Light Exposure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 3: the Sensor

4.430 Daylighting Human Eye ‘HDR the old fashioned way’ (Niemasz) Massachusetts Institute of Technology ChriChristoph RstophReeiinhartnhart Department of Architecture 4.4.430 The430The SeSensnsoror Building Technology Program Happy Valentine’s Day Sun Shining on a Praline Box on February 14th at 9.30 AM in Boston. 1 Happy Valentine’s Day Falsecolor luminance map Light and Human Vision 2 Human Eye Outside view of a human eye Ophtalmogram of a human retina Retina has three types of photoreceptors: Cones, Rods and Ganglion Cells Day and Night Vision Photopic (DaytimeVision): The cones of the eye are of three different types representing the three primary colors, red, green and blue (>3 cd/m2). Scotopic (Night Vision): The rods are repsonsible for night and peripheral vision (< 0.001 cd/m2). Mesopic (Dim Light Vision): occurs when the light levels are low but one can still see color (between 0.001 and 3 cd/m2). 3 VisibleRange Daylighting Hanbook (Reinhart) The human eye can see across twelve orders of magnitude. We can adapt to about 10 orders of magnitude at a time via the iris. Larger ranges take time and require ‘neural adaptation’. Transition Spaces Outside Atrium Circulation Area Final destination 4 Luminous Response Curve of the Human Eye What is daylight? Daylight is the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum that lies between 380 and 780 nm. UV blue green yellow orange red IR 380 450 500 550 600 650 700 750 wave length (nm) 5 Photometric Quantities Characterize how a space is perceived. Illuminance Luminous Flux Luminance Luminous Intensity Luminous Intensity [Candela] ~ 1 candela Courtesy of Matthew Bowden at www.digitallyrefreshing.com. -

Illumination and Distance

PHYS 1400: Physical Science Laboratory Manual ILLUMINATION AND DISTANCE INTRODUCTION How bright is that light? You know, from experience, that a 100W light bulb is brighter than a 60W bulb. The wattage measures the energy used by the bulb, which depends on the bulb, not on where the person observing it is located. But you also know that how bright the light looks does depend on how far away it is. That 100W bulb is still emitting the same amount of energy every second, but if you are farther away from it, the energy is spread out over a greater area. You receive less energy, and perceive the light as less bright. But because the light energy is spread out over an area, it’s not a linear relationship. When you double the distance, the energy is spread out over four times as much area. If you triple the distance, the area is nine Twice the distance, ¼ as bright. Triple the distance? 11% as bright. times as great, meaning that you receive only 1/9 (or 11%) as much energy from the light source. To quantify the amount of light, we will use units called lux. The idea is simple: energy emitted per second (Watts), spread out over an area (square meters). However, a lux is not a W/m2! A lux is a lumen per m2. So, what is a lumen? Technically, it’s one candela emitted uniformly across a solid angle of 1 steradian. That’s not helping, is it? Examine the figure above. The source emits light (energy) in all directions simultaneously. -

2.1 Definition of the SI

CCPR/16-53 Modifications to the Draft of the ninth SI Brochure dated 16 September 2016 recommended by the CCPR to the CCU via the CCPR president Takashi Usuda, Wednesday 14 December 2016. The text in black is a selection of paragraphs from the brochure with the section title for indication. The sentences to be modified appear in red. 2.1 Definition of the SI Like for any value of a quantity, the value of a fundamental constant can be expressed as the product of a number and a unit as Q = {Q} [Q]. The definitions below specify the exact numerical value of each constant when its value is expressed in the corresponding SI unit. By fixing the exact numerical value the unit becomes defined, since the product of the numerical value {Q} and the unit [Q] has to equal the value Q of the constant, which is postulated to be invariant. The seven constants are chosen in such a way that any unit of the SI can be written either through a defining constant itself or through products or ratios of defining constants. The International System of Units, the SI, is the system of units in which the unperturbed ground state hyperfine splitting frequency of the caesium 133 atom Cs is 9 192 631 770 Hz, the speed of light in vacuum c is 299 792 458 m/s, the Planck constant h is 6.626 070 040 ×1034 J s, the elementary charge e is 1.602 176 620 8 ×1019 C, the Boltzmann constant k is 1.380 648 52 ×1023 J/K, 23 -1 the Avogadro constant NA is 6.022 140 857 ×10 mol , 12 the luminous efficacy of monochromatic radiation of frequency 540 ×10 hertz Kcd is 683 lm/W. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Exposure Metering and Zone System Calibration

