1 UNIT 3 BUDDHISM – II Contents 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Remarks About the History of the Sarvāstivāda Buddhism

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXVII, Z. 1, 2014, (s. 255–268) CHARLES WILLEMEN Remarks about the History of the Sarvāstivāda Buddhism Abstract Study about the history of a specific Buddhist monastic lineage known as “Sarvāstivāda” based on an overview of the history of its literature. Keywords: Sarvāstivāda, Buddhism, schism, Mahāyāna, Abhidharma, India, Gandhāra All scholars agree that the Sarvāstivāda (“Proclaiming that Everything Exists”) Buddhism was strong in India’s north-western cultural area. All agree that there was the first and seminal schism between the Sthaviravāda and the Mahāsāṅghika. However, many questions still remain to be answered. For instance, when did the first schism take place? Where exactly in India’s north-western area? We know what the Theravāda tradition has to say, but this is the voice of just one Buddhist tradition. Jibin 罽賓 The Chinese term Jibin is used to designate the north-western cultural area of India. For many years it has been maintained by Buddhist scholars that it is a phonetic rendering of a Prakrit word for Kaśmīra. In 2009 Seishi Karashima wrote that Jibin is a Chinese phonetic rendering of Kaśpīr, a Gāndhārī form of Kaśmīra.1 In 1993 Fumio Enomoto postulated that Jibin is a phonetic rendering of Kapiśa (Kāpiśī, Bagram).2 Historians have long held a different view. In his article of 1996 János Harmatta said that in the seventh century Jibin denoted the Kapiśa-Gandhāra area.3 For this opinion he relied on 1 Karashima 2009: 56–57. 2 Enomoto 1993: 265–266. 3 Harmatta (1996) 1999: 371, 373–379. 256 CHARLES WILLEMEN Édouard Chavannes’s work published in 1903. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’S Mentality

International Conference of Electrical, Automation and Mechanical Engineering (EAME 2015) The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’s Mentality X.H. Li School of literature and Journalism Shandong University Jinan China Abstract—In order to study the influence of Buddhism, most of A. Sukhavati: Maitreya and MiTuo the temples and document in china were investigated. The results Hui Yuan and Daolin Zhi also have faith in Sukhavati. indicated that Buddhism developed rapidly in Southern dynasty. Sukhavati is the world where Buddha live. Since there are Along with the translation of Buddhist scriptures, there were lots many Buddha, there are also kinds of Sukhavati. In Southern of theories about Buddhism at that time. The most popular Dynasty the most prevalent is maitreya pure land and MiTuo Buddhist theories were Prajna, Sukhavati and Nirvana. All those theories have important influence on Nan dynasty’s literati, pure land. especially on their mentality. They were quite different from The advocacy of maitreya pure land is Daolin Zhi while literati of former dynasties: their attitude toward death, work Hui Yuan is the supporter of MiTuo pure land. Hui Yuan’s and nature are more broad-minded. All those factors are MiTuo pure land wins for its simple practice and beautiful displayed in their poems. story. According to < Amitabha Sutra>, Sukhavati is a perfect world with wonderful flowers and music, decorated by all Keyword-the evolvement of buddhism; southern dynasty; kinds of jewelry. And it is so easy for every one to enter this literati’s mentality paradise only by chanting Amitabha’s name for seven days[2] . -

