Two Men and a Spoon Go Hill Walking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Residents

• ' • PRIVATE RESIDENTS. Abbott 'C. E. Trereiffe, Roche S.O A.llport S. Market sq. Padstow S.O A.nthony E. K. Tregenna pl. St. Ives Abbott James, 27 Dunstanville ter. Allport William Sandford, St. Petroc, Anwyl Miss, Stonehurst, Newqnay Falmouth Padstow S.O Appleton Harry, Park braws, The A.bbott S. M. II Trewirgie rd.Redrth A.mbrose Samuel Bertram, 2 New Lizard S.O Abelspies John Frederick Charles, Upland terrace, Falmouth Apps H. Mount pleasant, Padstow S.O The Villas, Charlestown, St. A.ustell Amor Alfrred, 216 Alma ·ter. Penzance Arche·r A. ·8 'Woodlane cres. F!!.lmouth A.braham John, Barn street, Liskeard Amor Arthur, 5 Coulson ter. Penzance Archer Charles Gordon J.P. Trelaske, .A.braham Thomas, Osborne house,Pen- Ancell Rt. I Home Park vils. Saltash Lewannick, Launceston darves road, Camborne Andain John, St. Mawes S.O Archer William, Kingwood, Alexandra .A.eford Miss, Lytham, Du.nheved rd. Anderson Lt.-Col. Alexander, Kenwyn road, Penzance Launceston house, Kenwyn road, Truro Ardouin A. 8 Belle vue ter. Penzance .A.ckermann Miss, Brisbane house, Anderson Capt. Henry, 218a, Ohape[ st. Argall Mrs. F. 10 Lansdowne rd. Watering hill, St. Austell Penzanca Falmouth .A.cland Misses, Kensey cottage, St. Anderson Capt. James Sydney, Tre- Armitage E. E. 6 Park ter. Falmth Stephens, Launceston vone, Woodland, F~lmouth Armstrong John Scobell, Nanceal- Adam W. Gwendrock, Wadebdg. S.O Anderson R. Be_an, Wmdsor ho. Castle verne, Madron, Hea Moor S.O .!.dames W. Helford, St. Martin S.O street, Bodmm Armstrong Miss,'I5 North par.Penzanca Adams Rev. Arthur B.A. -

11 Plymouth to Bodmin Parkway Via Dobwalls | Liskeard | Tideford | Landrake | Saltash

11 Plymouth to Bodmin Parkway via Dobwalls | Liskeard | Tideford | Landrake | Saltash COVID 19 Mondays to Saturdays Route 11 towards Bodmin Route 11 towards Plymouth Plymouth Royal Parade (A7) 0835 1035 1235 1435 1635 1835 1935 Bodmin Parkway Station 1010 1210 1410 1610 1810 2010 Railway Station Saltash Road 0839 1039 1239 1439 1639 1839 1939 Trago Mills 1020 1220 1420 1620 Milehouse Alma Road 0842 1042 1242 1442 1642 1842 1942 Dobwalls Methodist Church 1027 1227 1427 1627 1823 2023 St Budeaux Square [S1] 0850 1050 1250 1450 1650 1849 1949 Liskeard Lloyds Bank 0740 0840 1040 1240 1440 1640 1840 2032 Saltash Fore Street 0855 1055 1255 1455 1655 1854 1954 Liskeard Dental Centre 0741 0841 1041 1241 1441 1641 1841 Callington Road shops 0858 1058 1258 1458 1658 1857 1957 Liskeard Charter Way Morrisons 0744 0844 1044 1244 1444 1644 1844 Burraton Plough Green 0900 1100 1300 1500 1700 1859 1959 Lower Clicker Hayloft 0748 0848 1048 1248 1448 1648 1848 Landrake footbridge 0905 1105 1305 1505 1705 1904 2004 Trerulefoot Garage 0751 0851 1051 1251 1451 1651 1851 Tideford Quay Road 0908 1108 1308 1508 1708 1907 2007 Tideford Brick Shelter 0754 0854 1054 1254 1454 1654 1854 Trerulefoot Garage 0911 1111 1311 1511 1712 1910 2010 Landrake footbridge 0757 0857 1057 1257 1457 1657 1857 Lower Clicker Hayloft 0914 1114 1314 1514 1715 1913 2013 Burraton Ploughboy 0802 0902 1102 1302 1502 1702 1902 Liskeard Charter Way Morrisons 0919 1119 1319 1519 1720 1918 2018 Callington Road shops 0804 0904 1104 1304 1504 1704 1904 Liskeard Dental Centre 0921 1121 1321 1521 -

