AHRLJ 2 2020.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother Tongue Education: a Case Study of Grade Three Children

MOTHER TONGUE EDUCATION: A CASE STUDY OF GRADE THREE CHILDREN By MARTHA KHOSA A dissertation submitted as partial fulfillment for the MASTERS DEGREE IN EDUCATION in Educational Linguistics in the Faculty of Education at the University of Johannesburg Supervisor: Dr. L. Kajee 2012 i DECLARATION I declare that this research paper is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Masters in Educational Linguistics at the University of Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other University. Signed: ……………………………………………… Date: ………………………………………………… ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my: • Dear husband Phineas Khosa for his continuous support and encouragement. • Two children, Vincent and Rose for being so understanding and patient throughout my studies. • Mother, Sarah Nomvela for her prayers and support during every step of my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge and thank the following people for their contributions: Dr Leila Kajee, my supervisor, for all her encouragement, wisdom, patience and guidance as well as for reading through my numerous drafts with insight and giving helpful suggestions. All the learners and parents, for all their time, interest and information, especially those that I interviewed. Gail Tshimbane, for conducting the Grade 3 lessons and for her unwavering support throughout the research project. The Limpopo Department of Education, for permitting me to conduct my research at the foundation phase school in the area of Khujwana under Mopani district. My family, especially my partner in life, Phineas, and my two children, Vincent and Rose for the support and understanding. Above all, I thank God almighty who has endowed me with the wisdom, ability, competence, motivation and persistence, despite all the challenges to successfully complete this study. -

United Nations Common Country Analysis of the Kingdom of Eswatini April 2020

UNITED NATIONS COMMON COUNTRY ANALYSIS OF THE KINGDOM OF ESWATINI APRIL 2020 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 10 CHAPTER 1: COUNTRY CONTEXT ................................................................................................... 12 1.1. GOVERNANCE ...................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 ECONOMIC SITUATION ........................................................................................................ 14 1.3 SOCIAL DIMENSION ............................................................................................................. 17 1.4 HEALTH SECTOR ................................................................................................................... 17 1.5 WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE .................................................................................... 19 1.6 EDUCATION SECTOR ............................................................................................................ 20 1.7 JUSTICE SYSTEM—RULE OF LAW ........................................................................................ 22 1.8 VIOLENCE -

Sexual Abuse of the Vulnerable by Catholic Clergy Thomas P

Sexual Abuse of the Vulnerable by Catholic Clergy Thomas P. Doyle, J.C.D., C.A.D.C. exual abuse of the vulnerable by Catholic clergy (deacons, priests and bishops) was a little known phenomenon until the mid-eighties. Widespread publicity sur- S rounding a case from a diocese in Louisiana in 1984 began a socio-historical process that would reveal one of the Church’s must shameful secrets, the widespread, systemic sexual violation of children, young adolescents and vulnerable adults by men who hold one of the most trusted positions in our society (cf. Berry, 1992). The steady stream of reports was not obvious was the sexual abuse itself. This Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, contained limited to the southern United States. It was was especially shocking and scandalous an explicit condemnation of sex between soon apparent that this was a grave situa- because the perpetrators were priests and adult males and young boys. There were no tion for the Catholic Church throughout the in some cases, bishops. For many it was clergy as such at that time nor were United States. Although the Vatican at first difficult, if not impossible, to resolve the bishops and priests, as they are now claimed this was an American problem, the contradiction between the widespread ins- known, in a separate social and theological steady stream of revelations quickly spread tances of one of society’s most despicable class. The first legislation proscribing what to other English speaking countries. crimes and the stunning revelation that the later became known as pederasty was pas- Reports in other countries soon confirmed perpetrators were front-line leaders of the sed by a group of bishops at the Synod of what insightful observers predicted: it was largest and oldest Christian denomination, Elvira in southern Spain in 309 AD. -

Clergy Sexual Abuse: Annotated Bibliography of Conceptual and Practical Resources

