Analytical Corrections, Additions and Enhancements for Alekhine's The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keep Politics out Of

WCffTVX! COPf STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE WEDNESDAY, 25th JANUARY, 1984 No. 701 Price 10p Student poll reveals startling facts . Hall catering under attack KEEP POLITICS at meeting One might assume from the low turnout to the General Meeting on accommodation that everyone is happy with both university and private accommodation facilities. OUT OF IT! However, the comments from the 56 people who did turn up were far from complimentary. A poll of students at Newcastle University shows that a large majority believe that General MeetAlthough the meeting was inquorate there was no problem ings should concentrate on “ purely student issues” and that membership of the National making the discussion last the full hour, with complaints being Union of Students should be a decision taken by the individual and not by Student Unions. centred on the Halls of Residence and Castle Leazes in particular. This information comes When asked: “Should member that their grant is “adequate”. voters, but this might explain the Out of a debate which centred ship of N.U.S. be voluntary?”, This may reflect the fact that the extraordinary difference between around the price of living in Hall from the results of a poll 78% said yes and 20% said it respondents were mainly First this poll and the national average and the facilities provided came a carried out by Conserva should be compulsory. If this is Years and have not yet run out of for the Labour ‘vote’. practically unanimous agreement looked at in conjunction with the money, or that the answer comes that meal vouchers should be tive students (F.C.S.). -

SDSU Template, Version 11.1

USING CHESS AS A TOOL FOR PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION _______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University _______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Sociology _______________ by Haroutun Bursalyan Summer 2016 iii Copyright © 2016 by Haroutun Bursalyan All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION To my wife, Micki. v We learn by chess the habit of not being discouraged by present bad appearances in the state of our affairs, the habit of hoping for a favorable change, and that of persevering in the search of resources. The game is so full of events, there is such a variety of turns in it, the fortune of it is so subject to sudden vicissitudes, and one so frequently, after long contemplation, discovers the means of extricating one's self from a supposed insurmountable difficulty.... - Benjamin Franklin The Morals of Chess (1799) vi ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Using Chess as a Tool for Progressive Education by Haroutun Bursalyan Master of Arts in Sociology San Diego State University, 2016 This thesis will look at the flaws in the current public education model, and use John Dewey’s progressive education reform theories and the theory of gamification as the framework to explain how and why chess can be a preferable alternative to teach these subjects. Using chess as a tool to teach the overt curriculum can help improve certain cognitive skills, as well as having the potential to propel philosophical ideas and stimulate alternative ways of thought. The goal is to help, however minimally, transform children’s experiences within the schooling institution from one of boredom and detachment to one of curiosity and excitement. -

A THIRD CROWN for BENKO • \ Sf'i' J1 63 J

A THIRD CROWN FOR BENKO • \ Sf'I' J1 63 J .:. UNITED STATES Va:"me XX I N u mb ~ r 3 l la rch, 1966 EDITOR: J . F. Reinhardl CO"'TE"'TS CHESS FEDERATION A Third Crown for Benko ..... ............... .... ............................ ...... .. .. .......... .. 63 Two from the Championship, by Pol Benko .............. .... .... .. ... ... .. ............ ..64 PRESIDENT Lt. Col. E. B. Edmondson My Championship Brilliancy, by Robert Byrne .... ............ .. .. .. .... .... .... .. .. .... 66 VICE·PRF.SID£NT "Old Hot!" by Dr . A. F. Soidy ........... ..... ............ ..... ..... ............... ..... .. .. ... .68 David HoHmann REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS Spossky-Tol, by Bernard Zucke rman .... ........ ................ .. ... .. ... ....... .. .. ... .. .70' NEW ENGLAND Stln}ey Klnll lI.mld Dondls Gomes by USC F Members, by John W . Collins ... .. .. ........ .. .. .. ... .... ...... ... .....73 .:11 !Jourdon EASTERN Donald Schultz Here & There .... .. ..... ... ................ ....... ..... ........ .. ..... .. ..... ..... ......... .. ... ....... 75 Lewis E. Wood 1I 0bert LalJcJle MID_ATLANTIC William IIragg His Majesty Steps Out, by Pol Benko ... .. ..... ...... .. ..... .. ... .. .. .... ................. .76 Earl CItifY .:dw". d O. Strehle Tournament Life ......... .. .......... .. ... ... ........ ..... .... ..... .. .... ........ ................ ..... 77 SOUTHERN Or. Roberl .' roemke Puler I.ahdc Carroll lI-l. Crull GREAT LAKES Norbert Matlhew, Donald W. IIIldlng Or. lIarv"y MtCle lla" NORTH CENTRAL Kober! Lerner J ohn O$neu Ken -

