Visual and Performing Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light on the Darkness

Fall 2016 the FlameTHE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY LIGHT ON THE DARKNESS Psychology alumna Jean Maria Arrigo dedicated 10 years of her life to exposing the American Psychological Association’s secret ties to US military interrogation efforts MAKE A GIFT TO THE ANNUAL FUND TODAY the Flame Claremont Graduate University THE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY fellowships play an important role Fall 2016 The Flame is published by in ensuring our students reach their Claremont Graduate University’s Office of Marketing and Communications educational goals, and annual giving 165 East 10th Street Claremont, CA 91711 from our alumni and friends is a ©2016 Claremont Graduate University major contributor. Here are some of VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT our students who have benefitted Ernie Iseminger ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS from the CGU Annual Fund. Max Benavidez EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Andrea Gutierrez “ I am truly grateful for the support that EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ADVANCEMENT COMMUNICATIONS CGU has given me. This fellowship has Nicholas Owchar provided me with the ability to focus MANAGING EDITOR on developing my career.” Roberto C. Hernandez Irene Wang, MBA and MA DESIGNER Shari Fournier-O’Leary in Management DIRECTOR, DESIGN SERVICES Gina Pirtle I received fellowship offers from other ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, INTEGRATED MARKETING “ Alfie Christiansen schools. But the amount of my fellowship ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS from CGU was the biggest one, and Sheila Lefor I think that is one of my proudest DISTRIBUTION MANAGER moments.” Mandy Bennett Akihiro Toyoda, MBA PHOTOGRAPHERS Carlos Puma John Valenzuela If I didn’t have the fellowship, there is William Vasta “ Tom Zasadzinski no way I would have been able to study for a PhD. -

THE LIST Highest Assessed Properties in L.A

DECEMBER 10, 2018 LOS ANGELES BUSINESS JOURNAL 9 NEXT WEEK RADIO STATIONS The Largest City Contractors and Ranked by October 2018 Nielsen Audio ratings THE LIST Highest Assessed Properties in L.A. Rank Station Audience Share Format Profile Sales Managers Top Local Executive • name • October 2018 • format • station owner • name • address • October 2017 • target age group • year founded • title • language • phone KRTH-FM (101.1) 5.0 oldies Entercom Communications Corp. David Severino Jeff Federman 1 5670 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 200 4.5 35-54 1972 Market Manager, General Los Angeles 90036 English Manager (323) 936-5784 KOST-FM (103.5) 4.9 adult contemporary iHeartMedia Inc. John Bassarelli Kevin LeGrett 2 3400 W. Olive Ave., Suite 550 4.5 25-54 1982 President, Market Manager Burbank 91505 English (818) 559-2252 KBIG-FM (104.3) 4.8 hot adult contemporary iHeartMedia Inc. Julie Martzke Kevin LeGrett 3 3400 W. Olive Ave., Suite 550 6.4 25-54 1965 George Flora President, Market Manager Burbank 91505 English (818) 559-2252 KIIS-FM (102.7) 4.2 top 40 hits iHeartMedia Inc. Ari Tsekouras Kevin LeGrett 4 3400 W. Olive Ave., Suite 550 4.5 18-49 1947 Jodi Dewey President, Market Manager Burbank 91505 English (818) 559-2252 KTWV-FM (94.7) 4.2 smooth rhythym and blues Entercom Communications Corp. John Bassanelli Jeff Federman 5670 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 200 4.3 35-54 1987 Market Manager, General Los Angeles 90036 English Manager (323) 937-9283 KCBS-FM (93.1) 3.8 adult hits Entercom Communications Corp. John Bassanelli Jeff Federman 6 5670 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 200 3.6 25-54 2005 Market Manager, General Los Angeles 90036 English Manager (323) 937-9331 KLVE-FM (107.5) 3.8 adult contemporary Univision Communications Jason Strongin Luis Patino 5999 Center Drive, Fourth Floor 3.6 18-49 1972 General Manager Los Angeles 90045 Spanish (310) 846-2868 KFI-AM (640) 3.7 news, talk iHeartMedia Inc. -

