3 the Reuse of Buildings: Libraries Behaving Sustainably 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2015 E-Newsletter

Winter 2015 E-newsletter Dear Reader, Welcome to the winter edition of our e- newsletter. The newsletter covers news from Cornwall Record Office and the Cornish Studies Library and is sent out quarterly. If you know anyone who would like to subscribe, please ask them to send a blank email to [email protected] with ‘Subscribe to E- newsletter’ in the subject line. We hope you enjoy this edition, and have a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. We look forward to seeing you in 2016. Kind regards, The Archives and Cornish Studies Team News Christmas Open Hours Please note, the Cornish Studies Library will be closed from Wednesday December 23rd and reopens on Monday January 4th. Cornwall Record Office closes at 1pm on Thursday December 24th and will reopen on Tuesday January 5th. Kresen Kernow Project The project to build Cornwall’s new archive centre has officially launched and the delivery phase has commenced. Archive Services Manager, Deborah Tritton, will be taking on the role of Project Director for the duration of the Kresen Kernow build. Her post will be filled by Sally Weston, who joins us from the BBC Archives. Kresen Kernow Staff Site Visit Earlier this month members of staff visited the Kresen Kernow site to see the work that has already been carried out to build a public walkway through the site. Although 80% of the work has been underneath the surface, it was lovely to see the area beginning to take shape, and to admire design elements such as statues and a water feature made from beer bottles. -

Opportunity for Artists Kresen Kernow Public Art Project

Information Classification: CONTROLLED Opportunity for artists Kresen Kernow public art project Summary Cornwall Council is commissioning a new public artwork for Kresen Kernow, Cornwall’s new archive centre, in Redruth. Funded by Arts Council England, the artwork will be inspired by the theme My Cornwall: My Home and will commemorate the temporary return to Cornwall of several historic Cornish manuscripts in 2021. The commission will run from May 2021 and will be unveiled to the public on St Piran’s Day (5 March) 2022. The artwork could be situated indoors at Kresen Kernow or outdoors (see Appendix 1 for photos of potential locations). The chosen artist will work with community groups and the Archives and Cornish Studies Service (ACSS) team to inspire the high-quality artwork which will encourage interaction and engagement, and will draw people to Kresen Kernow and Redruth. The work may be permanent or temporary, but we will be looking for ideas that make a lasting impression of some kind and which represent good value for money. Please read the New Rules of Public Art (Appendix 2) which will give you an idea of the way we are thinking about this commission. £35,000 is available for this commission The procurement of the artist will take place over two stages: Stage 1 - an open call for Expressions of Interest (EOI) in response to the themes. No concept designs or specific ideas need to be submitted at Stage 1. A panel will shortlist from these EOIs. Stage 2 - up to five artists will be invited to tender at Stage 2, with a concept design and quotation. -

Why Is This Such a Special Exhibition? There Has Long

Information Classification: PUBLIC Out of the Ordinary / Mes a’n Kemmyn Frequently Asked Questions Why is this such a special exhibition? There has long been the desire to display these treasured manuscripts back in Cornwall, but there hasn’t been a suitable gallery space. A key aspiration of the Kresen Kernow project (funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Cornwall Council) was to build a gallery space capable of displaying loans from national institutions. We are delighted that our Treasures Gallery meets all the specific security and environmental requirements. The exhibition has been funded through the National Lottery Heritage Fund grant. What are the manuscripts? The four manuscripts are listed below. They are all fully digitised and available to view online at these links: The Cornish Ordinalia: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/e0e7b827-9273-45a8-87ce-7e9f095dfa0c/ Creation of the World: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/7ef86de0-65c3-43d2-9431-322e40a0accd/ The Life of St Meriadoc (Bewnans Meriasek): https://www.library.wales/discover/digital- gallery/manuscripts/the-middle-ages/beunans-meriasek/#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=- 1020%2C0%2C6090%2C4247 The Life of St Kea (Bewnans Ke): https://www.library.wales/discover/digital-gallery/manuscripts/early- modern-period/beunans-ke/#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-885%2C-1%2C5849%2C4080 Why are the manuscripts not held at Kresen Kernow? The manuscripts all found their way into other libraries before detailed records were kept. The Cornish Ordinalia (which dates from around 1400) was given to the Bodleian Library by James Button in 1615. It is unknown where it was for the previous two hundred years. -

