A Guide to Suitable Bass Solo Vocal Repertoire by J. S. Bach For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

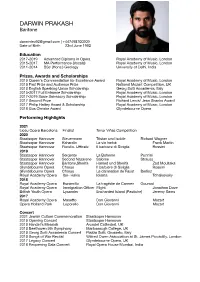

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, L. C.(2019). Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5248 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher by Lara C. Wilson Bachelor of Music Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 1991 Master of Music Indiana University, 1997 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: E. Jacob Will, Major Professor J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Lynn Kompass, Committee Member Janet Hopkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Lara C. Wilson, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my family, David, Dawn and Lennon Hunt, who have given their constant support and unconditional love. To my Mom, Frances Wilson, who has encouraged me through this challenge, among many, always believing in me. Lastly and most importantly, to my husband Andy Hunt, my greatest fan, who believes in me more sometimes than I believe in myself and whose backing has been unwavering. -

Fall 2012 Volume 39, No

ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE AMERICAN CHORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION Fall 2012 Volume 39, No. 1 PODIUM techniques, ideas, song titles....IL- President’s Message ILLINOIS ACDA EXECUTIVE BOARD ACDA works well not just because of our guest clinicians, but because we have so many generous experts President in our own organization who are Beth Best HOT TIME IN THE OLD TOWN! willing to share with the rest of us. Hill Middle School [email protected] Thank you to all who attended and Dr. Karyl Carlson is putting the Past President helped with the Summer ReTreat 2013 Re-treat together, and has some exciting headliners and ses- Brett Goad in June! It was definitely a "hot time" in more ways than one! Our sions planned! Watch for her arti- Hinsdale South High School—retired director's chorus guest conductor, cles in the winter and spring issues [email protected] Dr. Josh Habermann, gave us a lot of The Podium. Also, please read President-Elect to think about in preparing and ex- Karyl Carlson pressing the varied music he chose Continued on page 2 Illinois State University for us. He was a joy to work with. Laura Farnell shared many of her [email protected] ideas for working with younger In this issue Treasurer voices. A highlight of her sessions Leslie Manfredo was the work she did with Deb President’s Message p. 1 Save the Date—ReTreat 2012 p. 2 Illinois State University Aurelius-Muir's boys, and practical Commissioning New Music p. 3 Just thinking...Why we do what p. 8 [email protected] tips for teaching the changing voice. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon.