New-School Trademark Dilution: Famous Among the Juvenile Consuming Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kohl's Department Stores Offers the Best the Gifts at the Best Values to Help Shoppers Get the Most for Their Money This Holid

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Desta Davis Senior Manager, Public Relations Ph: 262-703-3854 Email: [email protected] Karlyn Nelson/Nick Jones MPRM Communications on behalf of AwesomenessTV Ph: 323-933-3399 Email: [email protected] Kohl’s Department Stores Partners with AwesomenessTV on Breakthrough New Fashion Line and Original YouTube Series Limited-edition junior’s capsule collection launches exclusively at Kohl’s beginning fall 2014 MENOMONEE FALLS, Wis., September 3, 2014 – Kohl’s Department Stores (NYSE: KSS) and AwesomenessTV today announced a partnership to launch S.o. R.a.d., a seven capsule limited-edition junior’s fashion line and Life’s S.o. R.a.d., an original four season YouTube series featuring top teen influencers. The first S.o. R.a.d. junior’s capsule will launch at Kohl’s and Kohls.com on September 22, 2014. "We partnered with Kohl's because we shared a vision for revolutionizing the typical approach to consumer products," said James D. Fielding, Global Head of Consumer Products and Retail at AwesomenessTV. "Kohl's is also where our audience shops, making them the perfect fit for the S.o. R.a.d. brand." “We are thrilled to partner with a cutting-edge company like AwesomenessTV and leverage the power of their new frontier of YouTube influencers to bring amazing product to our junior’s shoppers,” said Will Setliff, Executive Vice President of Marketing at Kohl’s. “We recognize the growing value of digital content creation and social media consumption, and are confident this new platform will create genuine, organic conversation among our teen demographic.” The first S.o. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

MARCUS ALEXANDER Stereographer/Stereo Producer/Stereo Supervisor

MARCUS ALEXANDER Stereographer/Stereo Producer/Stereo Supervisor PROJECTS DIRECTOR STUDIO & PRODUCERS “WARCRAFT” DUNCAN JONES ATLAS ENTERTAINMENT Stereo Consultant LEGENDARY PICTURES Alex Gartner, Jon Jashni, Charles Roven, Thomas Tull “GODZILLA” GARETH EDWARDS WARNER BROS. PICTURES Stereo Consultant LEGENDARY PICTURES Jon Jashni, Mary Parent, Brian Rogers, Thomas Tull LEGENDARY PICTURES LOGO EMILY CASTEL LEGENDARY PICTURES Stereo Consultant TRAILER PARK Jake Rice “THE SEVENTH SON” SERGEI BODROV LEGENDARY PICTURES Stereographic Supervisor Basil Iwanyk, Thomas Tull, Lionel Wigram “WRATH OF THE TITANS” JONATHAN LIEBESMAN WARNER BROS. PICTURES Post Stereographer/Stereo Producer Basil Iwanyk, Polly Johnsen Film nominated for I3DS Callum McDougall (Best Post Supervision 2D to 3D) “STAR WARS: EPISODE I – GEORGE LUCAS TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX THE PHANTOM MENACE 3D” LUCASFILM Stereo Producer (Prime Focus) Rick McCallum + Stereography Support - UC “THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA:THE MICHAEL APTED TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX VOYAGE OF THE DAWN TREADER” WALDEN MEDIA Stereoscopic Support Andrew Adamson, Mark Johnson, (Prime Focus) Philip Steuer “DEAD CRAZY” FRANK SCANTORI THE FILM THEATRE COMPANY Cinematographer “YELLING TO THE SKY” VICTORIA MAHONEY ELEPHANT EYE FILMS Digital Intermediate Producer (Deluxe NYC) “LAST NIGHT” MASSY TADJEDIN GAUMONT/NICK WECHSLER PRODS. D. I. Manager (Deluxe New York) "SHANGHAI" MIKAEL HAFSTROM PHOENIX PICTURES Digital Intermediate Manager (Deluxe NYC) “LETTERS TO JULIETTE” GARY WINICK SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT Digital Intermediate Manager (Deluxe NYC) "THE BOUNTY HUNTER" ANDY TENNANT COLUMBIA PICTURES D. I. Manager (UC) (Deluxe New York) Marcus Alexander -Continued- "REMEMBER ME" ALLEN COULTER SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT D. I. Manager (Deluxe New York) "GREENBERG" NOAH BAUMBACH FOCUS FEATURES Digital Intermediate Producer (EFILM) "THE LAST SURVIVOR" (Documentary) MICHAEL KLEIMAN RIGHTEOUS PICTURES D.I. -