November 2019

1 FROM YOUR OWN CORRESPONDENTS AN UPDATE FROM CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY’S AREA REPRESENTATIVES Any opinions or errors in these articles are those of the authors and must not be assumed to be those of Cornwall Archaeological Society. NOVEMBER 2019 Issue 36 THIS MONTH’S FEATURES GWITHIAN SURPRISE! ROW IN THE FAR EAST AQUEDUCT INVESTIGATIONS HELP SAVE THIS HISTORIC BOUNDARY MARKER ALL’S WELL IN BODMIN GWITHIAN SURPRISE! We begin this month with explosive revelations from Adrian Rodda. The explosives works at Upton Towans, which operated from 1889 to 1920, has been scheduled. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1463206 . Few visitors walking the coast path between Gwithian and Hayle across the dunes realise that they are not in a natural landscape. The sand dunes had been shaped and piled to accommodate storage houses for dynamite, gun cotton or nitro-glycerine. People who walk away or parallel to the coast path discover level paths, sometimes with traces of cinders on them. These were the tram tracks laid to connect the store houses with the factory further inland. Just follow the tracks to discover the isolated magazines and remains of the nitric acid works and the sulphuric acid factory. It is difficult to imagine now that dangerous acids were carried by gravity down overhead launders to mix together to make dynamite. The sticks were made of a special clay soaked in the explosive mixture and cut and wrapped by women working in threes in houses which had been surrounded by high sand piles so that if there were an explosion the force would go upwards. -

Kresen Kernow Web Accessibility Statement Using the Kresen

Information Classification: CONTROLLED Kresen Kernow Web Accessibility Statement Using the Kresen Kernow website This website is run by the Archives and Cornish Studies Service of Cornwall Council, based at Kresen Kernow. We want as many people as possible to be able to use the site and have worked to make the site suitable for everyone. We have run regular access checks throughout development, carried out access user testing with visually impaired, blind screen magnifier and screen-reader technology users, and have written html for WCAAGAA standards. In this section we outline some of the access features that are on the site, how to contact us to make suggestions for improving accessibility, and how you can get content in alternative formats if something is not accessible to you. On this website you should be able to: • adjust some of the visual settings of the website, changing colours, contrast levels and fonts (using the short-cuts in the web accessibility section, where you can choose between different colour contrast options and different text sizes) • zoom in up to 300% without the text spilling off the screen • navigate most of the website using just a keyboard • navigate most of the website using speech recognition software • listen to most of the website using a screen reader (including the most recent versions of JAWS, NVDA and VoiceOver) • change the size of the browser window but still read the text - as it will reflow in a single column There are other access changes that you can make depending on how you prefer to access -

Tintagel Parish Council

TINTAGEL PARISH COUNCIL ‘Tintagel’s Great Seal’ Clerk. Mrs S.J. Moth Lincoln House, Phone: 01840 770022 Treven, E-mail : [email protected] Tintagel, Website: www.tintagelparishcouncil.gov.uk Cornwall. PL340DT 3rd April 2014 DRAFT Minutes of the Meeting of Tintagel Parish Council held on Wednesday 2ND April 2014 Present: Cllrs. Wickett, Flower, Roberts, Hockerday, Spurdens, Dyer, Dorman & Lewis Apologies: Cllrs Hodge, Brooks & Goward No members of the public were present Declarations of Interest PA14/01869 – Cllr. Roberts, applicant is fellow Rotarian PA14/1920 – Cllr. Dorman, applicant is a family friend PA14/1407 – Cllr. Wickett, applicant is a relative Tintagel Parochial Church Council – Cllr. Wickett – sits on Trewarmett Methodist Cemetery Committee. Invitation to members of the public to speak prior to meeting regarding items on the Agenda (10 minutes allowed for this item) No members of the public were present. AGENDA Minutes of the previous meeting 5th March 2014 and Matters Arising Page 1429 – The Clerk advised that she had met with Ffion Stanton of CRCC who had given some useful advice. Clerk has further enquiries to make regarding a suitable status for the Visitor Centre. Cllr. Lewis will try and get some advice as she has sat on a Charity board before. It was proposed by Cllr. Spurdens, seconded by Cllr. Hockerday and RESOLVED that the Minutes be signed as a true record of the meeting. All in favour. Minutes 0244 Page No. 1431 REPORTS CCC C/Cllr. Brown reported that the seats at the bottom of Back Lane were damaged. Clerk advised that the handyman had mentioned this to her. -

Buildings at Risk May 2021 Newsletter No.7

Buildings at Risk May 2021 Newsletter No.7 A three-year project led by the Cornish Buildings Group and supported by Historic England and the Cornwall Heritage Trust commenced in September 2020. The funding supports a case officer in order to help identify and monitor buildings at risk and seek solutions for neglected, redundant or derelict listed buildings and unlisted buildings. In the news We have had a successful month in the media. The plight of St Paul’s church, Truro, was picked up by Radio Cornwall which resulted in two radio interviews, one about St Paul’s itself and another on the wider buildings at risk project. We are grateful to Barry West for promoting St Paul’s which set the e-petition rolling again. As I write we have nearly reached 2,600 signatures. This has come to the attention of the Victorian Society who will discuss the case at its next buildings committee. Although the future of this church is still very much in doubt a solution could still be found. Furthermore, our blog post on Melador Farmhouse was used as a feature on the Cornwall Live website. The project was featured in a published article in Old Cornwall/ Kernow Goth, the Journal of the Old Cornwall Society, volume 15, No.1, Spring 2021. Our latest blog posts Focus on Penzance and Kresen Kernow: The Sweet Taste of Success have received good visitor traffic. We are grateful to the Association for Cornish Heritage for hosting our newsletters on their website. Casework Pomery’s Garage, St Mawes We featured this building in Newsletter No. -

Kresen Kernow Guide to Sources Related to Africa

Information Classification: PUBLIC Kresen Kernow guide to sources related to Africa This guide is part of a project to identify key collections and items in our collections relating to Black histories and Cornwall’s links to the British Empire and colonialism. This is a significant piece of work, designed to make it easier to find items and to reveal previously hidden histories. The project will be wide ranging, and has already considered what our collections reveal about Cornish connections to the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Caribbean (find out more here: https://kresenkernow.org/our- collections/collections-guides/black-histories/). This guide highlights sources relating to Cornwall’s interactions with Africa. This document is designed to be an introduction to the types of sources we hold which may be of use in your research. It is not a comprehensive list. We strongly recommend searching our catalogues using the key terms below in order to discover the full range of documents. Key search terms: Africa, individual place/people/event names, Black history, Barbary pirates, missionaries, colonial, colonialism Records tagged with these terms are those with the greatest relevance to the history of these places and themes. We have also included key published sources in this introductory guide. Please note: We recognise that our catalogue contains some terms which are offensive, and some whose meaning has changed over time. Such terms exist within some original records and have been retained to inform users of the nature and content of the sources concerned. They do not reflect the views of the Archives and Cornish Studies Service. -

November 2019 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER November 2019 Our Place on the Internet www.calh.co.uk Email us on [email protected] AGM & Spring Conference Letter from the Chair March 7 – 9, 2020 Firstly I must thank Marion Stephens-Cockroft ‘Clothing in Cornwall: for agreeing to take over as editor of the Vanity & Utility.’ newsletter. Marion grew up in Pelynt parish where her parents farmed. Some of you will Presentations & Speakers remember her mother, Thelma Stephens, a Saturday long time member of CALH. We visited their Through the Middle Ages to the Reformation in farm at Trelay on several occasions and it was Cornwall. - Dr Joanna Mattingly on our last visit, back in 2004, that CALH quote from “The fashion in new fangledness” (a member Colin Squires discovered the remains Richard Carew) – Christine Edwards of a four-holed cross built into the garden wall of the old (now disused) farmhouse. What Demonstration of Hatmaking & Mediaeval Costumes - Katrina Wood remained of the pre-conquest preaching cross was restored and is now displayed within The Development of Military Uniform Pelynt Church. I have known Marion since she in Cornwall - Nick Kelly was a young girl, indeed, back in the 1960's she was one of my first customers when I opened Costumes in Lewis Harding’s my riding school at Trelawne. She has lived in photographs - Jeremy Rowett-Johns Canada for many years but we have always Sunday kept in touch and, after her mother's death a A newly restored archive film of Croggon’s few years ago, she joined CALH on behalf of the Tannery - Grampound Heritage Centre. -

