Welfa Are Ext Ension Prote by Loc Ection: Cal Stat Surat Te and S Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

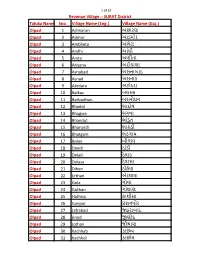

Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 1

1 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 1 Achharan અછારણ Olpad 2 Admor આડમોર Olpad 3 Ambheta અંભેટા Olpad 4 Andhi આંઘી Olpad 5 Anita અણીતા Olpad 6 Ariyana અરીયાણા Olpad 7 Asnabad અસનાબાદ Olpad 8 Asnad અસનાડ Olpad 9 Atodara અટોદરા Olpad 10 Balkas બલકસ Olpad 11 Barbodhan બરબોઘન Olpad 12 Bhadol ભાદોલ Olpad 13 Bhagwa ભગવા Olpad 14 Bhandut ભાંડુત Olpad 15 Bharundi ભારં ડી Olpad 16 Bhatgam ભટગામ Olpad 17 Bolav બોલાવ Olpad 18 Dandi દાંડી Olpad 19 Delad દેલાડ Olpad 20 Delasa દેલાસા Olpad 21 Dihen દીહેણ Olpad 22 Erthan એરથાણ Olpad 23 Gola ગોલા Olpad 24 Gothan ગોથાણ Olpad 25 Hathisa હાથીસા Olpad 26 Isanpor ઇશનપોર Olpad 27 Jafrabad જાફરાબાદ Olpad 28 Jinod જીણોદ Olpad 29 Jothan જોથાણ Olpad 30 Kachhab કાછબ Olpad 31 Kachhol કાછોલ 2 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 32 Kadrama કદરામા Olpad 33 Kamroli કમરોલી Olpad 34 Kanad કનાદ Olpad 35 Kanbhi કણભી Olpad 36 Kanthraj કંથરાજ Olpad 37 Kanyasi કન્યાસી Olpad 38 Kapasi કપાસી Olpad 39 Karamla કરમલા Olpad 40 Karanj કરંજ Olpad 41 Kareli કારલે ી Olpad 42 Kasad કસાદ Olpad 43 Kasla Bujrang કાસલા બજુ ઼ રંગ Olpad 44 Kathodara કઠોદરા Olpad 45 Khalipor ખલીપોર Olpad 46 Kim Kathodra કીમ કઠોદરા Olpad 47 Kimamli કીમામલી Olpad 48 Koba કોબા Olpad 49 Kosam કોસમ Olpad 50 Kslakhurd કાસલાખુદદ Olpad 51 Kudsad કુડસદ Olpad 52 Kumbhari કુભારી Olpad 53 Kundiyana કુદીયાણા Olpad 54 Kunkni કુંકણી Olpad 55 Kuvad કુવાદ Olpad 56 Lavachha લવાછા Olpad 57 Madhar માધ઼ ર Olpad 58 Mandkol મંડકોલ Olpad 59 Mandroi મંદરોઇ Olpad 60 Masma માસમા Olpad 61 Mindhi મીઢં ીં Olpad 62 Mirjapor મીરઝાપોર 3 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. -

Lok Sabha ___ Synopsis of Debates

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Monday, March 11, 2013 / Phalguna 20, 1934 (Saka) ______ OBITUARY REFERENCE MADAM SPEAKER: Hon. Members, it is with great sense of anguish and shock that we have learnt of the untimely demise of Mr. Hugo Chavez, President of Venezuela on the 5th March, 2013. Mr. Hugo Chavez was a popular and charismatic leader of Venezuela who always strived for uplifting the underprivileged masses. We cherish our close relationship with Venezuela which was greatly strengthened under the leadership of President Chavez. We deeply mourn the loss of Mr. Hugo Chavez and I am sure the House would join me in conveying our condolences to the bereaved family and the people of Venezuela and in wishing them strength to bear this irreparable loss. We stand by the people of Venezuela in their hour of grief. The Members then stood in silence for a short while. *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 (i) SHRI ANTO ANTONY laid a statement regarding need to check smuggling of cardamom from neighbouring countries. (ii) SHRI M. KRISHNASSWAMY laid a statement regarding construction of bridge or underpass on NH-45 at Kootterapattu village under Arani Parliamentary constituency in Tamil Nadu. (iii) SHRI RATAN SINGH laid a statement regarding need to set up Breeding Centre for Siberian Cranes in Keoladeo National Park in Bharatpur, Rajasthan. (iv) SHRI P.T. THOMAS laid a statement regarding need to enhance the amount of pension of plantation labourers in the country. (v) SHRI P. VISWANATHAN laid a statement regarding need to set up a Multi Speciality Hospital at Kalpakkam in Tamil Nadu to treat diseases caused by nuclear radiation. -

