Contrast 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Click Here to Download the PDF File

THE CHALLENGES OF CREATING SOCIAL CAPITAL AND INCREASING COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION IN A DIVERSE POPULATION: IMPLICATIONS FOR THEORY, POLICY AND PRACTICE BASED ON A CASE STUDY OF A CANADIAN HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE By Marika Morris, B.A. (Highest Honours), M.A., Carleton University A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Canadian Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario August, 2010 ©Marika Morris 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et ?F? Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-7056 1 -2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70561-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. -

Freedom Teachers : Northern White Women Teaching in Southern Black Communities, 1860'S and 1960'S

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2001 Freedom teachers : Northern White women teaching in Southern Black communities, 1860's and 1960's. Judith C. Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Hudson, Judith C., "Freedom teachers : Northern White women teaching in Southern Black communities, 1860's and 1960's." (2001). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5562. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5562 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM TEACHERS: NORTHERN WHITE WOMEN TEACHING IN SOUTHERN BLACK COMMUNITIES, 1860s AND 1960s A Dissertation Presented by JUDITH C. HUDSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2001 Social Justice Education Program © Copyright by Judith C. Hudson 2001 All Rights Reserved FREEDOM TEACHERS: NORTHERN WHITE WOMEN TEACHING IN SOUTHERN BLACK COMMUNITIES, 1860s AND 1960s A Dissertation Presented by JUDITH C. HUDSON Approved as to style and content by: Maurianne Adams, Chair ()pMyu-cAI oyLi Arlene Voski Avakian, Member ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . I would like to acknowledge the financial support of the American Association of University Women. I received a Career Development Grant which allowed me, on a full¬ time basis, to begin my doctoral study of White women’s anti-racism work. -

Ilistung Spec:131

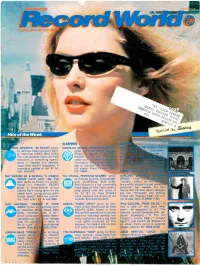

-FEBRUARY 28,1981 s Po, (tZtoo 4)0 1. .(1 C06/24,a402-(7/2,4 tE0 ic . ilistung SPeC:131.. SLEEPERS ND JEFFREYS, "96 TEARS" (prod. EMMYLOU HARRIS, -MISTER SAM' by Jeffreys-Clearmountain) (writ- (prod. by Ahern) (writer..f' er: Martinez) (ABKO, BMI) (3:06). (EdwinH.Morris&" The unforgettable organ riff intro ASCAP)(2:20).Putifr`!- forewarns of somethi-hg .special watch your speakers flo about to happen and Jeffreys' Emmylou's luscious voc vocal fever doesn't disappoint. .4 age to recreate the Ch marvelous update of the '67 hit full sound. Great for any to Epic 19-51008. WB 49684. RAY PARKER JR. & RAYDIO, "A WOMAN THE FOOLS, "RUNNING SCARED" (prod. GAHLANu NEEDS LOVE (JustLike You by Poncia) (writers: Orbison-Mel- ARTIST." From tha *Sr Do)" (prod. by Parker Jr.) (writer: son: (Acuff -Rose,BMI)(2:28). "Modern Lovers," it's obvious,k ParkerJr.)(Raydiola,ASCAP;, Roy Orbison is a hot commodity this prolific songwrte- and dramat (3:46). A velvet -smooth chorus these days and the Fools make a performerhasmeldedthetwo adorns Ray's loving tenor on the wise choice withthis cover of talents into his ideal album. Reggae classy hook, giviig st-ong multi - his'61 hit.Mike Girard's poplike"Christine" andchilling format appeal. From theJpco m- vocal captures the drama of the finales like "Mystery Kids" will cor- in g "Just Love" LP. A-ista 0592 original. EMI -America 8072. ner airplay. Epic JE 36983 (7.98) DAN HARTMAN, "HEAVEN IN YOUR HAWKS, "RIGHT AWAY" (prod. by Wer- PHIL COLLINS, "FACE VALUE." At ARMS" (prod. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

