Olympian Omnipotence Versus Karmic Adjustment in Pynchon's Vineland David Rando Trinity University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

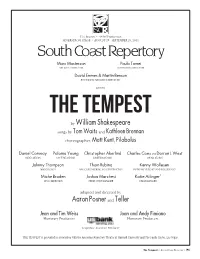

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Sundance Institute Announces Casts for Summer Theatre Laboratory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: June 21, 2006 Irene Cho [email protected], 801.328.3456 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES CASTS FOR SUMMER THEATRE LABORATORY AWARD-WINNING ACTORS ANTHONY RAPP, RAÚL ESPARZA AND OTHERS TO WORKSHOP SEVEN NEW PLAYS AT JULY LAB IN UTAH Salt Lake City, UT – Today, Sundance Institute announced the acting ensemble for the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory, to be held July 10-30, 2006 at the Sundance Resort in Utah. The company includes: Bradford Anderson, Nancy Anderson, Whitney Bashor, Judy Blazer, Reg E. Cathey, Will Chase, Johanna Day, Raúl Esparza, Jordan Gelber, Kimberly Hebert Gregory, Carla Harting, Roderick Hill, Nicholas Hormann, Christina Kirk, Ezra Knight, Judy Kuhn, Anika Larsen, Piter Marek, Kelly McCreary, Chris Messina, Jennifer Mudge, Novella Nelson, Toi Perkins, Anthony Rapp, Gareth Saxe, Tregoney Shepherd, Michael Stuhlbarg and Price Waldman. The seven plays to be developed at the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory include: CITIZEN JOSH, by Josh Kornbluth, directed by David Dower, an improvisational solo show which strives to rescue “democracy” from the sloganeers in a personal autobiographical format; CURRENT NOBODY, by Melissa James Gibson, directed by Daniel Aukin, a modern reinterpretation of Homer’s The Odyssey; GEOMETRY OF FIRE, by Stephen Belber, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, which weaves the story of an American reservist just back from Iraq and a Saudi-American citizen investigating his father’s death; THE EVILDOERS, by David Adjmi, directed by Rebecca Taichman, a play in which the marriage of two couples unravel in a dark yet comedic context; …AND JESUS MOONWALKS THE MISSISSIPPI, by Marcus Gardley, directed by Matt August, a poetic retelling of the Demeter myth set during the Civil War; KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, book by Robert L. -

The Rhythm of the Gods' Voice. the Suggestion of Divine Presence

T he Rhythm of the Gods’ Voice. The Suggestion of Divine Presence through Prosody* E l ritmo de la voz de los dioses. La sugerencia de la presencia divina a través de la prosodia Ronald Blankenborg Radboud University Nijmegen [email protected] Abstract Resumen I n this article, I draw attention to the E ste estudio se centra en la meticulosidad gods’ pickiness in the audible flow of de los dioses en el flujo audible de sus expre- their utterances, a prosodic characteris- siones, una característica prosódica del habla tic of speech that evokes the presence of que evoca la presencia divina. La poesía hexa- the divine. Hexametric poetry itself is the métrica es en sí misma el lenguaje de la per- * I want to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of ARYS for their suggestions and com- ments. https://doi.org/10.20318/arys.2020.5310 - Arys, 18, 2020 [123-154] issn 1575-166x 124 Ronald Blankenborg language of permanency, as evidenced by manencia, como pone de manifiesto la litera- wisdom literature, funereal and dedicatory tura sapiencial y las inscripciones funerarias inscriptions: epic poetry is the embedded y dedicatorias: la poesía épica es el lenguaje direct speech of a goddess. Outside hex- directo integrado de una diosa. Más allá de ametric poetry, the gods’ special speech la poesía hexamétrica, el habla especial de los is primarily expressed through prosodic dioses es principalmente expresado mediante means, notably through a shift in rhythmic recursos prosódicos, especialmente a través profile. Such a shift deliberately captures, de un cambio en el perfil rítmico. -