School Vacancy Report

School Vacancy Report ગણણત/ સામાજક ાથિમકની ભાષાની િવાનન િવાનની ખાલી ખાલી પે સેટર શાળાનો ◌ી ખાલી ખાલી જલો તાલુકા ડાયસ કોડ શાળાનું નામ માયમ પે સેટર જયા જયા ડાયસ કોડ જયા જયા (ધોરણ ૧ (ધોરણ ૬ (ધોરણ (ધોરણ ૬ થી ૫) થી ૮) ૬ થી ૮) થી ૮) Surat Bardoli 24220108203 Balda Khadipar 24220108201 Balda Mukhya 0 0 1 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220100701 Rajwad 24220108201 Balda Mukhya 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220103002 Bardoli Kanya 24220103001 Bardoli Kumar 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220105401 Bhuvasan 24220105401 Bhuvasan 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102101 Haripura 24220101202 Kadod 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 0 0 2 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102301 Surali 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 0 0 1 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102305 Surali Hat Faliya 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 0 0 1 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220106801 Vadoli 24220106401 Tarbhon 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220103801 Mota 24220103601 Umarakh 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220202401 Bhatlai 24220202201 Damka 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220202801 Junagan 24220202201 Damka 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220202301 Vansva 24220202201 Damka 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220205904 Haidarganj 24220205901 Sachin 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220206302 Kanakpur GHB 24220205901 Sachin 0 1 0 0 ગુજરાતી Page No : 1 School Vacancy Report Surat Choryasi 24220206301 Kanakpur Hindi Med 24220205901 Scahin 0 1 2 0 હદ Surat Choryasi 24220208001 Paradi Kande 24220205901 Sachin 0 0 0 2 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220206001 Talangpur 24220205901 -

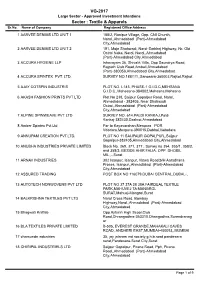

Sector : Textile & Apparels VG-2017

VG-2017 Large Sector - Approved Investment Intentions Sector : Textile & Apparels Sr.No. Name of Company Registered Office Address 1 AARVEE DENIMS LTD UNIT 1 188/2, Ranipur Village, Opp. CNI Church, Narol,,Ahmadabad (Part)-Ahmedabad City,Ahmedabad 2 AARVEE DENIMS LTD UNIT 2 191, Moje Shahwadi, Narol-Sarkhej Highway, Nr. Old Octroi Naka, Narol, Narol,,Ahmadabad (Part)-Ahmedabad City,Ahmedabad 3 ACCURA HYGIENE LLP Ishavayam 36, Shivalik Villa, Opp Saundrya Road, Rajpath Club Road,Ambali,Ahmadabad (Part)-380058,Ahmedabad City,Ahmedabad 4 ACCURA SPINTEX PVT. LTD. SURVEY NO.188/1/1,,Sanosara-360003,Rajkot,Rajkot 5 AJAY COTSPIN INDUSTRIS PLOT NO. I-143, PHASE-1 G.I.D.C,MEHSANA G.I.D.C.,Mahesana-384002,Mehsana,Mehsana 6 AKASH FASHION PRINTS PVT LTD Plot No 238, Saijpur Gopalpur Road, Narol, Ahmedabad - 382405, Near Shahwadi Octroi,,Ahmadabad (Part)-Ahmedabad City,Ahmedabad 7 ALPINE SPINWEAVE PVT LTD SURVEY NO. 614,PALDI KANKAJ,Paldi Kankaj-382430,Daskroi,Ahmedabad 8 Amber Spintex Pvt Ltd Por to Kayavarohan,Menpura POR Vdodara,Menpura-390015,Dabhoi,Vadodara 9 ANNUPAM CREATION PVT.LTD. PLOT NO 11 SAIJPAUR GOPALPUR,,Saijpur Gopalpur-382405,Ahmedabad City,Ahmedabad 10 ANUBHA INDUSTRIES PRIVATE LIMITED Block No. 369, 371, 377 , Survey no 354, 355/1, 358/2, and 358/3, BESIDE AHIR FALIA, OPP. DHOBIL MIL,,-,Surat 11 ARNAV INDUSTRIES 302 Isanpur, Isanpur, Vatwa Road;b/H Aaradhana Proces, Isanpur,,Ahmadabad (Part)-Ahmedabad City,Ahmedabad 12 ASSURED TRADING POST BOX NO 116079,DUBAI CENTRAL,DUBAI,-, 13 AUTOTECH NONWOVENS PVT LTD PLOT NO 37 37A 38 38A FAIRDEAL -

Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES* (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______ SUBMISSION BY MEMBERS Re: Farmers facing severe distress in Kerala. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI RAJ NATH SINGH) responding to the issue raised by several hon. Members, said: It is not that the farmers have been pushed to the pitiable condition over the past four to five years alone. The miserable condition of the farmers is largely attributed to those who have been in power for long. I, however, want to place on record that our Government has been making every effort to double the farmers' income. We have enhanced the Minimum Support Price and did take a decision to provide an amount of Rs.6000/- to each and every farmer under Kisan Maan Dhan Yojana irrespective of the parcel of land under his possession and have brought it into force. This * Hon. Members may kindly let us know immediately the choice of language (Hindi or English) for obtaining Synopsis of Lok Sabha Debates. initiative has led to increase in farmers' income by 20 to 25 per cent. The incidence of farmers' suicide has come down during the last five years. _____ *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 1. SHRI JUGAL KISHORE SHARMA laid a statement regarding need to establish Kendriya Vidyalayas in Jammu parliamentary constituency, J&K. 2. DR. SANJAY JAISWAL laid a statement regarding need to set up extension centre of Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari (Bihar) at Bettiah in West Champaran district of the State. 3. SHRI JAGDAMBIKA PAL laid a statement regarding need to include Bhojpuri language in Eighth Schedule to the Constitution. -

Census of India 2001

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES-25 GUJARAT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Part XII-A & B SURAT DISTRICT PART II VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY -¢-- VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT ~.,~ &~ PEOPLE ORIENTED Jayant Parimal of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations, Gujarat © Govj!mment of India Copyright Data Product Code 24-034-2001- Census-Book Contents Pages Foreword xi Preface xiii Acknowledgements xv District Highlights -2001 Census xvii Important Statistics in the District xix Ranking of Talukas in the District XXI Statements 1-9 Statement 1: Name of the Headquarters of the DistrictlTaluka, their Rural-Urban status xxiv and distance from District Headquarters, 2001 Statement 2: Name of the Headquarters of the District/TalukalC.D.Block, their Rural- xxiv Urban status and distance from District Headquarters, 2001 Statement 3: Population of the District at each Census from 1901 To 2001 xxv Statement 4: Area, Number of VillagesIT owns and Population in District and Taluka,2001 xxvi Statement 5: Taluka IC.D.Blockwise Number of Villages and Rural Pop)llation, 2001 xxix Statement 6.: Population of Urban Agglomerations I Towns, 2001 xxix Statement 7: Villages with Population of 5,000 and above at Taluka I C.D.Block Level as xxx per 2001 Census and amenities available Statement 8: Statutory Towns with Population less than 5,000 as per 2001 Census and xxxiii amenities available Statement 9: Houseless and Ins~itutional Population of Talukas, Rural and Urban, 2001 XXXlll Analytical Note (i) History and Scope of the DisL ________ s Handbook 3 (ii) Brief History of the District 4 (iii) Administrative Set Up 6 (iv) Physical Features 8 (v) Census Concepts 19 (vi) Non-Census Concepts 25 (vii) 2001 Census Findings - Population, its distribution 30 Brief analysis of PCA data Brief analysis of the Village Directory and Town Directory data Brief analysis of the data on Houses and Household amenities House listing Operations, Census of India 2001 (viii) . -