2014-04-Agenda

LUDGVAN PARISH COUNCIL Monthly Parish Council Meeting – Wednesday 9th April 2014 Agenda Public Participation Period. Formal opening of the meeting. 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of the Monthly Parish Council Meeting on Wednesday 12th March 2014 3. Declarations of interest in Items on the Agenda 4. Dispensations 5. Cornwall Council – Planning Applications - For decision; (a) PA14/01819 - Cornwall Farmers Ltd Ludgvan Penzance Cornwall TR20 8AA - siting of a directional sign (b) PA14/02427 - Lower Menwidden Cottage Ludgvan Penzance TR20 8BN - Proposed two storey extension - Mr And Mrs Alexander Hutchison (c) PA14/01626 - Ludgvan House Lower Quarter Ludgvan Penzance Cornwall TR20 8EG - Outline Planning Application with all matters reserved: Proposed new dwelling in existing car park, REVISED PLANS - Mr Andrew Perkin (d) PA14/02644 - The Meadow Back Lane Crowlas Penzance TR20 8EP - Construction of Detached Dwelling - Mr And Mrs Cornish (e) PA14/02676 - Rosevidney Manor Crowlas Penzance TR20 9BX - Replacement of existing painted timber windows - Mr K. Whitam (f) PA14/02677 - Rosevidney Manor Crowlas Penzance TR20 9BX - Listed Building Consent for replacement of existing painted timber windows - Mr K. Whitam 6. Police Matters Crime Report March 2014 7. Comments from Cornwall Councillor - Mr Roy Mann 8. Chairman's Report (a) Extension of broadband to Nancledra area - public meeting held 1st April 9. Footpath Officers Report 10. Clerk’s Report (a) Quarry Meeting - 21st March 2014 (b) Water Activity Concessions - Long Rock Beach (c) Repeal of s150(5) Local Government Act 1972 (d) Penzance & Newlyn Town Framework Steering Group - 16th April 2014 (e) Cemetery Regulations Review (f) Crowlas cemetery headstone 11. -

3. Discover Your Family History…With Kresen Kernow! the Census

Information Classification: CONTROLLED 3. Discover your family history…with Kresen Kernow! The census Every 10 years since 1801 the government has counted everyone in England and Wales. This is known as a census, and censuses are incredibly useful for your family history research. Early censuses contained little detail, but as time went on the information collected increased. You can look at censuses up to 1911 as they are closed for 100 years. The 1921 census will be released in January 2022 – so not too long to wait! This task will show you how to access these records using free sites on the internet. Searching the census The 1801 census was taken to see how many men could be called in to military service in order to fight Napoleon Bonaparte if he invaded from France. The 1811, 1821 and 1831 census are very similar headcounts, but with no further details. The survival of all of these records is very patchy. The 1841 census was taken by the government’s Home Office who were, by then, keen to find out more detail about the population. It was taken on Sunday 6 June 1841. It records every member of the household who was in the house that night, but exact ages only for those under 15. Those older than that were rounded down to the nearest 5 years (e.g. a 44 year old would be recorded as aged 40 years, and a 28 year old would be recorded as 25). Top tip - The census was a record of the people in a household on that night. -

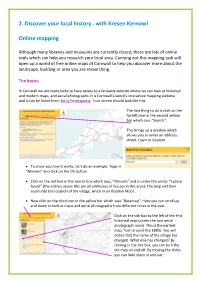

2. Discover Your Local History…With Kresen Kernow! Online Mapping

Information Classification: CONTROLLED 2. Discover your local history…with Kresen Kernow! Online mapping Although many libraries and museums are currently closed, there are lots of online tools which can help you research your local area. Carrying out this mapping task will open up a world of free online maps of Cornwall to help you discover more about the landscape, building or area you are researching. The basics In Cornwall we are really lucky to have access to a fantastic website where we can look at historical and modern maps, and aerial photographs. It is Cornwall Council’s interactive mapping website, and it can be found here: bit.ly/hermapping. Your screen should look like this. The first thing to do is click on the far left icon in the second yellow bar which says “Search”. This brings up a window which allows you to enter an address, street, town or location. • To show you how it works, let’s do an example. Type in “Minions” and click on the OK button. • Click on the last line in the search box which says, “Minions” and is under the words “1 place found” (the entries above this are all addresses of houses in this area). The map will then zoom into the location of the village, which in on Bodmin Moor. • Now click on the third icon in the yellow bar which says “Basemap”. Here you can scroll up and down to look at maps and aerial photographs from different times in the past. Click on the tick box to the left of the first historical map (under the two aerial photograph icons).