Preschool Curriculum Framework Vol. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Light on the Darkness

Fall 2016 the FlameTHE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY LIGHT ON THE DARKNESS Psychology alumna Jean Maria Arrigo dedicated 10 years of her life to exposing the American Psychological Association’s secret ties to US military interrogation efforts MAKE A GIFT TO THE ANNUAL FUND TODAY the Flame Claremont Graduate University THE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY fellowships play an important role Fall 2016 The Flame is published by in ensuring our students reach their Claremont Graduate University’s Office of Marketing and Communications educational goals, and annual giving 165 East 10th Street Claremont, CA 91711 from our alumni and friends is a ©2016 Claremont Graduate University major contributor. Here are some of VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT our students who have benefitted Ernie Iseminger ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS from the CGU Annual Fund. Max Benavidez EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Andrea Gutierrez “ I am truly grateful for the support that EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ADVANCEMENT COMMUNICATIONS CGU has given me. This fellowship has Nicholas Owchar provided me with the ability to focus MANAGING EDITOR on developing my career.” Roberto C. Hernandez Irene Wang, MBA and MA DESIGNER Shari Fournier-O’Leary in Management DIRECTOR, DESIGN SERVICES Gina Pirtle I received fellowship offers from other ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, INTEGRATED MARKETING “ Alfie Christiansen schools. But the amount of my fellowship ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS from CGU was the biggest one, and Sheila Lefor I think that is one of my proudest DISTRIBUTION MANAGER moments.” Mandy Bennett Akihiro Toyoda, MBA PHOTOGRAPHERS Carlos Puma John Valenzuela If I didn’t have the fellowship, there is William Vasta “ Tom Zasadzinski no way I would have been able to study for a PhD. -

THE LIST Highest Assessed Properties in L.A

DECEMBER 10, 2018 LOS ANGELES BUSINESS JOURNAL 9 NEXT WEEK RADIO STATIONS The Largest City Contractors and Ranked by October 2018 Nielsen Audio ratings THE LIST Highest Assessed Properties in L.A. Rank Station Audience Share Format Profile Sales Managers Top Local Executive • name • October 2018 • format • station owner • name • address • October 2017 • target age group • year founded • title • language • phone KRTH-FM (101.1) 5.0 oldies Entercom Communications Corp. David Severino Jeff Federman 1 5670 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 200 4.5 35-54 1972 Market Manager, General Los Angeles 90036 English Manager (323) 936-5784 KOST-FM (103.5) 4.9 adult contemporary iHeartMedia Inc. John Bassarelli Kevin LeGrett 2 3400 W. Olive Ave., Suite 550 4.5 25-54 1982 President, Market Manager Burbank 91505 English (818) 559-2252 KBIG-FM (104.3) 4.8 hot adult contemporary iHeartMedia Inc. Julie Martzke Kevin LeGrett 3 3400 W. Olive Ave., Suite 550 6.4 25-54 1965 George Flora President, Market Manager Burbank 91505 English (818) 559-2252 KIIS-FM (102.7) 4.2 top 40 hits iHeartMedia Inc. Ari Tsekouras Kevin LeGrett 4 3400 W. Olive Ave., Suite 550 4.5 18-49 1947 Jodi Dewey President, Market Manager Burbank 91505 English (818) 559-2252 KTWV-FM (94.7) 4.2 smooth rhythym and blues Entercom Communications Corp. John Bassanelli Jeff Federman 5670 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 200 4.3 35-54 1987 Market Manager, General Los Angeles 90036 English Manager (323) 937-9283 KCBS-FM (93.1) 3.8 adult hits Entercom Communications Corp. John Bassanelli Jeff Federman 6 5670 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 200 3.6 25-54 2005 Market Manager, General Los Angeles 90036 English Manager (323) 937-9331 KLVE-FM (107.5) 3.8 adult contemporary Univision Communications Jason Strongin Luis Patino 5999 Center Drive, Fourth Floor 3.6 18-49 1972 General Manager Los Angeles 90045 Spanish (310) 846-2868 KFI-AM (640) 3.7 news, talk iHeartMedia Inc. -