DENA BANK.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE South ANDAMAN Andaman,Village &P.O AND -BambooFlat(Near bambooflat NICOBAR Rehmania Masjid) BAMBOO @denaban ISLAND ANDAMAN Bambooflat ,Andaman-744103 FLAT BKDN0911514 k.co.in 03192-2521512 non-MICR Port Blair,Village &P.O- ANDAMAN Garacharma(Near AND Susan garacharm NICOBAR Roses,Opp.PHC)Port GARACHAR a@denaba ISLAND ANDAMAN Garacharma Blair-744103 AMA BKDN0911513 nk.co.in (03192)252050 non-MICR Boddapalem, Boddapalem Village, Anandapuram Mandal, ANDHRA Vishakapatnam ANANTAPU 888642344 PRADESH ANANTAPUR BODDAPALEM District.PIN 531163 R BKDN0631686 7 D.NO. 9/246, DMM GATE ANDHRA ROAD,GUNTAKAL – 08552- guntak@denaba PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL 515801 GUNTAKAL BKDN0611479 220552 nk.co.in 515018302 Door No. 18 slash 991 and 992, Prakasam ANDHRA High Road,Chittoor 888642344 PRADESH CHITTOOR Chittoor 517001, Chittoor Dist CHITTOOR BKDN0631683 2 ANDHRA 66, G.CAR STREET, 0877- TIRUPA@DENA PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATHI TIRUPATHI - 517 501 TIRUPATI BKDN0610604 2220146 BANK.CO.IN 25-6-35, OPP LALITA PHARMA,GANJAMVA ANDHRA EAST RI STREET,ANDHRA 939474722 KAKINA@DENA PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA PRADESH-533001, KAKINADA BKDN0611302 2 BANK.CO.IN 1ST FLOOR, DOOR- 46-12-21-B, TTD ROAD, DANVAIPET, RAJAHMUNDR ANDHRA EAST RAJAMUNDRY- RAJAHMUN 0883- Y@DENABANK. PRADESH GODAVARI RAJAHMUNDRY 533103 DRY BKDN0611174 2433866 CO.IN D.NO. 4-322, GAIGOLUPADU CENTER,SARPAVAR AM ROAD,RAMANAYYA ANDHRA EAST RAMANAYYAPE PETA,KAKINADA- 0884- ramanai@denab PRADESH GODAVARI TA 533005 KAKINADA BKDN0611480 2355455 ank.co.in 533018003 D.NO.7-18, CHOWTRA CENTRE,GABBITAVA RI STREET, HERO HONDA SHOWROOM LINE, ANDHRA CHILAKALURIPE CHILAKALURIPET – CHILAKALU 08647- chilak@denaban PRADESH GUNTUR TA 522616, RIPET BKDN0611460 258444 k.co.in 522018402 23/5/34 SHIVAJI BLDG., PATNAM 0836- ANDHRA BAZAR, P.B. -

