Tains a Large Assortment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Catalogue Description and Inventory

= CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION AND INVENTORY Adv.MSS.30.5.22-3 Hutton Drawings National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © 2003 Trustees of the National Library of Scotland = Adv.MSS.30.5.22-23 HUTTON DRAWINGS. A collection consisting of sketches and drawings by Lieut.-General G.H. Hutton, supplemented by a large number of finished drawings (some in colour), a few maps, and some architectural plans and elevations, professionally drawn for him by others, or done as favours by some of his correspondents, together with a number of separately acquired prints, and engraved views cut out from contemporary printed books. The collection, which was previously bound in two large volumes, was subsequently dismounted and the items individually attached to sheets of thick cartridge paper. They are arranged by county in alphabetical order (of the old manner), followed by Orkney and Shetland, and more or less alphabetically within each county. Most of the items depict, whether in whole or in part, medieval churches and other ecclesiastical buildings, but a minority depict castles or other secular dwellings. Most are dated between 1781 and 1792 and between 1811 and 1820, with a few of earlier or later date which Hutton acquired from other sources, and a somewhat larger minority dated 1796, 1801-2, 1805 and 1807. Many, especially the engravings, are undated. For Hutton’s notebooks and sketchbooks, see Adv.MSS.30.5.1-21, 24-26 and 28. For his correspondence and associated papers, see Adv.MSS.29.4.2(i)-(xiii). -

Sweetheart Abbey and Precinct Walls Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC216 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90293) Taken into State care: 1927 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SWEETHEART ABBEY AND PRECINCT WALLS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH SWEETHEART ABBEY SYNOPSIS Sweetheart Abbey is situated in the village of New Abbey, on the A710 6 miles south of Dumfries. The Cistercian abbey was the last to be set up in Scotland. -

The Kingship of David II (1329-71)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository 1 The Kingship of David II (1329-71) Although he was an infant, and English sources would jibe that he soiled the coronation altar, David Bruce was the first king of Scots to receive full coronation and anointment. As such, his installation at Scone abbey on 24 November 1331 was another triumph for his father.1 The terms of the 1328 peace had stipulated that Edward III’s regime should help secure from Avignon both the lifting of Robert I’s excommunication and this parity of rite with the monarchies of England and France. David’s coronation must, then, have blended newly-borrowed traditions with established Scottish inaugural forms: it probably merged the introduction of the boy-king and the carrying of orb, sceptre and sword by the incumbents of ancient lines of earls, then unction and the taking of oaths to common law and church followed by a sermon by the new bishop of St Andrews, the recitation of royal genealogy in Gaelic and general homage, fealty and knighting of subjects alongside the king.2 Yet this display must also have been designed to reinforce the territorial claims of authority of the Bruce house in the presence of its allies and in-laws from the north, west and south-west of Scotland as well as the established Lowland political community. Finally, it was in part an impressive riposte to Edward II’s failed attempts to persuade the papacy of his claim for England’s kings to be anointed with the holy oil of Becket.3 1 Chronica Monasterii de Melsa, ed. -

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar Introduction The Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland from August 14-26, 2014, was organized for Clan Dunbar members with the primary objective to visit sites associated with the Dunbar family history in Scotland. This Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland focused on Dunbar family history at sites in southeast Scotland around Dunbar town and Dunbar Castle, and in the northern highlands and Moray. Lyle Dunbar, a Clan Dunbar member from San Diego, CA, participated in both the 2014 tour, as well as a previous Clan Dunbar 2009 Tour of Scotland, which focused on the Dunbar family history in the southern border regions of Scotland, the northern border regions of England, the Isle of Mann, and the areas in southeast Scotland around the town of Dunbar and Dunbar Castle. The research from the 2009 trip was included in Lyle Dunbar’s book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part I-The Earls of Dunbar, recently published in May, 2014. Part I documented the early Dunbar family history associated with the Earls of Dunbar from the founding of the earldom in 1072, through the forfeiture of the earldom forced by King James I of Scotland in 1435. Lyle Dunbar is in the process of completing a second installment of the book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part II- After the Fall, which will document the history of the Dunbar family in Scotland after the fall of the earldom of Dunbar in 1435, through the mid-1700s, when many Scots, including his ancestors, left Scotland for America. -