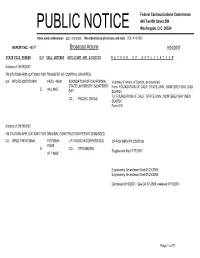

Broadcast Actions 9/24/2007

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46577 Broadcast Actions 9/24/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/18/2007 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR TRANSFER OF CONTROL GRANTED CA BTCED-20070731BYI KAZU 43591 FOUNDATION OF CALIFORNIA Voluntary Transfer of Control, as amended STATE UNIVERSITY, MONTEREY From: FOUNDATION OF CALIF. STATE UNIV., MONTEREY BAY (OLD E 90.3 MHZ BAY BOARD) To: FOUNDATION OF CALIF. STATE UNIV., MONTEREY BAY (NEW CA , PACIFIC GROVE BOARD) Form 316 Actions of: 09/19/2007 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION PERMIT DISMISSED CO BPED-19970728MA 970728MA J P I RADIO INCORPORATED CP FOR NEW FM STATION 87628 E CO , STRASBURG Supplement filed 7/17/2001 97.7 MHZ Engineering Amendment filed 01/21/2005 Engineering Amendment filed 01/25/2005 Dismissed 9/19/2007. See DA 07-3969, released 9/19/2007. Page 1 of 27 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 46577 Broadcast Actions 9/24/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/19/2007 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION PERMIT DISMISSED CO BPED-19980417MI 980417MI CSN INTERNATIONAL CP FOR NEW NCE FM STATION 90910 E CO , STRASBURG 97.7 MHZ SUPPLEMENT FILED 7/19/2001. -

USC Radio Group

The Driving Force and Center of the Bay Area and Southern California’s Arts Ecosystem USC Radio Group - Overview Format: KDFC’s Mission Classical Public Radio – Non Commercial/Listener Supported + Classical KDFC provides access to great Underwriting/Sponsorship classical music, offers education and insight to this music for a sophisticated Bay Area Music: audience, and supports the local arts Primary focus on Baroque, Classical, and Romantic Eras: 17th Century to community as its voice of the arts and as a Early 20th Century portal to the rich diversity of our performing arts scene • Remainder is late 19th- 20th Century Melodic pieces, Vocal, Contemporary and Movie Music KUSC’s Mission Status: To make classical music and the arts a more • KDFC is The Bay Area’s ONLY important part of more people’s lives by Classical music station presenting high quality classical music programming, and by producing and • KUSC is the nation’s LARGEST presenting programming featuring the arts Classical music station and culture of Southern California USC Radio Group – Delivery/Distribution KDFC KUSC 90.3 FM San Francisco- Berkeley- Oakland 91.5 FM Los Angeles 104.9 FM Silicon Valley: San Jose- The Peninsula 93.7 FM Santa Barbara 89.9 FM Wine Country: Napa - Santa Rosa 99.7 FM San Luis Obispo 90.3 FM South Bay: Los Gatos – Saratoga 88.5 FM Palm Springs 92.5 FM North Bay: Ukiah – Lakeport 91.1 FM Thousand Oaks kdfc.com kusc.org KDFC Mobile App KUSC Mobile App USC Radio Group – Ecosystem USC Radio Group Community Bay Area and SoCal Arts Ecosystem 67,000 Members/Donors 1,500+ Arts Organizations . -

BROWN PAPER How Southern California Public Radio Opened Their Doors to Latinos and Became the Most Listened-To Public Station in Los Angeles: a Case Study

