Statewide Sepsis Initiative Michael Patterson, D.O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluid Resuscitation Therapy for Hemorrhagic Shock

CLINICAL CARE Fluid Resuscitation Therapy for Hemorrhagic Shock Joseph R. Spaniol vides a review of the 4 types of shock, the 4 classes of Amanda R. Knight, BA hemorrhagic shock, and the latest research on resuscita- tive fluid. The 4 types of shock are categorized into dis- Jessica L. Zebley, MS, RN tributive, obstructive, cardiogenic, and hemorrhagic Dawn Anderson, MS, RN shock. Hemorrhagic shock has been categorized into 4 Janet D. Pierce, DSN, ARNP, CCRN classes, and based on these classes, appropriate treatment can be planned. Crystalloids, colloids, dopamine, and blood products are all considered resuscitative fluid treat- ment options. Each individual case requires various resus- ■ ABSTRACT citative actions with different fluids. Healthcare Hemorrhagic shock is a severe life-threatening emergency professionals who are knowledgeable of the information affecting all organ systems of the body by depriving tissue in this review would be better prepared for patients who of sufficient oxygen and nutrients by decreasing cardiac are admitted with hemorrhagic shock, thus providing output. This article is a short review of the different types optimal care. of shock, followed by information specifically referring to hemorrhagic shock. The American College of Surgeons ■ DISTRIBUTIVE SHOCK categorized shock into 4 classes: (1) distributive; (2) Distributive shock is composed of 3 separate categories obstructive; (3) cardiogenic; and (4) hemorrhagic. based on their clinical outcome. Distributive shock can be Similarly, the classes of hemorrhagic shock are grouped categorized into (1) septic; (2) anaphylactic; and (3) neu- by signs and symptoms, amount of blood loss, and the rogenic shock. type of fluid replacement. This updated review is helpful to trauma nurses in understanding the various clinical Septic shock aspects of shock and the current recommendations for In accordance with the American College of Chest fluid resuscitation therapy following hemorrhagic shock. -

Approach to Shock.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Approach to Shock.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Approach to Shock Developed by Dr. Dustin Jacobson and Dr Suzanne Beno for PedsCases.com. December 20, 2016 My name is Dustin Jacobson, a 3rd year pediatrics resident from the University of Toronto. This podcast was supervised by Dr. Suzanne Beno, a staff physician in the division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at the University of Toronto. Today, we’ll discuss an approach to shock in children. First, we’ll define shock and understand it’s pathophysiology. Next, we’ll examine the subclassifications of shock. Last, we’ll review some basic and more advanced treatment for shock But first, let’s start with a case. Jonny is a 6-year-old male who presents with lethargy that is preceded by 2 days of a diarrheal illness. He has not urinated over the previous 24 hours. On assessment, he is tachycardic and hypotensive. He is febrile at 40 degrees Celsius, and is moaning on assessment, but spontaneously breathing. We’ll revisit this case including evaluation and management near the end of this podcast. The term “shock” is essentially a ‘catch-all’ phrase that refers to a state of inadequate oxygen or nutrient delivery for tissue metabolic demand. This broad definition incorporates many causes that eventually lead to this end-stage state. Basic oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and content of oxygen in the blood. -

Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting

9/3/2020 Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting 1 9/3/2020 Special Thanks to Our Sponsor 2 9/3/2020 Your Presenters Dr. Raymond L. Fowler, Dr. Melanie J. Lippmann, MD, FACEP, FAEMS MD FACEP James M. Atkins MD Distinguished Professor Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine of Emergency Medical Services, Brown University Chief of the Division of EMS Alpert Medical School Department of Emergency Medicine Attending Physician University of Texas Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital Southwestern Medical Center Providence, RI Dallas, TX 3 9/3/2020 Scenario SHOCK INDEX?? Pulse ÷ Systolic 4 9/3/2020 What is Shock? Shock is a progressive state of cellular hypoperfusion in which insufficient oxygen is available to meet tissue demands It is key to understand that when shock occurs, the body is in distress. The shock response is mounted by the body to attempt to maintain systolic blood pressure and brain perfusion during times of physiologic distress. This shock response can accompany a broad spectrum of clinical conditions that stress the body, ranging from heart attacks, to major infections, to allergic reactions. 5 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Shock may be caused when oxygen intake, absorption, or delivery fails, or when the cells are unable to take up and use the delivered oxygen to generate sufficient energy to carry out cellular functions. 6 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Hypovolemic Shock Distributive Shock Inadequate circulating fluid leads A precipitous increase in vascular to a diminished cardiac output, capacity as blood vessels dilate and which results in an inadequate the capillaries leak fluid, translates into delivery of oxygen to the too little peripheral vascular resistance tissues and cells and a decrease in preload, which in turn reduces cardiac output 7 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Cardiogenic Shock Obstructive Shock The heart is unable to circulate Obstruction to the forward flow of sufficient blood to meet the blood exists in the great vessels metabolic needs of the body. -

