DOMESTIC ASSET PROTECTION TRUST STATUTES Updated Through August 2019 Edited by David G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

Azar V. Azar, 146 N.W.2D 148 (N.D

N.D. Supreme Court Azar v. Azar, 146 N.W.2d 148 (N.D. 1966) Filed Nov. 4, 1966 [Go to Documents] IN THE SUPREME COURT STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA James J. Azar, Plaintiff and Respondent, v. Betty Azar, Defendant and Appellant. Case No. 8257 [146 N.W.2d 149] Syllabus of the Court 1. Extreme cruelty as a ground for divorce is an infliction of grievous bodily injury or grievous mental suffering. Section 14-05-05, N.D.C.C. 2. Whether one party to a divorce action has inflicted grievous mental suffering upon the other is a question of fact to be determined from all the circumstances in the case. 3. Upon a trial de novo on appeal, the findings of fact of the trial judge are entitled to appreciable weight. 4. When a divorce is granted, the trial court has continuing jurisdiction with regard to the custody, care, education, and welfare of the minor children of the marriage. Section 14-05-22, N.D.C.C. 5. In the matter of awarding custody of the children of the parties to an action for divorce, the trial court is vested with a large discretion, and its discretion will ordinarily not be interfered with except for an abuse thereof. 6. In a divorce proceeding the court shall make such equitable distribution of the real and personal property of the parties as may seem just and proper. Section 14-05-24, N.D.C.C. Appeal from a judgment of the District Court of Burleigh County, Honorable C. F. Kelsch, Special Judge. -

Uniform Trust Code

D R A F T FOR DISCUSSION ONLY UNIFORM TRUST CODE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS MARCH 10, 2000 INTERIM DRAFT UNIFORM TRUST CODE WITHOUT PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright © 2000 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS The ideas and conclusions set forth in this draft, including the proposed statutory language and any comments or reporter’s notes, have not been passed upon by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws or the Drafting Committee. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Conference and its Commissioners and the Drafting Committee and its Members and Reporters. Proposed statutory language may not be used to ascertain the intent or meaning of any promulgated final statutory proposal. UNIFORM TRUST CODE TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS AND DEFINITIONS SECTION 101. SHORT TITLE. ............................................................ 1 SECTION 102. SCOPE. ................................................................... 1 SECTION 103. DEFINITIONS. ............................................................. 1 SECTION 104. DEFAULT AND MANDATORY RULES. ...................................... 4 SECTION 105. QUALIFIED BENEFICIARIES. ............................................... 5 SECTION 106. NOTICE. .................................................................. 5 SECTION 107. COMMON LAW OF TRUSTS. ................................................ 6 SECTION 108. CHOICE OF LAW. ......................................................... -

Will the Alaska Trusts Work? Leslie C

JOURNAL OF ASSET PROTECTION September / October 1997 Will the Alaska Trusts Work? Leslie C. Giordani and Duncan E. Osborne Those contemplating establishing an Alaska asset protection trust based on that state’s new statute should first consider the impediments to effective asset protection in Alaska, both those intrinsic to Alaska’s statehood and those in the new Alaska law. mandate in the Constitution,1 Alaska courts hen a prospective settlor of an must recognize judgments rendered under Wasset protection trust evaluates the laws of less debtor-friendly states. In various jurisdictions to determine addition, the enactment of laws enabling the best location for the trust, one asset protection trusts may itself violate the consideration is paramount: the level of Constitution’s contract clause.2 Finally, due shelter from creditors’ claims. Issues such as to the supremacy clause3 of the Constitution, physical proximity, cultural comfort, and the Alaska statute cannot protect debtors familiarity with the local legal system from conflicting federal law (in this case, become important only after the desired bankruptcy law). Even if the legislation level of protection is reached. Thus, the passes constitutional muster, however, it settlor (or the settlor’s advisor) must focus does not necessarily protect an asset on the legal tools a creditor can use to attack protection trust from some of the arguments a trust and must determine the available to a creditor through existing corresponding defenses each jurisdiction Alaska law. provides. The most successful asset The new statute, existing statutory protection jurisdictions have erected legal provisions, and Alaska common law provide barriers that all but eliminate the creditor’s various opportunities for a sympathetic arsenal. -