Clergy Sexual Abuse: Annotated Bibliography of Conceptual and Practical Resources. Preface The phenomenon of sexual abuse as committed by persons in fiduciary relationships is widespread among helping professions and is international in scope. This bibliography is oriented to several specific contexts in which that phenomenon occurs. The first context is the religious community, specifically Christian churches, and particularly in the U.S. This is the context of occurrence that I best know and understand. The second context for the phenomenon is the professional role of clergy, a religious vocation and culture of which I am a part. While the preponderance of sources cited in this bibliography reflect those two settings, the intent is to be as comprehensive as possible about sexual boundary violations within the religious community. Many of the books included in this bibliography were obtained through interlibrary loan services that are available at both U.S. public and academic libraries. Many of the articles that are listed were obtained through academic libraries. Daily newspaper media sources are generally excluded from this bibliography for practical reasons due to the large quantity, lack of access, and concerns about accuracy and completeness. In most instances, author descriptions and affiliations refer to status at time of publication. In the absence of a subject or name index for this bibliography, the Internet user may trace key words in this PDF format through the standard find or search feature that is available as a pull-down menu option on the user’s computer. The availability of this document on the Internet is provided by AdvocateWeb, a nonprofit corporation that serves an international community and performs an exceptional service for those who care about this topic. -

World Leaders October 2018

Information as of 29 November 2018 has been used in preparation of this directory. PREFACE Key To Abbreviations Adm. Admiral Admin. Administrative, Administration Asst. Assistant Brig. Brigadier Capt. Captain Cdr. Commander Cdte. Comandante Chmn. Chairman, Chairwoman Col. Colonel Ctte. Committee Del. Delegate Dep. Deputy Dept. Department Dir. Director Div. Division Dr. Doctor Eng. Engineer Fd. Mar. Field Marshal Fed. Federal Gen. General Govt. Government Intl. International Lt. Lieutenant Maj. Major Mar. Marshal Mbr. Member Min. Minister, Ministry NDE No Diplomatic Exchange Org. Organization Pres. President Prof. Professor RAdm. Rear Admiral Ret. Retired Sec. Secretary VAdm. Vice Admiral VMar. Vice Marshal Afghanistan Last Updated: 20 Dec 2017 Pres. Ashraf GHANI CEO Abdullah ABDULLAH, Dr. First Vice Pres. Abdul Rashid DOSTAM Second Vice Pres. Sarwar DANESH First Deputy CEO Khyal Mohammad KHAN Second Deputy CEO Mohammad MOHAQQEQ Min. of Agriculture, Irrigation, & Livestock Nasir Ahmad DURRANI Min. of Border & Tribal Affairs Gul Agha SHERZAI Min. of Commerce & Industry Homayoun RASA Min. of Counternarcotics Salamat AZIMI Min. of Defense Tariq Shah BAHRAMI Min. of Economy Mohammad Mustafa MASTOOR Min. of Education Mohammad Ibrahim SHINWARI Min. of Energy & Water Ali Ahmad OSMANI Min. of Finance Eklil Ahmad HAKIMI Min. of Foreign Affairs Salahuddin RABBANI Min. of Hajj & Islamic Affairs Faiz Mohammad OSMANI Min. of Higher Education Najibullah Khwaja OMARI Min. of Information & Culture Mohammad Rasul BAWARI Min. of Interior Wais Ahmad BARMAK Min. of Justice Abdul Basir ANWAR Min. of Martyred, Disabled, Labor, & Social Affairs Faizullah ZAKI Min. of Mines & Petroleum Min. of Parliamentary Affairs Faruq WARDAK Min. of Public Health Ferozuddin FEROZ Min. of Public Works Yama YARI Min. -

Shrinking and Sinking

Press Freedom Index Report 2011 Uganda Shrinking and sinking Human Rights Network for Journalists - Uganda with the support of Open Society Initiative for East Africa Press Freedom Index Report 2011 Uganda Shrinking and sinking Human Rights Network for Journalists - Uganda with the support of Open Society Initiative for East Africa Kivebulaya Road Mengo Bulange P.O.Box 71314 Kampala Tel: +256 414 272934 +256 414 667627 Email: [email protected] www.hrnjuganda.org Cover Photo: Micheal Mugabi Regional Police Commander Kampala North holding a video camera at Lubigi wetland after confiscating it from a journalist Umar Kyeyune of Uganda Broadcsating Corporation, on 18 May 2011. HRNJ-Uganda Photo Februray 2012 Contents Who we are ............................................................1 Acknowledgement ...................................................2 Background ............................................................3 Report objective ......................................................3 Our Methodology .....................................................3 Introduction ............................................................5 Attacks on journalists ...............................................7 Journalists physically attacked and injured ..........7 Foreign journalist killed ..................................12 Arrest and detention ......................................13 Media houses raided ......................................15 Confrontations and verbal attacks ....................17 Confiscation of tools of trade ...........................18 -