Cornwall Visitor Guide for Dog Owners

Lost Dogs www.visitcornwall.com FREE GUIDE If you have lost your dog please contact the appropriate local Dog Warden/District Council as soon as possible. All dogs are required by law to wear a dog collar and tag Cornwall Visitor bearing the name and address of the owner. If you are on holiday it is wise to have a temporary tag with your holiday address on it. Guide for NORTH CORNWALL KERRIER Dog Warden Service Dog Welfare and Dog Owners North Cornwall District Council Enforcement Officer Trevanion Road Kerrier District Council Wadebridge · PL27 7NU Council Offices Tel: (01208) 893407 Dolcoath Avenue www.ncdc.gov.uk Camborne · TR14 8SX Tel: (01209) 614000 CARADON www.kerrier.gov.uk Environmental Services (animals) CARRICK Caradon District Council Lost Dogs - Luxstowe House Dog Warden Service Liskeard · PL14 3DZ Carrick District Council Tel: (01579) 345439 Carrick House www.caradon.gov.uk Pydar Street Truro · TR1 1EB RESTORMEL Tel: (01872) 224400 Lost Dogs www.carrick.gov.uk Tregongeeves St Austell · PL26 7DS PENWITH Tel: (01726) 223311 Dog Watch and www.restormel.gov.uk Welfare Officer Penwith District Council St Clare Penzance · TR18 3QW Tel: (01736) 336616 www.penwith.gov.uk Further Information If you would like further information on Cornwall and dog friendly establishments please contact VisitCornwall on (01872) 322900 or e-mail [email protected] alternatively visit www.visitcornwall.com Welcome to the Cornwall Visitor Guide for Dog Welfare Dog Owners, here to help you explore Cornwall’s beaches, gardens and attractions with all the Please remember that in hot weather beaches may not be family including four legged members. -

First Penzance

First Penzance - Sheffield CornwallbyKernow 5 via Newlyn - Gwavas Saturdays Ref.No.: PEN Service No A1 5 5 A1 5 5 A1 5 A1 A1 A1 M6 M6 M6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Penzance bus & rail station 0835 0920 1020 1035 1120 1220 1235 1320 1435 1635 1740 1920 2120 2330 Penzance Green Market 0838 0923 1023 1038 1123 1223 1238 1323 1438 1638 1743 1923 2123 2333 Penzance Alexandra Inn 0842 - - 1042 - - 1242 - 1442 1642 1747 1926 2126 2336 Alverton The Ropewalk - 0926 1026 - 1126 1226 - - - - - - - - Lansdowne Estate Boswergy - - - - - - - 1327 - - - - - - Newlyn Coombe - - - - - - - 1331 - - - - - - Newlyn Bridge 0846 0930 1030 1046 1130 1230 1246 1333 1446 1646 1751 1930 2130 2340 Gwavas Chywoone Roundabout - 0934 1034 - 1134 1234 - 1337 - - - 1951 2151 0001 Gwavas Chywoone Crescent - - - - - 1235 - 1338 - - - 1952 2152 0002 Gwavas Chywoone Avenue Roundabout - 0937 1037 - 1137 1237 - 1340 - - 1755 1952 2152 0002 Gwavas crossroads Chywoone Hill 0849 - - 1049 - - 1249 - 1449 1649 1759 - - - Lower Sheffield - 0941 1041 - 1141 1241 - 1344 - - - - - - Sheffield 0852 - - 1052 - - 1252 - 1452 1652 1802 1955 2155 0005 Paul Boslandew Hill - 0944 1044 - 1144 1244 - 1347 - - - 1958 2158 0008 ! - Refer to respective full timetable for full journey details Service No A1 5 A1 5 5 A1 5 5 A1 A1 A1 A1 M6 M6 M6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sheffield 0754 - 1025 - - 1225 - - 1425 1625 1825 1925 1955 2155 0005 Lower Sheffield - 0941 - 1041 1141 - 1241 1344 - - - - 1955 2155 0005 Paul Boslandew Hill 0757 0944 - 1044 1144 - 1244 1347 - - - - 1958 2158 0008 Gwavas crossroads Chywoone Avenue -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