All Puzzles - Chess.Pdf

Tonight • We’re here to help! This is not a competitive event. Ask the Game Control volunteers (GC) for hints as often as you’d like. The goal is to have fun, not to be frustrated! • If your location is running virtual, go to the location page and find out how to contact your local GC. It’s located at: http://puzzledpint.com/june-2021/chess/gambit • If you would like to solve online, there is a Google Sheet you and your team can use at: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/18In6wvRRI1uN9N-dLTK9nY2dc-_UW6t_nYggGo_LFkU/ The Puzzles • Each puzzle will solve to a short word or phrase. How? That’s for you to discover! • Need a code sheet or solving resources? Check out the Resources page on Puzzled Pint’s webpage: http://www.puzzledpint.com/resources/ • You can use anything to help solve: Use your phone; the internet is fair game! Think your brother might have an insight? Give him a call! • While each month has a theme, you need no special knowledge of the theme to solve. About Puzzled Pint • How did tonight go? Email us at [email protected] • We’re an all-volunteer organization. • Help us run locally: Talk with Game Control about how you can volunteer. • Help us run globally: https://www.patreon.com/PuzzledPint • How did tonight go? Take a 1 minute survey using this QR code or Email us at [email protected]! Team Name: Start Time: Team Size: End Time: Puzzle Answers The Chess Board Bishops The King’s Walk Setting Up A Game Your First Game (Meta) Lesson A1: THE CHESS BOARD Every tile on the chess board has its own unique name. -

Mixing Time of a Rook's Walk

Mixing Time of a Rook's Walk Steven S. Kim April 2012 Advisor: Michael Damron Independent work for undergraduate certificate, Program in Applied and Computational Mathematics Contents 0 Introduction 1 1 Review of Mixing Times 1 2 The Rook's Walk 3 3 Computations 7 4 Applications 9 5 Future Directions 10 0 Introduction Markov chains, or Markov processes with finite (or countable) state space and discrete time scale, have long been studied for their many applications in engineering and the sciences. Ergodic chains in particular are known to eventually reach stationary distribution, but a natural question arises of how quickly a Markov chain gets \close" to its invariant distribu- tion. In this work, I will first briefly review the theory of mixing times, and then apply one particular technique of bounding mixing time to a Markov chain called the \rook's walk". Consider the movement of a chess piece on an otherwise empty board, and at each time, let it move randomly to any of its valid positions. I consider the rook in particular for three reasons. i. There is a potentially interesting application to a specific MCMC sampling algorithm that will be discussed in a later section. ii. It is particularly natural to generalize the movement of a rook to larger chessboards and higher dimensions. Compare this to a piece like a queen, for which the \diagonal" movement would have to be specified in higher dimensions. iii. The rook does not suffer from the \boundary" conditions that a knight or a king might. For example, a rook on a standard 8 × 8 chessboard has 15 valid positions to move to, even if it is at the edge of the board; on the other hand, a knight or a king has very different valid moves when it is at the center as compared to the edge. -

Texas Grade Championships

The official publication of the Texas Chess Association Volume 58, Number 2 P.O. Box 151804, Ft. Worth, TX 76108 Nov-Dec 2016 $4 Texas Grade Championships Happy Holidays! Table of Contents From the Desk of the TCA President .................................................................................................................. 4 20th Annual Texas Grade Championships .......................................................................................................... 6 En Passant by Jim Hollingsworth ..................................................................................................................... 14 Tactics Time! by Tim Brennan (answers on page 18) .................................................................................. 15 Leader List ....................................................................................................................................................... 16 Brazos Tournament by Jim Hollingsworth........................................................................................................ 19 Coach’s Corner - e4! by Robert L. Myers .......................................................................................................... 26 Upcoming Events ............................................................................................................................................ 30 facebook.com/TexasChess texaschess.org TEXAS CHESS ASSOCIATION www.texaschess.org President: Eddie Rios, [email protected]. Vice-President: Forrest Marler, [email protected]. -

