4 Irena Troupová

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Themenkatalog »Musik Verfolgter Und Exilierter Komponisten«

THEMENKATALOG »Musik verfolgter und exilierter Komponisten« 1. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis Babin, Victor Capriccio (1949) 12’30 3.3.3.3–4.3.3.1–timp–harp–strings 1908–1972 for orchestra Concerto No.2 (1956) 24’ 2(II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)–4.2.3.1–timp.perc(3)–strings for two pianos and orchestra Blech, Leo Das war ich 50’ 2S,A,T,Bar; 2(II=picc).2.corA.2.2–4.2.0.1–timp.perc–harp–strings 1871–1958 (That Was Me) (1902) Rural idyll in one act Libretto by Richard Batka after Johann Hutt (G) Strauß, Johann – Liebeswalzer 3’ 2(picc).1.2(bcl).1–3.2.0.0–timp.perc–harp–strings Blech, Leo / for coloratura soprano and orchestra Sandberg, Herbert Bloch, Ernest Concerto Symphonique (1947–48) 38’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(3):cyms/tam-t/BD/SD 1880–1959 for piano and orchestra –cel–strings String Quartet No.2 (1945) 35’ Suite Symphonique (1944) 20’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc:cyms/BD–strings Violin Concerto (1937–38) 35’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(2):cyms/tgl/BD/SD– harp–cel–strings Braunfels, Walter 3 Chinesische Gesänge op.19 (1914) 16’ 3(III=picc).2(II=corA).3.2–4.2.3.1–timp.perc–harp–cel–strings; 1882–1954 for high voice and orchestra reduced orchestraion by Axel Langmann: 1(=picc).1(=corA).1.1– Text: from Hans Bethge’s »Chinese Flute« (G) 2.1.1.0–timp.perc(1)–cel(=harmonium)–strings(2.2.2.2.1) 3 Goethe-Lieder op.29 (1916/17) 10’ for voice and piano Text: (G) 2 Lieder nach Hans Carossa op.44 (1932) 4’ for voice and piano Text: (G) Cello Concerto op.49 (c1933) 25’ 2.2(II=corA).2.2–4.2.0.0–timp–strings -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

Pražské Jaro Gennadij Rožděstvenskij Festival Opera 2007 Státní Opera Stuttgart XVI

HUDEBNÍ ROZHLEDY 05 2007 | ročník 60 | cena 40 Kč Pražské jaro Gennadij Rožděstvenskij Festival Opera 2007 Státní opera Stuttgart XVI. FESTIVAL MITTE EUROPA 2007 Patroni ANGELA MERKEL MIREK TOPOLÁNEK GEORG MILBRADT kancléřka Spolkové republiky Německo předseda vlády České republiky předseda vlády Svobodného státu Sasko »Variatio delectat · Rozmanitost potěší« více než 60 festivalových měst a obcí v příhraničním česko-německém regionu malebné kostely a kláštery · romantické zámky a hrady · nostalgická lázeňská místa klasická hudba klezmer jazz lidová hudba výstavy · workshopy a symposia · Divadelní podzim www.festival-mitte-europa.com · [email protected] Festival Mitte Europa, nám. krále Jiřího z Poděbrad 43, 350 02 Cheb, tel.: 354 436 941 Dům kultury / SFT, Mírové nám. 2950, 415 28 Teplice, tel.: 775 919 339 umělecký ředitel Thomas Thomaschke Ministerstvo kultury České republiky Mediální partneři obsah Závěrečný koncert letošního Mezinárodního hudebního festi- ROZHOVORY valu Pražské jaro, o jehož celkové dramaturgii přinášíme v úvodu 3 · Pražské jaro 2007 rozhovor s ředitelem festivalu Romanem Bělorem, bude dirigo- 6 · Gennadij Rožděstvenskij vat světově proslulý Gennadij Rožděstvenskij. Naposledy zavítal do Prahy společně s manželkou, vynikající klavíristkou Viktorií UDÁLOSTI Postnikovovou a synem, talentovaným houslistou Alexandrem 8 · Festival Opera 2007 21. února, kdy vystoupili ve Smetanově síni s Pražskými symfo- niky, s nimiž se – tentokrát však pouze sám – představí i na letoš- FESTIVALY, KONCERTY ním festivalu. A -