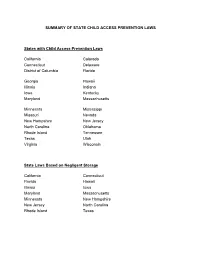

Summary of State Child Access Prevention Laws

SUMMARY OF STATE CHILD ACCESS PREVENTION LAWS States with Child Access Prevention Laws California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Illinois Indiana Iowa Kentucky Maryland Massachusetts Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey North Carolina Oklahoma Rhode Island Tennessee Texas Utah Virginia Wisconsin State Laws Based on Negligent Storage California Connecticut Florida Hawaii Illinois Iowa Maryland Massachusetts Minnesota New Hampshire New Jersey North Carolina Rhode Island Texas States Imposing Criminal Liability for Allowing a Child to Gain Access to the Firearm, Regardless of Whether the Child Uses the Firearm or Causes Injury Hawaii Maryland Massachusetts Minnesota New Jersey Texas States Imposing Criminal Liability Only if a Child Uses or Possesses the Firearm California Connecticut Florida Illinois Iowa New Hampshire North Carolina Rhode Island States Imposing Criminal Liability for Negligent Storage of Unloaded Firearms California Hawaii Massachusetts State Laws Prohibiting Intentional, Knowing or Reckless Provision of Firearms to Minors Colorado Delaware Georgia Indiana Kentucky Mississippi Missouri Nevada Oklahoma Tennessee Utah Virginia Wisconsin Description of State Child Access Prevention Laws The majority of states have laws designed to prevent children from accessing firearms. The strongest laws impose criminal liability when a minor gains access to a negligently stored firearm. The weakest prohibit persons from directly providing a firearm to a minor. There is a wide range of laws that fall somewhere between these extremes, including laws that impose criminal liability for negligently stored firearms, but only where the child uses the firearm and causes death or serious injury. Weaker laws impose liability only in the event of reckless, knowing or intentional conduct by the adult. -

Special Needs Trust Comment: This Is an Irrevocable Inter Vivos Trust for the Benefit of the Settlor's Disabled Child. It Is

Special Needs Trust Comment: This is an irrevocable inter vivos trust for the benefit of the settlor's disabled child. It is designed to provide the maximum benefits to the child without threatening eligibility for Medicaid or other public programs. This Form assumes immediate funding of the trust. THE ______________________ [Name of Beneficiary] IRREVOCABLE TRUST ARTICLE I. AGREEMENT This Trust Agreement is made this ________ [date] ________ day of ________ [month, year], by ________ [Name of Settlor], of ________ [address], as Settlor, and ________ [Name of Trustee] of ________ [address], as Trustee. This is an irrevocable trust for the benefit of Settlor's ________ [indicate relationship], of ________ [address]. Settlor declares that ________ [he/she] has transferred to the Trustee, without consideration, the property described in Schedule A attached to this instrument. The Trustee hereby agrees to hold that property and any other property of the trust estate, in trust, on the terms set forth in this instrument. It is Settlor's desire, by this instrument, to create an inter vivos irrevocable trust, in accordance with the laws of the State of ________ [indicate State], whereby the property placed in trust shall be managed for the benefit of ________ [Name of Beneficiary] during ________ [his/her] lifetime and distributed to the beneficiary named herein upon the death of ________ [Name of Beneficiary]. ARTICLE II. INTRODUCTION The intent of this Trust is to supplement any benefits received (or for which ________ [Name of Beneficiary] may be eligible) through or from various governmental assistance programs and not to supplant any such benefits. -

List of Surrounding States *For Those Chapters That Are Made up of More Than One State We Will Submit Education to the States and Surround States of the Chapter

List of Surrounding States *For those Chapters that are made up of more than one state we will submit education to the states and surround states of the Chapter. Hawaii accepts credit for education if approved in state in which class is being held Accepts credit for education if approved in state in which class is being held Virginia will accept Continuing Education hours without prior approval. All Qualifying Education must be approved by them. Offering In Will submit to Alaska Alabama Florida Georgia Mississippi South Carolina Texas Arkansas Kansas Louisiana Missouri Mississippi Oklahoma Tennessee Texas Arizona California Colorado New Mexico Nevada Utah California Arizona Nevada Oregon Colorado Arizona Kansas Nebraska New Mexico Oklahoma Texas Utah Wyoming Connecticut Massachusetts New Jersey New York Rhode Island District of Columbia Delaware Maryland Pennsylvania Virginia West Virginia Delaware District of Columbia Maryland New Jersey Pennsylvania Florida Alabama Georgia Georgia Alabama Florida North Carolina South Carolina Tennessee Hawaii Iowa Illinois Missouri Minnesota Nebraska South Dakota Wisconsin Idaho Montana Nevada Oregon Utah Washington Wyoming Illinois Illinois Indiana Kentucky Michigan Missouri Tennessee Wisconsin Indiana Illinois Kentucky Michigan Ohio Wisconsin Kansas Colorado Missouri Nebraska Oklahoma Kentucky Illinois Indiana Missouri Ohio Tennessee Virginia West Virginia Louisiana Arkansas Mississippi Texas Massachusetts Connecticut Maine New Hampshire New York Rhode Island Vermont Maryland Delaware District of Columbia -

Trustee Liability for Spendthrift Trust Assignments

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 12 Fall 9-1-1961 Trustee Liability For Spendthrift rT ust Assignments Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation Trustee Liability For Spendthrift rT ust Assignments, 18 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 283 (1961), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol18/iss2/12 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i96i] CASE COMMENTS TRUSTEE LIABILITY FOR SPENDTHRIFT TRUST ASSIGNMENTS The once highly controversial issue concerning the validity of the spendthrift trust is no longer open, except in a very few American jurisdictions.' Support for the view favoring such trusts has been the argument that one owning property ought to be able to dispose of it as he sees fit, and except in a small minority of jurisdictions,2 either by statute3 or by decision, 4 a spendthrift trust has been held valid. Moreover, this particular trust device appears to be one that is becoming more and more regulated by statute.5 In fact many of the jurisdictions upholding the validity of the spendthrift trust have done so because of the validity of restraints on the alienation of equitable interests such as those appearing in spendthrift trusts. -

