The Hype Man As Racial Stereotype, Parody, and Ghost in Afro Samurai Treaandrea Russworm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CREDIT Belongs to Anime Studio, Fansubbers, Encoders & Re-Encoders Who Did the All Hard Work!!! NO PROFIT Is Ever Made by Me

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/1vc3 < іѕт!: < AT׀ ↓Αпіме dd Disclaimer: All CREDIT belongs to Anime Studio, Fansubbers, Encoders & Re-Encoders who did the all hard work!!! NO PROFIT is ever made by me. Period! --------------------- Note: Never Re-post/Steal any Links! Please. You must Upload yourself so that My Links won't get Taken Down or DMCA'ed! --------------------- Be sure to Credit Fansub Group, Encoders & Re-Encoders if you know. --------------------- If you do Plan to Upload, be sure to change MKV/MP4 MD5 hash with MD5 Hasher first or Zip/Rar b4 you Upload. To prevent files from being blocked/deleted from everyone's Accounts. --------------------- Do Support Anime Creators by Buying Original Anime DVD/BD if it Sells in your Country. --------------------- Visit > Animezz --------------------- МҒ links are Dead. You can request re-upload. I will try re-upload when i got time. Tusfiles, Filewinds or Sharebeast & Mirror links are alive, maybe. #: [FW] .hack//Sekai no Mukou ni [BD][Subbed] [FW] .hack//Series [DVD][Dual-Audio] [FW] .hack//Versus: The Thanatos Report [BD][Subbed] [2S/SB/Davvas] 009 Re:Cyborg [ВD][ЅυЬЬеd|CRF24] A: [ЅВ] Afro Samurai [ВD|Uпсепѕогеd|dυЬЬеd|CRF24] [МҒ] Air (Whole Series)[DVD][Dual-Audio] [МҒ] Aquarion + OVA [DVD][Dual-Audio] [2Ѕ/ЅВ] Asura [ВD|ЅυЬЬеd|CRF24] B: [МҒ] Baccano! [DVD][Dual-Audio] [МҒ] Basilisk - Kōga Ninpō Chō [DVD][Dual-Audio] [TF] Berserk: The Golden Age Arc - All Chapters [ВD|Uпсепѕοгеd|ЅυЬЬеd|CRF24] [DDLA] Black Lagoon (Complete) [DVD/BD] [МҒ] Black Blood Brothers [DVD][Dual-Audio] [МҒ] Blood: -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

Afro-Orientalism; an Exploration of The

Afro-Orientalism; An Exploration of the Relationship Between African Americans and the Japanese from the 18th to the 21st Century By: Alana Lewis Abstract The study of Afro-Asian relationships, often referred to as Afro-Orientalism, is a subject that is not widely discussed. This relationship is a cultural and often political interaction of two vastly different cultures, that have found a common identity and connectedness between themselves even across oceans. My honors thesis will specifically address the Afro-Asian relationship between African Americans in the United States and Japanese people. The benefit of the previous research that has been done in this study is that it sets the foundation for Afro- Orientalism. Additionally, those who have explored in this area have explicated the specific problems that fester as a manifestation of this Afro-Asian relationship such as the World Color Line. However, it fails address the development of the Afro-Asian relationship from 1902 in comparison to the 21th century. It is important to understand how the dynamics between cultures and their interconnectedness with one another develop with changing cultural ideologies over time. This paper will extend beyond existing scholarship about cultural politics and the critical problem of World Color Line. It will address the relationship in the early 20th to early 21st century to explore how new frame works of cultural understanding has changed the dynamics between the two cultures. To do this I will primarily look at Bill Mullin’s “Afro-Orientalism”, Gerald Home’s “Facing the Rising Sun: African Americans, Japan, and the Rise of Afro-Asian Solidarity”, Tze-Yue G. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

2014: of the Heartland

2 2014: Gem of the Heartland TABLE OF CONTENTS Convention Info.........................4 Cosplay......................................17 Registration...............................5 Program Schedule.....................22 Sponsors...................................6 Panel Descriptions.....................25 Volunteers.................................7 Family Programming..................30 Guests of Honor........................8 Video Gaming............................32 Charity Auction.........................12 Tabletop Gaming.......................33 Attractions.................................12 Video Room Schedule..............35 Amenities..................................13 Show Summaries......................39 Cafe Ai......................................14 Staff & Thanks..........................43 Photoshoot...............................16 Autographs...............................44 HOURS OF OPERATION Convention Hours Registration 8AM FRI- 7PM SUN FRI: 9AM -10PM Opening Ceremonies SAT: 10AM-6PM FRI: 5-6PM SUN: 10AM-4PM Closing Ceremonies Pre-registration for 2015: SUN: 5-6PM SUN: 3PM-6PM Anime Marketplace Cosplay Central FRI: 4PM-8PM FRI: 12PM-10PM SAT: 10AM-6PM SAT: 9AM-3PM SUN: 10AM-4PM SUN: 10AM-2PM **Room opens ½ hour earlier each day for our AnimeIowa Sponsors! Masquerade SAT: 6:30PM-8:30PM Maid Cafe Ai FRI: 12PM-4PM Consweet Sign-up: 8AM - 11AM FRI: 2PM - Con Closing **Session info: see page 14 (While supplies last!) 1 Convention Rules & Info Hotel: 1. Don’t Litter: Trash bins are all around the convention center and hotel. Keep it clean! 2. Signs and Adhesives: Bring your signs and posters to the BRIDGE before you hang them. Tape and adhesives are not to be used on hotel walls, doors, or any other surface. See the INFO DESK for more information. 3. Sleeping in Convention Spaces: Sleeping is not allowed in public spaces (ie: hallways, stairways, elevators, video rooms, tables, restrooms, etc). If you are found doing so, you will be asked to move. If found again, we will ask you to leave the convention. -