Broadcast Actions 9/24/2007

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46577 Broadcast Actions 9/24/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/18/2007 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR TRANSFER OF CONTROL GRANTED CA BTCED-20070731BYI KAZU 43591 FOUNDATION OF CALIFORNIA Voluntary Transfer of Control, as amended STATE UNIVERSITY, MONTEREY From: FOUNDATION OF CALIF. STATE UNIV., MONTEREY BAY (OLD E 90.3 MHZ BAY BOARD) To: FOUNDATION OF CALIF. STATE UNIV., MONTEREY BAY (NEW CA , PACIFIC GROVE BOARD) Form 316 Actions of: 09/19/2007 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION PERMIT DISMISSED CO BPED-19970728MA 970728MA J P I RADIO INCORPORATED CP FOR NEW FM STATION 87628 E CO , STRASBURG Supplement filed 7/17/2001 97.7 MHZ Engineering Amendment filed 01/21/2005 Engineering Amendment filed 01/25/2005 Dismissed 9/19/2007. See DA 07-3969, released 9/19/2007. Page 1 of 27 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46577 Broadcast Actions 9/24/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/19/2007 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION PERMIT DISMISSED CO BPED-19980417MI 980417MI CSN INTERNATIONAL CP FOR NEW NCE FM STATION 90910 E CO , STRASBURG 97.7 MHZ SUPPLEMENT FILED 7/19/2001. -

USC Radio Group

The Driving Force and Center of the Bay Area and Southern California’s Arts Ecosystem USC Radio Group - Overview Format: KDFC’s Mission Classical Public Radio – Non Commercial/Listener Supported + Classical KDFC provides access to great Underwriting/Sponsorship classical music, offers education and insight to this music for a sophisticated Bay Area Music: audience, and supports the local arts Primary focus on Baroque, Classical, and Romantic Eras: 17th Century to community as its voice of the arts and as a Early 20th Century portal to the rich diversity of our performing arts scene • Remainder is late 19th- 20th Century Melodic pieces, Vocal, Contemporary and Movie Music KUSC’s Mission Status: To make classical music and the arts a more • KDFC is The Bay Area’s ONLY important part of more people’s lives by Classical music station presenting high quality classical music programming, and by producing and • KUSC is the nation’s LARGEST presenting programming featuring the arts Classical music station and culture of Southern California USC Radio Group – Delivery/Distribution KDFC KUSC 90.3 FM San Francisco- Berkeley- Oakland 91.5 FM Los Angeles 104.9 FM Silicon Valley: San Jose- The Peninsula 93.7 FM Santa Barbara 89.9 FM Wine Country: Napa - Santa Rosa 99.7 FM San Luis Obispo 90.3 FM South Bay: Los Gatos – Saratoga 88.5 FM Palm Springs 92.5 FM North Bay: Ukiah – Lakeport 91.1 FM Thousand Oaks kdfc.com kusc.org KDFC Mobile App KUSC Mobile App USC Radio Group – Ecosystem USC Radio Group Community Bay Area and SoCal Arts Ecosystem 67,000 Members/Donors 1,500+ Arts Organizations . -

BROWN PAPER How Southern California Public Radio Opened Their Doors to Latinos and Became the Most Listened-To Public Station in Los Angeles: a Case Study

BROWN PAPER How Southern California Public Radio Opened Their Doors to Latinos and Became the Most Listened-to Public Station in Los Angeles: A Case Study RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY PRESENTED BY GINNY Z BERSON EDITED BY SILVIA RIVERA FUNDED BY THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................ 4 Essential Element #1: Unity of Vision and Leadership ............................. 6 Essential Element #2: Community Engagement .................................. 7–8 Essential Element #3: Content and Sound ........................................ 9–10 Essential Element #4: Changing the Culture .................................... 11–12 Results ........................................................................................... 13–14 Conclusion ........................................................................................... 14 Appendix A: Timeline of Key Events ...................................................... 15 Appendix B: Job Description: Multi-Ethnic Outreach Director .......... 15–16 Appendix C: SCPR Public Fora and Events .......................................... 17 Appendix D: Interviews Conducted ....................................................... 18 Appendix E: Initial Reactions to the Case Study ................................... 19 Appendix F: About the Author and Editor............................................. -

