23 Hero-Without-Nostos.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humour of Homer

The Humour of Homer Samuel Butler A lecture delivered at the Working Men's College, Great Ormond Street 30th January, 1892 The first of the two great poems commonly ascribed to Homer is called the Iliad|a title which we may be sure was not given it by the author. It professes to treat of a quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles that broke out while the Greeks were besieging the city of Troy, and it does, indeed, deal largely with the consequences of this quarrel; whether, however, the ostensible subject did not conceal another that was nearer the poet's heart| I mean the last days, death, and burial of Hector|is a point that I cannot determine. Nor yet can I determine how much of the Iliadas we now have it is by Homer, and how much by a later writer or writers. This is a very vexed question, but I myself believe the Iliadto be entirely by a single poet. The second poem commonly ascribed to the same author is called the Odyssey. It deals with the adventures of Ulysses during his ten years of wandering after Troy had fallen. These two works have of late years been believed to be by different authors. The Iliadis now generally held to be the older work by some one or two hundred years. The leading ideas of the Iliadare love, war, and plunder, though this last is less insisted on than the other two. The key-note is struck with a woman's charms, and a quarrel among men for their possession. -

Sample Odyssey Passage

The Odyssey of Homer Translated from Greek into English prose in 1879 by S.H. Butcher and Andrew Lang. Book I In a Council of the Gods, Poseidon absent, Pallas procureth an order for the restitution of Odysseus; and appearing to his son Telemachus, in human shape, adviseth him to complain of the Wooers before the Council of the people, and then go to Pylos and Sparta to inquire about his father. Tell me, Muse, of that man, so ready at need, who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy, and many were the men whose towns he saw and whose mind he learnt, yea, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep, striving to win his own life and the return of his company. Nay, but even so he saved not his company, though he desired it sore. For through the blindness of their own hearts they perished, fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios Hyperion: but the god took from them their day of returning. Of these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, whencesoever thou hast heard thereof, declare thou even unto us. Now all the rest, as many as fled from sheer destruction, were at home, and had escaped both war and sea, but Odysseus only, craving for his wife and for his homeward path, the lady nymph Calypso held, that fair goddess, in her hollow caves, longing to have him for her lord. But when now the year had come in the courses of the seasons, wherein the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaca, not even there was he quit of labours, not even among his own; but all the gods had pity on him save Poseidon, who raged continually against godlike Odysseus, till he came to his own country. -

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

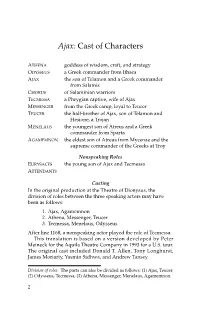

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

The Rhythm of the Gods' Voice. the Suggestion of Divine Presence

T he Rhythm of the Gods’ Voice. The Suggestion of Divine Presence through Prosody* E l ritmo de la voz de los dioses. La sugerencia de la presencia divina a través de la prosodia Ronald Blankenborg Radboud University Nijmegen [email protected] Abstract Resumen I n this article, I draw attention to the E ste estudio se centra en la meticulosidad gods’ pickiness in the audible flow of de los dioses en el flujo audible de sus expre- their utterances, a prosodic characteris- siones, una característica prosódica del habla tic of speech that evokes the presence of que evoca la presencia divina. La poesía hexa- the divine. Hexametric poetry itself is the métrica es en sí misma el lenguaje de la per- * I want to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of ARYS for their suggestions and com- ments. https://doi.org/10.20318/arys.2020.5310 - Arys, 18, 2020 [123-154] issn 1575-166x 124 Ronald Blankenborg language of permanency, as evidenced by manencia, como pone de manifiesto la litera- wisdom literature, funereal and dedicatory tura sapiencial y las inscripciones funerarias inscriptions: epic poetry is the embedded y dedicatorias: la poesía épica es el lenguaje direct speech of a goddess. Outside hex- directo integrado de una diosa. Más allá de ametric poetry, the gods’ special speech la poesía hexamétrica, el habla especial de los is primarily expressed through prosodic dioses es principalmente expresado mediante means, notably through a shift in rhythmic recursos prosódicos, especialmente a través profile. Such a shift deliberately captures, de un cambio en el perfil rítmico. -