BROWN PAPER How Southern California Public Radio Opened Their Doors to Latinos and Became the Most Listened-to Public Station in Los Angeles: A Case Study RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY PRESENTED BY GINNY Z BERSON EDITED BY SILVIA RIVERA FUNDED BY THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................ 4 Essential Element #1: Unity of Vision and Leadership ............................. 6 Essential Element #2: Community Engagement .................................. 7–8 Essential Element #3: Content and Sound ........................................ 9–10 Essential Element #4: Changing the Culture .................................... 11–12 Results ........................................................................................... 13–14 Conclusion ........................................................................................... 14 Appendix A: Timeline of Key Events ...................................................... 15 Appendix B: Job Description: Multi-Ethnic Outreach Director .......... 15–16 Appendix C: SCPR Public Fora and Events .......................................... 17 Appendix D: Interviews Conducted ....................................................... 18 Appendix E: Initial Reactions to the Case Study ................................... 19 Appendix F: About the Author and Editor............................................. -

Letter from USC Radio

Map of Classical KUSC Coverage KUSC’s Classical Public Radio can be heard in 7 counties, from as far north as San Luis Obispo and as far south as the Mexican border. With 39,000 watts of power, Classical KUSC boasts the 10th most powerful signal in Southern California. KUSC transmits its programming from five transmitters - KUSC-91.5 fm in Los Angeles and Santa Clarita; 88.5 KPSC in Palm Springs; 91.1 KDSC in Thousand Oaks; 93.7 KDB in Santa Barbara and 99.7 in Morro Bay/San Luis Obispo. KUSC Mission To make classical music and the arts a more important part of more people’s lives. KUSC accomplishes this by presenting high quality classical music programming, and by producing and presenting programming that features the arts and culture of Southern California. KUSC supports the goal of the University of Southern California to position USC as a vibrant cultural enterprise in downtown Los Angeles. Page 1 Classical KUSC Table of Contents 1 Map of Classical KUSC Coverage / KUSC Mission 2 Classical KUSC Table of Contents 3-4 Letter from USC Radio President, Brenda Barnes 5 USC Radio Vice President / KUSC Programming Team 6 KUSC Programming On Air-Announcers 7-10 Programming Highlights 2013-14 11 KUSC Online and Tour with the Los Angeles Philharmonic 12 KUSC Interactive 13 KUSC Underwriting 14 KUSC Engineering 15 KUSC Administration 16 USC Radio Board of Councilors 17 Tours with KUSC 18 KUSC Development 19 Leadership Circle 20 Legacy Society 21 KUSC Supports the Arts 22 KUSC Revenue and Expenses Page 2 Letter From USC Radio hen I came to USC Radio almost 17 and covered the arts in the community for W years ago the Coachella Valley was decades. -

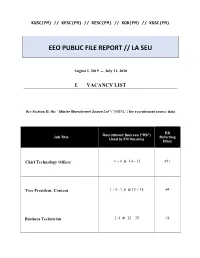

Eeo Public File Report // La Seu

KUSC(FM) // KPSC(FM) // KESC(FM) // KDB(FM) // KDSC(FM) EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT // LA SEU August 1, 2019 -- July 31, 2020 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the “Master Recruitment Source List” (“MRSL”) for recruitment source data RS Recruitment Sources (“RS”) Job Title Referring Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Chief Technology Officer 1 – 4 & 10 – 35 #11 Vice President, Content 1 - 4 , 7, 8 & 12 – 35 #4 Business Technician 1, 4 & 12 – 35 #4 KUSC(FM) // KPSC(FM) // KESC(FM) // KDB(FM) // KDSC(FM 2020 EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT // LA SEU August 1, 2019 - July 31, 2020 Section II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST (“MRSL”) RS # RS Entitled toSource Vacancy Notification?Y/N Referred No. of Interviewees ReportingOver RS by Period Organization Contact Person Address City St. Zip 1 Station Website Kappelman Bill http://www.kusc.org/ Los Angeles CA 90071 N 0 2 USC Recruitment Website http://www.usc.edu/go/jobs Los Angeles CA 90089 N 3 3 Internal Posting Kappelman Bill Los Angeles CA 90071 N 1 4 Word of Mouth // Personal Contacts N 5 5 Internal Promotion N 0 6 LinkedIn.com http://www.linkedin.com/ San Francisco CA N 0 7 Indeed.com (Paid Website) http://www.indeed.com Austin TX 78750 N 2 8 "CURRENT" Newsletter (Paid Ad) https://jobs.current.org/ Washington DC 20016-8122 N 1 9 Koya Leadership Partners (Recruiter) 177 E Colorado Blvd, 2nd Floor Pasadena CA 91105 N 0 10 Stanton Chase (Recruiter) stantonchase.com/office/executive-search-firm-in-los-angeles Santa Monica CA 90401 N 7 11 Glassdoor (Recruiter) glassdoor.com/ Mill Valley CA 94941 N 1 12 Actors Work Program Attn: Human Resources 5757 Wilshire Blvd. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