Kellogg Company 2012 Annual Report

® Kellogg Company 2012 Annual Report ™ Pringles Rice Krispies Kashi Cheez-It Club Frosted Mini Wheats Mother’s Krave Keebler Corn Pops Pop Tarts Special K Town House Eggo Carr’s Frosted Flakes All-Bran Fudge Stripes Crunchy Nut Chips Deluxe Fiber Plus Be Natural Mini Max Zucaritas Froot Loops Tresor MorningStar Farms Sultana Bran Pop Tarts Corn Flakes Raisin Bran Apple Jacks Gardenburger Famous Amos Pringles Rice Krispies Kashi Cheez-It Club Frosted Mini Wheats Mother’s Krave Keebler Corn Pops Pop Tarts Special K Town House Eggo Carr’s Frosted Flakes All-Bran Fudge Stripes Crunchy Nut Chips Deluxe Fiber Plus Be Natural Mini Max Zucaritas Froot Loops Tresor MorningStar Farms Sultana Bran Pop Tarts Corn Flakes Raisin Bran Apple JacksCONTENTS Gardenburger Famous Amos Pringles Rice Letter to Shareowners 01 KrispiesOur Strategy Kashi Cheez-It03 Club Frosted Mini Wheats Pringles 04 Our People 06 Mother’sOur Innovations Krave Keebler11 Corn Pops Pop Tarts Financial Highlights 12 Our Brands 14 SpecialLeadership K Town House15 Eggo Carr’s Frosted Flakes Financials/Form 10-K All-BranBrands and Trademarks Fudge Stripes01 Crunchy Nut Chips Deluxe Selected Financial Data 14 FiberManagement’s Plus Discussion Be & Analysis Natural 15 Mini Max Zucaritas Froot Financial Statements 30 Notes to Financial Statements 35 LoopsShareowner Tresor Information MorningStar Farms Sultana Bran Pop Tarts Corn Flakes Raisin Bran Apple Jacks Gardenburger Famous Amos Pringles Rice Krispies Kashi Cheez-It Club Frosted Mini Wheats Mother’s Krave Keebler Corn Pops Pop Tarts Special K Town House Eggo Carr’s Frosted Flakes All-Bran Fudge Stripes Crunchy Nut Chips Deluxe Fiber Plus2 Be NaturalKellogg Company 2012 Annual Mini Report MaxMOVING FORWARD. -

Ciné Récré Des Films Pour Les Enfants Dans Les Cinémas De Nice

CINÉ RÉCRÉ DES FILMS POUR LES ENFANTS DANS LES CINÉMAS DE NICE 9 - 10 - 16 - 17 NOVEMBRE 2019 CINÉMATHÈQUE - MERCURY - RIALTO - VARIÉTÉS PATHÉ LINGOSTIÈRE - PATHÉ MASSÉNA - PATHÉ GARE DU SUD LES AVANT-PREMIÈRES Le Cristal magique Dès 3 ans Sortie le 11 décembre 2019 de Nina Wels et Regina Welker / 2019/ Animation / Allemagne /1h21 Bantour, le roi des ours, a volé le cristal magique qui permet de faire revenir l’eau dans la forêt. Amy la petite hérissonne et son ami Tom l’écureuil décident de partir à sa recherche… Samedi 16 novembre à 13h40/ Dimanche 17 novembre à 15h40 RIALTO La Famille Addams Dès 6 ans Sortie le 4 décembre 2019 de Conrad Vernon et Greg Tiernan / 2019 / Animation / USA /1h27 Les nouvelles aventures étranges, drôles et mobides de la Famille Addams. Dimanche 17 novembre à 16h45 PATHÉ LINGOSTIÈRE / PATHÉ MASSÉNA / PATHÉ GARE DU SUD Mission Yéti Dès 3 ans Sortie le 29 janvier 2020 de Pierre Gréco et Nancy Florence Savard / 2017 / Animation / Canada / 1h20 Nelly, détective privée, et Simon, assistant de recherche, partent à l’aventure au cœur de l’Himalaya à la rencontre du Yéti. Samedi 9 novembre à 13h40 / Dimanche 10 novembre à 15h40 Samedi 16 novembre à 15h40 / Dimanche 17 novembre à 13h40 VARIÉTÉS SamSam Dès 3 ans Sortie le 5 février 2020 de Tanguy de Kermel / 2019/ Animation / France, Belgique. SamSam, le plus petit des grands héros, part à la recherche son premier super pouvoir… Avec l’aide de Méga, la nouvelle élève mystérieuse de son école, il se lance dans une aventure pleine de monstres cosmiques. -