01-12-2014 11:46:15Am Ews-1

SURAT URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Result of Draw Under Mukhya Mantri GRUH Yojna Selected List Scheme : EWS-1 - VESU Date : 01-12-2014 11:46:15AM Sr. Appl. No. Name & Address Category Flat No. No. GODAVLE BALMUKUND HIRAMAN 1 E13255 Defence EWS1/A3/701 312-MANDARWAJA ,FIREMAN ,RING RD ,SURAT-395002 MENDAPARA HARESHKUMAR VALLABHBHA 2 E9668 Defence EWS1/A3/305 FLAT NO 401,BALAJI FLATS,OPP JIVAN JYOT CINEMA UDHNA,SURAT-395007 TIWARI SHYAM MOHAN VMASHANKAR 3 E7635 Defence EWS1/A2/902 D-16 , STAFF QUARTER S.V.N.I.T,CAMPUS ICHHANATH ,SURAT,SURAT-395007 PANDEY VINOD JAGDISHBHAI 4 E25229 Defence EWS1/A1/403 205 , SARSWAT NAGAR SOC,VESU,SURAT,SURAT-395007 YADAV SUDARSHAN RAJARAM 5 E5349 Defence EWS1/A3/505 126 KAILASHNAGAR SOC.,DINDOLI,-,SURAT-394210 SIKARWAR CHARANSINGH SAMANTSINGH 6 E7219 Defence EWS1/A2/708 402 PRAMUKH DOCTER HOUSE,NEAR TVS POINT,PUNA KUMBHARIYA ROAD PARVAT PATIYA,SURAT-395010 7 E16973 BETKAR MARUTI BHAV Defence EWS1/A3/807 1/2220-29,KUWA VADI OPP NATINAL AUTO GAREJ,NANPURA,SURAT-395001 BADGUJAR YASHVANT SITARAM 8 E14354 Defence EWS1/A2/905 128 DAXESHWAR NAGAR,GHB MAIN RD.,PANDESARA,SURAT-394221 9 E22676 BANDUKWALA SHANTILAL DAMODARDAS Defence EWS1/A1/606 1/611 , MONA APPT NI PACHAL,KHARVAWAD ,NANPURA,SURAT-395001 SAIYAD SHABANABI AIYUB 10 E5677 Defence EWS1/A3/805 89 NEHARUNAGAR ZUPADPATTI,FALWADI BHARIMATA ROAD,SURAT,SURAT-395004 Printed on Date 01-12-2014 11:48:25 12706553 Page 1 of 25 SURAT URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Result of Draw Under Mukhya Mantri GRUH Yojna Selected List Scheme : EWS-1 - VESU Date : 01-12-2014 11:46:24AM Sr. -

Information Memorandum

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM Industrial Property at Pardi, Gujarat ASCC ASCC Transaction Overview Ascent Supply Chain Consultants Pvt. Ltd. (ASCC) is appointed as a consultant for the sale of Freehold Industrial property comprising land - admeasuring approximately 13,760 Sq. Mtrs. (3.4 Acres) and with built up area about 38,000 Sq. Ft. It is a well maintained property. The property is located at Village – Umarsadi Desaiwad, Taluka – Pardi, District – Valsad on NH-8. Unit is only 1 Km from NH – 8 Mumbai – Ahmedabad. ASCC 2 Property Location • The captioned property is situated at Village Pardi, Umarsadi Desaiwad Road, Killa Pardi. Pardi is a Taluka situated in Valsad District in the Indian State of Gujarat. It is located 14 Kms towards South from District Headquarters Valsad. It is near to the Daman & Diu State Border & Arabian Sea. Pardi, Valsad, Daman and Diu and Vapi are the adjoining Cities. • The city of Vapi, a large industrial township for small-scale industries is roughly 16 Kms South of Pardi Town. Pardi has its own industrial zone which is governed by GIDC and caters mainly to the Textile Industry. • Udvada, the Holy Town for Parsis is about 7 Kms South of Pardi Town. • Daman & Dadra Nagar Haveli is a famous tourist destination which is about 19 Kms South of Pardi Town. ASCC 3 Location Map Property Location ASCC 4 Property Overview Plot Area 13,760 Sq. Mtrs. (Industrial) 38,000 Sq. Ft. approx (Industrial Building – RCC Construction & Built up Area Shed) Land + Structure (Shed and RCC), All fitting, furniture, fixtures, Offer includes -

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS of DEBATES (Proceedings Other Than