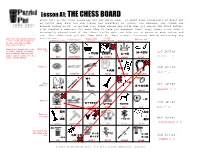

THE CHESS BOARD Every Tile on the Chess Board Has Its Own Unique Name

Lesson A1: THE CHESS BOARD Every tile on the chess board has its own unique name. It might look complicated at first but as you’ll see, each row and column has something in common. For example, one column has animals hiding in it. In another row, tiles become new words when you remove the first letter. I’ve created a mnemonic for each tile to help you remember them… only, hmmm, looks like I incorrectly placed some of the tiles. You’ll spot one tile out of place in each column and row. Just make sure you put them back in their correct locations before extracting any Each row and column follows conclusions. Female Compound word Words contain Past tense verb a rule, with the exception Sounds like a letter an animal gendered words Related to colors of one tile that’s been moved out of place. Moving the misplaced tiles Starts with a to their correct location, “B” 1st letter H➜BU then indexing them by the -TUB LAND➜S C➜B number given results in the BRIDE = B final answer BISHOP. BEE BASKETBALL BATH GREENS BROWN BUILT LA ↓ Palindrome 2nd letter RE +AM DID = I EYE RACECAR KAYAK MADAM REDDER HORSESHOE W+ Has a U+ +D 6th letter double “E” S➜AGR ➜ SUNDAY al e SATURDAY & GREENS = S SEE WEEKEND WHEEL QUEEN UPEND AGREED Ends in Y -p ➜ 2nd letter W TEGY U➜O -HOUND BRIDE ASHTRAY STRATEGY MOMMY GREY LAY WHY = H En AG Ends in an ↓ ↓ “oo” sound 8th letter ue Y? -TOOTH EW HORSESHOE = O QUEUE CORKSCREW WHY EWE BLUE FLEW O+ Removing the first letter makes a new C➜S C➜D word ➜ =? 2nd letter CE d N➜LY ➜ -LL RED+YELLOW E K OWE DID SLOWLY WITCH ORANGE DRANK UPEND = P © 2021 CC BY-NC-SA Intl. -

Chess Life 11/10/11 8:28 PM Page 4

January 2012 uschess.org A USCF Publication $3.95 IFC:Layout 1 12/9/2011 9:25 AM Page 1 2011_allgirls_ad_DL_r5_chess life 11/10/11 8:28 PM Page 4 in association with P TheThe EighthNinth Annual All-Girls Open National Championships AprilApril 8–10, 20 – 22, 2011 2012 – Chicago,- Chicago, IllinoisIllinois Awards Hotel Swissotel Hotel; 323 E. Wacker Dr, Trophies will be awarded to the top 15 individual players and top three teams in Doubletree Chicago Magnificent Mile, Chicago, IL 60601 300 East Ohio St, Chicago, IL 60611 each section. Three or more players from the same school make up a team (team Hotel Chess Rate: scores will be calculated based on the top 3 scores to give teams their final stand- $169$139 by if Marchreserved 15, by 2012 March 11, 2011 ings). All players will receive a souvenir to honor their participation. Breakfast included. Trophies to top 15 individuals and top 3 teams in each section. 3 or more players Hotel Reservations: from the same school to make a team (top 3 scores added to give team final stand- Please call (312)888-737-9477 787-6100 ings).MAIN Every EVENT player receives a souvenir. SIDE EVENTS Friday, April 20 Bughouse Tournament Friday, April 8 Entry & Info 6:00 PM Opening Ceremony Friday,Friday April 208, 1:00 PM MAIN EVENT SIDE EVENTS Make checks payable to: Entry fee: $25 per team 6:30 PM Round 1 RKnights, Attn: All Girls, Friday, April 8 Bughouse Tournament PO Box 1074, Northbrook, IL 60065 Saturday,Saturday,6:00 PM April April Opening 21 9 Ceremony BlitzFriday Tournament April 8, 1:00 (G/5) PM Tel: -