405 Pedna Carne to Bodmin 408 Summercourt to St Mawgan Via St

405 408 405 Pedna Carne to Bodmin 408 Summercourt to St Mawgan via St. Columb Major via Newquay Airport Mondays to Fridays except bank holidays Mondays to Fridays except bank holidays towards Bodmin towards Penda Carne towards St Mawgan towards Morrisons Pedna Carne Caravan Park 0925 Bodmin Sainsburys 1330 Summercourt Bus Garage 0750 Newquay Airport TR Kingsley Village Fraddon Services 0930 Bodmin ASDA 1335 Summercourt Beacon Road 0751 St Mawgan Village School 1520 Fraddon Westbourne Terrace 0933 Bodmin Morrisons 1340 Gummows Shop 0752 Trenance 1530 Indian Queens Tregawne 0936 Bodmin Mount Folly 1346 Dairyland 0753 Mawgan Porth 1535 St Columb Road Co-op 0938 Bodmin Community Hospital 1353 Quintrell Downs 0800 Tregurrian 1540 172 St Columb Major Trelawney Parc 0946 Nanstallon School 1358 Hendra Holiday Park 0804 Watergate Bay 1542 St Columb Major Old Cattle Market 0948 Ruthernbridge 1404 Morrisons Treloggan Road 0805 Porth Beach 1545 Winnards Perch Birds Of Prey 0954 Withiel Opp St Clements Church 1410 Marcus Hill One stop Shop 0812 Porth Four Turns 1547 Rosenannon 1001 St Wenn School Car Park 1417 Post Office East Street 0813 Burger King 1550 Hag-Gla Cottage 1006 Hag-Gla Cottage 1419 Great Western Hotel 0814 Marcus Hill One stop Shop R St Wenn School Car Park 1008 Rosenannon 1424 Tretherras School 0818 Post Office East Street R Withiel St Clements Church 1015 Winnards Perch Birds Of Prey 1430 Porth Beach 0820 Morrisons Treloggan Road 1555 Ruthernbridge 1021 St Columb Major Old Cattle Market 1437 Watergate Bay 0824 Nanstallon opp School -

9 Waves, Tregurrian Hill, Watergate Bay, TR8 4AY, CORNWALL

This access statement does not contain personal opinions as to our suitability for those with access needs, but aims to accurately describe the facilities and services that we offer all our guests/visitors. Access Statement for “9 Waves” 9 Waves, Tregurrian Hill, Watergate Bay, TR8 4AY, CORNWALL Introduction 9 Waves is a contemporary 1-bedroom apartment that sleeps up to 4 people and is located within the popular Waves development at Watergate Bay in Cornwall. The property has a private terrace and overlooks the garden in the back. The beach and nearest restaurants are within 100m walking distance down the hill. For bookings please contact Beach Retreats on 01637 861 005 or visit www.beachretreats.co.uk. Pre-arrival Information The nearest train station is Newquay 3 miles (15 min drive) south from Watergate Bay. Nearest Airport - Newquay Cornwall Airport (NQY) is located 2 miles (5 min drive) north from Watergate Bay. Local bus route 556 runs regular services between Newquay, Watergate Bay, Newquay Airport and Padstow. (For bus times and fares please visit http://www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/devon_cornwall/journey_planning/). The bus stop is right outside the apartment building. Taxis are available at Newquay train station or can be ordered at the airport on arrival. For pre-booking a taxi we recommend Trenance Cars, tel 01637 262626. Accessible taxis are available on request from A2B taxi, tel 01872 272989. The nearest mobility shop, Independent Living, can be found in Newquay, address 3 St George’s Road, Newquay TR7 1RE. Tel 01637 498015. They also provide equipment hire. Arrival, Parking and Key Collection The apartments are located in the centre of Watergate Bay. -