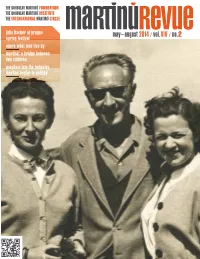

May–August 2014/ Vol.XIV / No.2

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE MR julia fischer at prague may–august 2014 / vol.XIV / no.2 spring festival opera what men live by martinů: a bridge between two cultures peephole into the bohuslav martinů center in polička BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INTHEYEAR OFCZECH MUSIC & BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ DAYS contents 2014 3 PROLOGUE 4 14+15+16 SEPTEMBER 2014 9.00 pm . Lesser Town of Prague Cemetery 5 Eva Blažíčková – choreographer MARTINŮ . The Bouquet of Flowers, H 260 6 7 OCTOBER 2014 . 8.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S SOLDIER Concert in the occasion of 100th anniversary of Josef Páleníček’s birth Smetana Trio, Wenzel Grund – clarinet AND DANCER MARTINŮ . Piano Trio No 2, H 327 OLGA JANÁČKOVÁ (+ PÁLENÍČEK, JANÁČEK) THE SOLDIER AND THE DANCER IN PLZEŇ 2 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . National Theatre, Prague EVA VELICKÁ Ballet ensemble of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre, Nataša Novotná – choreographer 8 MARTINŮ . The Strangler, H 314 (+ SMETANA, JANÁČEK) GEOFF PIPER MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 5.00 pm . Hall of Prague Conservatory Concert Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music – programme see page 3 10 JULIA FISCHER AT PRAGUE SPRING BOHUSLAV . MARTINU DAYS FESTIVAL FRANK KUZNIK 30 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague TWO STARS ENCHANT THE RUDOLFINUM Concert of the winners of Bohuslav Martinů Competition PRAVOSLAV KOHOUT in the Category Piano Trio and String Quartet 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 7.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague 12 Kühn Children's Choir, choirmasters: Jiří Chvála, Petr Louženský WHAT MEN LIVE BY Panocha Quartet members (Jiří Panocha, Pavel Zejfart – violin, GREGORY TERIAN Miroslav Sehnoutka – viola), Jan Kalfus – organ, Petr Kostka – recitation, Ivan Kusnjer – baritone, Daniel Wiesner – piano MARTINŮ . -

BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, Colored Drawing from a Scrapbook

A POCKET GUIDE TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, colored drawing from a scrapbook 1 FROM POLIČKA TO PRAGUE 1890 — 1922 2 On The Polička Tower 1.1 Bohuslav came into the world in a tiny room on the gallery of the church tower where his father, Ferdinand Martinů, apart from being a shoemaker, also carried out a unique job as the tower- keeper, bell-ringer and watchman. Polička - St. James´ Church and the Bastion “On December 8th, the crow brought us a male, a boy, and on Dec. 14th 1.2 A Loving Family he was baptized as It was the mother who energetically took charge of the whole family. She was Bohuslav Jan.” the paragon of order and discipline: strict, pious – a Roman Catholic, naturally, as (The composer’s father were most inhabitants of this hilly region. made this entry in the Of course, she loved all of her children. With Ferdinand Martinů she had fi ve; and family chronicle.) the youngest and probably the most coddled was Bohuslav, born to the accom- paniment of the festive ringing of all the bells, as the town celebrated on that day the holiday of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. To be born high above the ground, almost within the reach of the sky, seemed in itself to promise an exceptional life ahead. Also his brother František and his sister Marie had their own special talents. František graduated from art school and made use of his artistic skills above all 3 as a restorer and conservator of church art objects in his homeland as well as abroad. -