A Strategic Chess Opening Repertoire for White Ebook

A STRATEGIC CHESS OPENING REPERTOIRE FOR WHITE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Watson | 208 pages | 15 Jun 2012 | Gambit Publications Ltd | 9781906454302 | English | London, United Kingdom A Strategic Chess Opening Repertoire for White PDF Book Your email. I would suggest reading the reviews on amazon to see if it is suitable. We're talking about a rated player. Magnus Carlsen is an embracement badenwurtca 11 min ago. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Secure payments Our whole store and checkout is fully encrypted. Good luck. Known as a "Cooling off period". Repertoire books like these are not so relevant at your level, but this may be something to aim for in the long run. He is up to the task. Moreover, it is a repertoire that will stand the test of time. The repertoire is based on 1 d4 and 2 c4, following up with methodical play in the centre. Many of the recommendations overlap and I think his approach against the solid main lines is very sensible. Watson uses his vast opening knowledge to pick cunning move-orders and poisonous sequences that will force opponents to think for themselves, providing a true test of chess understanding. The repertoire is based on 1 d4 and 2 c4, following up with methodical play in the centre. We will refund the cost of return postage using standard first or second class post. These dark forces are gaining strength and planning to destroy the few remaining White Lights, Gambit Publications. Home 1 Books 2. Overview Such has been the acclaim for John Watson's ground-breaking works on modern chess strategy and his insightful opening books, that it is only natural that he now presents a strategic opening repertoire. -

Ch Jan2011j Layout 1

January-March 2011 $3.95 21st Massachusetts Game/60 Championship Sunday, April 17th, 2011 • Leominster, Massachusetts $1600 in Projected Prizes, $1200 Guaranteed Where: Four Points by Sheraton, 99 Erdman Way, Leominster MA 01453, (978) 534-9000. What: 4-round USCF rated Swiss, Game/60, in 5 sections: Open, U2000, U1800, U1500, U1200. Registration: 8:30 – 9:30 AM Rounds: 10:00 AM, 1:00 PM, 3:30 PM, 6:00 PM. Entry Fee: $34 if received by mail or online (PayPal) at www.masschess.org by 4/15, $40 at site. $10 discount to unrated and players in U1200. GMs and IMs free. No phone/email entries. Special: Unrated may play in any section but may not win 1st prize except in the Open section. Prizes: Prizes are 75% guaranteed based on 70 players. Open: $250-150 U2150 $100 6 Grand Prix Points U2000: $200-100 U1800: $150-75 U1650 $75 U1500: $150-75 U1350 $75 U1200: $150-50 U1000 $50 • One half-point bye allowed in any round if requested with entry. Limit one bye. • USCF and MACA required. (MACA dues $12 adult, $6 under 18; add $8 [optional] for a subscription to Chess Horizons) Questions: Bob Messenger. Phone (603) 891-2484 or send email to [email protected]. 21st Massachusetts Game/60 Championship, April 17th, 2011 Name: __________________________________________________ USCF #___________________ Exp: ________ Address: __________________________________________________ Phone: __________________ Rating: ______ City/State/Zip: _________________________________________________________________________________ Email Address: _________________________________________ Junior MACA - Date of Birth: ________________ Need USCF membership? Yes / No Enclosed for USCF is $ ________ Need MACA membership? Yes / No Enclosed for MACA is $ ________ Adult: $12, Junior (under 18) $6 (add $8 for Chess Horizons [optional]) Entry Fee $ ________ for the ___________________section (please specify section) Total Enclosed $ ________ Mail checks, payable to MACA, to: Bob Messenger, 4 Hamlett Dr. -

Ohio Chess Bulletin May 2015

Ohio Chess Bulletin Volume 68 May 2015 Number 3 OCA Officers The Ohio Chess Bulletin published by the President: Evan Shelton 8241 Turret Dr. Ohio Chess Association Blacklick OH 43004 (614)-425-6514 Visit the OCA Web Site at http://www.ohchess.org [email protected] Vice President: Riley Driver 18 W. 5th St - Mezzanine Dayton, OH 45402 (937) 461-6283 [email protected] Secretary: Grant Neilley 2720 Airport Drive Columbus, OH 43219-2219 (614)-418-1775 [email protected] Treasurer/Membership Chair: Cheryl Stagg 7578 Chancery Dr. Dublin, OH 43016 (614) 282-2151 Ohio Chess Association Trustees [email protected] District Name Address / Phone / E-mail OCB Editor: Michael L. Steve 1 Cuneyd 5653 Olde Post Rd # Syvania 43560 3380 Brandonbury Way Tolek (419) 376-7891 # [email protected] Columbus, OH 43232-6170 (614) 833-0611 2 Fred 132 E. Second St. # Pt Clinton 43452 [email protected] Schwan (419) 349-1872# [email protected] Webmaster: 3 Chris P.O. Box 834 # Richmond, IN 47375 Joe Yun Bechtold (765) 993-9218 # [email protected] 7125 Laurelview Circle NE Canton, OH 44721-2851 4 Eric 1799 Franklin Ave # Columbus 43205 (330) 705-7598 Gittrich (614)-843-4300 # [email protected] [email protected] 5 Joseph E. 7125 Laurelview Circle NE # Canton 44721 Inside this issue... Yun (330) 705-7598 # [email protected] 6 Riley D. 18 W. Fifth Street – Mezzanine # Dayton 45402 Points of Contact 2 Driver (937) 461-6283 # [email protected] Message from the President 3 OCA Champions – Who Knew? 4 7 Steve 528 Acton Rd # Columbus 43214 Tournament Count, First Quarter 4 # MOTCF Report 5-9 Charles (614) 309-9028 [email protected] Ohio Senior Open 10 2015 Cardinal Endgame by Boor 11-14 8 Grant 2720 Airport Dr # Columbus 43219-2219 # Running List of OCA Champions 14 Neilley (614)-418-1775 [email protected] 2016 Columbus Open 15 9 Duane 1092 Hempstead Dr # Cincinnati 45231 Carl Boor’s Selected Games 16-18 Larkin (513) 237-1053 # [email protected] Honoring the 1965 Ohio Champion 18 Chess on TV: Bewitched 19 10 Patrick 8707 Glencanyon Dr. -

The Works of Dr. John Tillotson, Late Archbishop of Canterbury. Vol

The Works of Dr. John Tillotson, Late Archbishop of Canterbury. Vol. 10. Author(s): Tillotson, John, (1630-1694) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Volume X. contains Sermons CCXLV-CCLIV, Prayers, A Form of Prayers, and ªThe Rule of Faith.º i Contents Title Page. 1 Prefatory Material. 3 Contents to Vol. X. 3 Sermons. 4 Sermon CCXLV. The Grounds of Bad Men’s Enmity to the Truth. 5 Sermon CCXLVI. True Liberty the Result of Christianity. 14 Sermon CCXLVII. The Duty of Improving the Present Opportunity and 24 Advantages of the Gospel. Sermon CCXLVIII. The Folly of Hazarding Eternal Life for Temporal Enjoyments. 34 Sermon CCXLIX. The Reasonableness of Fearing God More than Man. 44 Sermon CCL. The Reasonableness of Fearing God More than Man. 52 Sermon CCLI. The Efficacy of Prayer for Obtaining the Holy Spirit. 58 Sermon CCLII. The Efficacy of Prayer, for Obtaining the Holy Spirit. 68 Sermon CCLIII. The Bad and Good Use of God’s Signal Judgments upon Others. 77 Sermon CCLIV. Of the Rule of Equity to be Observed Among Men. 91 To the Reader. 110 Prayers, Composed by Archbishop Tillotson. To Which Is Added, a Short Discourse 111 to His Servants Before the Sacrament. A Prayer before the Sermon. 112 A Prayer which (it is conjectured) he used before composing his Sermons. 114 Prayers used by him the Day before his Consecration. 115 A Discourse to his Servants, concerning receiving the Sacrament. 121 A Form of Prayers, Used by His Late Majesty KIng William III. When He Received 122 the Holy Sacrament, and on Other Occasions.