Exposure Metering Relating Subject Lighting to Film Exposure By Jeff Conrad A photographic exposure meter measures subject lighting and indicates camera settings that nominally result in the best exposure of the film. The meter calibration establishes the relationship between subject lighting and those camera settings; the photographer’s skill and metering technique determine whether the camera settings ultimately produce a satisfactory image. Historically, the “best” exposure was determined subjectively by examining many photographs of different types of scenes with different lighting levels. Common practice was to use wide-angle averaging reflected-light meters, and it was found that setting the calibration to render the average of scene luminance as a medium tone resulted in the “best” exposure for many situations. Current calibration standards continue that practice, although wide-angle average metering largely has given way to other metering tech- niques. In most cases, an incident-light meter will cause a medium tone to be rendered as a medium tone, and a reflected-light meter will cause whatever is metered to be rendered as a medium tone. What constitutes a “medium tone” depends on many factors, including film processing, image postprocessing, and, when appropriate, the printing process. More often than not, a “medium tone” will not exactly match the original medium tone in the subject. In many cases, an exact match isn’t necessary—unless the original subject is available for direct comparison, the viewer of the image will be none the wiser. It’s often stated that meters are “calibrated to an 18% reflectance,” usually without much thought given to what the statement means. -

Recommended Light Levels

Recommended Light Levels Recommended Light Levels (Illuminance) for Outdoor and Indoor Venues This is an instructor resource with information to be provided to students as the instructor sees fit. Light Level or Illuminance, is the amount of light measured in a plane surface (or the total luminous flux incident on a surface, per unit area). The work plane is where the most important tasks in the room or space are performed. Measuring Units of Light Level - Illuminance Illuminance is measured in foot candles (ftcd, fc, fcd) or lux (in the metric SI system). A foot candle is actually one lumen of light density per square foot; one lux is one lumen per square meter. • 1 lux = 1 lumen / sq meter = 0.0001 phot = 0.0929 foot candle (ftcd, fcd) • 1 phot = 1 lumen / sq centimeter = 10000 lumens / sq meter = 10000 lux • 1 foot candle (ftcd, fcd) = 1 lumen / sq ft = 10.752 lux Common Light Levels Outdoors from Natural Sources Common light levels outdoor at day and night can be found in the table below: Illumination Condition (ftcd) (lux) Sunlight 10,000 107,527 Full Daylight 1,000 10,752 Overcast Day 100 1,075 Very Dark Day 10 107 Twilight 1 10.8 Deep Twilight .1 1.08 Full Moon .01 .108 Quarter Moon .001 .0108 Starlight .0001 .0011 Overcast Night .00001 .0001 Common Light Levels Outdoors from Manufactured Sources The nomenclature for most of the types of areas listed in the table below can be found in the City of Los Angeles, Department of Public Works, Bureau of Street Lighting’s “DESIGN STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES” at the URL address under References at the end of this document. -