South Africa Political Snapshot New ANC President Ramaphosa’S Mixed Hand Holds Promise for South Africa’S Future

South Africa Political Snapshot New ANC President Ramaphosa’s mixed hand holds promise for South Africa’s future South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress, yesterday (20 December) concluded its 54th National Conference at which it elected a new leadership. South African Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa was announced the ANC’s new leader against a backdrop of fast-deteriorating investor confidence in the country. The new team will likely direct the ANC’s leadership of the country for the next five years and beyond. Mr Ramaphosa’s victory is not complete. The election results have been the closest they have been of any ANC leadership election in recent times. The results for the top six leaders of the ANC (Deputy President, National Chairperson, Secretary-General, Treasurer-General and Deputy Secretary-General) and the 80-member National Executive Committee (NEC - the highest decision-making body of the party between conferences) also represent a near 50-50 composition of the two main factions of the ANC. Jacob Zuma, Mr Ramaphosa’s predecessor, still retains the presidency of South Africa’s government (the next general election is still 18 months away). It enables Mr Zuma to state positions difficult for the new ANC leadership to find clawback on, and to leverage whatever is left of his expanded patronage network where it remains in place. A pointed reminder of this was delivered on the morning the ANC National Conference commenced, when President Zuma committed the government to provide free tertiary education for students from homes with combined incomes of below R600 000 – an commitment termed unaffordable by an expansive judicial investigation, designed to delay his removal from office and to paint him as a victim in the event it may be attempted. -

Fighting for the Future

Fighting for the Future Adult Survivors Work to Protect Children & End the Culture of Clergy Sexual Abuse An NGO Report The Holy See . The Convention on the Rights of the Child . The Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography February 2013 Submitted by The Center for Constitutional Rights a Member of the International Federation for Human Rights on behalf of The Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests Center for Constitutional Rights 666 Broadway, 7th Floor, New York, NY, U.S.A. 10012 Tel. +1 (212) 614-6431 ▪ Fax +1 (212) 614-6499 [email protected] ▪ www.ccrjustice.org Cover Photos: The photos on the Report: This report was prepared by cover are of members of the Survivors Katherine Gallagher and Pam Spees, Network of Those Abused by Priests at Senior Staff Attorneys at the Center the age that they were sexually for Constitutional Rights, with the abused. They have consented to the research assistance of Rebecca Landy use of their photos to help raise and Ellyse Borghi and Aliya Hussain. awareness and call attention to this crisis. Table of Contents Foreword I. General Considerations: Overview 1 The Policies and Practices of the Holy See Helped to Perpetuate the Violations 3 The Acts at Issue: Torture, Rape and Other Forms of Sexual Violence 4 Violations of Principles Enshrined in the CRC and OPSC 5 II. Legal Status and Structure of the Holy See and Implications for Fulfillment of Its Obligations Under the CRC and OPSC 8 Privileging Canon Law and Procedures and Lack of Cooperation with Civil Authorities 10 III. -