OCTOBER 1986 Reflections on the NAMM Show

in this issue . VOL. 10, NO. 10 Features Cover Photo by Jaeger Kotos Columns DAVE WECKL EDUCATION ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS MIDI And The Electronic Drummer: Part 1 by Jim Fiore 46 ROCK PERSPECTIVES Applying The Paradiddle-diddle by Jeff Macko 62 TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS A Guide To Full-Time Employment: Part 2 by Michael Stevens 68 DRUM SOLOIST Dave Weckl: "Step It" by Ken Ross 70 CONCEPTS Kotos Mousey Alexander: Drumming And Courage Jaeger by Roy Burns 92 by CLUB SCENE Photo On The Clock For the past couple of years, musicians around New York by Rick Van Horn 94 have been referring to Dave Weckl as "the next guy." Now, with his exposure in Chick Corea's Elektric Band, the rest of the world is getting the chance to find out why. by Jeff Potter 16 EQUIPMENT SHOP TALK BOBBY BLOTZER Dream Product Contest Results 82 Providing the beat for Ratt has earned Bobby Blotzer a PRODUCT CLOSE-UP reputation as a first-class heavy metal drummer. While he For Hands And Feet appreciates the recognition, he's quick to point out that metal by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 96 is not all that he can do. by Anne M. Raso 22 JUST DRUMS NAMM '86 From A to Z STAYING IN SHAPE: by Rick Mattingly 100 TIPS FROM THE PROS PART 1 PROFILES The world's top drummers share the personal fitness exercises, ON THE MOVE diets, and warm-ups that keep them in shape for the physical Biddie Freed: The Search For Respect aspects of drumming. by Russ Lewellen 40 by Ron Spagnardi 26 RANDY WRIGHT The drummer, featured vocalist, and bandleader in Barbara NEWS Mandrell's group discusses recent changes that have made the UPDATE 6 group more contemporary, and explains how Barbara's nearly fatal auto accident affected the whole band. -

Unruly Cities?: Order/Disorder

Downloaded by [Central Uni Library Bucharest] at 08:33 27 September 2013 Unruly Cities? Steve Pile is Lecturer in the Faculty of Social Sciences at The Open University. His recent books include The Body and the City (1996), Geographies of Resistance (1997, co-edited with Michael Keith) and Places through the Body (1998, co-edited with Heidi J.Nast). Christopher Brook is Lecturer in the Faculty of Social Sciences at The Open University. His recent books include A Global World? (1995, co-edited with James Anderson and Allan Cochrane) and Asia Pacific in the New World Order (1997, co-edited with Anthony McGrew). Gerry Mooney is Staff Tutor in Social Policy at The Open University. He has published widely on issues relating to developments in social policy and in the field of urban studies. He is currently editing a collection of essays on the theme of Class Struggles and Social Welfare with Michael Lavalette. Downloaded by [Central Uni Library Bucharest] at 08:33 27 September 2013 UNDERSTANDING CITIES This book is part of a series produced in association with The Open University. The complete list of books in the series is as follows: City Worlds, edited by Doreen Massey, John Allen and Steve Pile Unsettling Cities: Movement/Settlement, edited by John Allen, Doreen Massey and Michael Pryke Unruly Cities? Order/Disorder, edited by Steve Pile, Christopher Brook and Gerry Mooney The books form part of the Open University course DD304 Understanding Cities. Details of this and any other Open University course can be obtained from the Courses Reservations Centre, PO Box 724, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6ZS, United Kingdom: tel. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

PAUL COLVIN - Poems

Poetry Series PAUL COLVIN - poems - Publication Date: 2011 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive PAUL COLVIN(31/01/1954) I was born in sunny Glasgow but left in 1980 to work in London and still here. My poems are very varied, from love to childhood reminisces to football to sorrow, illness and death with some children's poems thrown in. And a few Glasgow/Scottish themes as well. I would like to suggest a few poems: A Soldier's Last Thoughts - About death in war. Dignity and Pride - About dementia. Flower of My Fathers - Scotland's national emblem. Lilac Time - For the ladies. My ladybird - A warming rhyme. One Night As She Lay Sleeping. A sad love poem Wildness - A poem about the Cairngorms with a twist. Henrik Larsson - Football Legend. I hope you enjoy them. I try to answer all questions and thank you to those who have posted comments. Paul. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Bedtime Song Sleepy head, sleepy head, go to bed Lie down, lie down, and rest your head And when you give the biggest sigh, I’ll sing to you a lullaby. I’ll sing to you of distant lands I’ll sing to you of diamonds I’ll sing to you of starry skies And this will be your lullaby. PAUL COLVIN www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 A Birdseye's View. The rooftops of Italia’s Alps stand neatly in a row And down below a river flows by a road that no-one knows, Puffs of cloud look just like smoke as though the sky’s on fire, They nestle upon these alpine peaks, growing ever higher. -