Spectral Light Measuring

Spectral Light Measuring 1 Precision GOSSEN Foto- und Lichtmesstechnik – Your Guarantee for Precision and Quality GOSSEN Foto- und Lichtmesstechnik is specialized in the measurement of light, and has decades of experience in its chosen field. Continuous innovation is the answer to rapidly changing technologies, regulations and markets. Outstanding product quality is assured by means of a certified quality management system in accordance with ISO 9001. LED – Light of the Future The GOSSEN Light Lab LED technology has experience rapid growth in recent years thanks to the offers calibration services, for our own products, as well as for products from development of LEDs with very high light efficiency. This is being pushed by other manufacturers, and issues factory calibration certificates. The optical the ban on conventional light bulbs with low energy efficiency, as well as an table used for this purpose is subject to strict test equipment monitoring, and ever increasing energy-saving mentality and environmental awareness. LEDs is traced back to the PTB in Braunschweig, Germany (German Federal Institute have long since gone beyond their previous status as effects lighting and are of Physics and Metrology). Aside from the PTB, our lab is the first in Germany being used for display illumination, LED displays and lamps. Modern means to be accredited for illuminance by DAkkS (German accreditation authority), of transportation, signal systems and street lights, as well as indoor and and is thus authorized to issue internationally recognized DAkkS calibration outdoor lighting, are no longer conceivable without them. The brightness and certificates. This assures that acquired measured values comply with official color of LEDs vary due to manufacturing processes, for which reason they regulations and, as a rule, stand up to legal argumentation. -

Photometric Calibrations —————————————————————————

NIST Special Publication 250-37 NIST MEASUREMENT SERVICES: PHOTOMETRIC CALIBRATIONS ————————————————————————— Yoshihiro Ohno Optical Technology Division Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Supersedes SP250-15 Reprint with changes July 1997 ————————————————————————— U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE William M. Daley, Secretary Technology Administration Gary R. Bachula, Acting Under Secretary for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology Robert E. Hebner, Acting Director PREFACE The calibration and related measurement services of the National Institute of Standards and Technology are intended to assist the makers and users of precision measuring instruments in achieving the highest possible levels of accuracy, quality, and productivity. NIST offers over 300 different calibrations, special tests, and measurement assurance services. These services allow customers to directly link their measurement systems to measurement systems and standards maintained by NIST. These services are offered to the public and private organizations alike. They are described in NIST Special Publication (SP) 250, NIST Calibration Services Users Guide. The Users Guide is supplemented by a number of Special Publications (designated as the “SP250 Series”) that provide detailed descriptions of the important features of specific NIST calibration services. These documents provide a description of the: (1) specifications for the services; (2) design philosophy and theory; (3) NIST measurement system; (4) NIST operational procedures; (5) assessment of the measurement uncertainty including random and systematic errors and an error budget; and (6) internal quality control procedures used by NIST. These documents will present more detail than can be given in NIST calibration reports, or than is generally allowed in articles in scientific journals. In the past, NIST has published such information in a variety of ways. -

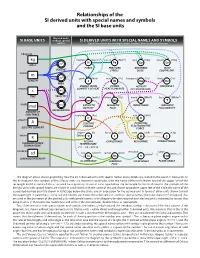

Relationships of the SI Derived Units with Special Names and Symbols and the SI Base Units

Relationships of the SI derived units with special names and symbols and the SI base units Derived units SI BASE UNITS without special SI DERIVED UNITS WITH SPECIAL NAMES AND SYMBOLS names Solid lines indicate multiplication, broken lines indicate division kilogram kg newton (kg·m/s2) pascal (N/m2) gray (J/kg) sievert (J/kg) 3 N Pa Gy Sv MASS m FORCE PRESSURE, ABSORBED DOSE VOLUME STRESS DOSE EQUIVALENT meter m 2 m joule (N·m) watt (J/s) becquerel (1/s) hertz (1/s) LENGTH J W Bq Hz AREA ENERGY, WORK, POWER, ACTIVITY FREQUENCY second QUANTITY OF HEAT HEAT FLOW RATE (OF A RADIONUCLIDE) s m/s TIME VELOCITY katal (mol/s) weber (V·s) henry (Wb/A) tesla (Wb/m2) kat Wb H T 2 mole m/s CATALYTIC MAGNETIC INDUCTANCE MAGNETIC mol ACTIVITY FLUX FLUX DENSITY ACCELERATION AMOUNT OF SUBSTANCE coulomb (A·s) volt (W/A) C V ampere A ELECTRIC POTENTIAL, CHARGE ELECTROMOTIVE ELECTRIC CURRENT FORCE degree (K) farad (C/V) ohm (V/A) siemens (1/W) kelvin Celsius °C F W S K CELSIUS CAPACITANCE RESISTANCE CONDUCTANCE THERMODYNAMIC TEMPERATURE TEMPERATURE t/°C = T /K – 273.15 candela 2 steradian radian cd lux (lm/m ) lumen (cd·sr) 2 2 (m/m = 1) lx lm sr (m /m = 1) rad LUMINOUS INTENSITY ILLUMINANCE LUMINOUS SOLID ANGLE PLANE ANGLE FLUX The diagram above shows graphically how the 22 SI derived units with special names and symbols are related to the seven SI base units. In the first column, the symbols of the SI base units are shown in rectangles, with the name of the unit shown toward the upper left of the rectangle and the name of the associated base quantity shown in italic type below the rectangle. -