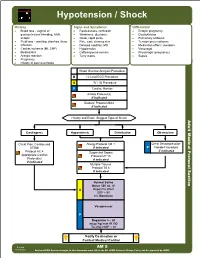

AM 05 Hypotension Shock Protocol Final 2017 Editable.Pdf

Hypotension / Shock History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Blood loss - vaginal or • Restlessness, confusion • Ectopic pregnancy gastrointestinal bleeding, AAA, • Weakness, dizziness • Dysrhythmias ectopic • Weak, rapid pulse • Pulmonary embolus • Fluid loss - vomiting, diarrhea, fever • Pale, cool, clammy skin • Tension pneumothorax • Infection • Delayed capillary refill • Medication effect / overdose • Cardiac ischemia (MI, CHF) • Hypotension • Vasovagal • Medications • Coffee-ground emesis • Physiologic (pregnancy) • Allergic reaction • Tarry stools • Sepsis • Pregnancy • History of poor oral intake Blood Glucose Analysis Procedure B 12 Lead ECG Procedure A IV / IO Procedure P Cardiac Monitor Airway Protocol(s) if indicated Diabetic Protocol AM 2 if indicated History and Exam Suggest Type of Shock Adult Medical Protocol Section Protocol Adult Medical Cardiogenic Hypovolemic Distributive Obstructive Chest Pain: Cardiac and Allergy Protocol AM 1 Chest Decompression- STEMI if indicated P Needle Procedure if indicated Protocol AC 4 Suspected Sepsis Appropriate Cardiac Protocol UP 15 Protocol(s) if indicated if indicated Multiple Trauma Protocol TB 6 if indicated A P Notify Destination or Contact Medical Control Revised AM 5 02/18/2019 Any local EMS System changes to this document must follow the NC OEMS Protocol Change Policy and be approved by OEMS Hypotension / Shock Adult Medical Protocol Section Protocol Adult Medical Pearls • Recommended Exam: Mental Status, Skin, Heart, Lungs, Abdomen, Back, Extremities, Neuro • Hypotension can be defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 90. This is not always reliable and should be interpreted in context and patients typical BP if known. Shock may be present with a normal blood pressure initially. • Shock often is present with normal vital signs and may develop insidiously. -

Distributive Shock

ASK THE EXPERT h EMERGENCY MEDICINE/CRITICAL CARE h PEER REVIEWED Distributive Shock Garret E. Pachtinger, VMD, DACVECC VETgirl; Veterinary Specialty and Emergency Center Levittown, Pennsylvania Clinical Clues YOU HAVE ASKED ... Distributive shock is generally associ- What is distributive shock, and ated with altered vasomotor tone— notably inappropriate vasodilation (eg, how do I treat it? sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome), excessive vasoconstriction THE EXPERT SAYS ... (eg, following trauma or anaphylaxis), or abnormalities in normal blood flow Shock (ie, inadequate cellular energy (eg, obstructive diseases such as gastric production or the body’s inability to dilatation-volvulus [GDV] or pericardial supply cells and tissues with oxygen and effusion)—resulting in maldistribution nutrients and remove waste products1-3) of blood flow. can cause quick clinical deterioration and requires rapid identification and Patients with septic distributive shock treatment. Distributive shock is a gen- often have hyperemic mucous mem- eral classification for syndromes that branes caused by uncontrolled vasodila- cause massive maldistribution of blood tion from inflammatory mediators and flow (seeReferences , page 96). Anaphy- cytokine release (see References, page lactic, obstructive, and septic shock are 96). Patients with anaphylactic or GDV = gastric dilatation- common forms of distributive shock. obstructive distributive shock show volvulus October 2016 cliniciansbrief.com 93 ASK THE EXPERT h EMERGENCY MEDICINE/CRITICAL CARE h PEER -

Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access

Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access Chapter 7 Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access Introduction The goal of resuscitation is to maintain adequate perfusion. Resuscitation of the wounded combatant remains a formidable challenge on the battlefield. Resuscitation begins with the placement of two large-bore IVs (16 or 18 G). The vast majority of casualties do not need any IV fluid resuscitation prior to arrival at a forward medical treatment facility. For the more seriously injured trauma patients in the presurgical setting, the goal is to deliver the patient to a surgical facility expeditiously while maximizing the patient’s chances of survival. This is accomplished using damage control resuscitation (DCR) principles at point of injury (POI), Role 1, and Role 2 facilities in order to mitigate the lethal triad of acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy. For the approximately 10% of casualties who constitute the most seriously injured, are in shock and coagulopathic, and represent potentially preventable hemorrhagic deaths, blood products should be part of the initial fluid resuscitation. This chapter will briefly address shock (including recognition, classification, treatment, definition, and basic pathophysiology), review initial and sustained fluid resuscitation, summarize currently available fluids for resuscitation, and describe vascular access techniques. Recognition and Classification of Shock Shock is a clinical condition marked by inadequate organ perfusion and tissue oxygenation, manifested by poor skin turgor, pallor, cool extremities, capillary refill greater than 2 seconds, anxiety/confusion/obtundation, tachycardia, weak or thready pulse, and hypotension. Lab findings include base deficit >5 and lactic acidosis >2 mmol/L. 73 Emergency War Surgery Hypovolemic shock: Diminished volume resulting in poor perfusion as a result of hemorrhage, diarrhea, dehydration, and burns. -

Angiotensin II in Vasodilatory Shock

Angiotensin II in Vasodilatory Shock a,b c a,d,e, Brett J. Wakefield, MD , Laurence W. Busse, MD , Ashish K. Khanna, MD * KEYWORDS Vasodilatory shock Septic shock Angiotensin II Vasopressor Blood pressure KEY POINTS Vasodilatory shock, also known as distributive shock, is characterized by decreased sys- temic vascular resistance with impaired oxygen extraction leading to profound vasodilation. The Angiotensin II for the Treatment of Vasodilatory Shock (ATHOS-3) trial demonstrated the vasopressor and catecholamine-sparing effect of angiotensin II in patients with vaso- dilatory shock. Further studies suggest Angiotensin II may offer a benefit in patients with increased severity of illness, acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy, severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and in brisk responders to minimal doses of therapy. INTRODUCTION Shock is common in the intensive care unit (ICU), and up to one-third of critically ill pa- tients are admitted to the ICU with some form of shock.1 Shock is defined as a path- ologic condition of acute and life-threatening circulatory failure resulting in inadequate tissue oxygen utilization.2 The tenets of management include treatment of the under- lying cause and blood pressure support with fluid resuscitation and vasopressor Conflict of Interest: Drs A.K. Khanna and L.W. Busse have received support from the La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company as consultants and speakers. Funding: No funding was procured for this work. a Department of General Anesthesiology, Anesthesiology Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA; b Department of Anesthesiology, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8054, St Louis, MO 63110, USA; c Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy and Sleep Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Emory St. -