ASUI Board Chair Spends Unauthorized Funds Mike Mcnulty the Student Elections

lVews. ~ Sports ~ DIVERSIONS - UI graduate student German tandem defines :. receives outstanding running success for the 4'+r, ro. 'o '; student award. VIIndah. 9p c~ O~ See page 4. See page 11. r+ ~r ,t(;f)(l!ls .r<'r tltIjj THE UNIVERSITY DF IDAHQ Frida, Se tember 8, 1995 ASUI —Moscow, Idaho Volume 971V0. S Stop the smoke ASUI Board Chair spends unauthorized funds Mike McNulty the student elections. The money for comment. Staff comes primarily from student fees ASUI Senator Clint Cook, who which supports ASUI's near $1 mil- resigned from office last week, said t was a flagrant misuse of lion annual budget. he was at the dinner which was a the students'noney," ASUI ASUI Senator Christs Manis said "reward" for board members who put President Wilson said Sean "it's a shame" the student legislature in over 20 hours of unpaid work dur- about a chairperson's decision to is often slowed down by minor ing the spring election. He said spend an unauthorized amount of details. Shaltry was just appointed to her cash on an dinner last expensive "We'e just tired of knit-picking," position and was unfamiliar with cer- semester. said Manis. "It's hard to keep things tain procedures. Angie Shaltry, chairperson for the moving when we have to deal with "No one told her the rules," said Student Issues Board, was authorized this.'" things like Cook. "Angie thought the money was to buy dinner for board members after President Wilson said he found out available to be spent." the spring election with a UI depart- stu- about the dinner party after most Cook said everything was "straight- mental purchase order issued by vacation dents had left for summer ened out" and the situation has been ASUI Business Adviser Sandra Gray. -

Kellogg Company September 6, 2017

Kellogg Company September 6, 2017 Kellogg Company Barclays Global Consumer Staples Conference Boston September 6, 2017 Forward-Looking Statements This presentation contains, or incorporates by reference, “forward-looking statements” with projections concerning, among other things, the Company’s global growth and efficiency program (Project K), the integration of acquired businesses, the Company’s strategy, zero-based budgeting, and the Company’s sales, earnings, margin, operating profit, costs and expenditures, interest expense, tax rate, capital expenditure, dividends, cash flow, debt reduction, share repurchases, costs, charges, rates of return, brand building, ROIC, working capital, growth, new products, innovation, cost reduction projects, workforce reductions, savings, and competitive pressures. Forward-looking statements include predictions of future results or activities and may contain the words “expects,” “believes,” “should,” “will,” “anticipates,” “projects,” “estimates,” “implies,” “can,” or words or phrases of similar meaning. The Company’s actual results or activities may differ materially from these predictions. The Company’s future results could also be affected by a variety of factors, including the ability to implement Project K (including the exit from its Direct Story Delivery system) as planned, whether the expected amount of costs associated with Project K will differ from forecasts, whether the Company will be able to realize the anticipated benefits from Project K in the amounts and times expected, the ability to -

Peanut-Free Snacks

Peanut/Tree Nut-Free Snacks Below you will find a list of many snacks that are peanut/tree nut-free at this time. It is always important to read the ingredient labels since manufacturers change production methods. Cereal/Bars General Mills Cinnamon Toast Crunch Kix, Berry Berry Kix Lucky Charms Rice Chex, Corn Chex, Wheat Chex Trix Kellogg's Cereals - Corn Pops, Crispix, Fruit Loops, Post Alpha Bits, Quaker Cap 'N Crunch Nutri-Grain - Apple, Blueberry, Raspberry Nutri-Grain Twist - Banana & Strawberry, Strawberries & Cream Pop Tarts (apple, strawberry, blueberry) Post Honey Combs Cheese/Dairy Sargento Mootown Snacks - Cheeze & Pretzels, Cheeze & Crackers, Cheeze & Sticks Yogurt Go-Gurt, Drinkables, any other yogurt without nuts/tree nuts Other Cheeses Sliced, cubed, shredded, string cheese, cream cheese, spreads, dips Crackers/Chips/Cookies Austin Zoo Animal Crackers Betty Crocker Cinnamon Graham Cookies Dunk Aroos Frito Lay Cheetos - Crunch, Zigzag, Puffs Rold Gold Pretzels Sun Chips - Original, Sour Cream, Cheddar, Classic, Flavored General Mills Bugles - Original Keebler Bite Size Snackin Grahams - Cinnamon, Chocolate Butter Cookies Grasshopper Cookies Elf Grahams - Honey, Cinnamon Fudge Stripes Shortbread Cookies Golden Vanilla Wafers Grasshopper Mint Cookies New Rainbow Vanilla Wafers Munch'ems - Sour Cream & Onion, Original, Ranch, Cheddar Snack Stix Sugar Wafers Toasteds - Wheat, Buttercrisp Town House Classic Crackers Wheatables - Original, Honey Wheat, Seven Grain Kraft Handi-Snacks - Cheez 'N Crackers, Apple Dippers, Cheez 'N -