Afro Samurai's

AFRO SAMURAI, THE FIRST JAPANESE MANGA TO MAKE ITS ANIME DEBUT IN ENGLISH, IS BREAKING ALL BOUNDARIES. METROPOLIS SPEAKS WITH ITS CREATOR AHEAD OF THE MOVIE VERSION’S TOKYO PREMIERE BY ANDREW LEE CHANCES ARE, YOU KNOW ALL ABOUT SAMUEL L. JACKSON. But it’s just as likely you’ve never seen him as a revenge-seeking, sword- wielding black Samurai with great hair—the Afro Samurai. This cult anime began life as a manga created by Tokyo-based artist Takashi “Bob” Okazaki. Over a couple of beers at his apartment, Okazaki spoke about the influences behind his work, and about befriending the superstar American actor. “I first started sketching Afro when I was a student,” explains the 33-year- old. “That was 11 years ago. At first they were just sketches of black guys because I really like hip-hop and soul, R&B and reggae. I also loved that ’70’s TV show Soul Train, which used to be on NHK. Those guys had really, really big afros,” he says, shaking his own fairly decent mop of hair. From those initial doodles and Okazaki’s love of samurai movies, a story began to unfold around the main character. The result was the manga Afro Samurai, first published in 1998 in a fanzine called Nounou Hou. “At that time, I was really frustrated,” Okazaki says. “I was working as an illustrator and wanted to go crazy with the illustrations. But the clients always asked me not to go over the top. So with my manga I only drew what I liked. -

Newsletter 01/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 01/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 243 - Januar 2009 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 01/09 (Nr. 243) Januar 2009 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, zwischen zwei Double Features (ein Hallo Laser Hotline Team, liebe Filmfreunde! Film vor Mitternacht, der zweite da- aus Eurem letzten Editorial (Newsletter Nr. 242) meine ich herauszuhören ;-) , dass der Herzlich willkommen zur ersten Ausga- nach) oder dem überlangen gewöhnliche Sammler von Filmen, Musik und be unseres Newsletters im Jahre 2009! AUSTRALIA, den Theo fachmännisch was auch immer, irgendwann auf den Down- Allen unseren guten Vorsätzen für das so aufbereitete, dass es kurz vor Mit- load via Internet angewiesen sein wird. Ich neue Jahr zum Trotz leider wieder mit ternacht eine Pause gab. Immerhin fan- denke (hoffe), nein! Ich verstehe alle Be- fürchtungen, dennoch, solange unsere Gene- etwas Verspätung. Alte Gewohnheiten den sich für alle Filmpakete auch Zu- ration lebt, wird es runde Scheiben geben! los zu werden ist eben nicht so einfach. schauer – wenn auch nicht sehr viele. Glaubt mir! Aber es gilt natürlich wie immer unser Doch aller Anfang ist schwer. Hier wird Das Internet ist im Access-Bereich bei der Leitspruch: “Wir arbeiten daran!” Ein sicherlich bei der nächsten Silvester- doppelten Maximalrate von DVD angelangt, dennoch tun sich alle VOD (video on Gutes hat die kleine Verspätung je- Film-Party die Mundpropaganda zu demand)- Dienste extrem schwer. -

1567876883594.Pdf

Intro The story of this land goes a little something like this: wherever strife, and bloodshed exists in this world, you can be 300% sure that these two old pieces of cloth had something to do with it. One of these two headbands distinguishes the wearer as the greatest swordsman, and the God of this world. Some say they even possess power unimaginable by mortals. Point is, they’re untouchable, nobody can ever challenge them, except whoever wears the Number 2 headband. The Number 2 headband bestows only grief and regret. Unlike the Number 1, anyone and everyone can challenge the Number 2, to claim the headband, and the right to challenge God for his throne. Who can say where the superstition ends and the supernatural begins, but for mankind, that’s more than enough to keep the cycle of revenge spinnin’. The latest poor sap to get sucked into this bullshit is the Afro Samurai. Ya’ see, once upon a time, Afro’s pop was the Number 1 swordsman. With young Afro bearing witness, he accepted the Number 2’s request for a duel. His name was Justice, a gangly scarecrow-looking motherfucker with skin like a snow leopard, and way too many spaghetti westerns in his DVR. Thanks to Papa-Afro's need for an audience, and Justice’s sneak attack, that little boy got to see his dad’s severed head dangle in front of him. Afro is a grown-ass man now. His losses didn’t stop at his only real father, his surrogate family got cut to pieces too, all thanks to these damn headbands. -