Neeme Järvi Bohuslav Martinů, at Home in Vieux-Moulin, France, 1937 Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library / © Památník Bohuslava Martinů Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959)

ˆ ˆ Suites from ‘Spalícek’ Rhapsody-Concerto Mikhail Zemtsov viola Estonian National Symphony Orchestra Neeme Järvi © Památník Bohuslava Martinů / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Bohuslav Martinů,athomein Bohuslav Vieux-Moulin, France, 1937 France, Vieux-Moulin, Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959) Suites from Špalíček’, H 214 (1931 – 32, revised 1937, 1940) (Chapbook) Opera-ballet in Three Acts Liidia Ilves piano Suite No. 1, H 214A* 22:29 1 I Prelude (Předehra). Poco allegro 1:22 2 II Dance with the Hare (Tanec se zajícem). Allegretto poco moderato 1:31 III In the Magician’s Palace (V paláci černokněžníkově) 3 Dance of the Shadows (Tanec stínů). Moderato – Poco allegro – Allegro – 2:18 4 Dance of the Lion (Tanec lva). Moderato – 1:15 5 Dance of the Sparrow-hawk (Tanec krahujce). Allegro vivo – 0:37 6 Dane of the Little Mouse (Tanec malé myšky). Allegretto – Poco vivo – 1:19 7 Change of Scene and Dance of Puss in Boots (Proměna a tanec Kocoura v botách). Lento – Allegretto – Poco vivo 1:42 8 IV Cinderella’s Ball at the Palace (Popelčin ples na zámku). Lento – Moderato – Allegro moderato – Poco vivo – Tempo I 9:32 9 V The Wedding Polka (Svatební Polka). Moderato – Poco vivo – Meno – Allegro – Poco vivo – Più vivo – Allegro vivo 2:33 3 Suite No. 2, H 214B* 22:24 10 I Dance of the Devils (Tanec čertů). Allegro 2:55 11 II The Shoemaker’s Capricious Patron (Ševcova rozmarná zákaznice). Poco vivo 1:22 12 III The Market – Dance of the Bumble-bee (Trh – Tanec čmeláka). Moderato – Moderato (Un poco più vivo) 3:01 IV The Rescue of the Princess (Vysvobození princeznino) 13 1. -

Supraphon Classical Music Catalogue 2019

s cla ssical music cat alogue 2020 Pavel Haas Quarte t 2 # Gramophone Award, 2007 # BBC Music Magazine Award, 2007 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2006 # Supersonic Award of Pizzicato, 2006 SU 3877-2 # BBC Music Magazine Chamber Choice, 2008 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2007 # Gramophone Editor’s Choice, 2008 # Cannes Classical Award, MIDEM 2009 SU 3922-2 # Gramophone Disc of the Month, 2010 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2010 # Caecilia, 2010 # Diapason d’Or de l’Année, 2010 # Choc de Classica, 2011 SU 3957-2 # Gramophone Award, Recording of the Year, 2011 # BBC Music Magazine Disc of the Month, 2010 # Sunday Times Album of the Week, 2010 # ClassicsToday Disc of the Month, 2011 SU 4038-2/1 # Gramophone Award, 2014 SU 4110-2 # Gramophone Award, 2015 # BBC Music Magazine Award, 2016 # Presto Classical Recordings of the Year, 2016 # Sinfini Best Chamber Album of the Year, 2015 # BBC Radio 3 Disc of the Week, 2015 # MusicWeb International Recording of the Month, 2015 SU 4172-2/1 SU 3877-2 SU 3922-2 SU 3957-2 SU 4038-2/1 # Gramophone Award, 2018 # Presto Classical Recordings of the Year, 2017 # Gramophone Editor’s Choice, 2017 # BBC Music Magazine Disc of the Month, 2017 # Sunday Times Album of the Week, 2017 # Diapason d’Or, 2018 SU 4195-2/1 # Presto Classical Recording of the Week, 2019 # Europadisc Disc of the Week, 2019 # The Times 100 Best Records of the Year, 2019 SU 4110-2 SU 4172-2/1 SU 4195-2/1 SU 4271-2 SU 4271-2 tomáš NetoPil co ndu ctor 3 You hear everything and yet not a single note obtrudes. -

000000015 1.Pdf

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE CLOSING OF MARTINŮ REVISITED ’ HUMOUR IN MARTINŮ S MUSIC JANUARY—APRIL 2011 VOL.XI NO.1 HISTORIC LPs AUTOGRAPHS IN THE MÉDIATHÈQUE MUSICALE MAHLER NEW PUBLICATIONS & CDs NEW CD MARTINŮ. THE 6 SYMPHONIES contents Recorded Live 3 highlights / events BBC Symphony Orchestra, Jiří Bělohlávek (Conductor) 4 incircle news Onyx Classics, ONYX4061 3CD (due for release in June 2011) 6 news International Martinů Circle Founding Members Closing Concert of the Martinů PEEPH●●LE Revisited Project 8 Martinů Revisited 2009–2010 INTO THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŲ CENTER IN POLIČKA ALEŠ BŘEZINA 10 Historic Recordings for the Library of the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation ZOJA SEYČKOVÁ 11 special series List of Martinů’s Works XI 12 festivals Martinů as a Source of Inspiration CHRISTINE FIVIAN & CECILE PIERBURG 14 research Humour in Martinů’s Music from the 1920s EVA VELICKÁ MARTINŮ OWNED a Kopecký & Co. piano that he kept at his music school in today’s Masary kova Street in Polička and on which he wrote a number of compositions. We do not know exactly 17 research when and from whom he bought the instrument, yet from 1919 he endeavoured to sell it. New Martinů Autographs in Paris When in 1932 the piano was bought by his friend, the Polička-based builder Bohuslav Šmíd, ALEŠ BŘEZINA Martinů expressed his gratitude by writing several minor piano pieces for his children bearing the dedication “To Božánek and Sonička Šmíd“. Martinů was delighted that the piano was in good hands, as is evident from the letter he wrote to Šmíd in Paris on 16 May 1932: 18 events / news “You understand that I parted with it with regret, since it is a friend that collaborated with me on my things, and it cost me a lot of effort to acquire it – I had to write a good few notes to pay for it. -

Classical Music Review in Supraphon Recordings RADEK BABORÁK JAN MARTINÍK & DAVID MAREČEK DVOŘÁK PIANO QUARTET DAGMAR P

VIVACEVIVACEClassicalRevue o klasické Music Reviewhudbû v nahrávkách AUTUMN/WINTERPODZIM / ZIMA 2018 2016 invydavatelství Supraphon Supraphon Recordings Photo © Czech Philharmonic archive Photo © Czech Jirásek Photo © Václav Foto archi PFS archi Foto Foto © Foto Jan Houda LUKÁŠJIŘÍ BĚLOHLÁVEKVASILEK SIMONAJAN MARTINÍKŠATUROVÁ & DAVIDTOMÁŠ MAREČEKNETOPIL © Borggreve Foto Marco IVO Photo © Petra Hajská Photo © Petra Photo © Dušan Martinček Foto © Foto David Konečný Foto © Foto Petr Kurečka MARKODVOŘÁKIVANOVIĆ PIANO QUARTETRADEK BABORÁK ŠTEFANKAHÁNEKMARGITA © Foto Martin Kubica RADEK DAGMAR Photo © Martin Kubica Kurečka Photo © Petr Foto archiv ČF archiv Foto Foto © Foto Martin Kubica BABORÁK PECKOVÁ RICHARD NOVÁK 1 VIVACE AUTUMN/WINTER 2018 Dear friends, orchestra, as well as with the numerous young Czech musicians I am writing the introductory lines of the new Vivace issue well into whom he, at the right moment, munificently aided on their journey the Advent time. Although I could give a thorough account of all the to “the world”. When I now view our autumn recordings, this virtu- albums Supraphon released in the autumn, my mind keeps returning ally applies to all the artists featured on them: Jan Martiník (Schu- to one of them in particular – and above all the man whose name it bert – Winterreise), Radek Baborák (Mozart), Ivo Kahánek and Jan bears – Jiří Bělohlávek. His recording of Bohuslav Martinů’s opera-pas- Fišer (Kalabis), Dagmar Pecková (Nativitas)... That is the answer to toral What Men Live By, with the Czech Philharmonic, was released the unasked question as to what legacy Jiří Bělohlávek left behind this October. Jiří Bělohlávek made it in world premiere four years ago, and what he lived by. -

YO-YO MA Le Tour Du Monde En 36 Concerts

Clic Musique ! CLICMAG N° 84 Votre disquaire classique, jazz, world JUILLET/AOÛT 2020 ClicMag YO-YO MA Le tour du monde en 36 concerts © Marco© Steven Borggreve Devine Retrouvez les 25 000 références de notre catalogue sur www.clicmusique.com ! Sélection Supraphon Twelfth night recital, Prague 1987 J.S. Bach : Les Concertos Brande- J.A. Benda : Sonates, sonatines et Pavel Sporcl & his Gipsy Way Concertos de Brahms, Schumann, A. Dvorák : Cypress; Evening Songs; Ivan Moravec, piano bourgeois mélodies Ensemble : Gipsy Fire Bloch, Prokofiev, Martinu, Ibert, Gypsy Songs G. Leonhardt; E. Melkus; N. Harnoncourt; I. Bilej Broukova; E. Keglerova; H. Pavel Šporcl, violon; Ensemble Gipsy Way Lalo... Pavol Breslik, ténor; Robert Pechanec, Wiener Konzerthaus; J. Mertin Zemanova; H. Flekova; M. Stryncl André Navarra; Suk; Ancerl; Silvestri piano SU4190 - 2 CD Supraphon SU4213 - 2 CD Supraphon SU4184 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4180 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4229 - 5 CD Supraphon SU4215 - 1 CD Supraphon A. Dvorák : Quatuor pour piano n° A. Dvorák : Intégrale des duos A. Dvorák : Quatuors pour piano Gried, Ravel, Prokofiev : Concertos L. Janácek : Messe glagolitique; L. Janácek : Suites orchestrales 2, op. 87 / J. Suk : Quatuor pour Moraves n° 1 et 2 pour piano L'Évangile éternel Orchestre Symphonique de la radio de piano, op. 1 Simona Saturová; Markéta Cukrová; Petr Dvorák Piano Quartet Ivan Moravec, piano; Czech Philharmonic; Chœur Philhamonique de Prague; OS de Prague; Tomáš Netopil Quatuor Suk Nekoranec; Vojtech Spurny Karel Ancerl la radio de Prague; Tomas Netopil SU4227 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4238 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4257 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4245 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4150 - 1 CD Supraphon SU4194 - 1 CD Supraphon Frantisek Jiranek : Concertos pour V. -

