Pittsburgh IT Cluster Is in Universities and Training Institutes, Instruments, Research Organizations, Software Development and Information Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Together to Build Bridges to the Future

DEC. 612, 2019 5 Working together to build bridges to the future SENATOR JOHN HEINZ HISTORY CENTER GETTY IMAGES SPONSORED BY: 2 PITTSBURGH BUSINESS TIMES THE PITTSBURGH REGION AND OUR NEXT 75 Th e next chapter in our region’s history eventy-fi ve years. Th at’s an entire improving quality of place. lifetime. We will only succeed in reaching S When you get to 75 years – so this goal if we join together and involve we’re told – you’re wiser. Your world- as many people as possible. At the Our view broadens. You understand how Next 75 Summit in June and the Allegh- things succeed and how things fail. eny Conference’s 75th Annual Meeting Over the past 75 years of regional earlier this week, packed rooms, buzz- transformation, two generations of lead- ing with the energy and enthusiasm of Jeff Broadhurst and Toni Murphy are ers have shaped the story of our region, everyone present, proved a point: we co-chairs of the Allegheny Conference and a third is taking the reins. have the ability to propel this place for- on Community Development’s Our Next Much of 2019 was devoted to listening ward to achieve its fullest potential. 75 initiative. to emerging leaders – that third genera- Such a future off ers: tion – as well as to the voices of experi- • A Strong Economy that leverages ence. From Butler to Washington … from our human and natural resources with a will give them pause – and give them Greensburg to Pittsburgh … we invit- focus on tech and innovation, a well-cal- cause – to draw inspiration from us, ed leaders from across our region to the ibrated business ecosystem and eff ective much as we do from the leaders who table to gather directly from them more marketing. -

Higher Ed in Transition

THE MAGAZINE OF THE MASTER BUILDERS’ ASSOCIATION OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA JULY/AUGUST 2016 Higher Ed in Transition Mid-Year Results The Trend in Student Housing CMU’s New Scott Hall What to Expect from the Cracker STONE VENEER CLAY BRICK HARDSCAPE MASONRY Carnegie Mellon University Sherman and Joyce Bowie Scott Hall Congratulations to CMU on their new Sherman and Joyce Bowie Scott Hall. A 100,000 SF building, home for Nano Fabrication, Wilton E. Scott Institute for Energy Innovation and a new campus location for the Biomedical Engineering Department. Jendoco is a proud partner of CMU Carnegie Mellon University Industry Intelligence. Focused Legal Perspective. HIGH-YIELDING RESULTS. Meet our construction attorneys at babstcalland.com. Whether it’s negotiating a construction contract, litigating a mechanics’ lien or bond claim, resolving bid protests or dealing with delay, inefficiency, or acceleration claims, we help solve legal problems in ways that impact your business and add value to your bottom line. PITTSBURGH, PA I CHARLESTON, WV I STATE COLLEGE, PA I WASHINGTON, DC I CANTON, OH I SEWELL, NJ Babst_Construction_DEVPGH_8.625x11.125.indd 1 3/6/16 9:41 PM Contents2016 PUBLISHER Tall Timber Group www.talltimbergroup.com EDITOR Jeff Burd 412-366-1857 Cover image: [email protected] Carnegie Mellon’s Scott Hall. PRODUCTION Carson Publishing, Inc. Kevin J. Gordon ART DIRECTOR/GRAPHIC DESIGN Carson Publishing, Inc. Jaimee D. Greenawalt CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Anna Burd CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHY Tall Timber Group Master Builders’ Association -

Making the Right Move

MAKING THE RIGHT MOVE Investing and Creating Jobs in the Pittsburgh Region REAL PITTSBURGH REAL PEOPLE Looking Ahead: 2014 and Beyond Imagining a Bright Future for Our Region – and Making it Happen By Charles E. Bunch In many ways, the Pittsburgh region has com- Boomers. We’re seeing this on our job search engine within Imag- pleted the economic, environmental and qual- inePittsburgh.com, where the number of open jobs across the 10- ity-of-life transformation begun 30 years ago. county Pittsburgh region numbered around 25,000 at last count. We bottomed out in 1983, with an unemploy- ment rate over 18 percent. Throughout 2013, The Conference is addressing this opportunity in a variety of ways, in- WHEN YOU INVEST IN THE cluding through our robust talent attraction and retention initiative, COMMUNITY, THE RETURNS our jobless rate outperformed the state and the nation as a whole. We’re closing the year with the largest workforce which includes ImaginePittsburgh.com. We’re also working with ARE GUARANTEED. in regional history – about 100,000 more people employed than at our partners in workforce development to increase the supply of trained At Huntington, we know how important it is to give back to workers in the region. One such program, ShaleNET, has been such the community. After all, we do more than just work here – we industrial peak in 1979. live and raise our families here too. And after everything this a success that the federal government has increased its investment to community has done for us, we’re just happy to be able to We are enjoying the fruits of three decades of hard work by countless expand it to other states. -

Flesh Is Heir

cover story 125 Years of r e m o v i n g a n d Preventing t h e i l l s t o w h i c h fleSh is heiR b y b arbara I. Paull, e r I c a l l o y d , e d w I n K I ester Jr., J o e m ik s c h , e l a I n e v I t o n e , c h u c K s ta r e s I n I c , a n d sharon tregas ki s lthough the propriety of establishing a medical school here has been sharply questioned by some, “ we will not attempt to argue the question. Results will determine whether or not the promoters of the enterprise were mistaken in their judgment Aand action. The city, we think, offers ample opportunity for all that is desirable in a first-class medical school, and if you will permit me to say it, the trustees and faculty propose to make this a first-class school.” —John Milton Duff, MD Professor of Obstetrics, September 1886 More than three decades after the city’s first public hospital was established, after exhausting efforts toward a joint charter, Pittsburgh physicians founded an indepen- dent medical college, opening its doors in September 1886. This congested industrial city—whose public hospital then performed more amputations and saw more fatal typhoid-fever cases per capita than any other in the country—finally would have its own pipeline of new physicians for its rising tide of diseased and injured brakemen, domestics, laborers, machinists, miners, and steelworkers from around the world, as well as the families of its merchants, professionals, and industry giants. -

Universities and Innovation Ecosystems: a Dynamic Capabilities Perspective Sohvi Heaton,1,* Donald S

Industrial and Corporate Change, 2019, 1–19 doi: 10.1093/icc/dtz038 Original article Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icc/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/icc/dtz038/5526923 by Loyola Marymount University user on 08 July 2019 Universities and innovation ecosystems: a dynamic capabilities perspective Sohvi Heaton,1,* Donald S. Siegel,2 and David J. Teece3 1College of Business, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA 90045-2659, USA. e-mail: [email protected], 2School of Public Affairs, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85004-0687, USA. e-mail: [email protected] and 3Institute for Business Innovation, Haas School of Business, U.C. Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720-1234, USA. e-mail: [email protected] *Main author for correspondence. Abstract Universities play an important role in innovation ecosystems. In addition to developing human capital and advancing technology, they are increasingly expected to participate as economic development partners with industry and local, state, and national governments. Models such as the “Triple Helix” have been advanced to frame the assessment of interactions among academia, industry, and govern- ments that may foster economic development. Such models highlight the boundary-spanning roles of universities and provide a predetermined list of actions universities could take to strengthen their eco- system. Unfortunately, the flexible and entrepreneurial management of universities required to make this model work has virtually been ignored in the academic literature. We propose the dynamic capa- bilities framework to guide how universities might manage their innovation ecosystems. We use this framework to analyze the role of the university throughout the ecosystem lifecycle. -

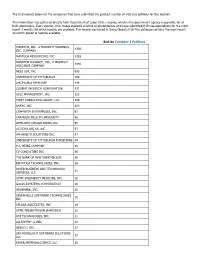

The H1B Records Below List the Companies That Have Submitted the Greatest Number of H1B Visa Petitions for This Location