Letter from USC Radio

Map of Classical KUSC Coverage KUSC’s Classical Public Radio can be heard in 7 counties, from as far north as San Luis Obispo and as far south as the Mexican border. With 39,000 watts of power, Classical KUSC boasts the 10th most powerful signal in Southern California. KUSC transmits its programming from five transmitters - KUSC-91.5 fm in Los Angeles and Santa Clarita; 88.5 KPSC in Palm Springs; 91.1 KDSC in Thousand Oaks; 93.7 KDB in Santa Barbara and 99.7 in Morro Bay/San Luis Obispo. KUSC Mission To make classical music and the arts a more important part of more people’s lives. KUSC accomplishes this by presenting high quality classical music programming, and by producing and presenting programming that features the arts and culture of Southern California. KUSC supports the goal of the University of Southern California to position USC as a vibrant cultural enterprise in downtown Los Angeles. Page 1 Classical KUSC Table of Contents 1 Map of Classical KUSC Coverage / KUSC Mission 2 Classical KUSC Table of Contents 3-4 Letter from USC Radio President, Brenda Barnes 5 USC Radio Vice President / KUSC Programming Team 6 KUSC Programming On Air-Announcers 7-10 Programming Highlights 2013-14 11 KUSC Online and Tour with the Los Angeles Philharmonic 12 KUSC Interactive 13 KUSC Underwriting 14 KUSC Engineering 15 KUSC Administration 16 USC Radio Board of Councilors 17 Tours with KUSC 18 KUSC Development 19 Leadership Circle 20 Legacy Society 21 KUSC Supports the Arts 22 KUSC Revenue and Expenses Page 2 Letter From USC Radio hen I came to USC Radio almost 17 and covered the arts in the community for W years ago the Coachella Valley was decades. -

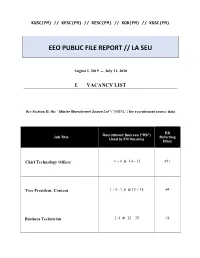

Eeo Public File Report // La Seu

KUSC(FM) // KPSC(FM) // KESC(FM) // KDB(FM) // KDSC(FM) EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT // LA SEU August 1, 2019 -- July 31, 2020 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the “Master Recruitment Source List” (“MRSL”) for recruitment source data RS Recruitment Sources (“RS”) Job Title Referring Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Chief Technology Officer 1 – 4 & 10 – 35 #11 Vice President, Content 1 - 4 , 7, 8 & 12 – 35 #4 Business Technician 1, 4 & 12 – 35 #4 KUSC(FM) // KPSC(FM) // KESC(FM) // KDB(FM) // KDSC(FM 2020 EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT // LA SEU August 1, 2019 - July 31, 2020 Section II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST (“MRSL”) RS # RS Entitled toSource Vacancy Notification?Y/N Referred No. of Interviewees ReportingOver RS by Period Organization Contact Person Address City St. Zip 1 Station Website Kappelman Bill http://www.kusc.org/ Los Angeles CA 90071 N 0 2 USC Recruitment Website http://www.usc.edu/go/jobs Los Angeles CA 90089 N 3 3 Internal Posting Kappelman Bill Los Angeles CA 90071 N 1 4 Word of Mouth // Personal Contacts N 5 5 Internal Promotion N 0 6 LinkedIn.com http://www.linkedin.com/ San Francisco CA N 0 7 Indeed.com (Paid Website) http://www.indeed.com Austin TX 78750 N 2 8 "CURRENT" Newsletter (Paid Ad) https://jobs.current.org/ Washington DC 20016-8122 N 1 9 Koya Leadership Partners (Recruiter) 177 E Colorado Blvd, 2nd Floor Pasadena CA 91105 N 0 10 Stanton Chase (Recruiter) stantonchase.com/office/executive-search-firm-in-los-angeles Santa Monica CA 90401 N 7 11 Glassdoor (Recruiter) glassdoor.com/ Mill Valley CA 94941 N 1 12 Actors Work Program Attn: Human Resources 5757 Wilshire Blvd. -

William Lueth 10 Madrid Court – Danville, CA 94506 Home: (925) 648-4969 [email protected] Cell: (415) 350-5395