Following the Sacred Steps of St. Cuthbert

Folowing te Sacred Stps of St. Cutbert wit Fater Bruce H. Bonner Dats: April 24 – May 5, 2018 10 OVERNIGHT STAYS YOUR TOUR INCLUDES Overnight Flight Round-trip airfare & bus transfers Edinburgh 3 nights 10 nights in handpicked 3-4 star, centrally located hotels Durham 2 nights Buffet breakfast daily, 4 three-course dinners Oxford 2 nights Expert Tour Director London 3 nights Private deluxe motorcoach DAY 1: 4/24/2018 TRAVEL DAY Board your overnight flight to Edinburgh today. DAY 2: 4/25/2018 ARRIVAL IN EDINBURGH Welcome to Scotland! Transfer to your hotel and get settled in before meeting your group at tonight’s welcome dinner. Included meals: dinner Overnight in Edinburgh DAY 3: 4/26/2018 SIGHTSEEING TOUR OF EDINBURGH Get to know Edinburgh in all its medieval beauty on a tour led by a local expert. • View the elegant Georgian-style New Town and the Royal Mile, two UNESCO World Heritage sites • See the King George statue and Bute House, the official residence of the Scottish Prime Minister • Pass the Sir Walter Scott monument • Enter Edinburgh Castle to view the Scottish crown jewels and Stone of Scone Enjoy a free afternoon in Edinburgh to explore the city further on your own. Included Entrance Fees: Edinburgh Castle Included meals: breakfast Overnight in Edinburgh DAY 4: 4/27/2018 STIRLING CASTLE AND WILLIAM WALLACE MONUMENT Visit Stirling, a town steeped in the history of the Wars of Scottish Independence. For generations, Sterling Castle held off British advances and served as a rallying point for rebellious Scots. It was within Stirling Castle that the infant Mary Stewart was crowned Mary, Queen of Scots. -

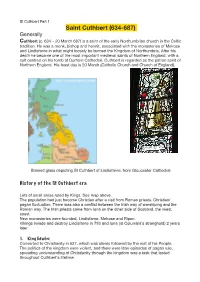

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (C

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (c. 634 – 20 March 687) is a saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in what might loosely be termed the Kingdom of Northumbria. After his death he became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northern England. His feast day is 20 March (Catholic Church and Church of England), Stained glass depicting St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, from Gloucester Cathedral History of the St Cuthbert era Lots of small areas ruled by Kings. See map above. The population had just become Christian after a visit from Roman priests. Christian/ pagan fluctuation. There was also a conflict between the Irish way of worshiping and the Roman way. The Irish priests came from Iona on the other side of Scotland, the /west coast. New monasteries were founded, Lindisfarne, Melrose and Ripon. Vikings invade and destroy Lindisfarne in 793 and Iona (st Columbia’s stronghold) 2 years later. 1. King Edwin: Converted to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by the rest of his People. The politics of the kingdom were violent, and there were later episodes of pagan rule, spreading understanding of Christianity through the kingdom was a task that lasted throughout Cuthbert's lifetime. Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome. -

Download Download

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 139 (2009), 257–304GRAVEHEART: CULT AND BURIAL IN A CISTERCIAN CHAPTER HOUSE | 257 Graveheart: cult and burial in a Cistercian chapter house – excavations at Melrose, 1921 and 1996 Gordon Ewart,* Dennis Gallagher† and Paul Sherman‡ with contributions from Julie Franklin, Bill MacQueen and Jennifer Thoms ABSTRACT The chapter house at Melrose was first excavated by the Ministry of Works in 1921, revealing a sequence of burials including a heart burial, possibly that of Robert I. Part of the site was re-excavated in 1996 by Kirkdale Archaeology for Historic Scotland in order to provide better information for the presentation of the monument. This revealed that the building had expanded in the 13th century, the early chamber being used as a vestibule. There was a complex sequence of burials in varied forms, including a translated bundle burial and some associated with the cult which developed around the tomb of the second abbot, Waltheof. The heart burial was re-examined (and reburied) and its significance is considered in the context of contemporary religious belief and the development of a cult. There was evidence for an elaborate tiled floor, small areas of which survive in situ. INTRODUCTION invitation of King David I. Under its first abbot, Richard (1136–48), the community rapidly The chapter house at Melrose Abbey (NGR: expanded and royal support for their austere NT 5484 3417; illus 1 and 2) was excavated life led to the founding of a daughter house at first in 1921 by the Ministry of Works as part of Newbattle in 1140, soon to be followed by other an extensive clearance of the monastic remains houses (Cowan & Easson 1976, 72). -

Dunfermline Abbey by John Marshall

DUNFERMLINE ABBEY BY JOHN MARSHALL, Late Head Master Townhill Public School. THE JOURNAL PRINTING WORKS 1910 DUNFERMLINE ABBEY BY JOHN MARSHALL, Late Head Master Townhill Public School. PRINTED ON DISC 2013 ISBN 978-1-909634-18-3 THE JOURNAL PRINTING WORKS 1910 Pitcairn Publications. The Genealogy Clinic, 18 Chalmers Street, Dunfermline KY12 8DF Tel: 01383 739344 Email enquiries @pitcairnresearh.com 2 DUNFERMLINE ABBEY BY JOHN MARSHALL Late Head Master Townhill Public School. James Stewart. Swan, engraver. DUNFERMLINE: THE JOURNAL PRINTING WORKS. Dunfermline Carnegie Library. (Local Collection.) 3 CONTENTS. ______ The Abbey: Introduction Page 1. Its Origin. 8 II. The Builders. 11 III. The Buildings. 13 IV. The Donors and the Endowments. 16 V. The Occupants. 20 VI. Two Royal Abbots & Abbots Beaton and Dury. 23 VII. Misfortunes of the Abbey. 25 VIII. The Maligned Reformers. 27 IX. Protestant Care of the Buildings. 29 X. Decay and Repairs. 31 XI. Fall of the Lantern and S. W. Towers, etc. 35 XII. The Interior of the Abbey. 39 XIII. The Royal Tombs. 41 <><><><><><> 4 ILLUSTRATIONS S. PITCAIRN. Page. THE FRONT COVER DUNFERMLINE ABBEY I INTERIOR OF ABBEY NAVE 2 PEDIGREE CHART – RICHARD I 10 AN ARTISTS IMPRESSION OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF DUNFERMLINE ABBEY 12 EARLY CHURCH 14 EARLY ORGAN, DUNFERMLINE, 1250 16 THE TOMB OF MARGARET AND MALCOLM SURROUNDED BY RAILINGS. 17 BENEDICTINE MONK 22 THE GREAT ABBEY OF DUNFERMLINE, 1250 29 DUNFERMLINE ABBEY, c. 1650 31 ABBEY NAVE 35 WEST DOORWAY 37 ROBERT HENRYSON’S “TESTAMENT OF CRESSEID” 39 WINDOWS 49 DUNFERMLINE ABBEY 43 ALEXANDER III 45 ROBERT BRUCE BODY 46 ARMS OF QUEEN ANNABELLA DRUMMOND 47 DUNFERMLINE ABBEY CHURCHYARD 48 <><><><><><> 5 DUNFERMLINE ABBEY _________ INTRODUCTION. -

