was granted an approval in 1999 forms the basis of the current development on the Site. Together with the pre-existing development on the Site, the 1999 masterplan envisaged just under 275,000m2 of development, approximately 47% of which would be academic, 15% research institute and 22% commercial research. Policy 19 of the Cambridge Local Plan 2018 promotes the densification of the West Cambridge through a revised masterplan subject to a number of conditions. The University of Cambridge is producing a new masterplan for the Site which increases the amount of development to approximately 500,280m2. In detail: J:\45339 - West Cambridge 2018\Word\CCC TA Proforma\Revised CCC TA Proforma - issued to the UofC - 201014.docx 1 Proposal: describe the proposal Total Existing and Proposed Full Development - Land Use Mix Land-Use (GFA) Existing 1999 Consent Existing Devt Proposed TOTAL Implemented Not to be Additional Devt FULL DEVT Development Implemented Demolished to Full Devt (m2) (m2) (m2) -

Churchill Review 2019

CHURCHILL CHURCHILL REVIEW REVIEW Volume 56 | 2019 Volume 56 Volume Churchill College Cambridge | CB3 0DS 2019 www.chu.cam.ac.uk CHURCHILL REVIEW Volume 56 | 2019 ‘ It’s certainly an unusual honour and a distinction that a college bearing my name should be added to the ancient and renowned foundations which together form the University of Cambridge.’ Sir Winston Churchill, 17 October, 1959 Sir Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admirality c. 1911–13 Credit: CSCT 05 002 017 CONTENTS EDITORIAL..................................................................................................................................................................................................7 FROM THE MASTER ......................................................................................................................................................................9 THE COLLEGE YEAR ...............................................................................................................................................................15 The Churchill Way Senior Tutor’s Report ............................................................................................................... 17 A Diverse Community in the Pursuit of Excellence Tutor for Advanced Students’ Report .................................................................................. 21 Making the Most of our Resources Bursar’s Report ........................................................................................................................ 25 'HOLYHULQJD)OH[LEOH(IÀFLHQWDQG)ULHQGO\(QYLURQPHQW -

PLANNING COMMITTEE DATE: 7 FEBRUARY 2018 Application Number 17/1799/FUL Agenda Item Date Received 17Th October 2017 Officer

PLANNING COMMITTEE DATE: 7TH FEBRUARY 2018 Application 17/1799/FUL Agenda Number Item Date Received 17th October 2017 Officer John Evans Target Date 6th February 2017 Ward Newnham Site Land West Of JJ Thomson Avenue, Cambridge, CB3 0FA Proposal Development of 37,160 sqm for D1 academic floor space to accommodate the relocation of the Cavendish Laboratory, namely; all associated infrastructure including drainage, utilities, landscape and cycle parking; strategic open space to the south and west of the new Cavendish; modifications to JJ Thomson Avenue to provide disabled parking and changes to road surface materials; alterations to the existing access to Madingley Road to the north west to enable servicing; and demolition of Merton Hall Farmhouse and removal of existing Vet School access road from JJ Thomson Avenue. Applicant Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University of Cambridge SUMMARY The development accords with the Development Plan for the following reasons: 1. The proposal is in accordance with Policy 18 of the emerging Local Plan which supports densification of the site. 2. The proposed new building is of high quality design and will successfully integrate in the context of surrounding buildings and the emerging outline masterplan strategy. 3. There will be no significant adverse visual impact from or to neighbouring residential properties. 4. Noise and amenity impacts arising from the development can be addressed by imposition of appropriate conditions. 5. The proposal is acceptable in transport terms. A high quality 3.5m segregated cycle link will be provided on JJ Thomson Avenue. A package of mitigation is provided for cycle improvements off site. -

Freshers' Guide 2020

Churchill College MCR Freshers Guide Churchill College MCR Freshers’ Guide 2020 1 Churchill College MCR Freshers Guide 2 Churchill College MCR Freshers Guide Hello Freshers! Welcome to Cambridge! Congratulations on starting your courses at the University of Cambridge and on becoming part of Churchill college, the best college in Cambridge. As a postgraduate student at Churchill College, you are a member of the MCR (Middle Common Room) community. The community is run, in part, by the MCR committee: a group of student volunteers who represent you at College and organise social and academic events throughout the year. We aim to make your time at Cambridge as fun and engaging as possible and encourage you to become a part of the committee should you so wish. Understandably, this year will be unlike any other year in Cambridge. However, the college and your MCR committee are still committed to supporting you. Until things are back to normal, we will be running many socially distant, household-oriented events to help you feel settled and supported during your time here. These range from scavenger hunts to socially distant trips to the pub to movie nights to BBQs. While things will not be completely normal when you arrive, there will still be lots to do. And if there is anything that you need, please get in touch with your committee, we are here to help. To make sure you don’t miss anything, check the event calendar on the Churchill MCR website and keep an eye out for the weekly Gazette on your Cambridge emails.