A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate Style Answers

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL Candidate style answers CLASSICAL CIVILISATION H408 For first assessment in 2019 H408/11: Homer’s Odyssey Version 1 www.ocr.org.uk/alevelclassicalcivilisation A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate style answers Contents Introduction 3 Question 3 4 Question 4 8 Essay question 12 2 © OCR 2019 A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate style answers Introduction OCR has produced this resource to support teachers in interpreting the assessment criteria for the new A Level Classical Civilisation specification and to bridge the gap between new specification’s release and the availability of exemplar candidate work following first examination in summer 2019. The questions in this resource have been taken from the H408/11 World of the Hero specimen question paper, which is available on the OCR website. The answers in this resource have been written by students in Year 12. They are supported by an examiner commentary. Please note that this resource is provided for advice and guidance only and does not in any way constitute an indication of grade boundaries or endorsed answers. Whilst a senior examiner has provided a possible mark/level for each response, when marking these answers in a live series the mark a response would get depends on the whole process of standardisation, which considers the big picture of the year’s scripts. Therefore the marks/levels awarded here should be considered to be only an estimation of what would be awarded. How levels and marks correspond to grade boundaries depends on the Awarding process that happens after all/most of the scripts are marked and depends on a number of factors, including candidate performance across the board. -

The Odyssey and the Desires of Traditional Narrative

The Odyssey and the Desires of Traditional Narrative David F. Elmer* udk: 82.0-3 Harvard University udk: 821.14-13 [email protected] Original scientific paper Taking its inspiration from Peter Brooks’ discussion of the “narrative desire” that structures novels, this paper seeks to articulate a specific form of narrative desire that would be applicable to traditional oral narratives, the plots of which are generally known in advance by audience members. Thematic and structural features of theOdyssey are discussed as evidence for the dynamics of such a “traditional narrative desire”. Keywords: Narrative desire, Peter Brooks, Odyssey, oral tradition, oral literature In a landmark 1984 essay entitled “Narrative Desire”, Peter Brooks argued that every literary plot is structured in some way by desire.1 In his view, the desires of a plot’s protagonist, whether these are a matter of ambition, greed, lust, or even simply the will to survive, determine the plot’s very readability or intelligibility. Moreover, for Brooks the various desires represented within narrative figure the desires that drive the production and consumption of narrative. He finds within the narrative representation of desire reflections of the desire that compels readers to read on, to keep turning pages, and ultimately of an even more fundamental desire, a “primary human drive” that consists simply in the “need to tell” (Brooks 1984, 61). The “reading of plot,” he writes, is “a form of desire that carries us forward, onward, through the text” (Brooks 1984, 37). When he speaks of “plot”, Brooks has in mind a particular literary form: the novel, especially as exemplified by 19th-century French realists like Honoré de Balzac and Émile Zola. -

Odysseus and Feminine Mêtis in the Odyssey Grace Lafrentz

Vanderbilt Undergraduate Research Journal, Vol. 11 Weaving a Way to Nostos: Odysseus and Feminine Mêtis in the Odyssey Grace LaFrentz Abstract. My paper examines the gendered nature of Odysseus’ mêtis, a Greek word describing characteristics of cleverness and intelligence, in Homer’s Odyssey. While Odysseus’ mêtis has been discussed in terms of his storytelling, disguise, and craftsmanship, I contend that in order to fully understand his cleverness, we must place Odysseus’ mêtis in conversation with the mêtis of the crafty women who populate the epic. I discuss weaving as a stereotypically feminine manifestation of mêtis, arguing that Odysseus’ reintegration into his home serves as a metaphorical form of weaving—one that he adapts from the clever women he encounters on his journey home from Troy. Athena serves as the starting point for my discussion of mêtis, and I then turn to Calypso and Circe—two crafty weavers who attempt to ensnare Odysseus on their islands. I also examine Helen, whom Odysseus himself does not meet, but whose weaving is importantly witnessed by Odysseus’ son Telemachus, who later draws upon the craft of weaving in his efforts to help Odysseus restore order in his home. The last woman I present is Penelope, whose clever and prolonged weaving scheme helps her evade marriage as she awaits Odysseus’ return, and whose lead Odysseus follows in his own prolonged reentry into his home. I finally demonstrate the way that Odysseus reintegrates himself into his household through a calculated and metaphorical act of weaving, arguing that it is Odysseus’ willingness to embrace a more feminine model of mêtis embodied by the women he encounters that sets him apart from his fellow male warriors and enables his successful homecoming. -