Cornwall Network Map Summer 2021.Pdf

Harlyn Bay Pityme St Kew St Tudy Highway Trevone Rock Wenfordbridge Harlyn Constantine Bay Padstow Constantine Bay Tesco St Mabyn St Merryn Whitecross Wadebridge Porthcothan Bay St Issey Treburrick Washaway 9 A3 Bedruthan Steps Bodmin 27 St Eval Bodmin Jail Trenance Ruthernbridge Morrisons Mawgan Porth Nanstallon Trevarrian Winnard’s S2 Perch Bodmin & Wenford Steam Railway S1 S2 S3 Watergate Bay Tregurrian Lanivet Tregonetha 86 87 91 Watergate Bay RAF St Mawgan Lanhydrock St Columb 0 Major A3 Newquay S3 St Columb Cornwall Services Minor Victoria Fistral Beach Pentire Head Quintrell White Porth Downs Cross Roche Crantock Treloggan Bugle Lanlivery St Columb Indian Holywell Bay Road Queens Kestle Mill Dairyland Whitemoor St Dennis Luxulyan 86 Fraddon Holywell 87 eves 87 days Trerice Stenalees see Daytripper for details Cubert of all buses to Eden Project S1 Treviscoe Nanpean Penwithick Eden St Blazey Rejerrah St Newlyn Summercourt Project East Tywardreath Perran Foxhole Perranporth Beach Castle Sands 0 D5 A3 Carclaze Par Dore Perranporth Mitchell St Austell Goonhavern St Stephen D5 24 27 Biscovey 24 Cocks 9 Charlestown St Mewan Asda Zelah A3 Fowey Grampound Treloweth Trevellas Road Perrnazabuloe Tregorrick Trispen Ladock Hewas Water Sticker Penhallow St Erme 90 A3 London St Agnes Apprentice Allet Probus Grampound 87 86 0 A3 Pentewan Porthtowan Beach Shortlanesend Mount Tresillian A390 The Lost Gardens Porthtowan Hawke Royal Cornwall of Heligan Chiverton Hospital H A390 Tregony Mevagissey Portreath Beach Bridge 24 Portreath Chacewater Truro -

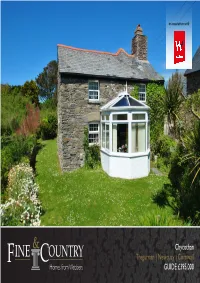

Chycothan Tregurrian | Newquay | Cornwall GUIDE £395 ,000

in association with Chycothan Tregurrian | Newquay | Cornwall GUIDE £395 ,000 CHYCOTHAN TREGURRIAN · NEWQUAY· CORNWALL · TR8 4AD A charming detached character cottage located in the hamlet of Tregurrian, less than half a mile from the beach at popular Watergate Bay and a similar distance from Mawgan Porth. 2 reception rooms, conservatory, kitchen and utility room. 4 first floor bedrooms of a good size, bathroom/wc & shower room/wc • Charming 4 bed detached character cottage • 21ft long master bedroom with vaulted ceiling • Less than half a mile from the beach at Watergate Bay • Oil fired central heating and double glazing • 2 reception rooms, kitchen and a conservatory • Just 4 miles from Newquay & 17 miles from Truro DESCRIPTION The UPVC double glazed conservatory overlooks the well kept Chycothan is a well presented cottage which stands just half a front garden. The garden extends around one side and to the mile from the coast at Watergate Bay between the popular rear where there is a pleasant decked sitting area that enjoys a resort of Newquay and the pretty fishing village of Padstow. distant view down to the sea. The cottage forms part of Tregurrian just 4 miles from Newquay Almost all of the windows are UPVC double glazed (triple glazed and 10 miles from Padstow. The interior is full of traditional in places) and the cottage has an oil fired central heating system, charm and character and there is more accommodation than one the boiler being housed in the downstairs utility room. might expect in the cottage which appears to be one of the oldest in the small hamlet. -

January 2021 Master

to Hartland Welcome Cross Morwenstow Crimp 217 Kilkhampton Coombe Thurdon (school days only) 218 Stibb 218 Poughill 218 217 Bush Grimscott Bude Sea Pool Bude Red Post Stratton Upton Holsworthy Marhamchurch Wednesday only 217 Pyworthy Widemouth Bay Bridgerule Titson Coppathorne Friday only Treskinnick Cross Whitstone Week St Mary North Tamerton Crackington Haven Wainhouse Crackington Corner Monday & Thursday only Broad Boyton Tresparrett Langdon Bennacott Posts Canworthy Water Warbstow Boscastle Langdon North Trevalga Petherwin Trethevy St Nectan's Glen Tintagel Castle Bossiney Yeolmbridge Hallworthy Tintagel Egloskerry Davidstow St Stephen Camelford Trewarmett Station Launceston Castle Pipers Pool Launceston Delabole Valley Polyphant Truckle Camelford Altarnun South Helstone Petherwin Port Isaac St Teath Fivelanes Pendoggett Polzeath St Endellion Bodmin Moor Congdon’s Shop Treburley Trelill 236 Trebetherick St Minver Bolventor Pityme St Tudy St Kew Bray Shop Stoke Climsland Padstow Rock Highway Bathpool Harlyn 236 Tavistock Bodmin Moor Rilla Mill 12 12A Linkinhorne Downgate St Mabyn Constantine Upton Cross St Ann's Gunnislake Kelly Bray Chapel St Issey Whitecross Porthcothan Pensilva Bedruthan Steps Wadebridge Callington Harrowbarrow Treburrick Ashton Calstock Bodmin River Tamar Carnewas Tremar 12A St Dominick St Neot St Cleer St Eval 12 Trenance St Ive Ruthernbridge Liskeard Merrymeet St Mellion Mawgan Porth Rosenannon Winnard’s Doublebois Trevarrian St Mawgan Perch River Tamar Tregurrian Lanivet Bodmin East Taphouse Parkway Menheniot -