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Tuesday, July 15, 2014 / Ashadha 24, 1936 (Saka) ______ STATEMENT BY MINISTER Re: Reported meeting of an Indian journalist with Hafiz Saeed in Pakistan. THE MINISTER OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS AND MINISTER OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS (SHRIMATI SUSHMA SWARAJ): On the issue which was raised yesterday in the House, I, with utmost responsibility and categorically and equivocally would like to inform this House that the Government of India has no connection to the visit by Shri Ved Prakash Vaidik to Pakistan or his meeting with Hafiz Saeed there. Neither before leaving for Pakistan nor at his arrival there, he informed the Government that he was to meet Hafiz Saeed there. This was his purely private visit and meeting. It has been alleged here that he was somebody‟s emissary, somebody‟s disciple or the Government of India had facilitated the meeting. This is totally untrue as well as unfortunate. I would like to reiterate that the Government of India has no relation to it whatsoever. *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 (i) SHRI BHARAT SINGH laid a statement regarding need to start work on multipurpose project for development of various facilities in Ballia Parliamentary constituency, Uttar Pradesh. (ii) SHRI BHANU PRATAP SINGH VERMA laid a statement regarding need to extend Shram Shakti Express running between New Delhi to Kanpur upto Jhansi. (iii) SHRIMATI JAYSHREEBEN PATEL laid a statement regarding need to expedite development of National Highway No. 228 declared as a Dandi Heritage route. (iv) SHRI DEVJI M. PATEL laid a statement regarding need to provide better railway connectivity in Jalore Parliamentary Constituency in Rajasthan. -

BREIF INDUSTRIAL PROFILE of SURAT DISTRICT MSME- DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE GOVERNMENT of INDIA Harsiddh Chambers, 4Th Floor, Ashra

BREIF INDUSTRIAL PROFILE OF SURAT DISTRICT MSME- DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Harsiddh Chambers, 4th Floor, Ashram Road, Ahmedabad-380014 Ph: 079-27543147/27544248 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.msmediahmedabad.gov.in 1. Brief Industrial Profile of Surat District 1. General Characteristics of the District 1.1 Location & Geographical Area: Surat is located on the Southern part of Gujarat between 21 to 21.23 degree Northern latitude and 72.38 to 74.23 Eastern longitude. 1.2 Topography: Being located on the Southern part of Gujarat between 21‟ to 21.23‟ degree Northern latitude and 72.38‟ to 74.23‟ Eastern longitude Surat is the second largest commercial hub in the State. The district is divided into ten revenue tehsils namely Choryasi, Palsana, Kamrej, Bardoli, Olpad, Mangrol, Mandvi and Surat city are the major developed tehsils in the district. Surat is mainly known for its textiles and diamond cutting & processing industries. Nowadays, It is emerging as a potential hub for IT\TeS sector in Gujarat. Hajira and Magdalla Ports in the district provide logistic support to the industrial operations min the state with foreign countries. 1.3 Availability of Minerals: A) Description: Surat is the second largest producer of lignite in Gujarat, which accounted for 19 % (17, 21,333 MT) of the total production (90,96,438 MT) of lignite in the state during 2005-06. 2. There are lignite based Thermal Power Stations producing and transmitting electric power, roofing tiles factories, stone ware pipes and drainage pipe factories and glass factories are functioning in mineral based industries on medium and large scale in the district. -

Common Effluent Treatment Plant)-A Case Study of Pandesara, Surat

International Journal of Current Engineering and Technology E-ISSN 2277 – 4106, P-ISSN 2347 – 5161 ©2018 INPRESSCO®, All Rights Reserved Available at http://inpressco.com/category/ijcet Research Article Performance Study of CETP (Common Effluent Treatment Plant)-A Case Study of Pandesara, Surat Anjali M. Tandel#* and Mitali A. Shah# #Civil Engineering Department SCET, Surat, India Received 01 Nov 2017, Accepted 01 Jan 2018, Available online 04 Jan 2018, Vol.8, No.1 (Jan/Feb 2018) Abstract Water is life sustaining element subjected to pollution by human being in the name of industrial development. Global trends such as urbanization and industrialization have increased the demand for fresh water. The developing human societies are heavily dependent upon the availability of water with suitable quality and in adequate quantity for variety of uses. Rapid industrialization is adversely impacting the environment globally. Inappropriate management of industrial wastewater is one of the major environmental problems in India. Many small and medium scale industries cannot afford to have their own effluent treatment facilities which emphasizes on having a common effluent treatment plant to treat the heterogeneous effluent coming out of various sectors. Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETP) for Textile industry is considered as one of the viable solution for small to medium enterprises for effective wastewater treatment. An effluent treatment plant operating on physical, chemical and biological treatment method with average waste water in flow of 100MLD has been considered for case study. The wastewater was analyzed for the major water quality parameters, such as pH, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Total suspended solid (TSS) and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS).