Into the Woods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Action of God's Love

Christ Episcopal Church, Valdosta “The Action of God’s Love” (2 Corinthians 4:14-5:1) June 6, 2021 Dave Johnson In the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Apostle Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians is far and away his most vulnerable letter. He does not water down the realities of his suffering as an apostle of the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ—as he writes: Five times I have received the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked. And besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches. Who is weal, and I am not weak? (2 Corinthians 11:24-29). Not only did Paul suffer all these things in his apostolic ministry, he also suffered in his personal life, especially with what he dubbed his “thorn in the flesh”: “Therefore, to keep me from being too elated, a thorn was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan to torment me, to keep me from being too elated.” Paul does not reveal what this specific “thorn in the flesh” was, though there are many theories about it, but he does reveal what he did about it: “Three times I appealed to the Lord about this, that it would leave me, but he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness’” (2 Corinthians 12:7-9). -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

Book Files/0763670618.Chp.2.Pdf

Into the Grey CelIne KIernan INTOGREY_70610_HI_US.indd 3 4/22/14 1:26 PM 1. nan Burns the House Down e were watching telly the night Nan burnt the house W down. It was March 1974, and I was fifteen years of age. I thought I lost everything in that fire, but what did I know about loss? Nothing, that’s what. I would learn soon enough. I think the fire changed us — me and Dom. Though I didn’t feel much different at first, I think something inside of us opened up, or woke up. I think, all at once, we began to understand how easily things are broken and taken and lost. It was like walking through a door: on one side was the warm, cosy sitting room of our childhood; on the other, a burnt-out shell of ash and char. I think that’s how the goblin-boy was able to see us. Though he’d been there for every summer of our child- hood — mine and Dom’s — we’d only been stupid boys until then. Stupid, happy, ignorant boys. And what in hell would he have had in common with two stupid boys? But after the fire we were different. We were maybe a little bit like him. And so he saw us, at last, and he thought he’d found a home. * * * INTOGREY_70610_HI_US.indd 1 4/22/14 1:26 PM The night of the fire, Ma had brought chips home and we were eating them from the bags, our feet on the coffee table, our eyes glued to the TV. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

Fungous Diseases of the Cultivated Cranberry

:; ~lll~ I"II~ :: w 2.2 "" 1.0 ~ IW. :III. w 1.1 :Z.. :: - I ""'1.25 111111.4 IIIIII.~ 111111.25 111111.4 111111.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NArIONAl BUR[AU or STANO~RD5·J96:'.A NATiDNAL BUREAU or STANDARDS·1963.A , I ~==~~~~=~==~~= Tl!ClP'llC....L BULLl!nN No. 258 ~ OCTOBER., 1931 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WASHINGTON, D_ C. FUNGOUS DISEASES OF THE CULTIVATED CRANBERRY By C. L. SHEAll, PrincipuJ PatholOgist in. Oharge, NELL E. STEVESS, Senior Path· olOf/i8t, Dwi8ion of MycoloYlI una Disruse [{ul-vey, and HENRY F. BAIN, Senior Putholoyist, DivisiOn. of Hortil'Ulturul. Crops ana Disea8e8, Bureau of Plant InifU8try CONTENTS Page Page 1..( Introduction _____________________ 1 PhYlllology of the rot fungl-('ontd. 'rtL~onomy ____ -' _______________ ,....~,_ 2 Cllmates of different cranberry Important rot fungL__________ 2 s('ctions in relation to abun dun~e of various fungL______ 3:; Fungi canslng diseuses of cr':ll- Relatlnn betwpen growing-~eason berry vlnrs_________________ Il weather nnd k('eplng quality of Cranberry tungl o.f minor impol'- tuncB______________________ 13 chusettsthl;' cranberry ___________________ ('rop ill :lfassa 38 Physiology of tbe T.ot fungl_____ . 24 Fungous diseuses of tIle cl'llobpl'ry Time ot infectlou _____________ 24 and their controL___ __________ 40 Vine dlseas..s_________________ 40 DlssemInntion by watl'r________ 25 Cranberry fruit rots ___________ 43 Acidity .relatlouB_____________ _ 2" ~ummary ________________________ 51 Temperature relationS _________ -