Acute Liver Failure

Clinical Medicine 2020 Vol 20, No 5: 505–8 CME: HEPATOLOGY Acute liver failure Authors: Mohammed A Arshad,A Nicholas MurphyB and Mansoor N BangashC Acute liver failure is a rare syndrome and is primarily caused evidence-based guidelines on the management of acute liver by paracetamol toxicity in developed nations. Survival for failure.4 In this article, we briefly review what the generalist needs patients with acute liver failure has steadily improved over to know about ALF. the last few decades from approximately 20% to greater than 60%. This marked improvement in survival has been due to Classification ABSTRACT a combination of improvements in medical practice and the use of emergency liver transplantation in selected patients. The presentation of ALF varies according to aetiology, and Early recognition and timely initial management in the non- aetiologies vary in their relative frequency across the globe. specialist centre can significantly improve outcomes. Patients Consequently, several differing classification systems exist but should be simultaneously discussed with a transplant centre essentially all differentiate between rapidly progressive ALF and referred to critical care. Close liaison with transplant and other forms. This distinction holds prognostic significance. centres to ensure timely transfer in deteriorating patients is The UK tends to use the O’Grady classification. Patients present important. as either ‘hyperacute’, ‘acute’ or ‘subacute’ dependent upon the emergence of encephalopathy following the first detected symptoms, often jaundice (Fig 1).5 Hyperacute presentations Introduction frequently develop extrahepatic organ failure and carry a high risk of cerebral oedema and intracranial hypertension but, counter- Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare syndrome with a UK incidence intuitively, carry the best prognosis with medical treatment alone. -

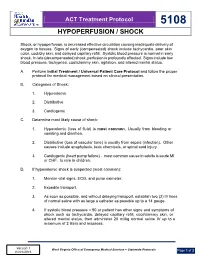

Hypoperfusion / Shock

ACT Treatment Protocol 5108 HYPOPERFUSION / SHOCK Shock, or hypoperfusion, is decreased effective circulation causing inadequate delivery of oxygen to tissues. Signs of early (compensated) shock include tachycardia, poor skin color, cool/dry skin, and delayed capillary refill. Systolic blood pressure is normal in early shock. In late (decompensated) shock, perfusion is profoundly affected. Signs include low blood pressure, tachypnea, cool/clammy skin, agitation, and altered mental status. A. Perform Initial Treatment / Universal Patient Care Protocol and follow the proper protocol for medical management based on clinical presentation. B. Categories of Shock: 1. Hypovolemic 2. Distributive 3. Cardiogenic C. Determine most likely cause of shock: 1. Hypovolemic (loss of fluid) is most common. Usually from bleeding or vomiting and diarrhea. 2. Distributive (loss of vascular tone) is usually from sepsis (infection). Other causes include anaphylaxis, toxic chemicals, or spinal cord injury. 3. Cardiogenic (heart pump failure) - most common cause in adults is acute MI or CHF. Is rare in children. D. If hypovolemic shock is suspected (most common): 1. Monitor vital signs, ECG, and pulse oximeter. 2. Expedite transport. 3. As soon as possible, and without delaying transport, establish two (2) IV lines of normal saline with as large a catheter as possible up to a 14 gauge. 4. If systolic blood pressure < 90 or patient has other signs and symptoms of shock such as tachycardia, delayed capillary refill, cool/clammy skin, or altered mental status, then administer 20 ml/kg normal saline IV up to a maximum of 2 liters and reassess. Version 1 West Virginia Office of Emergency Medical Services – Statewide Protocols 01/01/2016 Page 1 of 2 ACT Treatment Protocol 5108 HYPOPERFUSION / SHOCK 5. -

Chapter 32 Diagnosis and Management of Hypotension and Shock in the Intensive Care Unit

Diagnosis and Management of Hypotension and Shock in the Intensive Care Unit Chapter 32 DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF HYPOTENSION AND SHOCK IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT JESSICA BUNIN, MD* INTRODUCTION PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION CATEGORIES OF SHOCK GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH FOR HYPOTENSION GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF THE HYPOTENSIVE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT PATIENT MANAGEMENT OF SPECIFIC TYPES OF SHOCK Hypovolemic Shock Cardiogenic Shock Distributive Shock Obstructive Shock SUMMARY *Lieutenant Colonel, Medical Corps, US Army; Chief of the Critical Care Medicine Service, Department of Medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, Maryland 20889 327 Combat Anesthesia: The First 24 Hours INTRODUCTION Shock is a state of impaired tissue oxygenation and than 30% of blood volume has been lost. Although perfusion that can be caused by decreased oxygen hypotension and shock are not synonymous, the goals delivery, poor tissue perfusion, or impaired oxygen of treatment are the same: to restore the body’s oxygen utilization. Hypotension is a sign of shock and an indi- balance and correct hypoperfusion. This chapter will cator of advanced derangement, requiring immediate address the categories of shock, initial evaluation of a evaluation and management. For example, in hemor- hypotensive patient, general principles of shock man- rhagic shock, hypotension is not present until greater agement, and management for specific causes of shock. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION Shock represents a state of hypoperfusion that vital of organs—the heart and the brain—because of can be the final pathway for a number of conditions. the opening of arteriovenous connections to bypass Hypoperfusion from any cause results in an inflamma- capillary flow.2 tory response. -