International System of Units (SI)

International System of Units (SI) National Institute of Standards and Technology (www.nist.gov) Multiplication Prefix Symbol factor 1018 exa E 1015 peta P 1012 tera T 109 giga G 106 mega M 103 kilo k 102 * hecto h 101 * deka da 10-1 * deci d 10-2 * centi c 10-3 milli m 10-6 micro µ 10-9 nano n 10-12 pico p 10-15 femto f 10-18 atto a * Prefixes of 100, 10, 0.1, and 0.01 are not formal SI units From: Downs, R.J. 1988. HortScience 23:881-812. International System of Units (SI) Seven basic SI units Physical quantity Unit Symbol Length meter m Mass kilogram kg Time second s Electrical current ampere A Thermodynamic temperature kelvin K Amount of substance mole mol Luminous intensity candela cd Supplementary SI units Physical quantity Unit Symbol Plane angle radian rad Solid angle steradian sr From: Downs, R.J. 1988. HortScience 23:881-812. International System of Units (SI) Derived SI units with special names Physical quantity Unit Symbol Derivation Absorbed dose gray Gy J kg-1 Capacitance farad F A s V-1 Conductance siemens S A V-1 Disintegration rate becquerel Bq l s-1 Electrical charge coulomb C A s Electrical potential volt V W A-1 Energy joule J N m Force newton N kg m s-2 Illumination lux lx lm m-2 Inductance henry H V s A-1 Luminous flux lumen lm cd sr Magnetic flux weber Wb V s Magnetic flux density tesla T Wb m-2 Pressure pascal Pa N m-2 Power watt W J s-1 Resistance ohm Ω V A-1 Volume liter L dm3 From: Downs, R.J. -

Light Measurement Handbook from an Oblique Angle, It Should Look As Bright As It Did When Held Perpendicular to Your Line of Vision

Alex Ryer RED Boxes - LINKS to Current Info on Web Site Peabody, MA (USA) To receive International Light's latest Light Measurement Instruments Catalog, contact: InternationalInternational Light Technologies Light 10 Technology Drive Peabody,10 Te11 MA17 01960 Graf Road Tel:New (978) 818-6180 / buryport,Fax: (978) 818-8161 MA 01950 [email protected] / www.intl-lighttech.com Tel: (978) 465-5923 • Fax: (978) 462-0759 [email protected] • http://www.intl-light.com Copyright © 1997 by Alexander D. Ryer All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests should be made through the publisher. Technical Publications Dept. International Light Technologies 10 Technology Drive Peabody, MA 01960 ISBN 0-9658356-9-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97-93677 Second Printing Printed in the United States of America. 2 Contents 1 What is Light? ........................................................... 5 Electromagnetic Wave Theory........................................... 5 Ultraviolet Light ................................................................. 6 Visible Light ........................................................................ 7 Color Models ....................................................................... 7 Infrared Light ..................................................................... -

The International System of Units (SI)

NAT'L INST. OF STAND & TECH NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology Technology Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce NIST Special Publication 330 2001 Edition The International System of Units (SI) 4. Barry N. Taylor, Editor r A o o L57 330 2oOI rhe National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303.