Transcript of Oral History Interview with Steve Glasper

Oral history interviews of the Vietnam Era Oral History Project Copyright Notice: © 2019 Minnesota Historical Society Researchers are liable for any infringement. For more information, visit www.mnhs.org/copyright. Version 3 August 20, 2018 Steve Glasper Narrator Douglas Bekke Interviewer April 9, 2018 Fridley, Minnesota Steven Glasper -SG Douglas Bekke -DG DB: Minnesota Historical Society Vietnam Oral History Project interview with Steve Glasper in his home in Fridley, Minnesota on 9 April 2018. Mr. Glasper can you please say and spell your name? SG: Yes my name is Steve Glasper. S-T-E-V-E G-L-A-S-P as in people-E-R DB: And your birth date? SG: 10-31-49 DB: And your place of birth? SG: St. Joseph, Missouri. DB: What do you know about your ancestry? SG: Well, being African-American, sometimes it’s a little difficult, gets a little hazy when you start thinking about how far back you go. I can go back—fortunately for me we’ve had a pretty good, family make up and we’ve always kept in touch with. I can go back as far as my great- great-grandparents at least having some knowledge, and my great-great-grandmother I actually knew Mildred Webster because she was still alive. She died, she was 106 when she passed. DB: That’s pretty amazing. SG: Yeah. We had the opportunity to actually learn some things from her even though I was a small child, but my father is from St. Joseph, Missouri, my mother is from St. Joseph, Missouri. -

November 2013 School Server Crashes, of Hard Knocks All Data Lost Concussion Dan- Principal Says Low Budget, Gers Haunt High High Turnover and Old Age School Football

The Poly Optimist John H. Francis Polytechnic High School Vol. XCIX, No. 4 Serving the Poly Community Since 1913 November 2013 School Server Crashes, of Hard Knocks All Data Lost Concussion dan- Principal says low budget, gers haunt high high turnover and old age school football. responsible for tech failure. By Danny Lopez By Yenifer Rodriguez of recovering the files, including Staff Writer Editor in Chief outsourcing. “There are companies that specialize in recovering data from High school football players Several Poly faculty members damaged or corrupted hard drives,” are nearly twice as likely to sustain lost years of data when a local stor- Schwagle said. “So I’m going to a concussion as college players, age drive, known as the “H” drive, according to a recent study by the failed two weeks ago. [ See Server, pg 6 ] Institute of Medicine. “We have no error codes, no Because a young athlete’s brain symptoms, nothing to tell us what is still developing, the effects of a went wrong,” said ROP teacher and Photo by Lirio Alberto concussion, or even many smaller computer expert Javier Rios. Giving Back hits over a season, can be far more SHOWTIME: Parrot freshman Priscilla Castaneda danced for the Clippers. The device was ten years old, ac- Two Parrots who got detrimental to a high school player cording to Rios. No back up system compared to head injury in a college was in place. help themselves are try- player. Poly Frosh Dances at “A lot of turnover in the technol- ing to return the favor. The study estimated that high ogy office and budgets cuts of 20% school football players suffered 11.2 school wide in the last few years By Christine Maralit concussions for every 10,000 games Staples Half-time Show have affected our ability to man- Staff Writer and practices. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

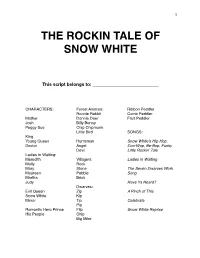

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Das Genie, Das Ich Nicht Vermarkten Wollte

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Tandem Das ungleiche Paar Paul Simon und Art Garfunkel werden 75 Von Christiane Rebmann Sendung: 04.11.2016 um 19.20 Uhr Redaktion: Bettina Stender Sprecher: Peter Binder Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Tandem können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de oder als Podcast nachhören: http://www1.swr.de/podcast/xml/swr2/tandem.xml Mitschnitte aller Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Tandem sind auf CD erhältlich beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden zum Preis von 12,50 Euro. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Bestellungen per E-Mail: [email protected] Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de 2 O-Ton Das war eine großartige Periode. Die beste. Da waren wir auf der Überholspur. Auch musikalisch war das eine tolle Zeit, weil da eine Menge Energie in der Luft lag. Das war eine Zeit der Experimente. Und das Ganze folgte einer großen Ära des Rock'n'Roll. Die Quellen, aus denen wir Musiker damals schöpfen konnten, waren also sehr reichhaltig. In den folgenden Jahrzehnten konnten wir nie mehr auf so ergiebige Quellen zurückgreifen. Die Musik der 70er Jahre zum Beispiel war viel flacher und nicht annähernd so anregend wie die aus den 50er Jahren.