William Lueth 10 Madrid Court – Danville, CA 94506 Home: (925) 648-4969 [email protected] Cell: (415) 350-5395 Radio Executive On Air Talent / Program Director / Operations Director / Director of Innovation / General Manager PROFILE 30-year career in public and commercial radio that reflects pioneering experience, record-breaking performance and community impact in classical radio. Additional significant experience understanding audiences in country, rock and news/talk radio formats. Unique and comprehensive industry experience established through the successful transition from working in public radio to commercial radio, then back to public radio. Known for building and motivating cross-functional teams that exceed expectations. National reputation for growing audiences that lead to increased donor and sponsorship support. - Multiple Community Service Awards - Outstanding track record helping to convert a commercial station to a listener-supported station over a short time period - Significant success building audiences in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Phoenix - Recognition and track record of outstanding leadership and cultivating a high-performance culture. _________________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE USC Radio Group, KUSC -LA/KDFC-SF January 2011-present President -KDFC/Vice President-USC Radio Group Assist in creating vision and executing the strategic plan for the radio network in California. Day-to-day supervision of KDFC operation including building a positive workplace culture that achieves consistent and meaningful results. Effectively cultivate relationships and partnerships with key members of the community. Key Achievements Successful relaunch of KDFC as a non-profit station. Revenues in the black within 2.5 years. Drove the strategy and execution for adjusting KUSC's programming philosophy to be more inclusive of a broader audience, resulting in a 20% increase in weekly audience within 18 months and accomplished within a change-resistant culture. -

Worksbroa1casitsacrossamerica

Vol_ III No_ 3 Los Angeles Courity's Only Radio Mogi:emir-se 1998 ILBroa1casitsAmerica.011kAcrossWorks-TIN 4m es It ir 1997KIEARTH'sImmortalized in RearMorgan View 101P 0 Fall Ratings Robot W,,thanks for "Morpoilio'us 101 FM Contents Volume 3, Number 3 February 1998 Listings Talk 21 Sports 22 Soft Hits 22 Adult Standards 23 Classical 23 Public 23 Children's 25 Oldies 26 Features COVER STORY: L.A. Theatre Works 5 KUSC's New Leading Lady 5 Radio Movie 12 lum roles from the pantheon of lit- 14 Robert W. Morgan's retirement rary and theatrical immortals 1997 in L.A. Radio's rear view -mirror 16 continue to attract top Hollywood talents to L.A. Theatre Works 'The 111 Play's the Thing" series. Sparked Depts. 12 years ago by actor Richard Dreyfuss' sugges- tion to founder Susan Loewenberg to put great SOUNDING OFF 4 plays and literature on the radio, the award -win- RADIO ROUNDUP 6 ning series has produced 350 hours of plays, RATINGS 27 novels and short stories. Numerous marquee names are deeply involved, such as Annete Ben- LOONEY POINT OF VIEW 13 ing, John Lithgow, JoBeth Williams, Amy Irving 28 PLAYERS and Alan Alda. Los Angeles Radio Guide Cover design & production by Ben Jacoby 61 Dave White P.O. Box 3680 Publishers Ben Jacoby & Shireen Alafi Santa Monica CA. 90408 Editor -in -Chief Shireen Alafi Voice: (310) 828-7530 Editorial Coordinator/Photographer Sandy Wells Fax (310) 828-0526 Production Director/Photographer Ben Jacoby Subscriptions: $12 Contributing Writers Thom Looney Production Associate Dave White e-mail: [email protected] www. -