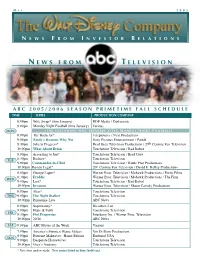

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

2017 Super Skus

® 2017 Super SKUs 1 2 3 4 5 Rice Krispies Treats® Cheez-It® Baked Pop-Tarts® Pringles® Original Special K® Big Bar Original Snack Crackers Frosted Strawberry Large Grab & Go Protein Meal Bar 12 / 2.20 oz. Original 6 / 3.67 oz. 12 / 2.36 oz. Strawberry 6 / 3.00 oz. 8 / 1.59 oz. 6 7 8 9 10 Pringles® Pringles® Pringles® Special K® Nutri-Grain® Sour Cream & Onion Original Sour Cream & Onion Protein Meal Bar Cereal Bar Standard Can Standard Can Large Grab & Go Chocolate Peanut Butter Strawberry 14 / 5.57 oz. 14 / 5.26 oz. 12 / 2.50 oz. 8 / 1.59 oz. 16 / 1.30 oz. 11 12 13 14 15 Keebler® Keebler® Rice Krispies Treats® Pop-Tarts® Pringles® Cheddar Sandwich Crackers Sandwich Crackers Original Frosted Brown Large Grab & Go Toast & Peanut Butter Cheese & Peanut Butter 20 / 1.30 oz. Sugar Cinnamon 12 / 2.50 oz. 12 / 1.80 oz. 12 / 1.80 oz. 6 / 3.52 oz. 16 17 18 19 20 Cheez-It® Baked Famous Amos® Keebler® Keebler® Keebler® Soft Batch® Snack Crackers Chocolate Chip Club® & Cheddar Sugar Wafers Chocolate Chip Cookies White Cheddar 6 / 3.00 oz. Sandwich Crackers Vanilla 12 / 2.20 oz. 6 / 3.00 oz. 12 / 1.80 oz. 12 / 2.75 oz. 81425 ® 2017 Super SKUs 21 22 23 24 25 Cheez-It Duoz® Pringles® BBQ Pringles® Cheddar Pringles® BBQ Pop-Tarts® Sharp Cheddar / Parmesan Large Grab & Go® Standard Can Standard Can Frosted S’mores 6 / 4.30 oz. 12 / 2.50 oz. 14 / 5.57 oz. 14 / 5.57 oz. -

A Conversation with Mark Salter, Author of “The

A Conversation with Mark Salter, Author of “The Luckiest Man: Life with John McCain” Join Michael Zeldin in his conversation with Mark Salter, Author of The Luckiest Man: Life with John McCain. Salter collaborated with John McCain on all seven of their books, including The Restless Wave, Faith of My Fathers, Worth the Fighting For, Why Courage Matters, Character Is Destiny, Hard Call, and Thirteen Soldiers. He served on Senator McCain’s staff for eighteen years. Guest Mark Salter Author of “The Luckiest Man: Life with John McCain” Mark Salter is an American speechwriter from Davenport, Iowa, known for his collaborations with United States Senator John McCain on several nonfiction books as well as on political speeches. Salter also served as McCain’s chief of staff for a while, although he had left that position by 2008. About the Book More so than almost anyone outside of McCain’s immediate family, Mark Salter had unparalleled access to and served to influence the Senator’s thoughts and actions, cowriting seven books with him and acting as a valued confidant. Now, in The Luckiest Man, Salter draws on the storied facets of McCain’s early biography as well as the later-in-life political philosophy for which the nation knew and loved him, delivering an intimate and comprehensive account of McCain’s life and philosophy. Salter covers all the major events of McCain’s life—his peripatetic childhood, his naval service—but introduces, too, aspects of the man that the public rarely saw and hardly knew. Woven throughout this narrative is also the story of Salter and McCain’s close relationship, including how they met, and why their friendship stood the test of time in a political world known for its fickle personalities and frail bonds.