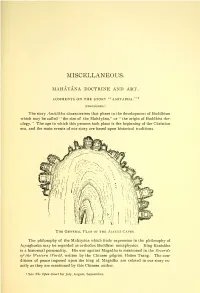

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

The Kayas / Bodies of a Buddha

The Kayas / Bodies of a Buddha The original meaning of the Sanskrit word Kaya (Tibetan: sku/ku) is 'that which is accumulated'. In English Kaya is translated as 'body'. However, the Kayas of Buddhas do not literally refer only to the form aggregates of Buddhas but also to Buddhas themselves, to their various attributes, and so forth. There are different ways to categorize Kayas: 1. The category into five Kayas 2. The category into four Kayas 3. The category into three Kayas 4. The category into two Kayas 1. The category into five Kayas The category into five Kayas refers to: I. The Dharmakaya / Truth Body (chos sku / choe ku) II. The Svabhavakaya / Nature Body (ngo bo nyid sku / ngo wo nyi ku) III. The Jnanakaya / Wisdom Truth Body (ye shes chos sku / ye she choe ku) IV. The Sambhogakaya / Enjoyment Body (longs sku / long ku) V. The Nimanakaya / Emanation Body (sprul sku / truel ku) Here the basis of the category is Kaya, which means that Kaya is categorized or classified into the five Kayas. I. The Dharmakaya / Truth Body Kaya and Dharmakaya are synonymous. Whatever is a Kaya is necessarily a Dharmakaya and vice versa. The definition of a Dharmakaya is: a final Kaya that is attained in dependence on meditating on its attaining agents, the three exalted knowers. The three exalted knowers are: a) Knower of basis (the Arya paths in the continua of Hearers and Solitary Realizers) b) Knower of paths (the Arya paths in the continua of Buddhas and of Bodhisattvas who have reached the Mahayana path of seeing or the Mahayana path of meditation) c) Exalted knower of aspects (the Arya paths, that is, omniscient mental consciousnesses, in the continua of Buddhas) II. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Text, History, and Philosophy Abhidharma Across Buddhist Scholastic Traditions

iii Text, History, and Philosophy Abhidharma across Buddhist Scholastic Traditions Edited by Bart Dessein Weijen Teng LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV ContentsContents vii Contents Preface ix List of Figure and Tables xi Notes on Contributors xii Introduction 1 Part 1 Mātṛkā and Abhidharma Terminologies 1 Abhidharma and Indian thinking 29 Johannes Bronkhorst 2 Abhidharmic Elements in Gandhāran Mahāyāna Buddhism: Groups of Four and the abhedyaprasādas in the Bajaur Mahāyāna Sūtra 47 Andrea Schlosser and Ingo Strauch 3 Interpretations of the Terms ajjhattaṃ and bahiddhā: From the Pāli Nikāyas to the Abhidhamma 108 Tamara Ditrich 4 Some Remarks on the Proofs of the “Store Mind” (Ālayavijñāna) and the Development of the Concept of Manas 146 Jowita Kramer Part 2 Intellectual History 5 Sanskrit Abhidharma Literature of the Mahāvihāravāsins 169 Lance S. Cousins 6 The Contribution of Saṃghabhadra to Our Understanding of Abhidharma Doctrines 223 KL Dhammajoti For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV viii Contents 7 Pratītyasamutpāda in the Translations of An Shigao and the Writings of His Chinese Followers 248 Eric M. Greene 8 Abhidharma in China: Reflections on ‘Matching Meanings’ and Xuanxue 279 Bart Dessein 9 Kuiji’s Abhidharmic Recontextualization of Chinese Buddhism 296 Weijen Teng 10 Traces of Abhidharma in the bSam-gtan mig-sgron (Tibet, Tenth Century) 314 Contents Dylan Esler Contents vii Preface ix List of Figure and Tables xi Notes on Contributors xii Introduction 1 Part 1 Mātṛkā -

The Changeless Nature

The Changeless Nature MAHAYANA UTTARA TANTRA SASTRA by Arya Maitreya & Acarya Asanga TRANSLATED FROM THE TIBETAN BY KEN & KATIA HOLMES "The Ultimate Mahayana Treatise on The Changeless Continuity of the True Nature" The Changeless Nature (the mahayanottaratantrasastra) by Arya Maitreya and Acarya Asanga translated from the Tibetan under the guidance of Khenchen the IXth Trangu Rinpoche and Khempo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche by Kenneth Holmes and Katia Holmes M. A., M. Sc with the kind assistance of Dharmacarya Tenpa Negi KARMA DRUBGYUD DARJAY LING Published in Scotland by: Karma Drubgyud Darjay Ling (Karma Kagyu Trust), Kagyu Samye Ling Tibetan Centre Eskdalemuir, Dumfriesshire DG13 OQL. © Copyright K. & CMS. A. Holmes All rights reserved. No reproduction by any known means, or re-translation, in part or on whole, without prior written permission. Second Edition 1985 ISBN 0906181 05 4 Typeset and printed at Kagyu Samye Ling Bound by Crawford Brothers Newcastle. Illustrations: Frontispiece: Jamgon Kongtrul the Great page 14: Maitreya and Asanga Back page: His Holiness the XVIth Gyalwa Karmapa The illustrations for each of the vajra points were chosen by Khenchen Trangu Rinpoche, as was the banner emblem on the cover of all this series of our books. The banner symbolises victory over the senses. All line drawings by Sherapalden Beru of Kagyu Samye Ling, © Copyright Karma Drubgyud Darjay Ling, Scotland 1979. No reproduction without prior written permission. This book is especially dedicated to the swift enthronement of His Holiness the XVIIth Gyalwa Karmapa and that the precious dharma work of all the Buddhist teachers and their assistants flourish without obstacle to bring peace to this and all worlds. -