The New Cabinet

Response May 30th 2019 The New Cabinet President Cyril Ramaphosa’s cabinet contains quite a number of bold and unexpected appointments, and he has certainly shifted the balance in favour of female and younger politicians. At the same time, a large number of mediocre ministers have survived, or been moved sideways, while some of the most experienced ones have been discarded. It is significant that the head of the ANC Women’s League, Bathabile Dlamini, has been left out – the fact that her powerful position within the party was not enough to keep her in cabinet may be indicative of the President’s growing strength. She joins another Zuma loyalist, Nomvula Mokonyane, on the sidelines, but other strong Zuma supporters have survived. Lindiwe Zulu, for example, achieved nothing of note in five years as Minister of Small Business Development, but has now been given the crucial portfolio of social development; and Nathi Mthethwa has been given sports in addition to arts and culture. The inclusion of Patricia de Lille was unforeseen, and it will be fascinating to see how, as one of the more outspokenly critical opposition figures, she works within the framework of shared cabinet responsibility. Ms de Lille has shown herself willing to change parties on a regular basis and this appointment may presage her absorbtion into the ANC. On the other hand, it may also signal an intention to experiment with a more inclusive model of government, reminiscent of the ‘government of national unity’ that Nelson Mandela favoured. During her time as Mayor of Cape Town Ms de Lille emphasised issues of spatial planning and land-use, and this may have prompted Mr Ramaphosa to entrust her with management of the Department of Public Works’ massive land and property holdings. -

Say Canadian Bishops Responding to US Abuse Crisis

Catholics are ‘rightly ashamed’, say Canadian bishops responding to U.S. abuse crisis Canada’s Catholic bishops have joined their American counterparts in expressing heartbreak and sorrow over the unfolding clerical abuse crisis south of the border. “Catholics across our country are rightly ashamed and saddened regarding the findings of the Pennsylvania Investigating Grand Jury,” said an Aug. 20 statement from the executive committee of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB). Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops “With Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, President of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, we reiterate the profound sadness that we as Bishops feel each time we learn about the harm caused as a result of abuse by Church leaders of any rank.” The grand jury reported on decades of clerical sexual abuse involving more than 1,000 minors and about 300 predator priests as well as on the bishops who covered up their crimes. “The Bishops of Canada treat with great seriousness instances of sexual abuse of minors and inappropriate conduct on the part of all pastoral workers – be they fellow Bishops, other clergy, consecrated persons or laity,” the CCCB statement said. “National guidelines for the protection of minors have been in place in Canada since 1992, which dioceses and eparchies across the country have applied in their local policies and protocols.” Canada’s Catholic bishops developed protocols long before their American counterparts because the clerical sexual abuse crisis hit Canada in the late 1980s with the revelations of abuse by Irish Catholic Brothers at Mount Cashel Orphanage, followed by the Winter Commission set up by the St. -

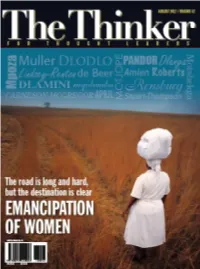

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

July-September SNAP Newsletter

ESWATINI NATIONAL AIDS PROGRAMME QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER July-September 2020 v Volume 4, Issue 3 October2020 v “Government is committed to continue investments in HIV response and to reach the ambitious goals of stopping new infections and AIDS related deaths to achieve the vision of ending AIDS by 2022.” HIV Self-Testing Campaign Launch Adolescent Campaign Launch v Inside this Issue Programme Manager’s Foreword ________________________ 3 Adolescent Campaign Launch __________________________ 4-5 Red Cross Volunteers for Manzini Door to Door Campaign on COVID-19 Commissioned by the Ministry of Health ______ 6 Red Cross Volunteers for Manzini Door to Door Campaign on COVID-19 Commissioned by the Ministry of Health ______ 7 HIV Self-Testing Campaign Launch _____________________ 8-10 Hygiene Packs Distribution ____________________________ 11 World Health Organisation Donated Medical Supplies Worth E4.5 Million __________________________________________ 12 Social Corner _________________________________________ 13 ESWATINI NATIONAL AIDS PROGRAMME Volume 4, Issue 3 FOREWORD SNAP Programme Manager Mr Muhle Dlamini The Eswatini National AIDS Programme (SNAP) was involved in the adolescent cam- paign launch, which aimed at prioritising and further MOH and NERCHAs existing initia- tives, to ensure that health care remains adequate, professional, confidential and youth friendly to break down barriers to health and wellbeing. The aim of the campaign was to keep adolescent health even during the COVID-19 pan- demic with an enhanced understanding of HIV/AIDS for adolescents and to ensure that they continue to protect themselves from HIV, unplanned pregnancies and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Despite achieving the (95/95/95) global target there still is a long way to go and together as a nation we can achieve the goal of having an HIV/AIDS free generation.