With Lead Vocal) Song Package

2389 Multiplex (with lead vocal) song package This song package is made available from CAVS Download Service . Update 2011/07/01 Title Artist 07/24 KEVON EDMONDS 98.6 KEITH 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY BRITNEY SPEARS 13TH, THE CURE, THE 4 MINUTES AVANT 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN 4TH OF JULY SHOOTER JENNINGS 99 RED BALLOONS NENA 99.9% SURE BRIAN MCCOMAS A A PICTURE OF ME (WITHOUT YOU) GEORGE JONES AARON'S PARTY (COME GET IT) CARTER, AARON ABACAB GENESIS ABC JACKSON 5 ABIDE WITH ME TRADITIONAL ABSOLUTELY (STORY OF A GIRL) NINE DAYS ACE IN THE HOLE STRAIT, GEORGE ACHY BREAKY HEART BILLY RAY CYRUS ACHY BREAKY SONG WEIRD AL YANKOVIC ADAM'S SONG BLINK 182 ADDICTED SIMPLE PLAN ADDICTED TO LOVE ROBERT PALMER ADRIENNE CALLING, THE AFFAIR OF THE HEART SPRINGFIELD, RICK AFTER CLOSING TIME HOUSTON, DAVID / MANDRELL, BARBARA AFTER ME SALIVA AFTER MIDNIGHT ERIC CLAPTON AGAINST ALL ODDS PHIL COLLINS AGAINST ALL ODDS (2000) MARIAH CAREY AGE AIN'T NOTHING BUT A NUMBER AALIYAH AIN'T LOVE A BITCH STEWART, ROD AIN'T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH MARVIN GAYE/T. TERRELL AIN'T NO STOPPIN' US NOW MCFADDEN & WHITEHEAD AIN'T NO SUNSHINE (1971) WITHERS, BILL AIN'T NO SUNSHINE (1972) JACKSON, MICHAEL AIN'T NO WOMAN LIKE THE ONE I'VE GOT FOUR TOPS AIN'T NOTHING LIKE THE REAL THING GILL, VINCE / KNIGHT, GLADYS AIN'T THAT A SHAME FATS DOMINO AIN'T THAT PECULIAR GAYE, MARVIN AIN'T TOO PROUD TO BEG TEMPTATIONS, THE ALFIE ALLEN, LILY ALIENS EXIST BLINK 182 ALL ALONE AM I LEE, BRENDA ALL BY MYSELF DION/ CELION ALL DOWNHILL FROM HERE NEW FOUND GLORY ALL -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Building Values Into the Design of Pervasive Mobile Technologies a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Building Values into the Design of Pervasive Mobile Technologies A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies by Katherine Carol Shilton 2011 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License. Katherine Carol Shilton 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Participatory Sensing, Values, and the Structure of Design……………………...1 Chapter 2: Literature Review – Situating Participatory Sensing……………………………30 Chapter 3: Methods……………………………………………………………………….83 Chapter 4: Findings – Observing Values in Design at CENS………………………….…100 Chapter 5: Discussion – Values Levers and Critical Technical Practice…………………..192 Chapter 6: Conclusions…………………………………………………………………..220 Appendix: Code Definitions………………………………………………………….......231 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..237 DETAILED TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Participatory Sensing, Values, and the Structure of Design ....................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Values and pervasive mobile technologies .............................................................................. 3 Surveillance and participatory sensing ...................................................................................... 6 Research questions ..................................................................................................................... -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

MUSICAL HORN SONG LIST.Pdf

PMMI Electronics Song Directory for "THE" HORN & THE Ultimate HORN Ordering Instructions When programming THE Ultimate HORN, you may choose 100 songs, or fewer, with the total length under or equal to 60,700. (Ultimate Horns purchased after January 1, 2002 can have a total length up to 120,000). When programming "THE" HORN, you may choose 64 songs, or fewer, with the total length under or equal to 31,730. To provide us with the correct number of songs and length, simply mark or circle your selections and then add the song lengths found in the left-hand column next to the songs you have chosen. Then compare the total length against the limits shown above. Send your list of songs along with the horn module box to us at the address at the bottom of this page. The special-program or re-programming charge is $75.00 (plus $6.00 S&H within continental USA). Please call or write us if you have any questions. Songs lists can be sorted by category or by alphabet. Please indicate your preference below. In addition, you may select one song to be your first song (song number 00). _________ Sort by Alphabet Optional First Song Choice _________ Sort by Category ____________________________________ Thank You ! Length Song Name Length Song Name Patriotic / March Patriotic / March 386 AIR FORCE SONG (L) 64 CAISSON'S SONG (S) 82 AIR FORCE SONG (S) 830 EL CAPITAN (L) 172 AMERICA (L) 434 EL CAPITAN (S) 70 AMERICA (S) 1952 ENTRY OF THE GLADIATORS (L) 260 AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL 456 ENTRY OF THE GLADIATORS (S) 908 AMERICAN PATROL 132 FANFARE 254 ANCHORS AWAY