The Odyssey and the Desires of Traditional Narrative

The Odyssey and the Desires of Traditional Narrative David F. Elmer* udk: 82.0-3 Harvard University udk: 821.14-13 [email protected] Original scientific paper Taking its inspiration from Peter Brooks’ discussion of the “narrative desire” that structures novels, this paper seeks to articulate a specific form of narrative desire that would be applicable to traditional oral narratives, the plots of which are generally known in advance by audience members. Thematic and structural features of theOdyssey are discussed as evidence for the dynamics of such a “traditional narrative desire”. Keywords: Narrative desire, Peter Brooks, Odyssey, oral tradition, oral literature In a landmark 1984 essay entitled “Narrative Desire”, Peter Brooks argued that every literary plot is structured in some way by desire.1 In his view, the desires of a plot’s protagonist, whether these are a matter of ambition, greed, lust, or even simply the will to survive, determine the plot’s very readability or intelligibility. Moreover, for Brooks the various desires represented within narrative figure the desires that drive the production and consumption of narrative. He finds within the narrative representation of desire reflections of the desire that compels readers to read on, to keep turning pages, and ultimately of an even more fundamental desire, a “primary human drive” that consists simply in the “need to tell” (Brooks 1984, 61). The “reading of plot,” he writes, is “a form of desire that carries us forward, onward, through the text” (Brooks 1984, 37). When he speaks of “plot”, Brooks has in mind a particular literary form: the novel, especially as exemplified by 19th-century French realists like Honoré de Balzac and Émile Zola. -

Odysseus and Feminine Mêtis in the Odyssey Grace Lafrentz

Vanderbilt Undergraduate Research Journal, Vol. 11 Weaving a Way to Nostos: Odysseus and Feminine Mêtis in the Odyssey Grace LaFrentz Abstract. My paper examines the gendered nature of Odysseus’ mêtis, a Greek word describing characteristics of cleverness and intelligence, in Homer’s Odyssey. While Odysseus’ mêtis has been discussed in terms of his storytelling, disguise, and craftsmanship, I contend that in order to fully understand his cleverness, we must place Odysseus’ mêtis in conversation with the mêtis of the crafty women who populate the epic. I discuss weaving as a stereotypically feminine manifestation of mêtis, arguing that Odysseus’ reintegration into his home serves as a metaphorical form of weaving—one that he adapts from the clever women he encounters on his journey home from Troy. Athena serves as the starting point for my discussion of mêtis, and I then turn to Calypso and Circe—two crafty weavers who attempt to ensnare Odysseus on their islands. I also examine Helen, whom Odysseus himself does not meet, but whose weaving is importantly witnessed by Odysseus’ son Telemachus, who later draws upon the craft of weaving in his efforts to help Odysseus restore order in his home. The last woman I present is Penelope, whose clever and prolonged weaving scheme helps her evade marriage as she awaits Odysseus’ return, and whose lead Odysseus follows in his own prolonged reentry into his home. I finally demonstrate the way that Odysseus reintegrates himself into his household through a calculated and metaphorical act of weaving, arguing that it is Odysseus’ willingness to embrace a more feminine model of mêtis embodied by the women he encounters that sets him apart from his fellow male warriors and enables his successful homecoming. -

23 Hero-Without-Nostos.Pdf

1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Int class trad DOI 10.1007/s12138-014-0367-6 ARTICLE A Hero Without Nostos: Ulysses’ Last Voyage in Twentieth-Century Italy Francesca Schironi © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2015 Abstract The article reviews the reception of Ulysses’ last voyage in twentieth- century Italy. Ulysses’ last voyage is used by Italian authors to discuss different and often opposing views of the ideal human life as well as the intellectual and exis- tential angsts of the twentieth century. In addition, the Italian twentieth-century Ulysses becomes part of a metapoetic discourse, as going back to the Homeric and Dantesque myths of Ulysses for an artist also means interrogating oneself on the possibility of creating something new within a long tradition. This metaliterary dimension adds to the modern Italian reception of Ulysses, making it a unique case of the intersection of many different layers of reception both in chronological and thematic terms. -