Investigating Melrose Abbey

Melrose Abbey is one of the most beautiful of all Scotland’s abbeys. Its INVESTIGatinG tranquil setting at the foot of the Eildon Hills gives little MElrosE ABBEY hint of the turbulent events which took place here. Information for Teachers investigating historic sites HISTORIC SCOTLAND education Melrose Abbey 2 Historical background of this wealth stemmed from donations from pious nobles, investing heavily in The story of Melrose abbey begins the afterlife, but much of it came from Timeline more than 1,300 years ago and about the wool trade. At its height in the 14th 650 St Aidan founds 4km to the east of its present setting. century, the monks of Melrose owned Mailros monastery at Old Around 650 AD monks from Lindisfarne 15,000 sheep, one of the biggest flocks Melrose established a monastery within a turn in Britain. 839 Old Melrose of the River Tweed, at a place known destroyed by Kenneth as Mailros. At that time this was part of The peaceful round of prayer came to MacAlpin the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria. an abrupt end in 1296 when Scotland 1136 Cistercian monks The young St Cuthbert entered the was invaded by Edward I. The abbey from Rievaulx set up new monastery, becoming its prior before was sacked by Edward II in 1322, rebuilt monastery on site of becoming prior of Lindisfarne in 664. with the assistance of Robert the Bruce modern Melrose Only traces of this original abbey and was again destroyed by Richard 1296 Edward I invades remain; most of it was destroyed in 839 II in 1357. -

Melrose Abbey and St Mary of Melrose - Roxburghshire, Scotland and William De Douglas 1St Lord of Douglas

Melrose Abbey and St Mary of Melrose - Roxburghshire, Scotland and William de Douglas 1st Lord of Douglas ‘The church of the convent was dedicated to St. Mary (like all Cistercian houses) on 28 July 1146’. (Wikipedia) Seeking historical information on William de Douglas 1st Lord of Douglas? Was William de Douglas c1174 to c1214, in fact the first Douglas who can be traced in Scottish history or was he in fact about the 3rd Lord of Douglas. What was William’s connection with Melrose Abbey – William de Douglas c1174 witnessed a charter by Jocelin the Bishop of Glasgow (see below) who had previously been Abbot of Melrose Abbey and William, between 1174 and 1199, possibly became Abbot of Melrose Abbey? Was there an earlier William de Douglas who was the Abbot of Melrose as well? In 1162 a ‘William abbot of Melros’ (Melrose) was a Witness to a Charter by Malcolm, King of the Scots, granting lands to Newbattle Abbey – National Records of Scotland GD1/194/2/1. How did William de Douglas c1174 manage to be an Abbot and marry Margaret de Kerdal of Moray c1177 and have seven children? Did he leave the order of the Cistercians or white monks in order to marry? What I am doing here is asking some questions and compiling some key sources about the early days of Melrose Abbey. William de Douglas 1st Lord of Douglas c1174 Douglas Castle, Douglas, Lanarkshire, Scotland was a Scottish Knight and witness to a Charter of Jocelin/Joselin/Jocelyn, who was Bishop of Glasgow in 1174. -

Story of Robert the Bruce

Conditions and Terms of Use Copyright © Heritage History 2010 Some rights reserved This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. PREFACE The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. "Ah, Freedom is a noble thing! They may therefore be reproduced within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. Freedom makes a man to have liking [pleasure]; Freedom all solace to man gives; The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, He lives at ease that freely lives!" however, are the property of Heritage History and are subject to certain restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting These words were written by a poet who lived in the the integrity of the work, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure that compromised versions of the work are not widely days of Bruce, and who kept for us the story of his life and disseminated. adventures. In order to preserve information regarding the origin of this It is to Robert the Bruce that we who live north of text, a copyright by the author, and a Heritage History distribution date the Tweed owe our freedom. are included at the foot of every page of text. We require all electronic and printed versions of this text include these markings and that users More than that we owe to him.