Estate Planning

Estate Planning: Wills and Trusts: The Basics Estate Planning Webinar Series • Powers of Attorney & Medical Directives • Why I Should Have An Estate Plan • Wills and Trusts - The Basics: Wills and Trusts, the differences and execution requirements. The webinar will also provide an overview as to why a trust may be necessary. • All presentations can be found at www.brouse.com 2 Estate Planning Blog For additional information, see https://www.brouse.com/trusts-estates-blog 3 Disclaimer • Any opinions offered are our own and not those of Brouse McDowell LPA. This presentation is provided for general informational and educational purposes only. No information contained in this presentation is to be construed as legal advice. This presentation is not a contract for legal advice and does not establish an attorney-client relationship. • Entering into an attorney-client relationship is a mutual agreement, requiring the exchange of information and the execution of an engagement letter between the client and Brouse McDowell LPA. 4 INTRODUCTION Wills and Trusts: The Basics What’s Important to You? 6 Estate Planning is for people 7 Estate Planning is for property 8 You need the proper Documents 9 What Are Estate Planning Documents? -Durable Power of Attorney -Health Care Power of Attorney and Living Will -Last Will and Testament -Trust 10 WHY DO I NEED A WILL AND/OR TRUST? Essential Documents: Last Will and Testament Last Will and Testament- Your Last Will and Testament provides for the distribution of your probate assets, nomination of a guardian for your minor children and designates an Executor who is responsible for finalizing your estate. -

Domestic Asset Protection Trusts in Divorce Litigation by Amy J

\\jciprod01\productn\M\MAT\29-1\MAT106.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-NOV-16 8:21 Vol. 29, 2016 DAPTs in Divorce Litigation 1 Domestic Asset Protection Trusts in Divorce Litigation by Amy J. Amundsen* I. Introduction ....................................... 2 R II. Brief Description of Domestic Asset Protection Trusts .............................................. 3 R A. States That Provide Protection for Attorneys, Trustees, and Others ........................... 4 R B. Due Diligence Procedures ..................... 7 R C. Exceptions for Family Law Judgments ......... 8 R III. DAPTs Containing Marital Property ............... 16 R A. Cases in Which Courts Have Validated DAPTs......................................... 16 R B. Ways Courts Have Invalidated DAPTs ........ 17 R 1. Bankruptcy Proceedings ................... 17 R 2. Conflict of Laws Used to Invalidate DAPT ..................................... 20 R IV. Limited Remedies if DAPTs With Marital Property Are Validated ...................................... 24 R A. Avoid the Transfer by Using UFTA/UVTA or Bankruptcy Code .............................. 24 R B. Other Assets ................................... 27 R C. Trustee as a Party/Writ of Attachment......... 28 R V. Ethical Problems With Transfers of Assets to DAPTs............................................. 28 R VI. Need for Statutory Change With Respect to Marital Property ................................... 29 R A. Presumptions .................................. 30 R B. Prenuptial/Postnuptial Language ............... 30 R C. Need for -

The Functions of Trust Law: a Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis, 73 N.Y.U

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1998 The uncF tions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis Ugo Mattei UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation Ugo Mattei, The Functions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis, 73 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 434 (1998). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/529 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Mattei Ugo Author: Ugo Mattei Source: New York University Law Review Citation: 73 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 434 (1998). Title: The Functions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis Originally published in NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW. This article is reprinted with permission from NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW and New York University School of Law. THE FUNCTIONS OF TRUST LAW: A COMPARATIVE LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS HENRY HANSMANN* UGO MATTEI** In this Article, ProfessorsHenry Hansmann and Ugo Mattei analyze the functions served by the law of trusts and ask, first, whether the basic tools of contract and agency law could fulfill the same functions and, second, whether trust law provides benefits that are not provided by the law of corporations. -

The Intention of the Settlor Under the Uniform Trust Code: Whose Property Is It, Anyway?

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 The nI tention of the Settlor ndeU r the Uniform Trust Code: Whose Property Is It, Anyway? Alan Newman Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Newman, Alan (2005) "The nI tention of the Settlor ndeU r the Uniform Trust Code: Whose Property Is It, Anyway?," Akron Law Review: Vol. 38 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol38/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Newman: The Intention of the Settlor Under the UTC NEWMAN1.DOC 5/2/2005 8:57:22 AM THE INTENTION OF THE SETTLOR UNDER THE UNIFORM TRUST CODE: WHOSE PROPERTY IS IT, ANYWAY? Alan Newman* “Our goods, if we are so fortunate to have any, are not interred with our bones, but are left behind for others to enjoy. But we like to determine who shall enjoy them and how they shall be enjoyed. Shall we not do as we wish with our own?”1 I.