The H1B records below list the companies that have submitted the greatest number of H1B visa petitions for this location. This information was gathered directly from Department of Labor (DOL) records, which is the government agency responsible for all H1B submissions. Every quarter, DOL makes available a listing of all companies who have submitted H1B visa applications for the most recent 3 months for which records are available. The records contained in Going Global's H1B Plus database contains the most recent 12-month period of records available. Sort by Company | Petitions MASTECH, INC., A MASTECH HOLDINGS, 4339 INC. COMPANY MASTECH RESOURCING, INC. 1393 MASTECH ALLIANCE, INC., A MASTECH 1040 HOLDINGS COMPANY NESS USA, INC. 693 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH 169 UHCP D/B/A UPMC MEP 144 COGENT INFOTECH CORPORATION 131 SDLC MANAGEMENT, INC. 123 FIRST CONSULTING GROUP, LLC 104 ANSYS, INC. 100 COMPUTER ENTERPRISES, INC. 97 CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY 96 INTELLECT DESIGN ARENA INC. 95 ACCION LABS US, INC. 63 HM HEALTH SOLUTIONS INC. 57 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PHYSICIANS 44 H.J. HEINZ COMPANY 40 CV CONSULTING INC 36 THE BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON 36 INFOYUGA TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 36 BAYER BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOGY 31 SERVICES, LLC UPMC EMERGENCY MEDICINE, INC. 28 GALAX-ESYSTEMS CORPORATION 26 HIGHMARK, INC. 25 SEVEN HILLS SOFTWARE TECHNOLOGIES 25 INC VELAGA ASSOCIATES, INC 24 UPMC PRESBYTERIAN SHADYSIDE 22 DVI TECHNOLOGES, INC. 21 ALLEGHENY CLINIC 20 GENCO I. INC. 17 SRI MOONLIGHT SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 17 LLC BAYER MATERIALSCIENCE, LLC 16 BAYER HEALTHCARE PHARMACEUTICALS, 16 INC. VISVERO, INC. 16 CYBYTE, INC. 15 BOMBARDIER TRANSPORTATION 15 (HOLDINGS) USA, INC. -

United States District Court Southern District of New York

Case 1:09-cv-01714-GHW-RWL Document 314 Filed 05/07/20 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK x In re DEUTSCHE BANK AG SECURITIES : Master File No. 1:09-cv-01714-GHW-RWL LITIGATION : : CLASS ACTION : This Document Relates To: : DECLARATION OF ALFRED G. YATES, : JR. FILED ON BEHALF OF LAW OFFICE ALL ACTIONS. : OF ALFRED G. YATES JR., P.C. IN x SUPPORT OF APPLICATION FOR AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND EXPENSES Case 1:09-cv-01714-GHW-RWL Document 314 Filed 05/07/20 Page 2 of 4 I, Alfred G. Yates, Jr., declare as follows: 1. I am principal of the firm of Law Office of Alfred G. Yates Jr., P.C. I am submitting this declaration in support of my firm’s application for an award of attorneys’ fees and expenses/charges (“expenses”) in connection with services rendered in the above-entitled action. 2. This firm is counsel of record for plaintiff Edward P. Zemprelli. 3. My firm participated in the research and drafting of the original Class Action Complaint filed on behalf of Edward P. Zemprelli in February of 2009 and the subsequent Consolidated and Amended complaints in this action; my firm continued to consult with Lead Counsel and plaintiff Zemprelli throughout the litigation including review and approval by plaintiff Zemprelli of the complaints and provided periodic status updates to plaintiff Zemprelli until his death in 2017. The information in this declaration regarding the firm’s time and expenses is taken from time and expense printouts and supporting documentation prepared and/or maintained by the firm in the ordinary course of business. -

Pittsburgh IT Cluster Is in Universities and Training Institutes, Instruments, Research Organizations, Software Development and Information Security