Françoise Létoublon We Shall Here Study the Possible Coherence Or

Brolly. Journal of Social Sciences 1 (2) 2018 LIVING IN IRON, DRESSED IN BRONZE: METAL FORMULAS AND THE CHRONOLOGY OF AGES1 Françoise Létoublon UFR LLASIC University Grenoble-Alpes, France [email protected] Abstract. Names of important metals such as gold, silver, iron, and bronze occur many times in the Homeric Epics. We intend to look at them within the framework of oral poetry, with the purpose to determine if they form a more or less coherent set of “formulas”, in the sense defined by Milman Parry and the Oral Poetry Theory2, and to test a possible link with the stages of the evolution of humankind. Though several specialists criticized some excess in Parry’s and Lord’s definitions of the formula, we deem the theory still valuable in its great lines and feel no need to discuss it for the present study3. The frequent use of bronze in epical formulas for arms, while the actual heroes fight their battles with iron equipment, and the emphasis of gold in the descriptions of wealth may reflect a deep-seated linguistic memory within the archaic mindset of the Ages of Mankind. With Homer’s language as our best witness, metal formulas testify to the importance of the tradition of the Ages of Mankind in understanding the thought patterns and value-systems, as well as some linguistic usages of the Homeric Epics. Keywords: oral poetry, the Myth of Ages, metals, gold, bronze, iron, metaphors, anthropology We shall here study the possible coherence or opposition between linguistic and literary artefacts in Homer and Hesiod on one hand, and archaeological or historical data on the other. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `Dangerous Creatures': Selected children's versions of Homer's Odyssey in English 16992014 RICHARDS, FRANCESCA,MARIA How to cite: RICHARDS, FRANCESCA,MARIA (2016) `Dangerous Creatures': Selected children's versions of Homer's Odyssey in English 16992014 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11522/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘Dangerous Creatures’: Selected children’s versions of Homer’s Odyssey in English 1699–2014 Abstract This thesis considers how the Odyssey was adapted for children, as a specific readership, in English literature 1699-2014. It thus traces both the emergence of children’s literature as a publishing category and the transformation of the Odyssey into a tale of adventure – a perception of the Odyssey which is still widely accepted today (and not only among children) but which is not, for example, how Aristotle understood the poem. -

Odysseus's Nostos and the Odyssey's Nostoi

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Odysseus’s nostos and the Odyssey’s nostoi: rivalry within the epic cycle Journal Item How to cite: Barker, Elton T. E. and Christensen, Joel P. (2016). Odysseus’s nostos and the Odyssey’s nostoi: rivalry within the epic cycle. Philologia Antiqua, 7 pp. 85–110. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2014 Not known https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.libraweb.net/articoli3.php?chiave=201404601&rivista=46&articolo=201404601005 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk TO BE RETURNED SIGNED ALONG WITH THE CORRECTED PROOFS Dear Author, We are pleased to send you the first draft of your article that will appear in the next issue of the «Philologia Antiqua» Regarding proofreading (to give back by September 21, 2015), to allow us to proceed with the publication of this article please observe the following: a - Only correct any typos, without changing in any way the original text you sent us; any extra 'author's corrections' (frequent and significant additions, deletions and substitutions) will be charged according to current costs. b - Pay attention to references to the notes, which are normally numbered by page. c - You can send us the corrected draft in the following ways: - Scan the corrected draft and email to: [email protected] - Email a list of corrections (if no more than ten) to: [email protected] d - When the issue comes out you will receive a pdf file of the offprint of your article. -

The Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School

The Haberdashers’ Aske’s Boys’ School Occasional Papers Series in the Humanities Occasional Paper Number Forty Persephone’s Odyssey: Nature and the Supernatural in the Odyssey and Homeric Hymn 2 A.C. Gray [email protected] November 2020 1 A Haberdashers’ Aske’s Occasional Paper. All rights reserved. Haberdashers’ Aske’s Occasional Paper Number Forty November 2020 All rights reserved Persephone’s Odyssey Nature and the Supernatural in the Odyssey and Homeric Hymn 2 A.C. Gray Abstract Although Homeric Hymn 2 (Εἲς Δημήτραν) is not often read for its similarities to the Odyssey, it is impossible to deny that the two poems have myriad details in common. In this paper, I consider one fairly complex axis for comparison: the poems share a similar view of death, the natural world, and the supernatural. This interrelationship provides one way to examine archaic Greek religion in the pre-philosophic era, proposing patterns that may have been consistent in early Greek thought regarding the danger of divine elements in nature, the dead and consumption in the underworld, and morality and “evil” among the gods. The unifying thread is the interaction between human beings and the supernatural, that is to say, natural elements that go above and beyond their ordinary capabilities. 1. Introduction Most people are familiar with the story of the Odyssey, at least, in the broadest strokes. Odysseus is a Greek soldier (from Ithaca) who took part in the Trojan War as described in Homer's Iliad. He spends many years trying to get home following the end of the war, continually thwarted by the god Poseidon, who nurses a grudge against him. -