Afro Slices His Way Back to the Top in Afro Samurai: Resurrection

Afro Slices His Way Back to the Top in Afro Samurai: Resurrection Posted on February 4, 2009 by Rachel Seldom is a sequel ever as good as the original. In Afro Samurai: Resurrection, the movie sequel to the five episode-long series, Afro returns after meting out the pain to his father’s killer. Plot Summary Years after Afro Samurai avenged his father, the deadly warrior has laid down his sword and tries to live a life of peace. But one cannot don the Number One headband and have a tranquil ever after. Those who have lost loved ones under Afro’s skilled blade have come back to exact payment for the pain he’s inflicted, and the price is too high for the silent samurai to meekly pay. Once again Afro must sharpen his sword and slice his way back to the top. This time, it isn’t revenge– it’s personal. Review Afro Samurai: Resurrection is a rare gem in media– it’s a sequel that isn’t just as good as its predecessor, it’s better. Soi and boob-obsessed evil scientist, ©Funimation 2009 The movie is more of an adventure than the slice and dice gore fest of the first series. Afro is back with his sidekick Ninja Ninja to put the hurt on some vengeful ghosts made in Afro’s bloody wake. It’s a solid telling of tables turned and whirlwinds reaped. In its ninety minutes, Resurrection takes us back to the motley world of hip hop and history, rap and rice paddies. Afro comes face to face with those who felt the bitter bite of his vengeance. -

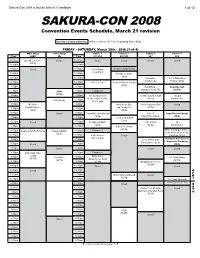

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

![1. .Hack//G.U. Trilogy + Ova Returner [Sub Esp][MEGA] 2. .Hack//Legend of the Twilight 12/12 [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3467/1-hack-g-u-trilogy-ova-returner-sub-esp-mega-2-hack-legend-of-the-twilight-12-12-sub-esp-mega-3-3443467.webp)

1. .Hack//G.U. Trilogy + Ova Returner [Sub Esp][MEGA] 2. .Hack//Legend of the Twilight 12/12 [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 3

1. .Hack//G.U. Trilogy + Ova Returner [Sub Esp][MEGA] 2. .Hack//Legend of the Twilight 12/12 [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 3. .Hack//Liminality 4/4 [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 4. .Hack//Quantum 3/3 [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 5. .Hack//Roots 26/26 [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 6. .Hack//SIGN 26/26 + 3 ovas [Sub Esp][MEGA] 7. .hack//The Movie: Sekai no Mukou ni [Sub Esp][MEGA] 8. 07 Ghost 25/25 [Sub Esp][MEGA] 9. _Summer 2/2 + 2 especiales [Sub Esp][MEGA-ZS] 10. ¡Corre Meros! [Español][MEGA] 11. ¿Quién es el 11º pasajero? 1/1 [Pelicula][Español][Mega] 12. 1001 Nights [Sub Esp][MEGA-SHARED] 13. 11 eyes 12/12 + ova [Sub Esp][MEGA] 14. 12 Reinos 45/45 [Latino][MEGA] 15. 2x2=Shinobuden 12/12 [Sub Esp][MEGA] 16. 30-sai no Hoken Taiiku 12/12 [Sub Español] [MEGA] 17. 3x3 Eyes 4/4 [Dual Audio][MEGA] 18. 3x3 Eyes Seima Densetsu 3/3 [Dual Audio][MEGA] 19. 5 Centimetros por Segundo [Pelicula] [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 20. 8 Man After [Sub Esp][MEGA] 21. A Channel 12/12 + OVAs + Especiales [Sub Esp] [MEGA] 22. A Piece of Phantasmagoria 15/15 [Sub Esp][MEGA] 23. A.D. Police 12/12 +3 ovas [Sub Esp][MEGA] 24. Aa Megami-Sama OVAS Sub Esp[MEGA-MF] 25. Aa Megami-sama Sorezore No Tsubasa 24/24 [Sub Esp][MEGA-MF] 26. Aa! Megami-sama 26/26 [Sub Esp][MEGA] 27. Aa! Megami-sama [PELICULA][MEGA-MF] 28. Abarenbou Kishi!! Matsutarou 23/23[Sub-Esp][Mega] 29. Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai 13/13 [Sub Esp][MEGA] 30.