Professor Michael E. Porter, Harvard University Council on Competitiveness Monitor Group ontheFRONTIER Pittsburgh CLUSTERS OF INNOVATION INITIATIVE ATLANTA PITTSBURGH RESEARCH TRIANGLE SAN DIEGO WICHITA This report may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form beyond copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. copyright law and excerpts by reviewers for the public press, without written permission from the publishers. ISBN 1-889866-52-0 To download this report or learn more about the Clusters of Innovation Initiative, please visit www.compete.org or write to: Council on Competitiveness 1500 K Street, NW Suite 850 Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 682-4292 Fax: (202) 682-5150 Email: [email protected] Copyright ©April 2002 Council on Competitiveness Professor Michael E. Porter, Harvard University Monitor Group ontheFRONTIER Printed in the United States of America cover photo by John Wee Pittsburgh CLUSTERS OF INNOVATION INITIATIVE Professor Michael E. Porter, Harvard University Monitor Group ontheFRONTIER Council on Competitiveness CLUSTERS OF INNOVATION INITIATIVE: REGIONAL FOUNDATIONS OF U.S. COMPETITIVENESS CONTENTS Foreword by the Co-Chairs of the Clusters of Innovation Initiative . iv Acknowledgments . v National Steering Committee Members and Regional Advisors . vii Report Overview . .viii Highlights . .ix Executive Summary . xii Introduction . 1 1 Economic Competitiveness and Regional Innovative Capacity . 3 2 Regional Study Methodology . 14 3 Assessment of the Pittsburgh Regional Economy . 20 4 Competitiveness of Selected Clusters . 47 The Biotechnology / Pharmaceutical Cluster . 47 The Information Technology Cluster . 68 The Production Technology Cluster . .85 Sustaining Competitive Advantage: 5 Lessons, Challenges, and Opportunities . 103 Endnotes . 117 Appendices . 121 1. Definition of Measurements . -

Forerunner™ ATM Switch User's Manual

ForeRunner™ ATM Switch User’s Manual fs MANU0149-01 - March, 1997 Software Version 4.1.x FORE Systems, Inc. 1000 FORE Drive Warrendale, PA 15086 Phone: 412-742-4444 FAX: 412-772-6500 http://www.fore.com Legal Notices Copyright © 1995-1997 FORE Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. FORE Systems is a registered trademark, and ForeRunner, ForeView, ForeThought, ForeRunnerLE, PowerHub, and CellPath are trademarks of FORE Systems, Inc. All other brands or product names are trademarks of their respective holders. U.S. Government Restricted Rights. If you are licensing the Software on behalf of the U.S. Government (“Government”), the following provisions apply to you. If the Software is supplied to the Department of Defense (“DoD”), it is classified as “Commercial Computer Software” under paragraph 252.227-7014 of the DoD Supplement to the Federal Acquisition Regu- lations (“DFARS”) (or any successor regulations) and the Government is acquiring only the license rights granted herein (the license rights customarily provided to non-Government users). If the Software is supplied to any unit or agency of the Government other than DoD, it is classified as “Restricted Computer Software” and the Government’s rights in the Soft- ware are defined in paragraph 52.227-19 of the Federal Acquisition Regulations (“FAR”) (or any successor regulations) or, in the cases of NASA, in paragraph 18.52.227-86 of the NASA Supplement to the FAR (or any successor regulations). Printed in the USA. No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced in any form. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation with- out prior written permission is prohibited, except as allowed under the copyright laws. -

The Physical and Cultural Development of Pittsburgh's Highland Park Neighborhood, 1778-1900