S \GLES Right Time to Share Your Love with This * BR5-49 Seven Nights to Rock (2:45) WRITERS: E

Reviews & Previews bounty of female solo slow jams currently Yearwood's performance is beautiful and * SPLENDER Yeah, Whatever (3:41) D A N C E bandying for a place on the radio. Great flawless. This is yet another example of PRODUCER: Todd Rundgren production, too, with a sad, sad guitar fol- this fine vocalist's amazing way with a * SOUL SOLUTION FEATURING CAROLYN WRITER: W. Boone lowing along that sounds curiously Asian- song. HARDING Let It Rain (8:421 PUBLISHER: Hit and Run Music Publishing Ltd., ASCAP influenced. Mainstream R &B, this is the PRODUCERS: Bobby Guy, Ernie Lake C2 Records 41936 (CD promo) S \GLES right time to share your love with this * BR5-49 Seven Nights To Rock (2:45) WRITERS: E. Luecke, B. Graziose Columbia imprint C2 Records maintains EIDITED BY CHUCK TAYLOR intriguing singer/songwriter. Meanwhile, PRODUCERS: Jozef Nuyens, Mike Janus PUBLISHERS: Mr. Lake Music/Jelly's Jams L.L.C., ASCAP; its standard of launching a roster of auspi- if you're in search of crossover appeal, WRITER: not listed Nicky's Knacks & Daddy's Tracks/Jumping Beans Songs cious artists with this first rousing single PUBLISHER: not listed BMI check out the Hani smooth and hyper L.L.C., from the New York -based Splender. Arista/Nashville 3162 (CD promo) REMIXERS: John Kano, Johnny Vicious P O P remixes, perfectly suited for those sta- "Yeah, Whatever" is a loud, guitar -satu- The ever -adventuresome, genre -defying Jellybean Recordings 2550 (12 -inch single) off on Deborah Cox's recent rated rocker that begins unsuspectingly 01. -

Rates to Detroit Gets Flak Water Rise

W IN TICKETS: 'BRING IT ON - THE MUSICAL,' GO TO HOMETOWNLIFE.COM TO ENTER CANTON GANNETT COMPANY 'M IS L E D ' Jonathan Stanley recalls his Detroit roots in new film ENTERTAINMENT, B5 THURSDAY, MARCH 20, 2014 • hometownlife.com Water rates to rise; Detroit gets flak battled D etroit Water and be slammed as DWSD wres every three-month billing “I t h in k Township officials Sewerage Department. tles with infrastructure ex period w ill pay quarterly bills It signals Canton's firs t rate penses and legacy costs. o f $358 - or just over $1,400 a th e y ’re a bemoan increase hike since 2011 after the town Township Treasurer Melis year. b u n c h o f ship board fo r the last two sa McLaughlin indicated sim i To be sure, Canton rate By Darrell Clem years chose to absorb cost lar concerns about long-term hikes are fa r less than in incompetent Sta« Writer increases imposed by DWSD, rate hikes. creases that topped 20 percent bo o b s w h o which came under attack from “ I think we could be looking in 2008, when township o ffi A united Canton Tbwnship TVustee John Anthony. at some very d ifficu lt things cials passed DWSD costs onto d o n ’t h a v e a c lu e to Board o f Trustees reached a " I think they’re a bunch of down the road o f which we consumers and added local w hat’s going on. ” consensus Hiesday night to incompetent boobs who don't w ill have no control," she said.