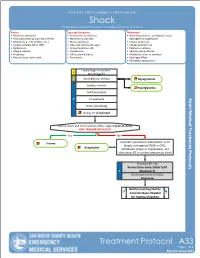

Treatment Protocol

San Mateo County Emergency Medical Services Shock For patients with poor perfusion not rapidly responsive to IV fluids History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Blood loss (amount?) • Restlessness or confusion • Shock (hypovolemic, cardiogenic, septic, • Fluid loss (vomiting, diarrhea or fever) • Weakness or dizziness neurogenic or anaphylaxis) • Infection (e.g., UTI, cellulitis, etc.) • Weak, rapid pulse • Ectopic pregnancy • Cardiac ischemia (MI or CHF) • Pale, cool, clammy skin signs • Cardiac dysrhythmias • Medications • Delayed capillary refill • Pulmonary embolus • Allergic reaction • Hypotension • Tension pneumothorax • Pregnancy • Coffee-ground emesis • Medication effect or overdose • History of poor oral intake • Tarry stools • Vasovagal effect • Physiologic (pregnancy) Apply Oxygen to maintain E goal SpO2 > 92% O Blood glucose analysis Hypoglycemia Cardiac monitor Hyperglycemia IV/IO procedure P 12-Lead ECG EtCO2 monitoring Airway TP, if indicated History, exam and circumstances often suggest (type of shock) WAS TRAUMA INVOLVED? Yes No Trauma Consider hypovolemic (dehydration or GI bleed), cardiogenic (STEMI or CHF), Anaphylaxis distributive (sepsis or anaphylaxis), and obstructive (PE or cardiac tamponade) shock If systolic BP < 90 Normal Saline bolus 500ml IV/IO P Maximum 2L If unresponsive to IV fluids, Dopamine Notify receiving facility. Consider Base Hospital for medical direction Treatment Protocol A33 Page 1 of 2 EffectiveEffective November October 2018 2019 San Mateo County Emergency Medical Services Shock For patients with poor perfusion not rapidly responsive to IV fluids Pearls • Hypotension can be defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 90mmHg. This is not always reliable and should be interpreted in context with the patient’s typical BP, if known. Shock may be present with a seemingly normal blood pressure initially. -

Shock Pathophysiology

3 CE Credits Shock Pathophysiology Elizabeth Thomovsky, DVM, MS, DACVECC Paula A. Johnson, DVM Purdue University Abstract: Shock, defined as the state where oxygen delivery to tissues is inadequate for the demand, is a common condition in veterinary patients and has a high mortality rate if left untreated. The key to a successful outcome for any patient in shock involves having a clear understanding of the pathophysiology and compensatory mechanisms associated with shock. This understanding allows more efficient identification of patients in shock based on clinical signs and timely initiation of appropriate therapies based on the type and stage of shock identified. hock is a condition that is commonly seen in practice but Anaerobic metabolism just as commonly is not completely understood. This review focuses on the body’s compensatory responses to shock and Production and release of lactate, cytokines, prostaglandins, nitric oxide, etc. S the clinical signs to help provide practitioners with a better under- standing of what shock is and how it can be categorized. Treatment is Increased capillary Decreased vasomotor tone discussed in the context ofThomovsky the pathophysiology E, et al. Shock pathophysiology but is .not Compend covered Contin Cellular swelling Thomovsky E, et al. Shock pathophysiology. Compend Contin permeability in depth. Educ Vet 2013;35(8)Educ Vet 2013;35(8). Definitions Interstitial edema The first difficulty comes in defining shock. At its most elemental, the definition can be stated as: Cellular dysfunction Circulatory collapse 1 oxygen delivery ≠ oxygen consumption (DO2 ≠ VO2). GI barrier breakdown + translocation of gut bacteria Glucose Glucose Consumptive coagulopathy Anaerobic AnaerobicMetabolism Metabolism.