Mirandolina-Text-1385715627.Pdf

Rok české hudby 2014 V posledních letech jsme svědky až nepřehledného množství „roků“ a „dnů“ zasvěcených různým tématům, většinou z iniciativy nadná- rodních administrativ. Rok české hudby je ovšem záležitostí tradiční a přirozeně i v zahraničí očekávanou s kořeny v r. 1924, kdy se poprvé slavilo kulaté výročí národního skladatele B. Smetany (1824–1884) a zároveň proběhl mj. i festival soudobé hudby s komorní hudbou L. Janáčka (* 1854). Jsou to roky zakončené čtyřkou, protože do těchto let spadá výročí zhruba stovky významných hudebních umělců u nás – B. Smetany, A. Dvořáka, L. Janáčka, J. Suka, E. F. Buriana, folkloristy F. Sušila, ale také např. K. Kryla a E. Olmerové a řady dalších. V r. 2014 uplyne kulatých sto let od narození dirigenta a skladatele R. Kubelíka, jehož jméno je spjato s různými milníky historie České filharmonie, nebo klavíristy a skladatele J. Páleníčka, výrazného interpreta klavírního díla Janáčka a Martinů. Z osobností spjatých s operou vzpomeňme pří- telkyni G. Verdiho sopranistku T. Stolzovou (+ 1834), sopranistku Metropolitní opery J. Novotnou (+ 1994), vynikající Rusalku a Ma- řenku M. Šubrtovou (* 1924). Šedesát let uplyne také od založení Janáčkovy filharmonie Ostrava. Rok české hudby 2014 se poprvé odehrává pod patronací umělec- kého páru s vynikající mezinárodní prestiží – mezzosopranistky M. Kožené a šéfdirigenta Berlínské filharmonie Sira S. Rattla. Je otevřeným projektem, do kterého se hlásí pořadatelé profesionální i neprofesionální kultury všech žánrů a formátů se svými projekty. Všechna tato mnohost je spjata logem Roku české hudby. Se zvláštní nabídkou se setkáte také na ČT ART a na Vltavě Českého rozhlasu. K programu přispějí významně ostravští pořadatelé, zejména Colours of Ostrava, MHF Janáčkův máj, Janáčkova filharmonie Ostrava, Ostravské centrum nové hudby a Národní divadlo moravskoslezské, které se navíc pražským provedením své inscenace Mirandolina 7. -

BOHUSLAVMARTINU the International Martinů Circle

BOHUSLAV MARTINU ° The Bohuslav Martinů Foundation The Bohuslav Martinů Institute The International Martinů Circle Opera Performances MAY—AUGUST Martinů’s 2007 Correspondence with / VOL. VII Zdeněk Zouhar / NO. Martinů & Sport 2 NEWS & EVENTS NEW BOOKS NEW CDs ts– Conten VOL. VII / NO.2 MAY—AUGUST 2007 e WelcomE —NEWS FROM POLIČKA —HISTORICAL RECORDING —THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ DAYS —NEW CONTRACT —INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE r Operas JULIETTE IN GÖRLITZ • PETR VEBER, GÜNTER THIELE t Operas / News THE MARRIAGE • EVA VELICKÁ —MARTINŮ ENSEMBLE FROM SPAIN y ConcertS / News —MARTINŮ FEST IN POLIČKA • LUCIE BERNÁ —BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ PIANO QUINTETS u ConcertS / News A CONCERT BY THE APOSIOPÉE ENSEMBLE • GUY ERISMANN —FORTHCOMING CD h Interview WITH… JIŘÍ KOLLERT i Letters • EVA VELICKÁ DEAR FRIEND ZOUHAR: BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S LETTERS TO ZDENĚK ZOUHAR 1949–1959 j NewBooK • VÍT ZOUHAR MILOŠ ŠAFRÁNEK: ENCOUNTER AFTER FIFTY YEARS s News • ALEŠ BŘEZINA MARTINŮ REVISITED 2009 BUDAPEST SPRING FESTIVAL l Events / News • MARTINA FIALKOVÁ d ResearcH 2) New CDs &Books A ‘SPORTSMAN COMPOSER’? MARTINŮ, SPORT & SOKOL y • ANTHONY BATEMAN Bohuslav Martinů in Alassio, Italy 1952 © PBM me– b Welco THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ NEWS FROM POLIČKA INTERNATIONAL NEWSLETTER is published by the ON SATURDAY 14 April the traditional Bohuslav Martinů Foundation in collaboration MARTINŮ CIRCLE spring exhibition dedicated to Bohuslav with the Bohuslav Martinů Institute in Prague Martinů was opened in the Municipal Members receive the illustrated Bohuslav EDITORS Museum and Gallery in Polička.