1 Building a Community: The Physical and Cultural Development of Pittsburgh’s Highland Park Neighborhood, 1778-1900 Nathaniel Mark, The Johns Hopkins University1 INTRODUCTION American history has a unique relationship with suburban residential life. Unlike many of their continental European counterparts, American commuter suburbs since their inception in the 19th century have been a symbol of the growing wealth of the American population. Indeed, suburban life and the American dream are often analogous concepts. Since Pittsburgh emerged as an industrial city, its suburbs have steadily grown from small upper-class rural retreats into the most prominent form of residential communities in Western Pennsylvania.2 Yet, the dominance of suburbs was not the inevitable outcome of industrialization. Prior to the latter half of the 19th century it was not even apparent that Pittsburgh’s well-to- do would rather live in peripheral areas than in the inner city. 1 This research was conducted as an undergraduate sophomore thesis in history. It was completed in 2012. Contact the author at [email protected] or through his website at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nathaniel_Mark/. 2 Frank Hobbs and Nicole Stoops, U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Special Reports, Series CENSR-4, Demographic Trends in the 20th Century (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002), 33. 2 Many historians and sociologists have analyzed the intricate process of early suburban development, and how these suburbs acquired the reputation of wealth and power that have remained a part of the suburban legacy. Sam Bass Warner, in his pioneering 1962 book Streetcar Suburbs, describes how Boston was transformed from a walking city to a modern metropolis. -

March/April 2010 (PDF)

the magazine of the master builders’ association of western pennsylvania march/april 2010 Oakland A Neighborhood In Demand EPA stormwAtEr rEgulAtions Add cost mAnAging thE rEcEssion biggEst risks mbA building ExcEllEncE winnErs ArrA first yEAr rEPort cArd BG Mar_Apr_10.indd 1 3/8/10 12:43 PM To start your development project make One-STOp at L.r. kimbaLL BEDROCK REPUTATION. STEADFAST PRINCIPLES. TARgETED RESULTS. ExPERTLy MANAgED. Developers call on our 56 years of experience and L.R. Kimball has provided one-stop services for many in-house capabilities to provide one-stop support from: of Pennsylvania’s most successful developments such as: • Civil and Environmental Specialists offering laboratory testing, civil site services, geotechnical • Innovation Park in State College drilling, soils and concrete testing, aerial mapping • Southpointe II in Washington County and surveying • Cherrington Office Park in Allegheny County • Traffic Experts who perform traffic studies and • Heinz Field Site Plan for the Pittsburgh Sports and obtain highway occupancy permits Exhibition Authority • Architecture Teams who design state-of-the-art • More than a dozen Wal-Mart, Lowe’s, LEED® certified facilities and Sam’s Club complexes With the heritage of a family-owned business that WE STAKE OUR REPUTATION ON IT. operates on a national scale, L.R. Kimball has L.R. Kimball will always do our best to ensure that assisted with hundreds of warehouse, office, retail your goals are met and that you receive the highest and mixed-use construction projects drawing from possible value. a range of over 60 integrated services to become a solid choice of developers in Pennsylvania. -

Pittsburgh, PA Previous GTCA City 2013

Pittsburgh, PA Previous GTCA City 2013 Contact: Tom Piccone ([email protected]); Andy Wang ([email protected]) The Church of God in Pittsburgh The Church of God in Pittsburgh was originally established as the Church in Pittsburgh in 1983, primarily through a migration of saints mainly from Ohio. Some years after a turmoil, the Church of God in Pittsburgh was incorporated in 2017. The church does not presently have a meeting hall, but meets on university campuses and in various saints’ homes. Approximately 40 currently gather on Lord’s Day mornings, including four children. The racial composition of the church is 59% Chinese and 16% Caucasian, with the remaining 25% a mix of Korean, Vietnamese, Black, and Indian. The current church life in Pittsburgh focuses primarily on campus work at the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) and Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), though the need to gain more families is of equal priority (and not necessarily separate). Each year, the Lord adds remaining fruit to His Body through the saints’ labor on the campuses to gain college and graduate students, and sometimes university staff. In the past 12 years of campus work, dozens have been gained, but most have moved away. Only a handful of them have not been Asian. While the saints in Pittsburgh welcome all who would like to move here, we particularly see a need for young American families to migrate to the Pittsburgh area in order to share the burden of shepherding and gaining some from the population of American students and families for the strengthening of His testimony in this locality and region.