The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra (2Nd Edition)

TheThe PrajnaPrajna ParamitaParamita HeartHeart SutraSutra Translated by Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary by Grand Master T'an Hsu English Translation by Ven. Master Lok To Second Edition 2000 HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese By Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary By Grand Master T’an Hsu Translated Into English By Venerable Dharma Master Lok To Edited by K’un Li, Shih and Dr. Frank G. French Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada New York – San Francisco – Toronto 2000 First published 1995 Second Edition 2000 Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada Dharma Master Lok To, Director 2611 Davidson Ave. Bronx, New York 10468 (USA) Tel. (718) 584-0621 2 Other Works by the Committee: 1. The Buddhist Liturgy 2. The Sutra of Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha’s Fundamental Vows 3. The Dharma of Mind Transmission 4. The Practice of Bodhisattva Dharma 5. An Exhortation to Be Alert to the Dharma 6. A Composition Urging the Generation of the Bodhi Mind 7. Practice and Attain Sudden Enlightenment 8. Pure Land Buddhism: Dialogues with Ancient Masters 9. Pure-Land Zen, Zen Pure-Land 10. Pure Land of the Patriarchs 11. Horizontal Escape: Pure Land Buddhism in Theory & Practice. 12. Mind Transmission Seals 13. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra 14. Pure Land, Pure Mind 15. Bouddhisme, Sagesse et Foi 16. Entering the Tao of Sudden Enlightenment 17. The Direct Approach to Buddhadharma 18. -

Address and Contact Information Drikung Kyobpa Choling (Tibetan

Retreat at DKC with Khenchen Gyaltshen Rinpoche Samsara and Nirvana: Two Sides of the Same Hand 10am – 5pm Saturday and Sunday August 11th and 12th Friday evening talk 7pm August 10th — Saturday Evening: 7pm Dharma Protectors Practice The village of Tsari and the surrounding areas are amount the most sacred places in Tibet. It was there that Khenchen Rinpoche was born in the spring of 1946. In 1960, because of the political situation in Tibet, Khenchen Rinpoche fled to India with his family. They settled in Darjeeling, where he began his education. Even at a young age, he was an excellent and dedicated student, and he was able to complete his middle school studies in less than that average time. Around the time he completed middle school, a new university, the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, opened in Varanasi, India and Khenchen Rinpoche traveled to Varanasi in 1967 to seek admission. There he began a nine year course of study that included Madhyamaka, Abhidharma, Vinaya, the Abhisamayalankara, and the Uttarartantra, as well as history, logic and Tibetan grammar. In 1968, he had the good fortune to take ordination with the great Kalu Rinpoche and shortly after graduating from the Institute, he received teachings from the 16th Karmapa on The Eight Treasures of Mahamudra Songs. Even after completing this long and arduous study, Khenchen Rinpoche wanted only to deepen his knowledge and practice of the Dharma, and thus he sought out and received teachings and instructions from great Buddhist masters. Thus, with the Venerable Khunu Lama Rinpoche, he studied The Jewel ornament of Liberation, The Precious Garland of the Excellent Path, teachings on Mahamudra and many songs of Milarepa. -

The Second Chapter of the Pramanavarttika

The Second Chapter of the Pramanavarttika Handout for the Fall 2014 Term for the Advanced Buddhist Philosophy Course in English INSTITUTE OF BUDDHIST DIALECTICS McLeod GanJ, Dharamsala, India Prepared by Venerable Kelsang Wangmo Table of Contents1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Dignaga ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Dharmakirti ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Gyaltsab Je ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 The Seven Treatises on Pramana ................................................................................................................................... 4 The eight pivotal points of logic ...................................................................................................................................... 5 The Pramanavarttika ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 The chapter on inference for one’s own benefit ....................................................................................................