BIC-1960.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preamble ... ... ... ... ... ... 3 Obituary—Lt.-Col. B. H. Ryves ... ... ... ... 6 List of Contributors ... ... ... ... ... 7 Cornish Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 9 Arrival and Departure Tables ... ... ... ... 42 The Isles of Scilly ... ... ... ... ... 47 Arrival and Departure of Migrants in the Isles of Scilly ... 55 The Breeding Habits of the Corn-Bunting ... ... 57 Supplementary Notes on the Breeding Habits of the Corn- Bunting ... ... ... ... ... ... 77 Our Society and the Protection of Birds Act ... ... 86 Wildfowl Counts in Cornwall ... ... ... ... 87 Melancoose Reservoir, Newquay ... ... ... ... 88 Bird Notes from the Bishop Rock Lighthouse ... ... 89 Survey of Whinchat and Stonechat ... ... ... 95 Forest Types and Common Forest Birds in West Cornwall ... 97 The Macmillan Library ... ... ... ... ... 104 The Society's Rules ... ... ... ... ... 106 Balance Sheet ... ... ... ... ... ... 107 List of Members ... ... ... ... ... 108 Committees for 1960 and 1961 ... ... ... ... 122 Index 123 THIRTIETH REPORT OF The Cornwall Bird-Watching and Preservation Society 1960 Edited by J. E. BECKERLEGGE & G. ALLSOP (kindly assisted by H. M. QUICK, R. H. BLAIR & A. G. PARSONS) The Society Membership now exceeds seven hundred; during the year, forty have joined the Society, but losses by death and resigna tion were fourteen. On February 6th a meeting was held at the Museum in Truro, at which a talk on " Bird recognition in the field," by Mr. Parsons, was followed by a discussion. The twenty-ninth Annual General Meeting was held in Truro on April 23rd under the chairmanship of Dr. Blair. At this meeting Sir Edward Bolitho, Dr. Blair, Mr. Martyn, Col. Ryves, the Rev. J. E. Beckerlegge and Dr. Allsop were re-elected as President, Chair man, Treasurer and Secretaries, respectively. -

The County of Cornwall (Restormel) (Rural Settlements) (Various Streets) (On-Street Parking Places and Restrictions on Waiting) (Consolidation) Order 2010

The County of Cornwall (Restormel) (Rural Settlements) (Various Streets) (On-Street Parking Places and Restrictions on Waiting) (Consolidation) Order 2010 THE CORNWALL COUNCIL in exercise of its powers under Sections 1, 2, 32 and 35 (and Part IV of Schedule 9) to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (hereinafter referred to as “the Act of 1984”) and of all other enabling powers, and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act of 1984, hereby make the following Order:- 1 Commencement, Citation and Revocation 1.1 This Order shall come into operation on the 6th day of May 2010 and may be cited as “The County of Cornwall (Restormel) (Rural Settlements) (Various Streets) (On-Street Parking Places and Restrictions on Waiting) (Consolidation) Order 2010” 1.2 The Traffic Regulation Orders specified in Article 8 to this Order are hereby revoked and their provisions are consolidated in this Order. 2 Interpretations 2.1 In this Order, except where the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the meanings hereby respectively assigned to them:- 2.1.1 “badges regulations” means the Disabled Persons (badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000; 2.1.2 “disabled person’s badge” has the same meaning as in the Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000; 2.1.3 “disabled person’s parking place” means any area of highway described in the Fourteenth Schedule to this Order which is comprised within and indicated by a road marking complying with