Literary Elements and Language Terms: Greek Epics

Welcome Back! **Please make a note on your calendar, the reading homework for January 10 should be Books 11 AND 16. Literary Elements and Language Terms: Greek Epics English II Pre-AP THE OLYMPIANS AND THEIR ROLE IN HOMER’S ILIAD THE OLYMPIANS 1. Zeus (Jupiter) 8. Hermes (Mercury) 2. Hera (Juno) 9. Artemis (Diana) 3. Demeter (Ceres) 10. Ares (Mars) 4. Hades (Pluto) 11. Pallas Athena (Minerva) 5. Hestia (Vesta) 12. Hephaestus (Vulcan) 6. Poseidon (Neptune) 13. Aphrodite (Venus) 7. Phoebus Apollo THE ROLE OF THE GODS… Ancient Greece was a polytheistic culture versus today’s more monotheistic culture. The Greeks see the gods as: Awe-inspiring Dangerous Powerful beings whom it is wise not to offend Homer uses the gods to underscore the tragedy of the human condition. Often in the Iliad, the gods and goddesses are portrayed as shallow, petty, etc. They complain, and fight amongst themselves. They watch the war, and may even get involved in points, but they can’t be seriously hurt by this war. This highlights the tragedy of human courage and self sacrifice that will happen throughout the course of the epic. THE HOMERIC GODS ARE NOT… consistently good, or merciful, or even just omniscient (all-seeing) omnipotent (all-powerful) transcendent – they did not create the universe, but are part of it in relationships with humans which are based on mutual love able to override fate THE HOMERIC GODS ARE… personified forces of nature on the most basic level (Ex: Ares is war) the controllers of these forces of nature anthropomorphic – they share human form, human passions, and human emotions THE GODS AND FATE (MOIRA)… Moira roughly translates as “share of life” Generally, a human does not know their moira ahead of time The gods seems to know the individual’s moira (Ex: Thetis knows Achilles’ fate, Zeus knows Achilles will kill Hector) However, the gods are part of the system. -

The Return of Ulysses ‘Only Edith Hall Could Have Written This Richly Engaging and Distinctive Book

the return of ulysses ‘Only Edith Hall could have written this richly engaging and distinctive book. She covers a breathtaking range of material, from the highest of high culture to the camp, cartoonish, and frankly weird; from Europe to the USA to Africa and the Far East; and from literature to film and opera. Throughout this tour of the huge variety of responses that there have been to the Odyssey, a powerful argument emerges about the appeal and longevity of the text which reveals all the critical and political flair that we have come to expect of this author. It is all conveyed with the infectious excitement and clarity of a brilliant performer. The Return of Ulysses represents a major contribution to how we assess the continuing influence of Homer in modern culture.’ — Simon Goldhill, Professor of Greek Literature and Culture, University of Cambridge ‘Edith Hall has written a book many have long been waiting for, a smart, sophisticated, and hugely entertaining cultural history of Homer’s Odyssey spanning nearly three millennia of its reception and influence within world culture. A marvel of collection, association, and analysis, the book yields new discoveries on every page. In no other treatment of the enduring figure of Odysseus does Dante rub shoulders with Dr Who, Adorno and Bakhtin with John Ford and Clint Eastwood. Hall is superb at digging into the depths of the Odyssean character to find what makes the polytropic Greek so internationally indestructible. A great delight to read, the book is lucid, appealingly written, fast, funny, and full of enlightening details.