FRIDAY RADIO Hands," Roger Williams

Caravan: Spirituals, Gra- with ClairIle Boutlet, edi. Sound,:"AfricanNue ham Jackson Cboir. torofPTarice Observa. Life,"-Ukonit. 6:00 p.m. KB1Q (104.3), Dining tem*,in discussion on Al-10:20 pm. KNOB (97,0), Special FM Highlights Moods:"With These gerian war. Sesitorg "LeGrand Jazz," FRIDAY RADIO Hands," Roger Williams. DM p.m. ICIIHM (04.7), Paul Michel LeGrand, Werth presents a round.11:00 p.m. KNOB (07.01, Jazz FRIDAY. D1C. 4, 1459 112:00 noon ICDWC (98.3), Me 6:00 p.m. KNOB (97.9), Dinner table 'discussion with a Calendar: Music of Her- dies: Les Elgart, "Sophis-, Jazz: "A Date With Della KABC 790itfl 440 K411 - 930 KPOL 1540 Reese." DJ, promotion man, rec. hie/Mann, KALI 100 gFog 1250 K1V 470 KPOP 1020 ticated swing." ord company executive,12:00 midnight KNOB(27.0),' gem 740 1:00 p.m. KOMI (98.7), MtIsle7:00 p.m. li.USC(91.5). Folk publisher,radio station Ivory Tower: "The Big. KFWB 980 KLAC- 570 KRKD Music 1490 KRLA-1110 Sarasate, Capticcio front faraway owner. Shorty Rogers Express"' ((DAY - 1580KGER - 1390KMPC - 710KWI/ 1480 Basque; Ippolitov-Ivanov,1 lends. .10:30 p.m.-KBIQ (104.3), Exotic with the Giants. KIZY . 1190 KGF-I-1230KNX 1070 gWKW 1300 Caucasian Sketches: Ros-17:00 p.m. KFAC (92.3),* AM gpAc -1330 KGIL sini, 'the Barber of Se.' aam), Stereo: Massenet, 1240 KPMC - 1560 KWOW 1400 ville" highlights; Debus. Meditation from "Thais"; KF1 broadcasts news today et 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, sY, "Iberia." Piston, "Incredible Flut- 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11. -

Quarterly Issues/Programs Report

QUARTERLY ISSUES/PROGRAMS REPORT Station (call letters): KDSC (FM) Location (city, state): Thousand Oaks, CA (100% Simulcast of Parent Station KUSC, Los Angeles, CA) For quarter beginning: January 1, 20__ █ April 1, 2017__ July 1, 20__ October 1, 20__ Attached hereto are descriptions of issue-responsive programming broadcast by this station during the reporting period. The listed programs aired on the station during the reporting period on the days and times indicated. Each program regularly provides information or addresses current local issues of concern to viewers in the area where the station is located. LOCAL ISSUES ADDRESSED DURING THE QUARTER The following are local issues of concern to the community. Programs that addressed these issues during this reporting period are listed on the following pages. Local Issue/Concern Brief description of local issue or concern The awareness of local artistic events from producers who share audience with classical music-minded individuals. Coverage of Local Arts To bring the best of classical music, both new and archived recordings to the public-at-large. Exposure to Classical Music The impact of arts and music related curriculums on youth from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds. Education/Children’s Issues PROGRAMS THAT ADDRESS LOCAL ISSUES The following programs that aired during the relevant reporting period regularly address local issues and concerns in the station’s city of license and within its service area. Specific episodes and segments of these programs and the issues they addressed are listed on the following pages. Program Name Schedule Brief Generic Description (Day/Time) (Note whether local, syndicated or network) Arts Alive Saturdays, 8am Locally-produced, 30 minute program about arts and culture in Southern California—includes interviews with local artists and arts community members, interactive Q&A with USC Thornton School of Music Dean, arts news and community arts calendar. -

PRI 2012 Annual Report Mechanical.Ai

PRI 2012 Annual Report Mechanical 11” x 8.375” folded to 5.5” x 8.375” Prepared by See Design, Inc. Christopher Everett 612.508.3191 [email protected] Annual Report 2012 The year of the future. BACK OUTSIDE COVER FRONT OUTSIDE COVER PRI 2012 Annual Report Mechanical 11” x 8.375” folded to 5.5” x 8.375” Dear Friends of PRI, Throughout our history, PRI has distinguished itself as a nimble Prepared by See Design, Inc. organization, able to anticipate and respond to the needs of stations Christopher Everett and audiences as we fulfill our mission: to serve as a distinct content 612.508.3191 source of information, insights and cultural experiences essential to [email protected] living in an interconnected world. This experience served us well in the year just closed, as we saw the pace of change in media accelerate, and faced new challenges as a result. More and more, people are turning to mobile devices to consume news, using them to share, to interact, and to learn even more. These new consumer expectations require that we respond, inspiring us to continue to deliver our unique stories in ways that touch the heart and mind. And to deliver them not only through radio, but also on new platforms. Technology also creates a more competitive environment, enabling access to global news and cultural content that did not exist before. In this environment, PRI worked to provide value to people curious about our world and their place in it. With a robust portfolio of content as a strong foundation for growth, PRI worked to enhance our role as a source of diverse perspectives.