The Penelopiad

THE PENELOPIAD Margaret Atwood EDINBURGH • NEW YORK • MELBOURNE For my family ‘… Shrewd Odysseus! … You are a fortunate man to have won a wife of such pre-eminent virtue! How faithful was your flawless Penelope, Icarius’ daughter! How loyally she kept the memory of the husband of her youth! The glory of her virtue will not fade with the years, but the deathless gods themselves will make a beautiful song for mortal ears in honour of the constant Penelope.’ – The Odyssey, Book 24 (191–194) … he took a cable which had seen service on a blue-bowed ship, made one end fast to a high column in the portico, and threw the other over the round-house, high up, so that their feet would not touch the ground. As when long-winged thrushes or doves get entangled in a snare … so the women’s heads were held fast in a row, with nooses round their necks, to bring them to the most pitiable end. For a little while their feet twitched, but not for very long. – The Odyssey, Book 22 (470–473) CONTENTS Introduction i A Low Art ii The Chorus Line: A Rope-Jumping Rhyme iii My Childhood iv The Chorus Line: Kiddie Mourn, A Lament by the Maids v Asphodel vi My Marriage vii The Scar viii The Chorus Line: If I Was a Princess, A Popular Tune ix The Trusted Cackle-Hen x The Chorus Line: The Birth of Telemachus, An Idyll xi Helen Ruins My Life xii Waiting xiii The Chorus Line: The Wily Sea Captain, A Sea Shanty xiv The Suitors Stuff Their Faces xv The Shroud xvi Bad Dreams xvii The Chorus Line: Dreamboats, A Ballad xviii News of Helen xix Yelp of Joy xx Slanderous Gossip xxi The Chorus Line: The Perils of Penelope, A Drama xxii Helen Takes a Bath xxiii Odysseus and Telemachus Snuff the Maids xxiv The Chorus Line: An Anthropology Lecture xxv Heart of Flint xxvi The Chorus Line: The Trial of Odysseus, as Videotaped by the Maids xxvii Home Life in Hades xxviii The Chorus Line: We’re Walking Behind You, A Love Song xxix Envoi Notes Acknowledgements Introduction The story of Odysseus’ return to his home kingdom of Ithaca following an absence of twenty years is best known from Homer’s Odyssey. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

Djebar's Scheherazade & Atwood's Penelope

Mythic women reborn: Djebar's Scheherazade & Atwood's Penelope Item Type Thesis Authors Frentzko, Brianna Nicole Download date 25/09/2021 03:49:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/10563 MYTHIC WOMEN REBORN: DJEBAR'S SCHEHERAZADE & ATWOOD'S PENELOPE By Brianna Nicole Frentzko, M.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2019 © 2019 Brianna Nicole Frentzko APPROVED: Geraldine Brightwell, Committee Co-Chair Eileen Harney, Committee Co-Chair Rich Carr, Committee Member Sara Eliza Johnson, Committee Member Rich Carr, Chair Department of English Todd Sherman, Dean College of Liberal Arts Michael Castellini, Dean Graduate School ABSTRACT This thesis examines how two modern female writers approach the retelling of stories involving mythic heroines. Assia Djebar's A Sister to Scheherazade repurposes Arabian Nights to reclaim a sisterly solidarity rooted in a pre-colonial Algerian female identity rather than merely colonized liberation. In approaching the oppressive harem through the lens of the bond between Scheherazade and her sister Dinarzade, Djebar allows women to transcend superficial competition and find true freedom in each other. Margaret Atwood's The Penelopiad interrogates the idealized wife Penelope from Homer's Odyssey in order to highlight its heroine's complicity in male violence against women. Elevating the disloyal maids whom Odysseus murders, Atwood questions the limitations of sisterhood and the need to provide visibility, voice, and justice for the forgotten victims powerful men have dismissed and destroyed. The two novels signal a shift in feminist philosophy from the need for collective action to the need to recognize individual narratives. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop.